2026-02-17 16:08:40

I have some personal Git repos that I want to sync between my devices – my dotfiles, text expansion macros, terminal colour schemes, and so on.

For a long time, I used GitHub as my sync layer – it’s free, convenient, and I was already using it – but recently I’ve been looking at alternatives. I’m trying to reduce my dependency on cloud services, especially those based in the USA, and I don’t need most of GitHub’s features. I made these repos public, in case somebody else might find them useful, but in practice I think very few people ever looked at them.

There are plenty of GitHub-lookalikes, which are variously self-hosted or hosted outside the USA, like GitLab, Gitea, or Codeberg – but like GitHub, they all have more features than I need. I just care about keeping my files in sync. Maybe I could avoid introducing another service?

As I thought about how Git works, I thought of a much simpler way – and I’m almost embarrassed by how long it took me to figure this out.

In Git repos, there’s a .git folder which holds the complete state of the repo.

It includes the branches, the commits, and the contents of every file.

If you copy that .git folder to a new location, you’d get another copy of the repo.

You could copy a repo with basic utilities like cp or rsync – at least, as a one-off.

I wouldn’t recommend using them for regular syncing; it would be easy to lose data, because they don’t know how to merge changes from different devices.

Git’s built-in push and pull commands are smarter: they can synchronise this state between locations, compare the history of different copies, and stitch the changes together safely.

Within a repo, you can create a remote location, a pointer to another copy of the repo that lives somewhere else.

When you push or pull, your local .git folder gets synchronised with that other copy.

We’ve become used to the idea that the remote location is a cloud service – but it can just as easily be a folder on your local disk – and that gives me everything I want.

Before I explain the steps, I need to explain the difference between bare and non-bare repositories.

In our day-to-day work, we use non-bare repositories.

They have a “working directory” – the files you can see and edit.

The .git folder lives under this directory, and stores the entire history of the repo.

The working directory is a view into a particular point in that history.

By contrast, a bare repository is just the .git folder without the working directory.

It’s the history without the view.

You can’t push changes to a non-bare repo – if you try, Git will reject your push.

This is to avoid confusing situations where the working directory and the .git folder get out of sync.

Imagine if you had the repo open in a text editor, and somebody else pushed new code to the repo – suddenly your files would no longer match the Git history.

Whenever we push, we’re normally pushing to a bare repository. Because nobody can “work” inside a bare repo, it’s always safe to receive pushes from other locations – there’s no working directory to get out of sync.

I have a home desktop which is always running, and it’s connected to a large external drive. For each repo, there’s a bare repository on the external drive, and then all my devices have a checked-out copy that points to the path on that external drive as their remote location. The desktop connects to the drive directly; the other devices connect over SSH.

This only takes a few commands to set up:

Create a bare repository on the external drive.

$ cd /Volumes/Media/bare-repos

$ git init --bare dotfilesSet the bare repository as a remote location.

On the home desktop, which mounts the external drive directly:

$ cd ~/repos/dotfiles

$ git remote add origin /Volumes/Media/bare-repos/dotfilesOn a machine, which can access the drive over SSH:

$ cd ~/repos/dotfiles

$ git remote add origin alexwlchan@desktop:/Volumes/Media/bare-repos/dotfilesThis allows me to run git push and git pull commands as normal, which will copy my history to the bare repository.

Clone the bare repository to a new location.

When I set up a new computer:

$ git clone /Volumes/Media/bare-repos/dotfiles ~/repos/dotfilesThis approach is very flexible, and you can store your bare repository in any location that’s accessible on your local filesystem or SSH. You could use an external drive, a web server, a NAS, whatever. I’m using Tailscale to get SSH access to my repos from other devices, but any mechanism for connecting devices over SSH will do. (Disclaimer: I work at Tailscale.)

Of course, this is missing many features of GitHub and the like – there’s no web interface, no issue tracking, no collaboration – but for my small, personal repos, that’s fine. There’s also no third-party hosting, no risk of outages, no services to manage. I’m just moving files about over the filesystem. It feels like the Git equivalent of static websites, in a good way.

I used to throw every scrap of code onto GitHub in the vague hope of “sharing knowledge”, but most of it was digital clutter.

Nobody was reading my personal repos in the hope of learning something. They’re a grab bag of assorted snippets, with only a loose definition or purpose – it’s unlikely another person would know what they could find, or spend the time to go looking. Sharing knowledge requires more than just publishing code somewhere; you need to make it possible for somebody to find.

Extracting my ideas into standalone, searchable snippets makes them dramatically more useful and discoverable. There are single blog posts that have done more good than my entire corpus of code on GitHub – and I have hundreds of blog posts.

I still have plenty of public repos, but it’s specific libraries or tools with a clear purpose. It’s more obvious whether you might want to read it, and better documented if you do. It’s an intentional selection, not a random set of things I want to keep in sync.

For years, I’ve been using a social media site as a glorified file-syncing service, but I don’t need pull requests, an issue tracker, or a CI/CD pipeline to move a few macros between my machines – just a place to put my code. As with so many digital things, files and folders are all I need.

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]

2026-02-05 16:21:14

I’m currently restructuring my site, and I’m going to change some of the URLs. I don’t want to break inbound links to the old URLs, so I’m creating redirects between old and new.

My current web server is Caddy, so I define redirects in my Caddyfile with the redir directive.

Here’s an example that creates permanent redirects for three URLs:

alexwlchan.net {

redir /videos/crossness_flywheel.mp4 /files/2017/crossness_flywheel.mp4 permanent

redir /2021/12/2021-in-reading/ /2021/2021-in-reading/ permanent

redir /2022/12/print-sbt/ /til/2022/print-sbt/ permanent

}This syntax is easy to write by hand, but it’s annoying if I want to define lots of redirects – and when I’m doing a big restructure, I do. In particular, it’s tricky to write scripts to modify this file.

This is a good use case for Cog, made by Ned Batchelder.

Cog is a tool for running snippets of Python inside text files, allowing you to generate content without external templates or additional files. When you process a file with Cog, it finds those snippets of Python, executes them, then inserts the output back into the original file.

Here’s an example:

alexwlchan.net {

#[[[cog

# import cog

#

# redirects = [

# {"old_url": "/videos/crossness_flywheel.mp4", "new_url": "/files/2017/crossness_flywheel.mp4"},

# {"old_url": "/2021/12/2021-in-reading/", "new_url": "/2021/2021-in-reading/"},

# {"old_url": "/2022/12/print-sbt/", "new_url": "/til/2022/print-sbt/"},

# ]

#

# for r in redirects:

# cog.outl(f"redir {r['old_url']} {r['new_url']} permanent")

#]]]

#[[[end]]]

}All the Python code that Cog runs is inside a comment, so it will be ignored by Caddy.

The [[[cog …]]] and [[[end]]] markers tell Cog where to find the code, and it’s smart enough to remove the leading whitespace and comment markers.

When I process this file with Cog (pip install cogapp; cog Caddyfile), it runs the Python snippet, and anything passed to cog.outl() is written between the markers.

This is the output, which gets printed to stdout:

alexwlchan.net {

#[[[cog

# import cog

#

# redirects = [

# {"old_url": "/videos/crossness_flywheel.mp4", "new_url": "/files/2017/crossness_flywheel.mp4"},

# {"old_url": "/2021/12/2021-in-reading/", "new_url": "/2021/2021-in-reading/"},

# {"old_url": "/2022/12/print-sbt/", "new_url": "/til/2022/print-sbt/"},

# ]

#

# for r in redirects:

# cog.outl(f"redir {r['old_url']} {r['new_url']} permanent")

#]]]

redir /videos/crossness_flywheel.mp4 /files/2017/crossness_flywheel.mp4 permanent

redir /2021/12/2021-in-reading/ /2021/2021-in-reading/ permanent

redir /2022/12/print-sbt/ /til/2022/print-sbt/ permanent

#[[[end]]]

}If I want to write the output back to the file, I run Cog with the -r flag (cog -r Caddyfile).

All the original Cog code is preserved, so I can run it again and again to regenerate the file.

This means that if I want to add a new redirect, I can edit the list and run Cog again.

Cog is running a full version of Python, so I can rewrite the snippet to read the list of redirects from an external file. Here’s another example:

alexwlchan.net {

#[[[cog

# import cog

# import json

#

# with open("redirects.json") as in_file:

# redirects = json.load(in_file)

#

# for r in redirects:

# cog.outl(f"redir {r['old_url']} {r['new_url']} permanent")

#]]]

redir /videos/crossness_flywheel.mp4 /files/2017/crossness_flywheel.mp4 permanent

redir /2021/12/2021-in-reading/ /2021/2021-in-reading/ permanent

redir /2022/12/print-sbt/ /til/2022/print-sbt/ permanent

#[[[end]]]

}This is a powerful change – unlike the original Caddyfile, it’s easy to write scripts that insert entries in this external JSON file, and now I can programatically update this file.

My scripts that are rearranging my URLs can populate redirects.json, then I only need to re-run Cog and I have a complete set of redirects in my Caddyfile.

I usually run Cog with two flags:

-r writes the output back to the original file, and-c adds a checksum to the end marker, like [[[end]]] (sum: Rwh4n2CfQD).

This checksum allows Cog to detect if the output has been manually edited since it last processed the file – and if so, it will refuse to overwrite those changes.

You have to revert the manual edits or remove the checksum.You can also run Cog with a --check flag, which checks if a file is up-to-date.

I run this as a continuous integration task, to make sure I’ve updated my files properly.

What separates Cog from traditional templating engines like Jinja2 or Liquid is that it operates entirely in-place on the original file. Usually, you have a source template file and a build step which produce a separate output file, but with Cog, the source and the result are stored in the same document. Storing templates in separate files is useful for larger projects, but it’s overkill for something like my Caddyfiles.

Having everything in a single file makes it easy to resume working on a file managed with Cog. I don’t need to remember where I saved the build script or the template; I can operate directly on that single text file. If I come back to this project in six months, the instructions for how the file is generated are right in front of me.

The design also means that I’m not locked into using Cog. At any point, I could delete the Cog comments and still have a fully functional file.

Cog isn’t a replacement for a full-blown templating language, and it’s not the right tool for larger projects – but it’s indispensable for small amounts of automation. If you’ve never used it, I recommend giving it a look – it’s a handy tool to know.

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]

2026-01-31 15:43:53

On Sunday evening, I quietly swapped out a key tool that I use to write this site. It’s a big deal for me, but hopefully nobody else noticed.

The tool I changed was my static site generator. I write blog posts in text files using Markdown, and then my static site generator converts those text files into HTML pages. I upload those HTML pages to my web server, and they become available as my website.

I’ve been using a Ruby-based static site generator called Jekyll since late 2017, and I’ve replaced it with a Python-based static site generator called Mosaic. It’s a new tool I wrote specifically to build this website, so I know exactly how it works. I’m getting rid of a Ruby tool I only half-understand, in favour of a Python tool I understand well.

Nothing is changing for readers (yet). I tried hard to avoid breaking anything – URLs haven’t changed, pictures look identical, the RSS feed should be the same as before. Please let me know if you spot something broken!

You’ll see more changes soon, because I have lots of ideas to try this year. I want to make this website into more of a “digital garden”, getting even further away from a single list of chronologically ordered posts. I don’t want to build that with Jekyll – or to be precise, I don’t want to build it with Ruby.

I don’t want to sound dismissive of Jekyll. It’s an impressive project that powers thousands of sites, and I used it happily for over eight years. I pushed it to build a lot of custom and bespoke pages, and it handled it with ease.

Jekyll’s superpower is its theming and plugin system, which allow you to customise its behaviour. Want something that Jekyll can’t do out of the box? Create your own template or plugin. But those plugins have to be written in Ruby, the same language as Jekyll itself – and I only write Ruby to make blog plugins. I can do it, but I’m slow, I’m unsure, and writing Ruby has never felt familiar.

You can build a digital garden with Jekyll and Ruby – plenty of people already have – but I know I’d find it a difficult and frustrating experience. My lack of Ruby experience would slow me down.

While my Ruby knowledge has sat still, I’ve become a much better Python programmer. Since I set up Jekyll in 2017, I’ve worked on big Python projects with extensive tests, thorough data validation, and an explicit goal of longevity. I tried writing a Python static site generator in 2016 and I got stuck; a decade later and I’m ready for another attempt.

This isn’t just general Python expertise – I’ve written about how I’m using static websites for tiny archives, and all the surrounding tools are written in Python. Porting this website to Python means I can reuse a lot of that code.

I hacked together an experimental Python static site generator over Christmas, and I wrote it properly over the last few weeks. I named it “Mosaic” after the square-filled headers on every page, and I really like it. I already feel faster when I’m working on the site, writing a language I know properly.

Mosaic works like other static site generators: it reads a folder full of Markdown files, converts them to HTML, and writes the HTML into a new folder. And just like Jekyll and similar tools, I’m building on powerful open-source libraries.

Here’s a comparison of the key dependencies:

| Purpose | Jekyll | Mosaic |

|---|---|---|

| Templates | Liquid | Jinja |

| Markdown rendering | kramdown | Mistune |

| Image generation | ruby-vips | Pillow |

| Syntax highlighting | Rouge | Pygments |

| Data validation | json-schema | Pydantic |

| HTML linting | HTMLProofer | ??? |

Here are some thoughts on each.

Jinja is the templating engine used by Flask, a framework I’ve used to build dozens of small web apps, so I was very familiar with the basic syntax.

It’s similar to Liquid – both use {% … %} for operators and {{ … }} to insert values – so I could reuse my templates with only small changes.

The tricky part was replicating my custom tags, which I’d previously implemented using Jekyll plugins.

I had to write my own Jinja extensions, which are harder than writing Jekyll tags.

In Jinja, I have to interact directly with the lexer and parser, whereas a Jekyll plugin is a simple render function.

Mistune is a Markdown library I discovered while working on this project.

I used Python-Markdown previously, but Mistune is faster and easier to extend.

In particular, it provides a friendly way to customise the HTML output by overriding named methods.

For example, I can add an id attribute to my headings by overriding the header(text, level) method.

The tricky part about changing Markdown renderer is all the subtle differences in the places where Markdown isn’t defined clearly. Mistune and kramdown return the same output in 95% of cases, but there’s a lot of variation and broken HTML in the remaining 5%.

One particular difficulty was all my inline HTML.

This is one of my favourite Markdown features – you can include arbitrary HTML and it gets passed through as-is – and I make heavy use of it in this blog.

But kramdown and Mistune disagree about where inline HTML starts and ends, and Mistune was wrapping <p> tags around HTML that kramdown left unchanged.

I had to adjust my templates and whitespace to help Mistune distinguish Markdown and HTML.

I generate multiple sizes and formats for every image, so they get served in a fast and efficient way. I use Pillow to generate each of those derivatives.

Pillow is easier to install and supports a wider range of image formats than any of the Ruby gems I tried; it’s a highlight of the Python ecosystem.

The picture handling code has always been the thorniest bit of the website, and I hope that building it atop a nicer library will give me the space to simplify that code.

Rouge and Pygments are both capable libraries, and they return compatible HTML which made it easy to switch – I could reuse my CSS and my syntax highlighting tweaks.

I think Pygments theoretically supports highlighting a wider variety of languages, but I never found Rouge lacking so it’s not a meaningful improvement.

Every Markdown file in my site has YAML “front matter” for storing metadata, for example:

---

layout: post

title: Swapping gems for tiles

---Jekyll treats this as arbitrary data and doesn’t do any validation on it, which made it harder to change and keep consistent as the site evolved. I built a rudimentary validation layer using json-schema, but it was always an add-on.

In Mosaic, this front matter is parsed straight into a Pydantic model, so it’s type-checked throughout my code. This means I can write stricter validation checks, and catch more issues and inconsistencies before they break the website.

I’ve been using the HTMLProofer gem to check my HTML since 2019. It checks my HTML for errors like broken links or missing images, so I’m less likely to publish a broken page. It’s caught so many mistakes.

There’s no obvious Python equivalent, so for now I’m still running it as a separate step after I generate my HTML. It has a much lower overhead than running Jekyll so I’m not in a hurry to remove it – although eventually I’d like to reimplement the checks I care about with BeautifulSoup, so I can fully expunge Ruby.

I’m also considering using Playwright for some static site testing, but that’s a larger piece of work.

The name isn’t so important, because I’m the only person who will ever use this tool – but I discovered a fun nugget that’s too juicy not to share.

I named my tool “Mosaic” after the tiled headers that appear at the top of every page. Those headers are a design element I added in 2016, and I’m so fond of them now I can’t imagine getting rid of them. I later remembered that Mosaic is also the name of a discontinued web browser, and I like the “old web” vibes of that name. One of the best compliments I’ve ever received about this site was “it looks like something from the 1990s” – fast, clean, and not junked up with ads.

One of the bizarre things I discovered while writing this post is that it’s not the first time the names “Mosaic” and “Jekyll” have appeared alongside each other.

There’s a small historical island off the coast of Georgia (the USA one) called Jekyll Island. It includes bike trails, golf courses, a beach that’s been in several films… and a history museum called Mosaic. What are the chances?

I know nothing about Jekyll Island or the history of Georgia, but if I ever feel safe enough to return to the US, I’d love to visit.

I’ve been using Mosaic for several weeks and I’m really enjoying it. I wouldn’t recommend using it for anything else – it’s only designed to build this exact site – but all the source code is public, if you’d like to read it and understand how it works.

Switching to Mosaic has allowed me to start working on three improvements to the site:

Replace my “today I learned” (TIL) posts with “notes”. I really like how the TIL section has allowed me to write more frequent, smaller posts, but they’re still point-in-time snapshots. I want to replace them with notes that aren’t tied to a particular date, and instead can be living documents I update as I learn more.

Make the list of topics more useful. My current tags page is a wall of text, a list of 241 keywords with minimal context or explanation. Nobody is wading through that to find something interesting – I want to add some hierarchy to make it easier to read, and give a better overview of the site.

Fold my book reviews into my main site. My book reviews currently live on a separate site, which is only half-maintained. I’d like to merge them into the main site, let them benefit from the design improvements here, and start writing reviews of other entertainment.

I’ve had these ideas for months, and I’m excited to finally ship them, and bring this site closer to my idea of a “digital garden”

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]

2026-01-16 16:29:53

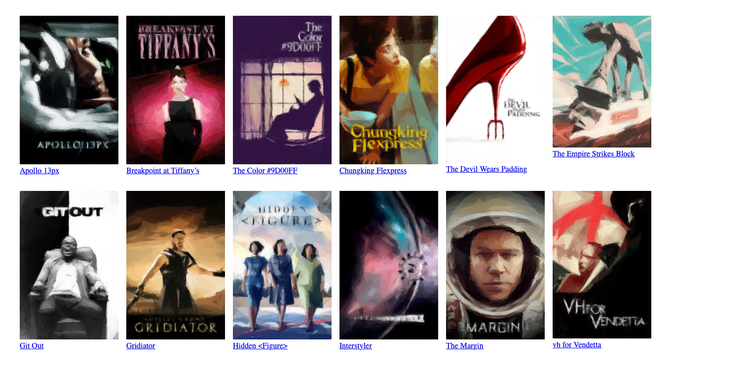

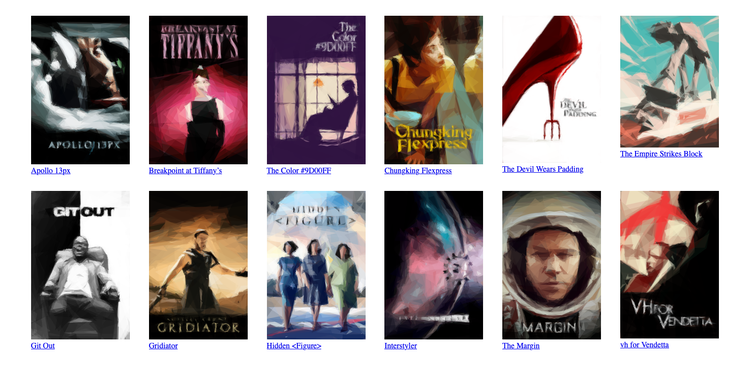

In my previous post, I needed a collection of movies to show off my CSS grid layout. The easy thing to do would be to use real movie posters, but I decided to have some fun and get a custom collection. I went to Blockbuster, HBO Max-Width, and Netflex, and this is what I got:

In this post, I’ll explain how I created this collection, and why I spent so much time on it.

Each title is a reference to a concept in CSS or web development:

- Apollo 13px

- Pixels (

px) are a unit of length in CSS. They’re a common way to define fixed sizes for text, borders, and spacing.- Breakpoint at Tiffany’s

- A breakpoint is the screen width at which a website’s layout changes – for example, when it switches from a single column on a phone to a multi-column grid on a desktop.

- The Color #9D00FF

- This is a hexadecimal colour code for a shade of purple. Hex codes are a common way to define colours in CSS.

- Chungking Flexpress

- Flexbox is a layout model that allows elements to “flex” – growing to fill extra space, or shrinking to fit into small spaces.

- The Devil Wears Padding

- The padding is the space inside an element, between its content and its border. In this list, the padding is the gap between the grey border and the text.

- The Empire Strikes Block

- A block-level element is one that starts on a new line and reserves the full width available, like a heading or a paragraph.

- Git Out

- Git is a version control tool used to track changes in source code. It’s the industry standard for managing web development projects.

- Gridiator

- CSS Grid is a layout system for arranging elements in rows and columns. Unlike Flexbox, which is one-dimensional, Grid is designed for two-dimensional layouts.

- Hidden <Figure>

- The

<figure>element is used to show an image with a caption, while thehiddenattribute tells browsers not to render a specific element on a page.- Interstyler

- The

<style>element is used to embed CSS rules directly in an HTML page. These rules are colloquially referred to as “styles”.- The Margin

- The margin is the space outside an element, the gap between it and its neighbours. In this list, the margin is the gap between the grey border and the text above it.

- vh for Vendetta

- The viewport is the visible area of a web page in your browser. The

vhunit stands for viewport height, where1vhis equal to 1% of the screen's height.

I’m pretty happy with this list, and with the amount of variety and wordplay I managed to fit into a dozen titles.

The trick to writing good puns is to write lots of puns, then throw away the bad ones. I only needed a dozen movies, but I had over thirty other titles that I didn’t use.

If the puns aren’t coming immediately, I write two lists: the phrases or words I want to parody, and the words I’m trying to shoehorn in. In this case, the first list had phrases like X-Men or Mission Impossible, and the second had words like pixel, margin, and flex.

This is where I reach for search engines – I won’t find anybody else making the exact puns I want, but I can find pre-existing lists of these building blocks. In this case, I looked at lists of famous and iconic films, and I read web development tutorials and glossaries. I leant toward popular films so more people would get the reference; a pun on an obscure film would likely be missed.

As I build the two lists, I start to spot connections, like the fact that X-Men could become Flex-Men. I write down all my ideas, even the bad ones – often a bad idea is the jumping off point for a good one. For example, an early idea was Block to the Future, which isn’t very good, but later I realised I could use Back/Block for The Empire Strikes Block instead, which is much better.

If this was a purely text-based exercise, the titles would be enough – but I also needed posters.

I needed some posters to go with the titles, but what to use?

I wanted to use the movie posters because many films have iconic posters, and that would help people recognise the pun – but I didn’t want to use the real movie posters, because they often show the title. That would contradict my text, not help it.

But I do have an image editor, and while I lack the Photoshop skills to replace the title in a convincing way, I can make text that looks okay if you squint – and that gave me an idea.

Several years ago, I used Michael Fogleman’s Primitive tool to create some wallpapers. Primitive redraws images with a simple geometric shapes, adding one shape at a time, trying to get closer and closer to the original image.

Here’s an example, in which my face has been redrawn as several hundred triangles:

This gives a recognisable version of the image, but it’s a distinct style and you won’t mistake it for the real thing.

For each movie I was considering, I downloaded a poster from The Movie Databaase, and I used Primitive to blur it. Sometimes the original title would appear through the blur, in which case I used an image editor to replace the title and re-blurred it. The blurring meant I could get away with a rough edit – for example, I didn’t need the exact font – because any imperfections would be blurred away by Primitive.

This added a new dimension to my search for puns – I wanted movie posters that would still be recognisable after this blurring. This ruled out posters that are very busy, because it’s difficult to distinguish individual elements after the blurring. I looked at lists of iconic movie posters, which often have clear, distinct shapes that hold up well when converted into triangles.

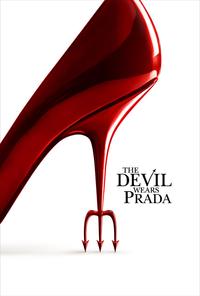

One of the best examples of an iconic poster is The Devil Wears Prada. I know nothing about the film, but I remember the poster with the big red heel. When you blur the poster with Primitive, it becomes recognisable almost immediately. This is what it looks like with 5, 25, and 50 triangles:

I had a year where all my desktop wallpapers were photos that I’d blurred using Primitive, and I’ve been waiting for a chance to use it in a bigger project. I’m really pleased with the result – it lets me lean into the titles I’ve created, and it gives the whole collection a coherent appearance.

I picked a dozen movies and started writing the article. But as I was taking screenshots of the movie grid, I noticed that my initial selection wasn’t very representative. Ten of the twelve films had all-or-mostly men in the main roles, and all of the lead characters were white.

I was tempted to ignore this problem, because this is just a fake collection for a blog post and does it really matter? But that was disingenuous – I cared enough to put in all this effort, so it must be a meaningful selection to me. I wanted a more diverse and interesting selection.

I looked for lists of famous movies which centre women and non-white characters, and added several to my made-up collection. Ideally I’d also have some movies that centre queer or disabled characters, but I couldn’t find any with an iconic poster or a pun-worthy title.

I made a lot of puns and posters, including a couple of personal favourites that I cut from the post:

Fifty Shades of Grey became Fifty Shades of #999 and was the first movie where I considered replacing a colour with a hex code. I swapped this out for The Colour Purple when I was trying to create a more diverse list, and replacing a mostly-grey poster with a pop of colour helped too.

X-Men became Flex-men, and I’m really sad I couldn’t use that pun. This was let down by the poster – the original X-Men branding is very prominent and would be hard to change, and all of the colourful X-Men posters are very busy with lots of characters.

Home Alone became Home Align, which is a weaker pun but another easily-recognisable poster.

I had good reasons to cut all of them, and the selection is better off without them – but maybe they’ll reappear in a future post.

This is a lot of effort for placeholder data in a single blog post. I did it because it was fun, and it helped me enjoy writing the rest of the post. Every time I thought of another title or saw a poster in a screenshot, it made me smile. That’s enough of a reason.

This sort of fun detail is why I like having a personal blog which isn’t a business or an income stream. I write because I enjoy it, and I can make decisions that don’t make commercial sense because it’s not a commercial website. This side quest had terrible return on investment if you only care about time and money – but it was fantastic for joy.

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]

2026-01-14 16:38:52

I’ve been organising my local movie collection recently, and converting it into a static site. I want the homepage to be a scrolling grid of movie posters, where I can click on any poster and start watching the movie. Here’s a screenshot of the design:

This scrolling grid of posters is something I’d like to reuse for other media collections – books, comics, and TV shows.

I wrote an initial implementation with CSS grid layout, but over time I found rough edges and bugs. I kept adding rules and properties to “fix” the layout, but these piecemeal changes introduced new bugs and conflicts, and eventually I no longer understood the page as a whole. This gradual degradation often happens when I write CSS, and when I no longer understand how the page works, it’s time to reset and start again.

To help me understand how this layout works, I’m going to step through it and explain how I built the new version of the page.

This is a list of movies, so I use an unordered list <ul>.

Each list item is pretty basic, with just an image and a title.

I wrap them both in a <figure> element – I don’t think that’s strictly necessary, but it feels semantically correct to group the image and title together.

<ul id="movies">

<li>

<a href="#">

<figure>

<img src="apollo-13px.png">

<figcaption>Apollo 13px</figcaption>

</figure>

</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#">

<figure>

<img src="breakpoint-at-tiffanys.png">

<figcaption>Breakpoint at Tiffany’s</figcaption>

</figure>

</a>

</li>

...

</ul>I did wonder if this should be an ordered list, because the list is ordered alphabetically, but I decided against it because the numbering isn’t important.

Having a particular item be #1 is meaningful in a ranked list (the 100 best movies) or a sequence of steps (a cooking recipe), but there’s less significance to #1 in an alphabetical list. If I get a new movie that goes at the top of the list, it doesn’t matter that the previous #1 has moved to #2.

This is an unstyled HTML page, so it looks pretty rough:

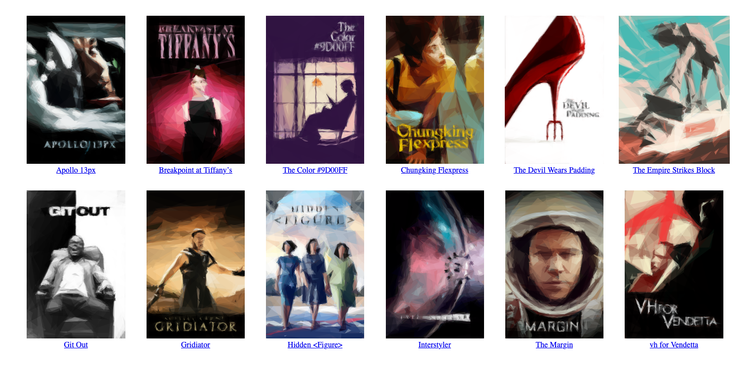

Next, let’s get the items arranged in a grid. This is a textbook use case for CSS grid layout.

I start by resetting some default styles: removing the bullet point and whitespace from the list, and the whitespace around the figure.

#movies {

list-style-type: none;

padding: 0;

margin: 0;

figure {

margin: 0;

}

}Then I create a grid that creates columns which are 200px wide, as many columns as will fit on the screen. The column width was an arbitrary choice and caused some layout issues – I’ll explain how to choose this properly in the next step.

#movies {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, 200px);

column-gap: 1em;

row-gap: 2em;

}By default, browsers show images at their original size, which means they overlap each other. For now, clamp the width of the images to the columns, so they don’t overlap:

#movies {

img {

width: 100%;

}

}With these styles, the grid fills up from the left and stops as soon as it runs out of room for a full 200px column. It looks a bit like an unfinished game of Tetris – there’s an awkward gap on the right-hand side of the window that makes the page feel off-balance.

We can space the columns more evenly by adding a justify-content property which tells the browser to create equal spacing between each of them, including on the left and right-hand side:

#movies {

justify-content: space-evenly;

}With just ten CSS properties, the page looks a lot closer to the desired result:

After this step, what stands out here is the inconsistent heights, especially the text beneath the posters. The mismatched height of The Empire Strikes Block is obvious, but the posters for The Devil Wears Padding and vh for Vendetta are also slightly shorter than their neighbours. Let’s fix that next.

Although movie posters are always portrait orientation, the aspect ratio can vary. Because my first grid fixes the width, some posters will be a different height to others.

I prefer to have the posters be fixed height and allow varied widths, so all the text is on the same level. Let’s replace the width rule on images:

#movies {

img {

height: 300px;

}

}This causes an issue with my columns, because now some of the posters are wider than 200px, and overflow into their neighbour. I need to pick a column size which is wide enough to allow all of my posters at this fixed height. I can calculate the displayed width of a single poster:

Then I pick the largest display width in my collection, so even the widest poster has enough room to breathe without overlapping its neighbour.

In my case, the largest poster is 225px wide when it’s shown at 300px tall, so I change my column rule to match:

#movies {

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, 225px);

}If I ever change the height of the posters or get a wider poster, I’ll need to adjust this widths.

If I was adding movies too fast for that to be sustainable, I’d look at using something like object-fit: cover to clip anything that was extra wide.

I’ve skipped that here because I don’t need it, and I like seeing the whole poster.

If you have big columns or small devices, you need some extra CSS to make columns and images shrink when they’re wider than the device, but I can ignore that here. A 225px column is narrower than my iPhone, which is the smallest device I’ll use this for. (I did try writing that CSS, and I quickly got stuck. I’ll come back to it if it’s ever an issue, but I don’t need it today.)

Now the posters which are narrower than the column are flush left with the edge of the column, whereas I’d really like them to be centred inside the column. I cam fix this with one more rule:

#movies {

li {

text-align: center;

}

}This is a more subtle transformation from the previous step – nothing’s radically different, but all the posters line up neatly in a way they didn’t before.

Swapping fixed width for fixed height means there’s now an inconsistent amount of horizontal space between posters – but I find that less noticeable. You can’t get a fixed space in both directions unless all your posters have the same aspect ratio, which would mean clipping or stretching. I’d rather have the slightly inconsistent gaps.

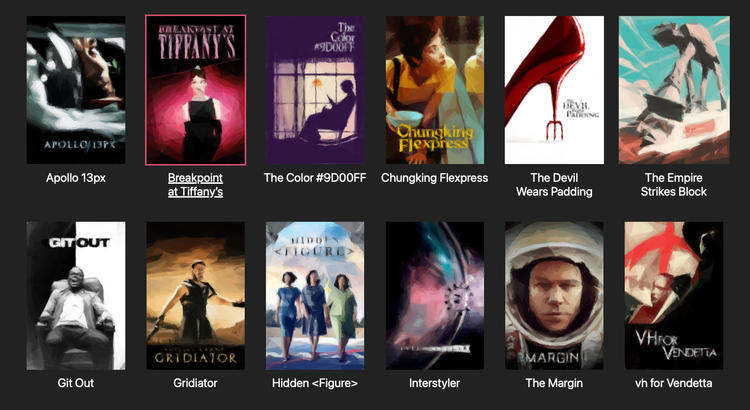

The white background and blue underlined text are still giving “unstyled HTML page” vibes, so let’s tidy up the colours.

The next set of rules change the page to white text on a dark background. I use a dark grey, so I can distinguish the posters which often use black:

body {

background: #222;

font-family: -apple-system, sans-serif;

}

#movies {

a {

color: white;

text-decoration: none;

}

}Let’s also make the text bigger, and add a bit of spacing between it and the image. And when the title and image are more spaced apart, let’s increase the row spacing even more, so it’s always clear which title goes with which poster:

#movies {

grid-row-gap: 3em;

figcaption {

font-size: 1.5em;

margin-top: 0.4em;

}

}The movie title is a good opportunity to use text-wrap: balance.

This tells the browser to balance the length of each line, which can make the text look a bit nicer.

You’ll get several lines of roughly the same length, rather than one or more long lines and a short line.

For example, it changes “The Empire Strikes // Block” to the more balanced “The Empire // Strikes Block”.

#movies {

figcaption {

text-wrap: balance;

}

}Here’s what the page looks like now, which is pretty close to the final result:

What’s left is a couple of dynamic elements – hover states for individual posters, and placeholders while images are loading.

As I’m mousing around the grid, I like to add a hover style that shows me which movie is currently selected – a coloured border around the poster, and a text underline on the title.

First, I use my dominant_colours tool to get a suitable tint colour for use with this background:

$ dominant_colours gridiator.png --best-against-bg '#222'

▇ #ecd3abThen I add this to my markup as a CSS variable:

<ul id="movies">

...

<li style="--tint-colour: #ecd3ab">

<a href="#">

<figure>

<img src="gridiator.png">

<figcaption>Gridiator</figcaption>

</figure>

</a>

</li>

...

</ul>Finally, I can add some hover styles that use this new variable:

#movies {

a:hover {

figcaption {

text-decoration-line: underline;

text-decoration-thickness: 3px;

}

img {

outline: 3px solid var(--tint-colour);

}

}

}I’ve added the text-decoration styles directly on the figcaption rather than the a, because browsers are inconsistent about whether those properties are inherited from parent elements.

I used outline instead of border so the 3px width doesn’t move the image when the style is applied.

Here’s what the page looks like when I hover over Breakpoint at Tiffany’s:

We’re almost there!

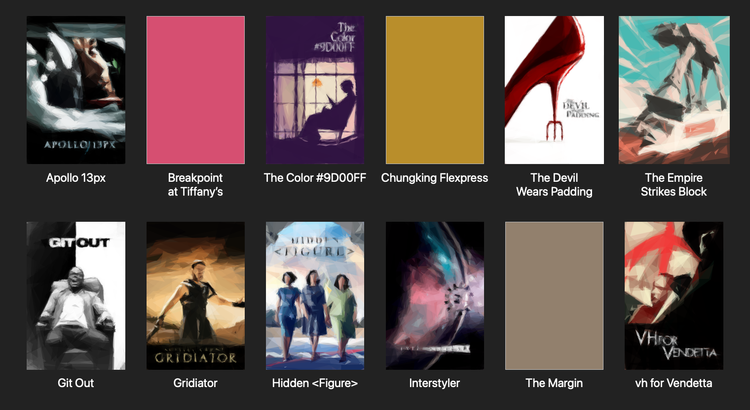

As my movie collection grows, I want to lazy load my images so I don’t try to load them all immediately, especially posters that aren’t scrolled into view. But then if I scroll and I’m on a slow connection, it can take a few seconds for the image to load, and until then the page has a hole. I like having solid colour placeholders which get replaced by the image when it loads.

First I have to insert a wrapper <div> which I’m going to colour, and a CSS variable with the aspect ratio of the poster so I can size it correctly:

<ul id="movies">

...

<li style="--tint-colour: #ecd3ab; --aspect-ratio: 510 / 768">

<a href="#">

<figure>

<div class="wrapper">

<img src="gridiator.png" loading="lazy">

</div>

<figcaption>Gridiator</figcaption>

</figure>

</a>

</li>

...

</ul>We can add a coloured background to this wrapper and make it the right size:

#movies {

img, .wrapper {

height: 300px;

aspect-ratio: var(--aspect-ratio);

}

.wrapper {

background: var(--tint-colour);

}

}But a <div> is a block element by default, so it isn’t centred properly – it sticks to the left-hand side of the column, and doesn’t line up with the text.

We could add margin: 0 auto; to move it to the middle, but that duplicates the text-align: center; property we wrote earlier.

Instead, I prefer to make the wrapper an inline-block, so it follows the existing text alignment rule:

#movies {

.wrapper {

display: inline-block;

}

}Here’s what the page looks like when some of the images have yet to load:

And we’re done!

There’s a demo page where you can try this design and see how it works in practice.

Here’s what the HTML markup looks like:

<ul id="movies">

<li style="--tint-colour: #dbdfde; --aspect-ratio: 510 / 768">

<a href="#">

<figure>

<div class="wrapper">

<img src="apollo-13px.png" loading="lazy">

</div>

<figcaption>Apollo 13px</figcaption>

</figure>

</a>

</li>

...

</ul>and here’s the complete CSS:

body {

background: #222;

font-family: -apple-system, sans-serif;

}

#movies {

list-style-type: none;

padding: 0;

margin: 0;

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, 225px);

column-gap: 1em;

row-gap: 3em;

justify-content: space-evenly;

figure {

margin: 0;

}

li {

text-align: center;

}

a {

color: white;

text-decoration: none;

}

figcaption {

font-size: 1.5em;

margin-top: 0.4em;

text-wrap: balance;

}

a:hover, a#tiffanys {

figcaption {

text-decoration-line: underline;

text-decoration-thickness: 3px;

}

img {

outline: 3px solid var(--tint-colour);

}

}

img, .wrapper {

height: 300px;

aspect-ratio: var(--aspect-ratio);

}

.wrapper {

background: var(--tint-colour);

display: inline-block;

}

}I’m really happy with the result – not just the final page, but how well I understand it. CSS can be tricky to reason about, and writing this step-by-step guide has solidified my mental model.

I learnt a few new details while checking references, like the outline property for hover states, the way text-decoration isn’t meant to inherit, and the fact that column-gap and row-gap have replaced the older grid- prefixed versions.

This layout is working well enough for now, but more importantly, I’m confident I could tweak it if I want to make changes later.

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]

2026-01-13 02:01:38

For nearly a decade, the header of this website has been decorated with a mosaic-like pattern of coloured squares. I can choose a colour for individual posts or pages, and that tints the title, the links, and the header. It adds some texture and visual interest, without being too distracting.

The implementation is pretty straightforward: I have one function that generates the coordinates of each square, and another that generates varying shades of the tint colour. Put those together, and it draws the header image.

I recently improved the way I choose the shades of the tint colour, which makes the headers look more coherent, especially in dark mode. The change is subtle, but a definite improvement.

Before, this is how I generated the shades:

I was trying to create colours which looked similar and varied only in lightness, so you’d see lighter or darker shades of the tint colour. My headers are PNG images, which are usually saved as sRGB, which is I why I convert back in the final step.

Here’s what the old code looked like:

require 'color'

# Given a hex colour as a string (e.g. '#123456') generate

# an infinite sequence of colours which vary only in brightness.

def get_colours_like(hex)

seeded_random = Random.new(hex[1..].to_i(16))

hsl = Color::RGB.by_hex(hex).to_hsl

min_luminosity = hsl.luminosity * 7 / 8

max_luminosity = hsl.luminosity * 8 / 7

luminosity_diff = max_luminosity - min_luminosity

Enumerator.new do |enum|

loop do

new_hsl = Color::HSL.from_values(

hsl.hue,

hsl.saturation,

min_luminosity + (seeded_random.rand * luminosity_diff)

)

enum.yield new_hsl.to_rgb

end

end

endI seeded the random generator so it always returned the same colours – this meant my local dev environment and web server would always generate identical header images. Note that it’s seeded based on the colour, so different tint colours will have light/dark squares in different places.

All the colour calculations are done by Austin Ziegler’s excellent color gem, which saved me from implementing colour conversions myself.

This approach is simple, but it has problems. Varying the lightness by proportion means the range varied from colour to colour – headers for dark colours didn’t have enough contrast, while light colours had too much contrast.

Here are three examples – notice how the dark header is almost solid colour, while the light header has enough contrast to become distracting:

This heuristic worked for the first colour I tried (#d01c11, the site’s original tint colour) but it breaks down as I’ve added more colours, especially in dark mode.

I could replace the percentages with fixed offsets – for example, plus or minus 25% lightness – but this wouldn’t fix the problem. Humans aren’t machines; we don’t perceive colours as linear numerical values. The human eye is more sensitive to some colours than others, so the same numerical jump in HSL doesn’t feel like the same visual difference.

Let’s look at another example, where I’ll fix the hue and saturation, and step the lightness by 25%. These differences don’t feel the same:

There are alternative colour spaces like OKLCH and CIELAB which try to capture the nuances of human biology and how we interpret colours, and that’s where I looked at for a replacement.

The CIELAB colour space is based on opponent process theory, which suggests that we perceive colour as a battle of three opposing pairs: black vs. white, red vs. green, and blue vs. yellow. Think about how you never see a reddish-green or a blueish-yellow – these colours are opposites.

These three pairs give us the three coordinates in CIELAB space:

(The other three letters stand for Commission internationale de l’éclairage, the standards body who developed CIELAB in 1976.)

Within this colour space, we can calculate the perceptual difference between two colours. Ideally, that numerical distance should match our human perception of the change. The goal is perceptually uniformity: if you move a fixed numerical distance anywhere in the space, the “amount” of change should feel the same to a human observer.

That’s much easier said than done: the measurement formulas (like Delta E) have been refined over decades, and deficiences have been found in CIELAB, especially for shades of blue. Newer spaces like OKLAB try to capture the nuances of human biology even more accurately. But for the purpose of my header images, CIELAB is good enough, and a big improvement over HSL.

One place I already use CIELAB is in my tool for extracting dominant colours. I’m using k‑means clustering to group colours that are “close” together, and it makes sense to measure closeness using perceptual distance.

The Ruby gem I’m using supports CIELAB but not OKLAB, which also informed my decision. Colour maths is complicated, and I’d rather use an existing implementation than write it all myself.

Here’s my new heuristic:

To find the bounds, I do a binary search on the possible lightness values to find the perceptual lightness which gets me closest to the target distance.

If I’m looking for the lighter shade, I search the range .

If I’m looking for the darker shade, I search the range .

Here’s the code:

require 'color'

# Find the perceptual lightness of a CIELAB colour that's a specific

# perceptual difference (target_distance) from the original colour, while

# maintaining the original hue and colourfulness.

def lightness_at_distance(original_lab, direction, target_distance)

# 1. Define the search range for L*

if direction == 'lighter'

low_l = original_lab.l

high_l = 100

else

low_l = 0

high_l = original_lab.l

end

# 2. Run a binary search on L*

best_lab = original_lab

best_delta = 0

15.times do

mid_l = (low_l + high_l) / 2.0

candidate_lab = Color::CIELAB.from_values(mid_l, original_lab.a, original_lab.b)

candidate_delta = original_lab.delta_e2000(candidate_lab)

# Are we closer than the current best colour? If so, replace it.

if (candidate_delta - target_distance).abs < (best_delta - target_distance).abs

best_lab = candidate_lab

best_delta = candidate_delta

end

if candidate_delta < target_distance

# We need more distance, move away from the original L*

direction == 'lighter' ? (low_l = mid_l) : (high_l = mid_l)

else

# We've gone too far, move back toward the original L*

direction == 'lighter' ? (high_l = mid_l) : (low_l = mid_l)

end

end

best_lab.l

endThen I can write a very similar function to what I wrote for HSL:

# Given a hex colour as a string (e.g. '#123456') generate

# an infinite sequence of colours which vary only in lightness.

def get_colours_like(hex)

seeded_random = Random.new(hex[1..].to_i(16))

lab = Color::RGB.by_hex(hex).to_lab

min_lightness = lightness_at_distance(lab, 'darker', 6)

max_lightness = lightness_at_distance(lab, 'lighter', 6)

lightness_diff = max_lightness - min_lightness

Enumerator.new do |enum|

loop do

new_lab = Color::CIELAB.from_values(

min_lightness + (seeded_random.rand * lightness_diff),

lab.a,

lab.b

)

# Discard colours which don't map cleanly from CIELAB to sRGB

if new_lab.delta_e2000(new_lab.to_rgb.to_lab) > 1

next

end

enum.yield new_lab.to_rgb

end

end

endOne gotcha is that CIELAB is a wider range than sRGB, so CIELAB colours don’t always map cleanly into sRGB. For example, certain bright colours like neon green may lose their vibrancy when converted from CIELAB to sRGB.

When it does the conversion, the color gem automatically clamps colours to fit into the sRGB space, but this creates some unusually dark or bright squares. I check if this clipping has occurred by converting back to CIELAB and looking at the distance – if there’s too much drift, I discard the colour and pick another. This is another subtle difference, but I think it improves the overall vibe.

Let’s look at the results, which compare the HSL heuristic (top), the original tint colour (middle), and the CIELAB heuristic (bottom):

The dark squares have a bit more variety, while the light squares have much less and avoid the bright and noticeable shades. It’s a particular improvement in dark mode, where I always use light tint colours. There’s almost no difference for the middle colour, which makes sense because it was how I designed the original heuristic. It already looked pretty good.

The new colours are closer to what I want: a bit of subtle texture, not loud enough to draw attention. I switched to them a fortnight ago, and nobody noticed. It’s small refinement, not a radical change.

[If the formatting of this post looks odd in your feed reader, visit the original article]