2026-03-12 23:31:11

When we hear “stateless architecture”, we often think it means building applications that have no state. That’s the wrong picture, and it can lead to confusion about everything that follows.

Every application has a state, such as user sessions, shopping carts, authentication tokens, and preferences. All of that is state. It’s the application’s memory and the very thing that makes personalized digital experiences possible. Without it, every visit to a website would feel like the first time.

In other words, stateless architecture doesn’t eliminate state but relocates it. Understanding where the state moves, why we move it, and what that move costs us is essential for developers.

In this article, we will understand the nuances of stateless architecture in more detail.

2026-03-11 23:31:15

Join Alex Casalboni (Developer Advocate @ Unleash) for a deep dive on how to design resilient AI workflows to make reversibility a foundational mechanism and release AI-generated code with confidence.

AI writes code in seconds, but reviews take hours. Don’t let this gap slow you down.

Watch our recent webinar to learn how FeatureOps helps you manage risk, contain blast radius, and maintain control over fast-moving agentic workflows.

In this webinar, you’ll learn how to:

Reduce blast radius for AI-generated changes

Separate deployment from exposure at runtime

Build reversibility into agent planning and shipping

Imagine you’re watching a video with AI-generated subtitles. The speaker is mid-sentence, clearly still talking, gesturing, making a point. But the subtitles just vanish, and there are a few seconds of blank screen. Then they reappear as if nothing happened.

This looks like a bug. But it’s a side effect of the AI being too good at translation.

Vimeo’s engineering team ran into this exact problem when they built LLM-powered subtitle translation for their platform. The translations themselves were excellent: fluent, natural, and often indistinguishable from human work. However, the product experience was broken because subtitles kept disappearing mid-playback, and the root cause turned out to be the AI’s own competence.

In this article, we will look at how the Vimeo engineering team overcame this problem and the decisions it made

Disclaimer: This post is based on publicly shared details from the Vimeo Engineering Team. Please comment if you notice any inaccuracies.

A subtitle file is a sequence of timed slots. Each slot has a start time, an end time, and a piece of text. The video player reads these slots and displays text during each window. Outside that window, nothing shows. If a slot is empty, the screen goes blank for that duration.

This means subtitle translation carries an implicit contract that must be followed. If the source language has four lines, the translation also needs to produce exactly four lines. Each translated line maps to the same time slot as the original. Breaking this contract results in empty slots.

LLMs break this contract by default because they’re optimized for fluency. When an LLM encounters messy, but natural human speech (filler words, false starts, repeated phrases), it does what a good translator would do. It cleans things up and merges fragmented thoughts into a single, polished sentence.

Here’s a concrete example. A speaker in a video says:

“Um, you know, I think that we’re gonna get... we’re gonna remove a lot of barriers.”

That maps to two timed subtitle slots on the video timeline. A traditional translation system handles each line separately, one-to-one. But the LLM recognizes this as a single, fragmented thought and produces one clean Japanese sentence, which is grammatically perfect and semantically accurate. But now the system has two time slots and only one line of text. The second slot goes blank, which means that the subtitles disappear while the speaker keeps talking.

Vimeo calls this the blank screen bug. And it isn’t a rare edge case. It’s the default behavior of any sufficiently capable language model translating messy human speech.

See the picture below:

If you’ve ever built anything that sends LLM output into a system expecting predictable structure (JSON schemas, form fields, database rows), you’ve probably hit a version of this same tension. The model optimizes for quality, and quality doesn’t always respect the structural contract your system depends on.

This problem gets significantly worse when you move beyond European languages.

Different languages don’t just use different words. They organize thoughts in fundamentally different orders and densities. Vimeo’s engineering team started calling this “the geometry of language,” and it essentially signifies that the shape of a sentence changes across languages in ways that make one-to-one line mapping structurally impossible in some cases.

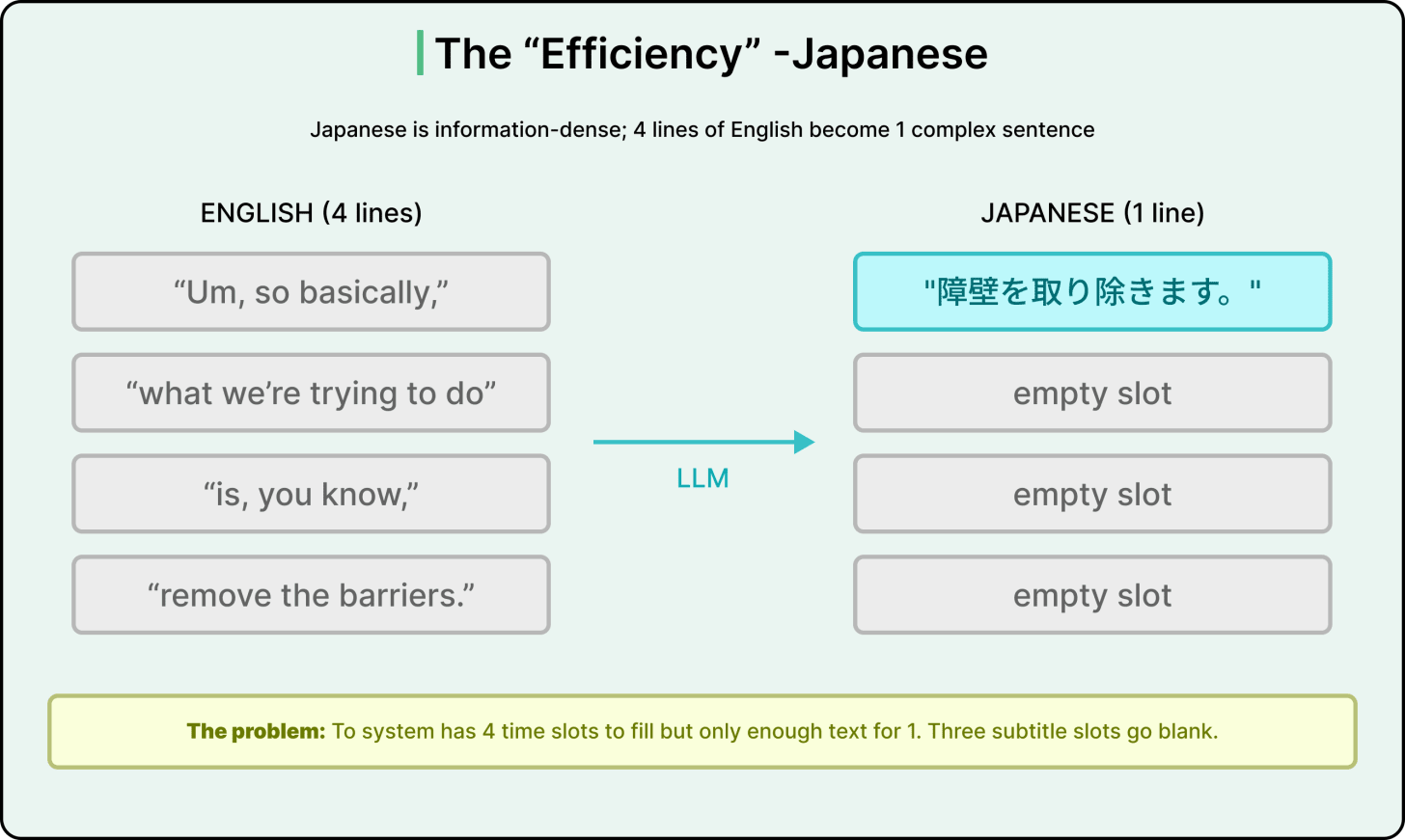

For example, Japanese is far more information-dense than English. Where an English speaker might speak four lines of filler (”Um, so basically,” / “what we’re trying to do” / “is, you know,” / “remove the barriers”), a typical Japanese translation consolidates all of that into a single, grammatically tight sentence.

See the example below:

The LLM is doing the right thing linguistically. Four lines of English filler genuinely are one thought in Japanese. But the subtitle system now has four time slots and enough text for one. Three slots go blank while the speaker keeps talking.

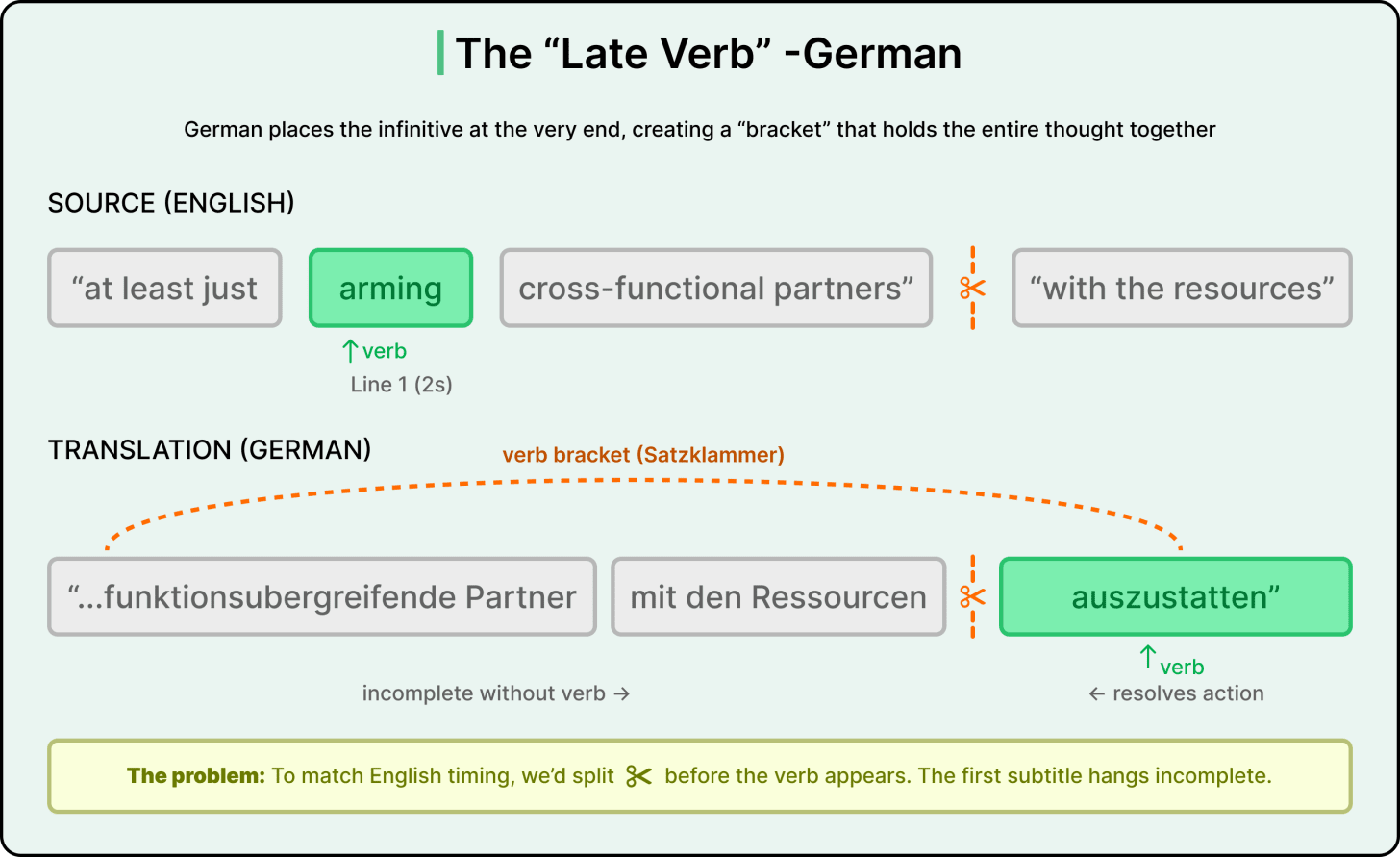

The German language has a different problem. German places verbs at the end of clauses, creating what linguists call a “verb bracket.” If the subtitle system tries to split a German sentence at a line boundary, the first subtitle hangs grammatically incomplete, missing its verb. The LLM resists producing this because it looks like a syntax error.

Each of these is a structurally different failure mode. The LLM is succeeding at translation while failing at structure. These are two fundamentally different jobs being crammed into a single prompt, and that realization led Vimeo to rethink its architecture.

Vimeo tried the obvious approach first.

One LLM prompt that translates the text and preserves the line count. In their words, it was “a losing battle.”

The creative requirement (fluency) was constantly fighting the structural requirement (timing). Asking the model to produce natural-sounding German while also splitting it at exact line boundaries means optimizing for two competing goals at once.

Even research backs this up. A 2024 study by Tam et al. found that imposing format constraints on LLMs measurably degrades their reasoning quality. Stricter constraints often mean worse performance. In other words, you’re not just asking the model to do two things. You’re making it worse at both.

So Vimeo stopped trying to do it all in one pass. They split the pipeline into three phases.

Before any translation happens, the system groups source lines into logical thought blocks of roughly 3-5 lines.

If we feed the LLM a single isolated line like “arming the partners,” it has zero context. It doesn’t know who is being armed or why. Feed it the entire transcript, and it loses track of where it is and starts hallucinating, meaning it generates plausible-sounding content that wasn’t in the original. The chunking algorithm scans for sentence boundaries and groups text so the LLM always sees a complete thought before translating.

Each chunk goes to the LLM with one instruction: translate for meaning. There is no line count enforcement and no structural constraints. The model is free to handle German verb brackets naturally, reorder Hindi syntax correctly, and compress Japanese efficiently. Linguistic quality is the only goal.

The fluent translated block goes into a second, separate LLM call with a completely different job. This call is purely structural.

The prompt essentially says: “Here are the original four English lines with timestamps. Here is the translated block. Break it back into four lines that match the source rhythm.” There is no concern for meaning, but only line count.

By separating these concerns, each pass gets to do its job without compromise. Phase 2 ensures the translation is grammatically sound. Phase 3 ensures the timing is respected. And on the first pass through this pipeline, roughly 95% of chunks map perfectly.

Ninety-five percent is impressive. But Vimeo ships to millions of viewers across nine languages. That other five percent also matters a lot.

This is where Vimeo’s engineering philosophy gets interesting. They stopped asking “how do we make the LLM get it right the first time?” and started asking “what happens when it doesn’t?” That reframe shaped everything about how they built the production system.

When the line mapper returns a mismatch (say, one line of German when it asked for two), the system doesn’t give up. It enters a correction loop, retrying with explicit feedback about the error. The prompt tells the model what went wrong and asks it to try again. Often, the model finds a valid synonym or slightly less natural phrasing that respects the line count. This correction loop resolves about a third of failures.

If that doesn’t work, the system escalates to a simpler LLM prompt. It strips away all the semantic instructions and gives the model a bare-bones task: “Here’s one block of text. Split it into exactly N lines.”

And if the LLM still can’t produce the right count, Vimeo stops asking models entirely. A rule-based algorithm takes over. Empty lines get filled with the last valid content. Too few lines get padded by duplicating text. Too many lines get truncated. The output in these edge cases is functional rather than perfect. You might see the same phrase repeated across a couple of subtitle slots. But every time slot gets filled, and the viewer never sees a blank screen.

This graduated fallback is what separates a production system from a demo. Vimeo’s data showed that the correction loop resolves about 32% of the failures that make it past the first pass. The rule-based splitter catches everything else. The result is 100% of chunks reach the user in a valid state.

This architecture works. But it carries real costs.

The multi-pass approach adds roughly 4-8% more processing time and 6-10% more token cost compared to a single-call translation. Vimeo argues this tradeoff pays for itself by eliminating around 20 hours of manual QA per 1,000 videos. At their scale, the math works clearly. At a smaller scale, it might not.

There’s also an uncomfortable quality gap across languages. The system ensures every language gets functional subtitles, but speakers of structurally different languages hit the fallback chain far more often than Spanish or Italian speakers. That means more repeated phrases, more slightly awkward line splits. The system guarantees no blank screens, but it doesn’t guarantee equal quality.

And there’s a genuine product question embedded in the rule-based fallback. When the system repeats a phrase across two subtitle slots to avoid a blank screen, is that actually a better viewer experience? Vimeo decided it is. That’s a reasonable product call, but it’s worth recognizing as a decision, not a technical inevitability.

The broader value of Vimeo’s experience reaches well beyond video subtitles. If you’re building AI into any product with structural constraints, their journey points to three principles that can be understood:

First, separate the creative work from the structural work. Asking one LLM call to be both brilliant and obedient means optimizing for competing goals, and research suggests that makes it worse at both.

Second, build your fallback chain before you build your happy path. The question isn’t how to prevent failures. It’s what your system does when they happen.

Third, accept that smarter models need smarter infrastructure around them. A simple word-for-word translator would never break subtitle sync. Intelligence is what creates the engineering challenge. Vimeo calls this the “infrastructure tax of intelligence,” and it’s a cost worth understanding before you build.

References:

2026-03-10 23:31:17

When trying to spin up AI agents, companies often get stuck in the prompting weeds and end up with agents that don’t deliver dependable results. This ebook from You.com goes beyond the prompt, revealing five stages for building a successful AI agent and why most organizations haven’t gotten there yet.

In this guide, you’ll learn:

Why prompts alone aren’t enough and how context and metadata unlock reliable agent automation

Four essential ways to calculate ROI, plus when and how to use each metric

If you’re ready to go beyond the prompt, this is the ebook for you.

For years, Airbnb supported credit and debit cards as the primary way guests could pay for accommodations.

However, today Airbnb operates in over 220 countries worldwide, and while cards work well in many regions, just relying on this payment approach excludes millions of potential users. In countries where credit card penetration is low or where people strongly prefer local payment methods, Airbnb was losing bookings and limiting its growth potential.

To solve this problem, the Airbnb Engineering Team launched the “Pay as a Local” initiative. The goal was to integrate 20+ locally preferred payment methods across multiple markets in just 14 months.

In this article, we will look at the technical architecture and engineering decisions that made this expansion possible.

Disclaimer: This post is based on publicly shared details from the Airbnb Engineering Team. Please comment if you notice any inaccuracies.

Local Payment Methods, or LPMs, extend beyond traditional payment cards. They include digital wallets like Naver Pay in South Korea and M-Pesa in Kenya, online bank transfers used across Europe, instant payment systems like PIX in Brazil and UPI in India, and regional payment schemes like EFTPOS and Cartes Bancaires.

Supporting LPMs provides several advantages.

First, offering familiar payment options increases conversion rates at checkout.

Second, it unlocks markets where credit card usage is minimal or nonexistent.

Third, it improves accessibility for guests who lack credit cards or traditional banking access.

The Airbnb team identified over 300 unique payment methods worldwide through initial research. For the first phase, they used a qualification framework to narrow this list. They evaluated the top 75 travel markets, selected the top one or two payment methods per market, excluded methods without clear travel use cases, and arrived at a shortlist of just over 20 LPMs suited for integration.

Before building support for LPMs, Airbnb needed to modernize its payment infrastructure.

The original system was monolithic, meaning all payment logic existed in one large codebase. This architecture created several problems:

Adding new features took considerable time, and time to market for new capabilities was measured in months.

Different teams couldn’t work independently.

The system was difficult to scale.

Airbnb implemented a multi-year replatforming initiative called Payments LTA, where LTA stands for Long-Term Architecture. The team shifted from a monolithic system to a capability-oriented services system structured by domains. This approach uses domain-driven decomposition, where the system is broken into smaller services based on business capabilities.

See the diagram below that shows a sample domain-driven approach:

After the entire exercise, the core payment domain at Airbnb consisted of multiple subdomains:

The Pay-in subdomain handles guest payments.

The Payout subdomain manages host payments.

Transaction Fulfillment oversees the complete transaction lifecycle.

The Processing subdomain integrates with third-party payment service providers.

Wallet and Instruments for stored payment methods.

Ledger for recording transactions.

Incentives and Stored Value for credits and coupons.

Issuing for creating payment instruments.

Settlement and Reconciliation for ensuring accurate money flows.

This modernization approach reduced time to market for new features, increased code reusability and extensibility, and empowered greater team autonomy by allowing teams to work on specific domains independently.

With AI generating ~80% of code, production systems are getting harder to debug with every deployment. Investigating issues requires following a trail of breadcrumbs across code, infrastructure, telemetry, and documents.

Teams are keeping up with production at scale using AI agents that investigate like senior engineers, forming hypotheses, running queries across systems, and converging on root cause with evidence.

Engineering teams at Coinbase and DoorDash are using Resolve AI to cut incident investigation time by 70%+.

Explore how AI agents help investigate issues in this interactive demo.

The Processing subdomain became particularly important for LPM integration.

Airbnb adopted a connector and plugin-based architecture for onboarding new payment service providers, or PSPs.

During replatforming, the team introduced Multi-Step Transactions, abbreviated as MST. This processor-agnostic framework supports payment flows completed across multiple stages.

For example, traditional card payments happen in a single step where you enter your card details and receive an immediate response. However, many local payment methods require multiple steps, such as redirecting to another website, authenticating with a separate app, or scanning a QR code.

MST defines a PSP-agnostic transaction language to describe the intermediate steps required in a payment. These steps are called Actions. Common action types include redirects to external websites or apps, strong customer authentication frictions like security challenges and fingerprinting, and payment method-specific flows unique to each LPM.

When a PSP indicates that an additional user action is required, its vendor plugin normalizes the request into an ActionPayload and returns it with a transaction intent status of ACTION_REQUIRED. This architecture ensures consistent handling of complex, multi-step payment experiences across diverse PSPs and markets.

Here is an example of what an ActionPayload looks like in JSON format:

{

“actionPayload”: {

“actionType”: “redirect”,

“actionParameters”: {

“redirectUrl”: “https://pspvendor1...”,

“method”: “GET”

}

}

}Source: Airbnb Engineering Blog

While the modernized payment platform laid the foundation for enabling LPMs, these payment methods introduced unique challenges.

For example, many local methods require users to complete transactions in third-party wallet apps, introducing complexity in app switching, session handoff, and synchronization between Airbnb and external digital wallets. Each local payment vendor also exposes different APIs and behaviors across charge, refund, and settlement flows.

The Airbnb team analyzed the end-to-end behavior of their 20+ LPMs and identified three foundational payment flows that capture the full spectrum of user and system interactions.

The first is the redirect flow. In this pattern, guests are redirected to a third-party site or app to complete the payment, then return to Airbnb to finalize their booking. Examples include Naver Pay, GoPay, and FPX. The process works as follows:

Airbnb’s payments platform sends a charge request to the local payment vendor

The vendor’s response includes a redirectUrl

The platform redirects the user to the external app or website

The user completes the payment

The user is redirected back to Airbnb with a result token

Airbnb’s payments platform uses this token to confirm and finalize the payment securely

The second is the async flow, where “async” stands for asynchronous. Guests complete payment externally after receiving a prompt, such as a QR code or push notification. Airbnb receives payment confirmation asynchronously via webhooks. Examples include PIX, MB Way, and Blik. The process works as follows:

Airbnb’s payments platform sends a charge request to the local payment vendor.

The vendor’s response includes QR code data.

The checkout page displays the QR code for the user to scan.

The user completes the payment in their wallet app.

After payment succeeds, the vendor sends a webhook notification to Airbnb.

The platform updates the payment status and confirms the order.

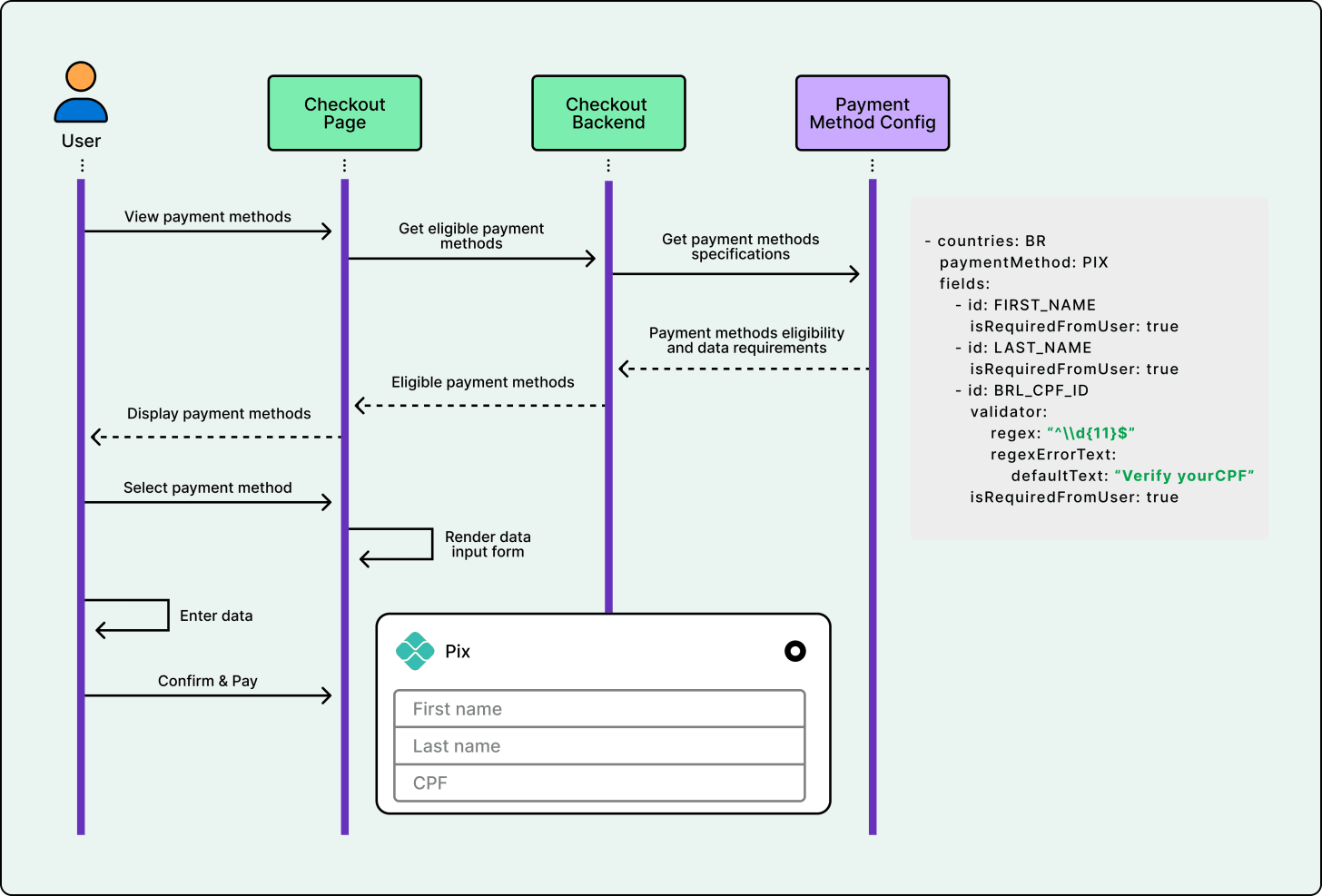

See the diagram below:

The third is the direct flow.

Guests enter their payment credentials directly within Airbnb’s interface, allowing real-time processing similar to traditional card payments. Examples include Carte Bancaires and Apple Pay.

Airbnb embraced a config-driven approach powered by a central YAML-based Payment Method Config.

This file acts as a single source of truth for flows, eligibility rules, input fields, refund rules, and other critical details. Instead of scattering payment method logic across frontend code, backend services, and various other systems, the team consolidated all relevant details in this config.

Both core payment services and frontend experiences reference this single source of truth. This ensures consistency for eligibility checks, UI rendering, and business rules. The unified approach dramatically reduces duplication, manual updates, and errors across the technology stack.

See the diagram below:

These configs also drive automated code generation for backend services. Using code generation tools, the system produces Java classes, DTOs (Data Transfer Objects), enums, database schemas, and integration scaffolding. As a result, integrating or updating a payment method becomes largely declarative. You simply make a config change rather than writing extensive new code. This streamlines launches from months to weeks and makes ongoing maintenance far simpler.

The payment widget is the payment method UI embedded into the checkout page. It includes the list of available payment methods and handles user inputs. Local payment methods often require specialized input forms and have unique country and currency eligibility requirements.

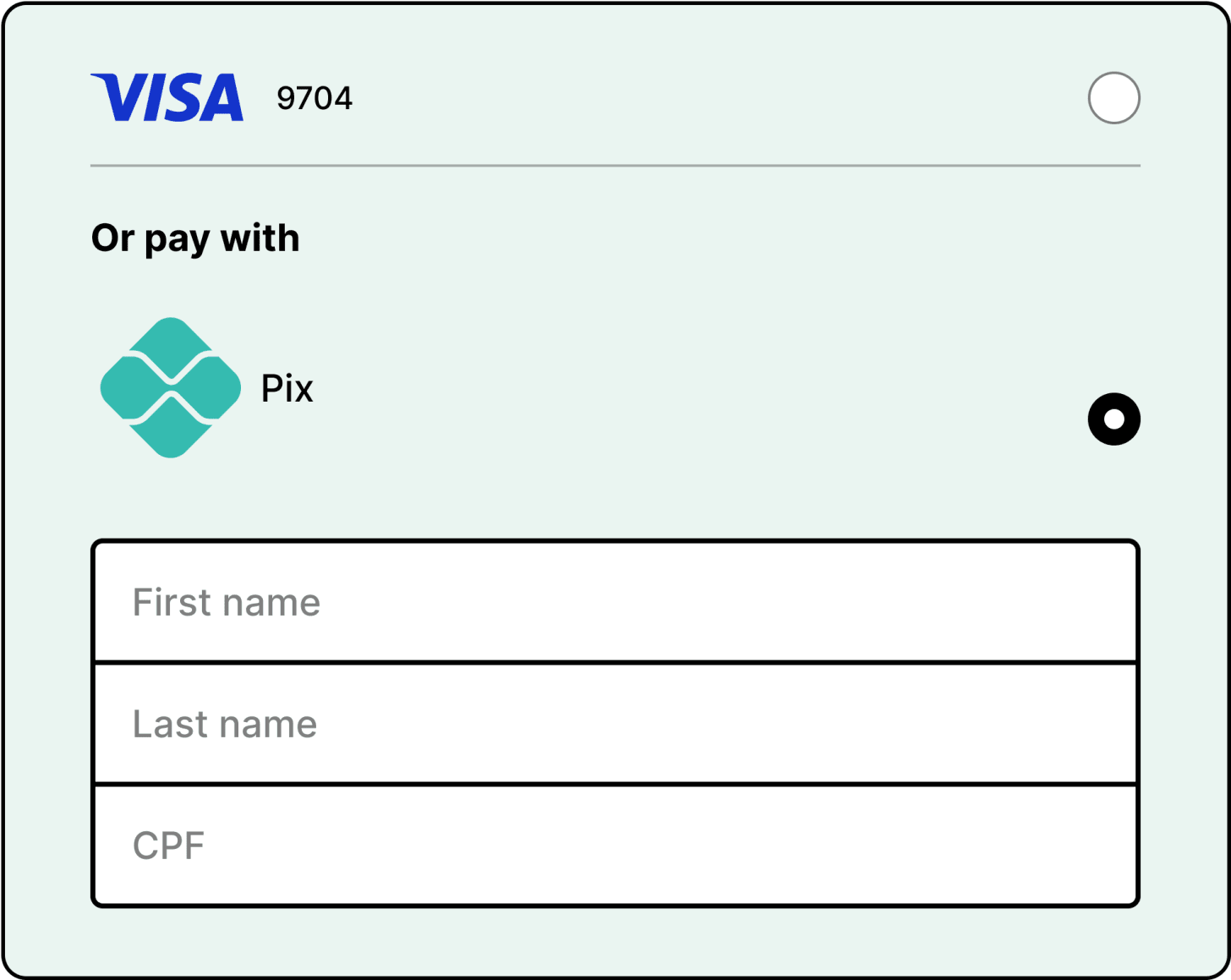

For example, PIX in Brazil requires the guest’s first name, last name, and CPF, which is the Brazilian tax identification number. Rather than hardcoding forms and rules into the client applications, Airbnb centralizes both form field specification and eligibility checks in the backend.

Servers send configuration payloads to clients, defining exactly which fields to collect, which validation rules to apply, and which payment options to render. This empowers the frontend to dynamically adapt UI and validation for each payment method. Teams can accelerate launches and keep user experiences current without requiring frequent client releases.

See the diagram below:

Testing local payment methods presents unique challenges.

Developers often don’t have access to local wallets. For example, a developer in the United States cannot easily test PIX, which requires a Brazilian bank account. Yet with such a broad range of payment methods and complex flows, comprehensive testing is essential to prevent regressions and ensure seamless functionality.

To address this challenge, Airbnb enhanced its in-house Payment Service Provider Emulator. See the diagram below:

This tool enables realistic simulation of PSP interactions for both redirect and asynchronous payment methods. The Emulator allows developers to test end-to-end payment scenarios without relying on unstable or nonexistent PSP sandboxes.

For redirect payments, the Emulator provides a simple UI mirroring PSP acquirer pages. Testers can explicitly approve or decline transactions for precise scenario control. For async methods, it returns QR code details and automatically schedules webhook emission tasks upon receiving a payment request. This delivers a complete, reliable testing environment across diverse LPMs.

Maintaining high reliability and availability is critical for Airbnb’s global payment system.

As the team expanded to support many new local payment methods, they faced increasing complexity. There were greater dependencies on external PSPs and wide variations in payment behaviors. A real-time card payment and a redirect flow like Naver Pay follow completely different technical paths.

Without proper visibility, regressions can go unnoticed until they affect real users. As dozens of new LPMs went live, observability became the foundation of reliability. Airbnb built a centralized monitoring framework that unifies metrics across all layers, from client to PSP.

When launching a new LPM, onboarding requires a single config change. Add the method name, and metrics begin streaming automatically. The system tracks four layers:

Client metrics showing user-level flow health from client applications

Payment backend metrics providing API-level metrics for payment flows

PSP metrics offering API-level visibility between Airbnb and the PSP

Webhook metrics tracking async completion status for redirect methods or refunds

Airbnb also standardized alerting rules across platform layers using composite alerts and anomaly detection. Each alert follows a consistent pattern with failure count, failure rate, and time window thresholds. An example alert might state: “Naver Pay resume failures greater than 5 and failure rate greater than 20% in 30 minutes.” This design minimizes false positives during low-traffic periods.

Two examples demonstrate the impact of this work.

Naver Pay is one of the fastest-growing digital payment methods in South Korea. As of early 2025, it reached over 30.6 million active users, representing approximately 60% of the South Korean population. Enabling Naver Pay delivered a more seamless and familiar payment experience for local guests while expanding Airbnb’s reach to new users who prefer Naver Pay as their primary payment method.

PIX is an instant payment system developed by the Central Bank of Brazil. By late 2024, more than 76% of Brazil’s population was using PIX, making it the country’s most popular payment method, surpassing cash, credit cards, and debit cards. In 2024 alone, PIX processed over 26.4 trillion Brazilian reals, approximately 4.6 trillion US dollars, in transaction volume. This underscores its pivotal role in Brazil’s digital payment ecosystem.

The Pay as a Local initiative delivered significant business and technical impact. Airbnb observed booking uplift and new user acquisition in markets where they launched local payment methods. Integration time was reduced through reusable flows and config-driven automation. Reliability improved through enhanced observability for early outage detection, standardized testing to prevent regressions, and streamlined vendor escalation and on-call processes for global resilience.

In other words, supporting local payment methods helps Airbnb remain competitive and relevant in the global travel industry. These payment options improve checkout conversion, drive adoption, and unlock new growth opportunities.

References:

2026-03-09 23:31:31

Agents are smarter when they can search the web - but with SerpApi, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel. SerpApi gives your AI applications clean, structured web data from major search engines and marketplaces, so your agents can research, verify, and answer with confidence.

Access real-time data with a simple API.

The AI open-source ecosystem has entered an extraordinary growth phase.

GitHub’s Octoverse 2025 report revealed that over 4.3 million AI-related repositories now exist on the platform, a 178% year-over-year jump in LLM-focused projects alone. In this environment, a select group of repositories has emerged as clear frontrunners, each amassing tens or even hundreds of thousands of stars by offering developers the tools to build autonomous agents, deploy models locally, and streamline AI-powered workflows.

Let’s look at the most impactful AI repositories trending on GitHub right now, covering what they do, why they matter, and how they fit into the broader AI landscape.

OpenClaw is the breakout star of 2026 and arguably the fastest-growing open-source project in GitHub history.

Created by PSPDFKit founder Peter Steinberger, it surged from 9,000 to over 60,000 stars in just a few days after going viral in late January 2026, and has since blown past 210,000 stars. The project was originally named Clawdbot, then Moltbot, and finally settled on OpenClaw.

At its core, OpenClaw is a personal AI assistant that runs entirely on your own devices. It operates as a local gateway connecting AI models to over 50 integrations, including WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack, Discord, Signal, and iMessage. Unlike cloud-based assistants, your data never leaves your machine. The assistant is always on, capable of browsing the web, filling out forms, running shell commands, writing and executing code, and controlling smart home devices. What sets it apart from other AI tools is its ability to write its own new skills, effectively extending its own capabilities without manual intervention.

OpenClaw has found use across developer workflow automation, personal productivity management, web scraping, browser automation, and proactive scheduling. On February 14, 2026, Steinberger announced he would be joining OpenAI, and the project would transition to an open-source foundation. Security researchers have raised valid concerns about the broad permissions the agent requires to function, and the skill repository still lacks rigorous vetting for malicious submissions, so users should be mindful of these risks when configuring their instances.

n8n is an open-source workflow automation platform that combines a visual, no-code interface with the flexibility of custom code, now enhanced with native AI capabilities. It has over 400 integrations and a self-hosted, fair-code license. This gives technical teams full control over their automation pipelines and data.

The platform stands out due to its AI-native approach. Users can incorporate large language models directly into their workflows via LangChain integration. They can build custom AI agent automations alongside traditional API calls, data transformations, and conditional logic. This bridges the gap between conventional business automation tools and cutting-edge AI agent workflows. For enterprises with strict data governance requirements, the self-hosting option is particularly valuable.

Common applications include AI-driven email triage, automated content pipelines, customer support agent flows, data enrichment workflows, and multi-step AI processing chains.

In a landscape dominated by cloud API subscriptions, Ollama took the opposite approach. It is a lightweight framework written in Go for running and managing large language models entirely on your own hardware. No data is sent to external services, and the entire experience is designed to work offline.

Ollama provides simple commands to download, run, and serve models locally, supporting Llama, Mistral, Gemma, DeepSeek, and a growing list of others. It includes desktop apps for macOS and Windows, which means even non-developers can get started with local AI. Its partnerships to support open-weight models from major research labs drove a massive surge of interest.

The project has become the backbone of the local AI movement, enabling developers to experiment with and deploy LLMs in privacy-critical or cost-sensitive environments. It pairs quite well with tools like Open WebUI to create a fully self-hosted alternative to commercial AI chat products.

AI coding tools are fast, capable, and completely context-blind. Even with rules, skills, and MCP connections, they generate code that misses your conventions, ignores past decisions, and breaks patterns. You end up paying for that gap in rework and tokens.

Unblocked changes the economics.

It builds organizational context from your code, PR history, conversations, docs, and runtime signals. It maps relationships across systems, reconciles conflicting information, respects permissions, and surfaces what matters for the task at hand. Instead of guessing, agents operate with the same understanding as experienced engineers.

You can:

Generate plans, code, and reviews that reflect how your system actually works

Reduce costly retrieval loops and tool calls by providing better context up front

Spend less time correcting outputs for code that should have been right in the first place

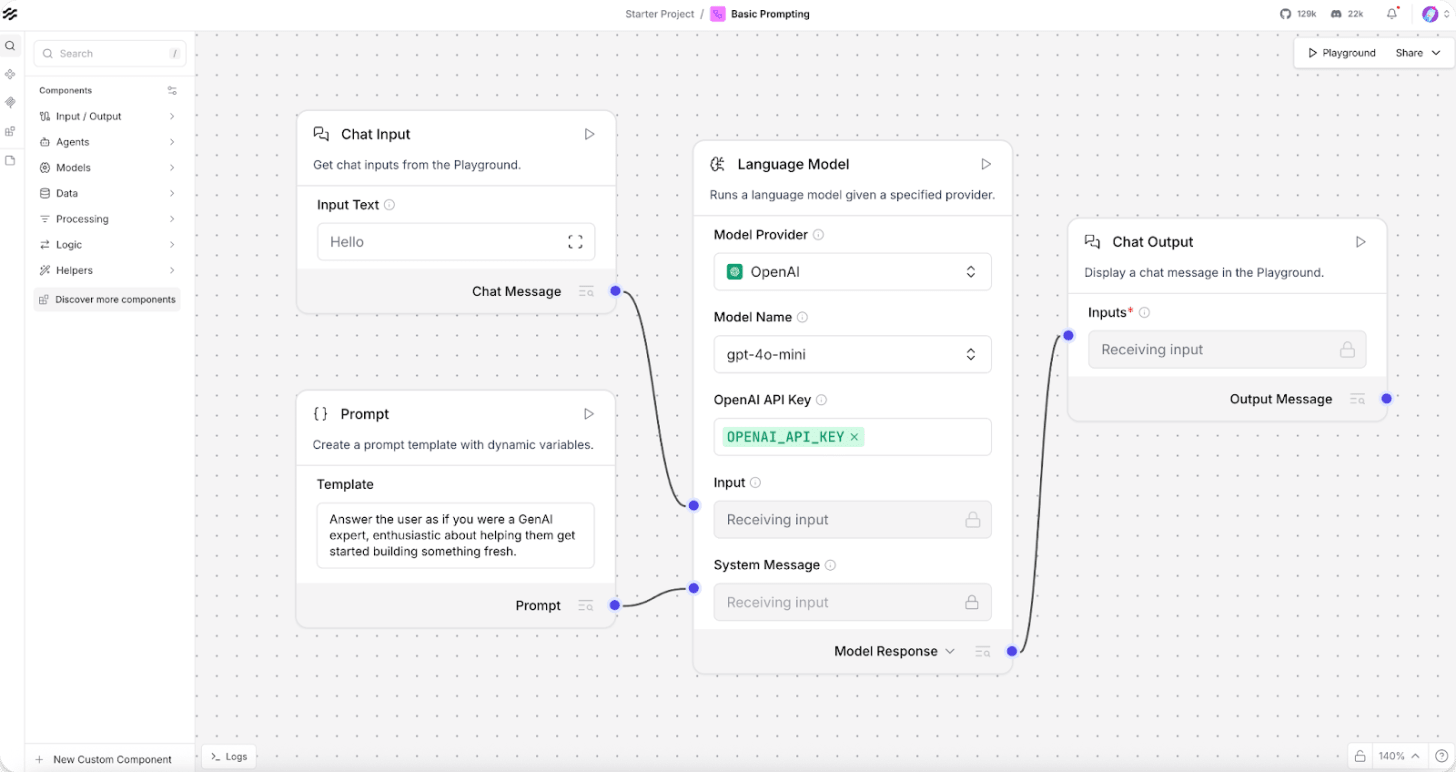

Langflow is a low-code platform for designing and deploying AI-powered agents and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) workflows, built on top of the LangChain framework. It provides a drag-and-drop interface for constructing chains of prompts, tools, memory modules, and data sources, with support for all major LLMs and vector databases.

Developers can visually orchestrate multi-agent conversations, manage memory and retrieval layers, and then deploy those flows as APIs or standalone applications. This eliminates the need for extensive backend engineering when prototyping complex AI pipelines. What used to take weeks of coding can often be assembled in an afternoon.

Langflow has attracted a significant community of data scientists and engineers. Its most common use cases include RAG pipeline prototyping, multi-agent conversation design, custom chatbot creation, and rapid LLM application development.

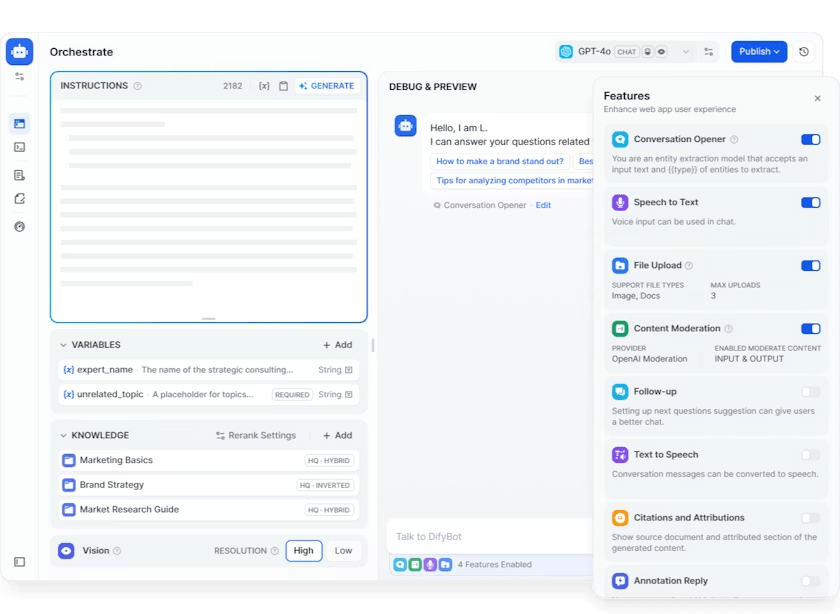

Dify is a production-ready platform for agentic workflow development, offering an all-in-one toolchain to build, deploy, and manage AI applications. Written primarily in TypeScript, it handles everything from enterprise QA bots to AI-driven custom assistants.

The platform includes a workflow builder for defining tool-using agents, built-in RAG pipeline management, support for multiple AI model providers, including OpenAI, Anthropic, and various open-source LLMs, usage monitoring, and both local and cloud deployment options. It also supports Model Context Protocol (MCP) integration. Dify handles the infrastructure boilerplate so teams can focus on crafting their agent logic.

Dify fills a crucial gap for teams that want to stand up AI-powered services quickly under an open-source, self-hostable framework. Its use cases span enterprise chatbot deployment, AI-powered internal tools, customer support automation, and multi-model orchestration

LangChain has cemented its position as the foundational framework for building reliable AI agents in Python. It provides modular components for chains, agents, memory, retrieval, tool use, and multi-agent orchestration. Its companion project, LangGraph, extends this further with support for complex, stateful agent workflows that include cycles and conditional branching.

Many of the other projects on this list build on top of LangChain or integrate with it directly, making it the connective tissue of the AI agent ecosystem. It has great support from Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, and every major model provider.

Developers use LangChain for building multi-agent systems, tool-using AI agents, RAG pipelines, conversational AI applications, and structured data extraction.

Open WebUI is a self-hosted AI platform designed to operate entirely offline, with over 282 million downloads and 124k+ stars. It provides a polished, ChatGPT-style web interface that connects to Ollama, OpenAI-compatible APIs, and other LLM runners, all installable from a single pip command.

The feature set is extensive. It includes a built-in inference engine for RAG, hands-free voice and video call capabilities with multiple speech-to-text and text-to-speech providers, a model builder for creating custom agents, native Python function calling, and persistent artifact storage. For enterprise users, it offers SSO, role-based access control, and audit logs. A community marketplace of prompts, tools, and functions makes extending the platform straightforward.

If Ollama provides the engine for running local models, Open WebUI provides the interface. Together, they form a popular self-hosted AI stack. Its primary use cases include private ChatGPT replacements, multi-model comparison setups, team AI platforms, and RAG-powered document question-answering systems.

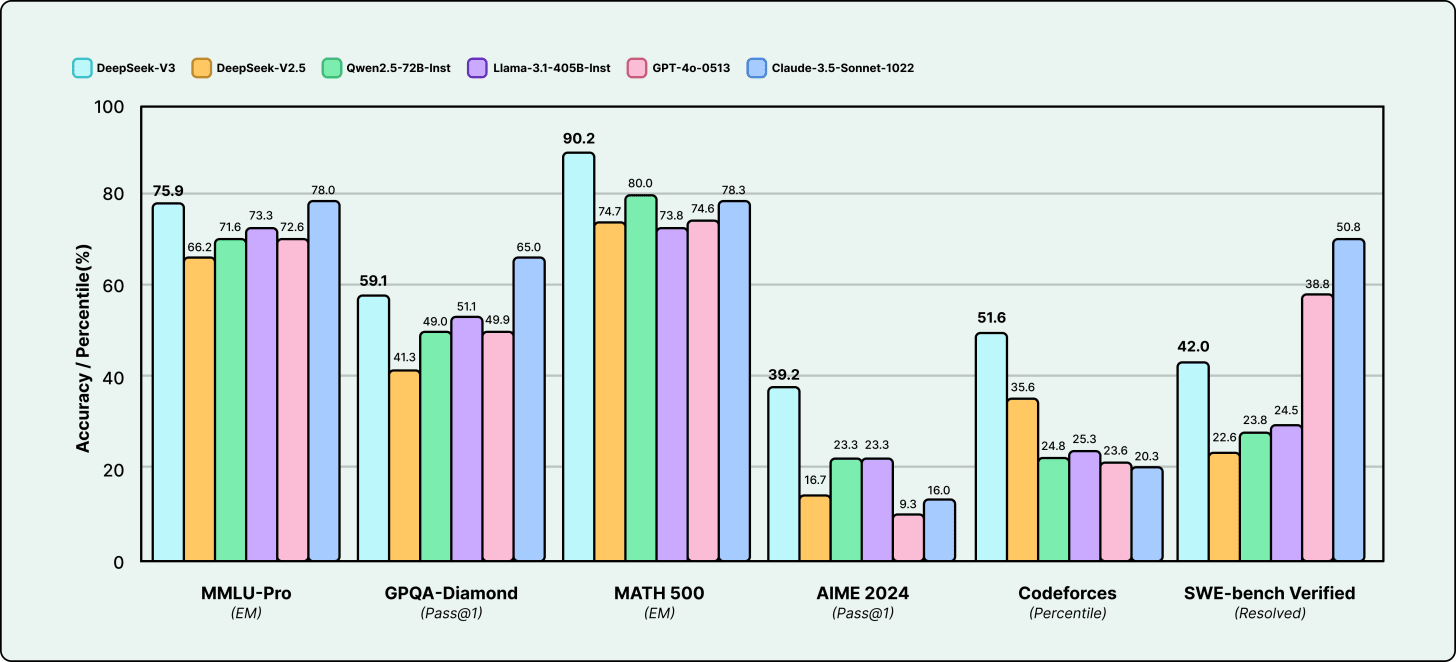

DeepSeek-V3 stunned the AI community by delivering benchmark results that rival frontier closed models like GPT-4, as a fully open-weight release.

Built on a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture, it is optimized for general-purpose reasoning and supports ultra-long 128K token contexts. The team introduced novel training techniques, including distilled reasoning chains, that set new standards in the open model community.

DeepSeek-V3 proved that the open-source community can produce models competitive with the best proprietary offerings. This has significant implications for developers who want high-capability AI without vendor lock-in, recurring API costs, or data privacy concerns. The model is available for free commercial use and can be fine-tuned for domain-specific applications. It runs locally via Ollama and has become a popular choice for powering custom AI agents and enterprise chatbots.

Gemini CLI is Google’s open-source contribution to the agentic coding space, bringing the Gemini multimodal model directly into developers’ terminals.

With a simple npx command, developers can chat with, instruct, and automate tasks using the Gemini model from the command line. It supports code assistance, natural language queries, integration with Google Cloud services, and can be embedded into scripts and CI/CD pipelines.

Basically, the tool abstracts away the complexity of API integration, making frontier AI capabilities immediately accessible from any terminal environment. Common uses include AI-assisted coding, command-line automation, batch file processing, and rapid prototyping.

RAGFlow is an open-source retrieval-augmented generation engine that combines advanced RAG techniques with agentic capabilities to create a robust context layer for LLMs.

The platform provides an end-to-end framework covering document ingestion, vector indexing, query planning, and tool-using agents that can invoke external APIs beyond simple text retrieval. It also supports citation tracking and multi-step reasoning, which are critical for enterprise applications where answer traceability matters.

As organizations move beyond basic chatbots toward production AI systems, RAGFlow addresses the hardest challenge: making AI answers grounded, traceable, and reliable. With 70k+ stars, it has become a key infrastructure component for enterprise knowledge bases, compliance-focused AI, research assistants, and multi-source data analysis workflows [10].

Claude Code is Anthropic’s agentic coding tool that operates from the terminal. Once installed, it understands the full codebase context and executes developer commands via natural language. You can ask it to refactor functions, explain files, generate unit tests, handle git operations, and carry out complex multi-file changes, all guided by conversation.

Claude Code distinguishes itself from simpler code completion tools via its ability to reason about an entire project, execute multi-step tasks, and maintain context across long coding sessions. It operates as an AI pair programmer that is deeply aware of your project structure and can act on code independently.

Its primary applications include full-codebase refactoring, automated test generation, code review and explanation, and git workflow automation.

Some common trends are shaping this landscape:

Ollama, Open WebUI, and OpenClaw collectively signal a massive shift: developers want to run AI on their own hardware.

Privacy concerns, API costs, and the desire for deep customization are driving this movement. The infrastructure for self-hosted AI has matured to the point where a single command can spin up a full-featured AI platform.

Nearly every repository on this list incorporates some form of autonomous agent behavior.

We have moved from AI that responds to AI that acts. Agents can now browse the web, execute code, manage files, orchestrate multi-step workflows, and even improve their own capabilities, all running continuously on your machine.

DeepSeek-V3’s success proved that open-weight models can compete with the best proprietary offerings.

Combined with efficient local runtimes like Ollama, this means developers can build high-capability applications without any API dependency. This trend is reshaping the economics of AI development fundamentally.

Langflow, Dify, and n8n show that drag-and-drop visual interfaces are becoming the preferred way to design AI agent pipelines.

This means domain experts, not just ML engineers, can create sophisticated AI applications. The barrier to entry for building production AI has never been lower.

The repositories profiled here are more than trending projects. They are the building blocks of a new AI infrastructure stack.

For developers, the takeaway is clear. Whether you are building an AI-powered product, automating internal workflows, or experimenting with frontier models, the tools in this list represent the most battle-tested, community-validated starting points available. Keep them on your radar. The pace of innovation in this space shows no signs of slowing down.

References:

OpenClaw - github.com/openclaw/openclaw

n8n - github.com/n8n-io/n8n

Ollama - github.com/ollama/ollama

Langflow - github.com/langflow-ai/langflow

Dify - github.com/langgenius/dify

LangChain - github.com/langchain-ai/langchain

Open WebUI - github.com/open-webui/open-webui

DeepSeek-V3 - github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-V3

Google Gemini CLI - github.com/google-gemini/gemini-cli

RAGFlow - github.com/infiniflow/ragflow

Claude Code - github.com/anthropics/claude-code

2026-03-08 00:31:24

If slow QA processes bottleneck you or your software engineering team and you’re releasing slower because of it — you need to check out QA Wolf.

QA Wolf’s AI-native service supports web and mobile apps, delivering 80% automated test coverage in weeks and helping teams ship 5x faster by reducing QA cycles to minutes.

QA Wolf takes testing off your plate. They can get you:

Unlimited parallel test runs for mobile and web apps

24-hour maintenance and on-demand test creation

Human-verified bug reports sent directly to your team

Zero flakes guarantee

The benefit? No more manual E2E testing. No more slow QA cycles. No more bugs reaching production.

With QA Wolf, Drata’s team of 80+ engineers achieved 4x more test cases and 86% faster QA cycles.

This week’s system design refresher:

CPU vs GPU vs TPU

How OAuth 2 Works

How Distributed Tracing Works at the High Level?

How GPUs Work at a High Level

Top 4 API Gateway Use Cases

Why does the same code run fast on a GPU, slow on a CPU, and leave both behind on a TPU? The answer is architecture. CPUs, GPUs, and TPUs are designed for different workloads.

CPU (Central Processing Unit): The CPU handles general-purpose computing. It's built for low latency and complex control flow, branching logic, system calls, interrupts, and decision-heavy code.

Operating systems, databases, and most applications run on the CPU because they need that flexibility.

GPU (Graphics Processing Unit): GPUs work differently. Instead of a few cores, they spread the work across thousands of cores that execute the same instruction across huge datasets (SIMT/SIMD-style).

If your workload is repetitive like matrix math, pixel shading, tensor operations, GPUs handle it quickly.

TPU (Tensor Processing Unit): TPUs are specialized hardware. The architecture is designed around matrix multiplication using systolic arrays, with compiler-controlled dataflow and on-chip buffers for weights and activations.

They are fast at neural network training and inference, as long as the workload fits the hardware well.

Over to you: When designing systems today, how do you decide what runs on CPU vs GPU vs specialized accelerators?

Authorization Code Flow (+ PKCE) - for user login:

User requests a protected resource

Server redirects to the Authorization Server (IdP)

Client generates a code_verifier and code_challenge (PKCE)

User authenticates and gives consent

IdP returns an authorization code

Server exchanges the code (with the verifier) for tokens

Server validates tokens and creates a session

PKCE prevents intercepted authorization codes from being reused. That’s why it’s the modern default for web and mobile apps.

Client Credentials Flow - for service-to-service:

A service requests an access token

The IdP authenticates the client

It issues a token

The service calls the API using a Bearer token

No user. Just machine identity.

Services generate telemetry data (traces, logs, metrics) as they handle requests.

The OpenTelemetry Collector receives this data from all services in a unified format.

The collector splits the data into three streams: traces, logs, and metrics.

Each stream is sent to a Receive & Process unit that prepares it for storage and analysis.

Processed data is stored in a Log Database for querying and long-term access.

Data from the database is visualized through a Visualization dashboard for monitoring and debugging.

Over to you: What else will you add to better understand distributed tracing?

When people say GPUs are powerful, what they really mean is this: GPUs are built for massive parallelism from the ground up.

Let’s break down what’s happening under the hood.

At the top level, a GPU chip is made up of many Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs). Think of SMs as mini parallel engines replicated across the chip. Instead of one big brain, you get dozens of smaller ones working simultaneously.

Inside each SM:

A Warp Scheduler decides which group of threads (a warp) runs next.

Dozens of CUDA Cores execute instructions in parallel.

A Register File stores thread-local data at ultra-low latency.

Load/Store units move data between registers and memory.

Texture units handle specialized memory operations.

L1 Cache provides fast, on-SM data access.

Each SM works independently, but they’re connected through an on-chip interconnect. Below that sits the L2 Cache, shared across all SMs. This is the coordination layer. If one SM misses in L1, it checks L2 before going to global memory.

Then come the Memory Controllers, which interface with Global Memory. This is where things get interesting:

Extremely high bandwidth

Much higher latency than on-chip memory

That’s why GPUs rely on massive parallelism. While some threads wait on memory, thousands of others keep executing.

An API Gateway sits between your clients and your services, and it does a lot more than just routing. Here are four use cases where it actually matters:

Handling Traffic Spikes: Without rate limiting, one misbehaving client can take down your entire system. The API Gateway enforces rate limits based on policies you define, such as per user, per IP, per subscription tier and so on. Exceed the limit? You get a 429 Too Many Requests.

Your backend services never even see that traffic. They stay healthy while the gateway takes the hit.

Securing Public APIs: Every request hits the gateway first. It checks the bearer token, validates it against the Identity Provider (IdP), and makes the access decision right there. No need to duplicate auth logic across every microservice. The gateway handles AuthN and AuthZ in one place.

Reducing Client-Server Roundtrips: A dashboard page might need user data, order history, and payment info. Without a gateway, the client makes three separate calls. With request aggregation, the client sends one GET /dashboard request. The gateway fans out to user-service, order-service, and payment-service internally, then combines everything into a single JSON response back to the client.

Supporting Multiple Clients: Web and mobile apps don't need the same data. A web client might call GET /v2/home and get a rich payload with full details. A mobile client hits GET /v1/home and gets a lighter response that doesn't burn through data.

The gateway handles versioning and payload transformation so your backend services don't need to know which client is calling.

Over to you: Are you running an API gateway in production? What's the biggest win it gave you?

2026-03-06 00:30:58

When we build software systems, one of the most important goals is making sure they can handle large amounts of work efficiently.

High-throughput systems are capable of processing vast quantities of data or transactions in a given timeframe. Throughput refers to the amount of work a system completes in a specific time period. For example, a web server might process 10K requests per second, or a database might handle 50K transactions per minute. The higher the throughput, the more work gets done in the same amount of time.

Throughput is different from latency. Latency measures how long it takes to complete a single operation, from start to finish. While throughput measures the volume of operations the system handles over time. For example, a system can have low latency but low throughput if it processes each request quickly but can only handle a few at once. Conversely, a system might have high throughput but high latency if it processes many requests simultaneously, but each request takes longer to complete.

There is often a tradeoff between these two metrics. When we batch multiple operations together, we increase throughput because the system processes many items at once. However, this batching introduces waiting time for individual operations, which increases latency. Similarly, processing every request immediately reduces latency but may limit throughput if the system becomes overwhelmed.

In this article, we will go through the fundamental concepts and practical strategies for building systems that can handle high volumes of work without breaking down under pressure.