2026-02-13 19:46:10

First, a caveat: if you think you've spotted a noble lie that seems to work for people, such that possibly if everyone knew the truth we'd all be worse off, should you write a blogpost about it?

I don't fully know if you should, but I am fundamentally a thought-gossip and if I think of an idea I just want to tell everyone, ruat cælum. So here you go.

I think a lot of typologies and systems (such as attachment theory, enneagram, astrology and so on) basically function to allow people whose relationship has soured to attempt a "reset" while blaming neither party.

If Alice and Bob have been fighting, and they've both dug their heels in, and they want to un-dig themselves, but that would mean admitting one (or more) of them is wrong.... it's so much easier to not to.

But then suppose Alice reads a book about how everyone (conversationally) is either a tardigrade or a barnacle, and tardigrades and barnacles often misunderstand each other because of their different world-models, but neither is fundamentally wrong, and Alice is a tardigrade and Bob is a barnacle.... well, suddenly we have a way to reset the conflict without either party admitting error.

This doesn't even mean that the system or typology is entirely pointless or arbitrary: in theory, it could also be pointing at a real difference in people's models of the world, of which there are many. But that isn't strictly necessary, the typology can be trivial or even false, so long as it gives everyone an excuse to forgive and forget, and try once more to make the perilous journey across the seas to another soul.

(Happy Valentines day everyone!)

2026-02-11 19:34:27

25yo straight man seeking love, in or around Lausanne. Word nerd who loves etymology, typography, translation, etc. Sings in an anarchist choir and plays the sitar. I’ll fix your bike and make you coffee—will you fill in the last clues of my crossword? 👀👉👈

If this might be you or someone you know, reply to this email to be connected with the sender. Or submit your own ATVBT Personal here to find love, jobs, friends, or more.

One thing I think is weird about modernity is that we each live in our own algorithmic bubbles and I have no idea what anyone else is watching. So I thought it would be fun to just... share the shortform video channels that get fed me the most.

I can only describe this as borscht belt humour, but in Irish: a young guy does a series of comedy skits with his parents, with the sequence usually being 1) son asks a question, 2) dad gives a stupid answer, 3) son makes a stupid pun, 4) dad's response insults mum, 5) mum exasperatedly shouts the dad's name (CATHAL KELLY!!) from offscreen. I don't know what to tell you, there's a system and it works.

In the early videos the mum never appeared on camera, but recently she's relented to being onscreen, and I find that oddly sweet and touching.

A young Japanese guy sings and dances to his anthem about The Pain Of Discipline Or The Pain Of Regret, encouraging you to choose the former.

He's not technically "good" at any of one of the sing/dance/write components, but somehow the package is extremely charming.

The algorithm feeds me ~infinite variations of the above, just him singing and dancing to these little motivational snippets against different backgrounds. Why? Who knows, I'll still watch it.

A bunch of landscapers doing various cute / kind / stupid video-jokes about 1) life on the worksite and/or 2) how much they love each other.

I'm a little sad to realise now that the channel is owned by their boss and they might be doing it under duress, which makes it much less cute.

This channel is pretty successful now, and they're definitely investing a ton of time and effort to develop short clips and get chosen by the algorithm, so there's a weird three-way relationship now between the algorithm and the algorithm-gamers and me. But hey, they're good at what they do.

I think the trick to this show is that the guys genuinely seem to like each other, and are comfortable making fun of each other & being made fun of – actual chemistry is so hard to fake, and so most corporate-run shows where the hosts didn't choose each other don't work. Of all the shortform clips I've been fed, this is the only one that has led me to wasting hours of this brief and precious life watching longform videos, so... well done Kevin & co I suppose?

Looking at this list, what strikes me is how inexplicable the algorithm still feels to me, and how hard it is for me to believe that THIS is the material that is truly optimized to keep me watching.

If you ask my conscious brain (non-subconscious brain? Base-conscious brain?) I would say I like each of these channels but don't love them. I also would have thought that more variety would be more interesting, and yet The Algorithm seems convinced that most of the time the next thing to feed me is one of a small handful of repetitive channels. And incredibly well-paid people are spending their lives building addictive algorithms, and presumably they (the algorithms, if not the people) know me better than I know myself?

That said, one of the weird parts of algoland is that they're not trying to make you happy, exactly, they're just trying to keep you watching. Maybe the things that keep me watching are more mediocre than the things I'd be excited about? Who knows, who knows.

2026-02-11 00:50:10

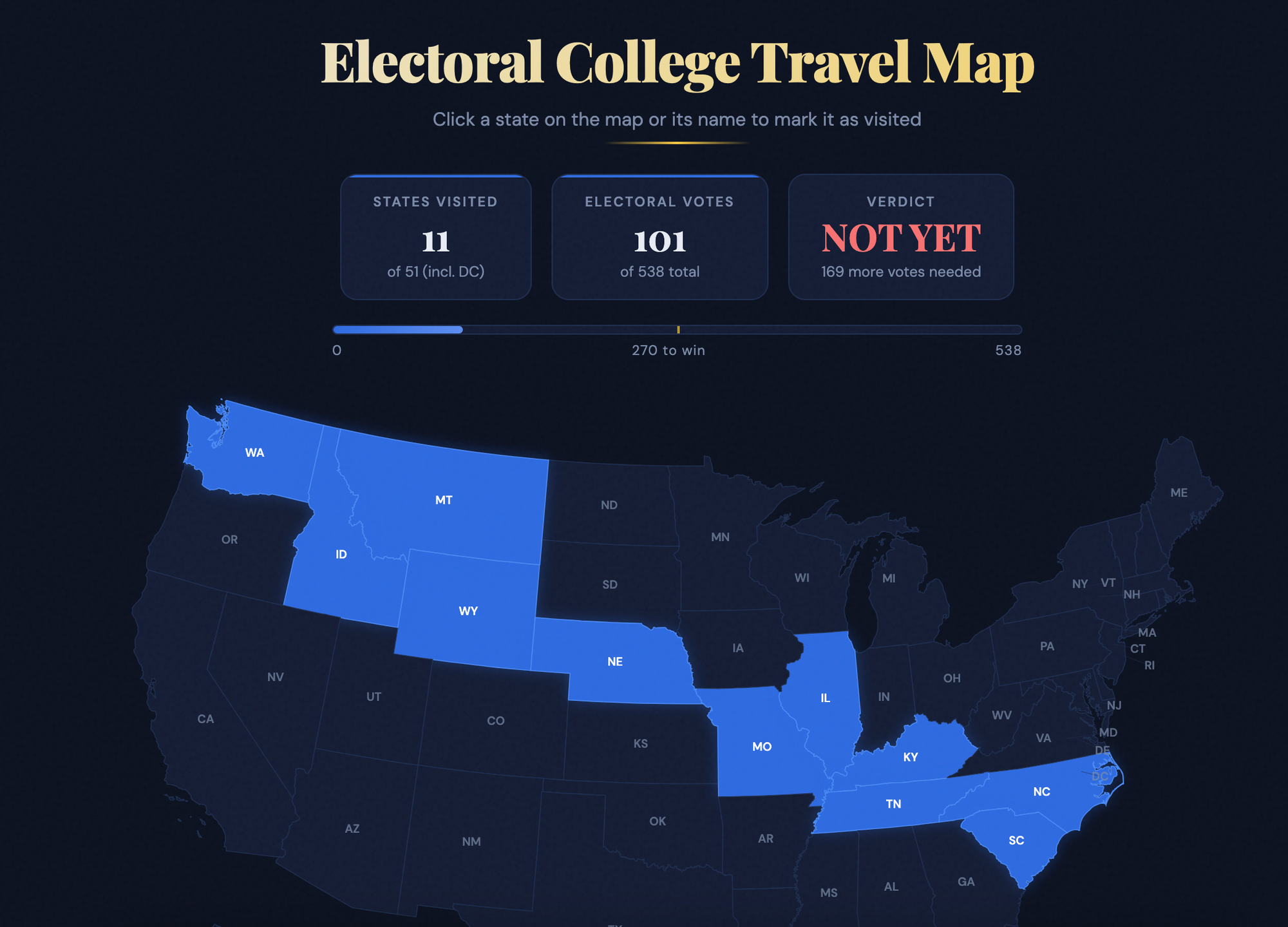

Did you ever ask yourself: hey, if I added up the electoral college votes of all the US states I've visited, would it be enough to win the presidency? Ask no more: use my Electoral College Travel Map to find out for sure, and/or plan future travels to get over the line.

2026-02-09 19:20:27

I try not to Advocate Stuff too much, but here's a thing I do that I think you should too: when you have a good experience with a big company:

1) search for the primary customer service contact on https://www.elliott.org/company-contacts/

2) send that person an email appreciating the thing

Personally this mostly happens to me with good call center support, but you could really do it with anything.

I think this is valuable because:

a) customer service people get tons of complaints, it's probably genuinely meaningful for them to occasionally have someone email their manager to compliment them instead of complain about them

b) it just feels like cosmically the right thing to do, in a world where (mostly) people only email to complain and never to compliment

c) in some small way, I truly believe that this kind of thing can shape company incentives. I really want companies to invest in e.g. high quality phone-based human-operated customer service, and that's not cheap, and there will inevitably be factions within the company arguing for choosing a cheaper and worse option instead.

In at least some cases, I believe you can meaningfully strengthen the hand of the internal factions who advocate for spending money on better service if you can help them show up to meetings with a slide saying HERE IS AN EMAIL FROM A LITERAL HAPPY CUSTOMER SAYING HOW MUCH THEY APPRECIATE THE EXACT THING I HAVE ADVOCATED SPENDING MONEY ON.

I cannot prove this is true but I think it's how stuff works in the world, and if you want to see more of something you should enable the people who are trying to make it happen. And hey, if it's not-true, the first points still hold anyway.

2026-02-07 00:11:20

When I got a new job via a friend's tweet, I originally thought the org was going to give her a referral bonus (equal to about a week's salary). It turned out they wouldn't, so I sent her that money instead.

(Confession: I was dumb about this and didn't think about the pre-tax/post-tax issue, so effectively ended up sending her twice as much money as I should have – remember your taxes!).

This was a lot of money to me, and I hadn't yet earned the higher salary, so the decision was expensive, but it felt morally right. I want to reward people for sending me good things, and in the long run the job should have been worth a lot more to me than the referral cost.

I want there to be more of a norm of social acceptability for paying post-hoc bounties for good things people send your way: new jobs, lovers, places to live. I'm not sure how to make that norm happen.

I think in most situations it wouldn't make sense to have a formal contract around this, or to declare a fixed amount in advance: we probably need the flexibility to differentiate the bounty value of an offhand reference that leads accidentally to a job, from a warm introduction but no followup, from someone who holds your hand through the whole application process.

I think a lot of damage has been done by rules of thumb like "when you go to a wedding, give a gift that equals the cost of your plate," rather than some complicated formula of your income and their incomes and how close you are and how unnecessarily expensive the weddings was. Similarly, I think a fixed % bounty for introductions would be bad.

But I don't think it would be crazy to have a norm that if someone sets you up with a great job/partner/home, you're expected to send them something substantial at some point in the future as a thank you.

I do think there's something complicated here where under-compensating someone can feel much worse than not-compensating them at all. I have twice now been in situations where I set people up with career opportunities that have netted them millions of dollars in expectation, and where their response was "cool, I owe you dinner!" And, you know, I don't object to the dinner in theory but in both cases the way they said it made it clear to me they thought the dinner was fair recompense for the connection, and I was like.... no?, I'd rather get nothing, because previously I was a generous guy who did someone a nice favour, and now I'm just a chump who makes hilariously bad trades. (Similarly, I'm happy to do things and receive nothing but gratitude from people who are actually nice and actually share gratitude).

I also wonder if there's some way to signal to strangers that you're an adherent of the Bounty Community. For example, many of us get emails from near strangers asking to Pick Our Brains for job opportunities. I would feel more positively about these emails if the person had a line in their email signature affirming that they were a Bounty Keeper, who would actually give me something if my help was helpful to them, rather than (say) wasting my time with questions they could have answered online, inartfully transitioning to asking me for job leads, and then ghosting me after that.

2026-02-04 19:28:50

I just love coming up with dating app ideas; my previous batch here.

Classic swipe-based dating app, BUT you pay per swipe and the cost goes up by the number of un-responded messages the person already has in their inbox. So you're incentivized to swipe and message people who AREN'T already sitting on 1000 unread matches.

(This could be a literal pay-per-swipe, i.e. each swipe has a cost and when you see someone's profile you also see "$2.31 to swipe right on this person". But I think non-economists would find this offputting, so it wouldn't fly; you can achieve the same by making people pay $30 per month to get a certain number of Points, and then matching costs 1/2/3 points per match depending on how full their inbox is).

Ok, here's how it goes: suppose you're secretly into something mildly embarrassing, like reading ATVBT. Maybe you're not even embarrassed about it!, but still you don't need every stranger on a dating app knowing about your, ahem, predilection. You want to meet other people who share this niche interest, but currently the only way to do that is to have it loud and proud on your profile, and/or date a bunch of random people and wait to see if any of them are into this thing. Inefficient!

What would be great is if dating apps let you set a secret "flag" with the niche thing you're into, and then preferentially match you with other people who have the same flag. It wouldn't be deterministic, so you always have plausible deniability, it's just that you know that when the app tells you "we think you'll like THIS person", there's a reasonable chance that this is a secret signal: here is one of the few other sickos who read this stupid newsletter.

You can then do an exciting flirtatious dance around each other as you slowly figure out whether this is the case: it's funny we're meeting on a dating app, you say; I was just reading a blogpost with weird ideas for dating apps, as you scan their face for that sweet, guilty look of recognition.

If it turns out the person sucks in other ways, you can always feign innocence. "A blogpost? Nobody reads those any more." And then just swipe to the next.

If you run a dating app and would like to pay me to work on it, please email me at [email protected]. I am extremely serious, I missed a fork in the road ten years back to work on dating apps and have regretted it ever since.