2026-02-14 03:08:34

Since the beginning of 2023, big tech has spent over $814 billion in capital expenditures, with a large portion of that going towards meeting the demands of AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic.

Big tech has spent big on GPUs, power infrastructure, and data center construction, using a variety of financing methods to do so, including (but not limited to) leasing. And the way they’re going about structuring these finance deals is growing increasingly bizarre.

I’m not merely talking about Meta’s curious arrangement for its facility in Louisiana, though that certainly raised some eyebrows. Last year, Morgan Stanley published a report that claimed hyperscalers were increasingly relying on finance leases to obtain the “powered shell” of a data center, rather than the more common method of operating leases.

The key difference here is that finance leases, unlike operating leases, are effectively long-term loans where the borrower is expected to retain ownership of the asset (whether that be a GPU or a building) at the end of the contract. Traditionally, these types of arrangements have been used to finance the bits of a data center that have a comparatively limited useful life — like computer hardware, which grows obsolete with time.

The spending to date is, as I’ve written about again and again, an astronomical amount of spending considering the lack of meaningful revenue from generative AI.

Even after a year straight of manufacturing consent for Claude Code as the be-all-end-all of software development resulted in putrid results for Anthropic — $4.5 billion of revenue and $5.2 billion of losses before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization according to The Information — with (per WIRED) Claude Code only accounting for around $1.1 billion in annualized revenue in December, or around $92 million in monthly revenue.

This was in a year where Anthropic raised a total of $16.5 billion (with $13 billion of that coming in September 2025), and it’s already working on raising another $25 billion. This might be because it promised to buy $21 billion of Google TPUs from Broadcom, or because Anthropic expects AI model training costs to cost over $100 billion in the next 3 years. And it just raised another $30 billion — albeit with the caveat that some of said $30 billion came from previously-announced funding agreements with Nvidia and Microsoft, though how much remains a mystery.

According to Anthropic’s new funding announcement, Claude Code’s run rate has grown to “over $2.5 billion” as of February 12 2026 — or around $208 million. Based on literally every bit of reporting about Anthropic, costs have likely spiked along with revenue, which hit $14 billion annualized ($1.16 billion in a month) as of that date.

I have my doubts, but let’s put them aside for now.

Anthropic is also in the midst of one of the most aggressive and dishonest public relations campaigns in history. While its Chief Commercial Officer Paul Smith told CNBC that it was “focused on growing revenue” rather than “spending money,” it’s currently making massive promises — tens of billions on Google Cloud, “$50 billion in American AI infrastructure,” and $30 billion on Azure. And despite Smith saying that Anthropic was less interested in “flashy headlines,” Chief Executive Dario Amodei has said, in the last three weeks, that “almost unimaginable power is potentially imminent,” that AI could replace all software engineers in the next 6-12 months, that AI may (it’s always fucking may) cause “unusually painful disruption to jobs,” and wrote a 19,000 word essay — I guess AI is coming for my job after all! — where he repeated his noxious line that “we will likely get a century of scientific and economic progress compressed in a decade.”

Yet arguably the most dishonest part is this word “training.” When you read “training,” you’re meant to think “oh, it’s training for something, this is an R&D cost,” when “training LLMs” is as consistent a cost as inference (the creation of the output) or any other kind of maintenance.

While most people know about pretraining — the shoving of large amounts of data into a model (this is a simplification I realize) — in reality a lot of the current spate of models use post-training, which covers everything from small tweaks to model behavior to full-blown reinforcement learning where experts reward or punish particular responses to prompts.

To be clear, all of this is well-known and documented, but the nomenclature of “training” suggests that it might stop one day, versus the truth: training costs are increasing dramatically, and “training” covers anything from training new models to bug fixes on existing ones. And, more fundamentally, it’s an ongoing cost — something that’s an essential and unavoidable cost of doing business.

Training is, for an AI lab like OpenAI and Anthropic, as common (and necessary) a cost as those associated with creating outputs (inference), yet it’s kept entirely out of gross margins:

Anthropic has previously projected gross margins above 70% by 2027, and OpenAI has projected gross margins of at least 70% by 2029, which would put them closer to the gross margins of publicly traded software and cloud firms. But both AI developers also spend a tremendous amount on renting servers to develop new models—training costs, which don’t factor into gross margins—making it more difficult to turn a net profit than it is for traditional software firms.

This is inherently deceptive. While one would argue that R&D is not considered in gross margins, training isn’t gross margins — yet gross margins generally include the raw materials necessary to build something, and training is absolutely part of the raw costs of running an AI model. Direct labor and parts are considered part of the calculation of gross margin, and spending on training — both the data and the process of training itself — are absolutely meaningful, and to leave them out is an act of deception.

Anthropic’s 2025 gross margins were 40% — or 38% if you include free users of Claude — on inference costs of $2.7 (or $2.79) billion, with training costs of around $4.1 billion. What happens if you add training costs into the equation?

Let’s work it out!

Training is not an up front cost, and considering it one only serves to help Anthropic cover for its wretched business model. Anthropic (like OpenAI) can never stop training, ever, and to pretend otherwise is misleading. This is not the cost just to “train new models” but to maintain current ones, build new products around them, and many other things that are direct, impossible-to-avoid components of COGS. They’re manufacturing costs, plain and simple.

Anthropic projects to spend $100 billion on training in the next three years, which suggests it will spend — proportional to its current costs — around $32 billion on inference in the same period, on top of $21 billion of TPU purchases, on top of $30 billion on Azure (I assume in that period?), on top of “tens of billions” on Google Cloud. When you actually add these numbers together (assuming “tens of billions” is $15 billion), that’s $200 billion.

Anthropic (per The Information’s reporting) tells investors it will make $18 billion in revenue in 2026 and $55 billion in 2027 — year-over-year increases of 400% and 305% respectively, and is already raising $25 billion after having just closed a $30bn deal. How does Anthropic pay its bills? Why does outlet after outlet print these fantastical numbers without doing the maths of “how does Anthropic actually get all this money?”

Because even with their ridiculous revenue projections, this company is still burning cash, and when you start to actually do the maths around anything in the AI industry, things become genuinely worrying.

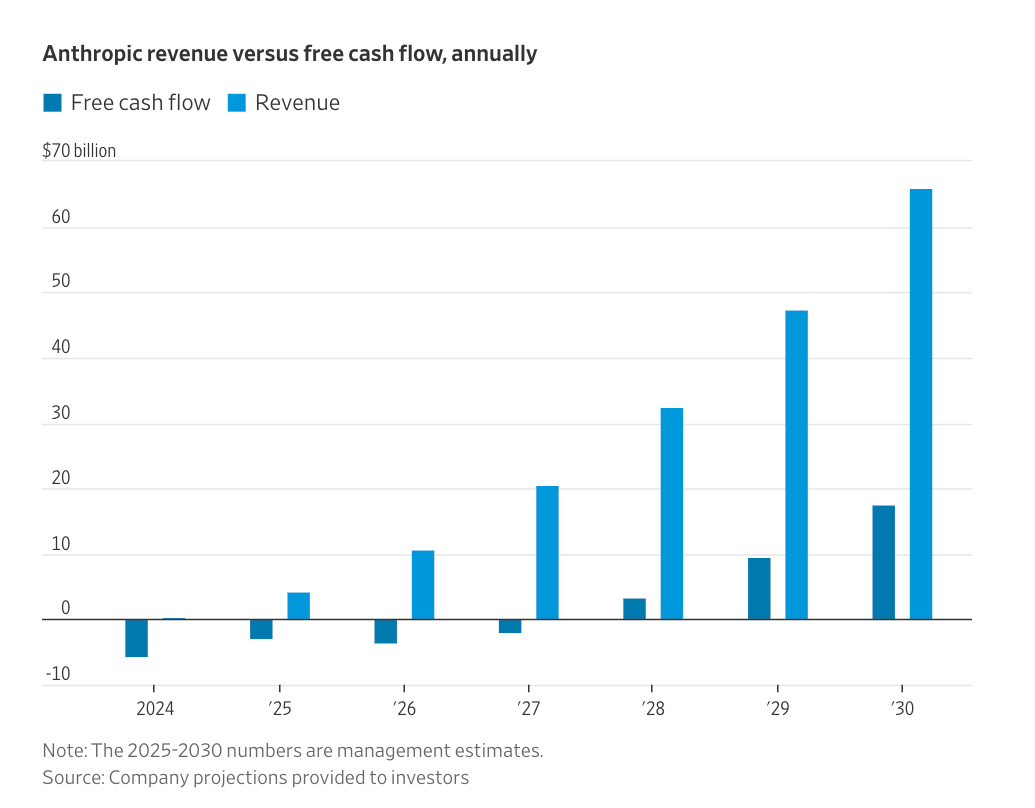

You see, every single generative AI company is unprofitable, and appears to be getting less profitable over time. Both The Information and Wall Street Journal reported the same bizarre statement in November — that Anthropic would “turn a profit more quickly than OpenAI,” with The Information saying Anthropic would be cash flow positive in 2027 and the Journal putting the date at 2028, only for The Information to report in January that 2028 was the more-realistic figure.

If you’re wondering how, the answer is “Anthropic will magically become cash flow positive in 2028”:

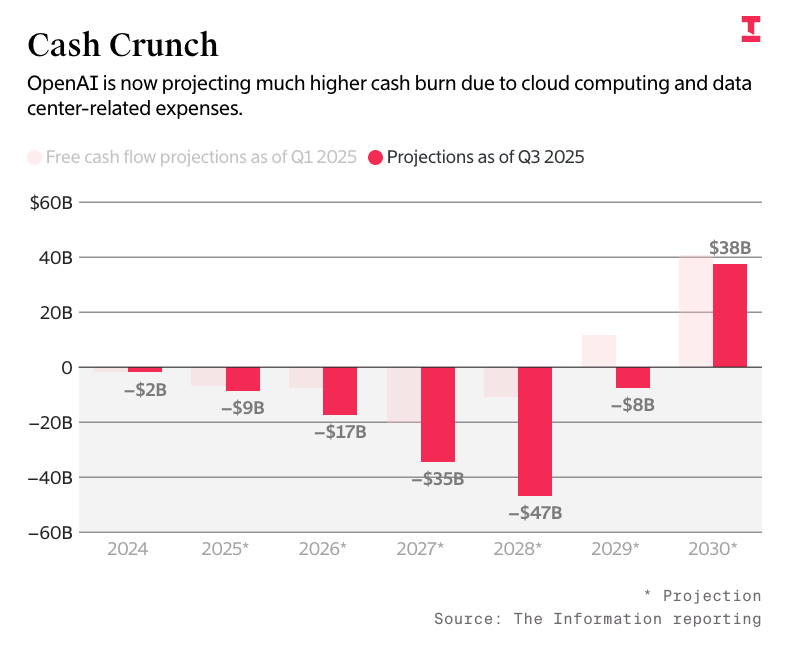

This is also the exact same logic as OpenAI, which will, per The Information in September, also, somehow, magically turn cashflow positive in 2030:

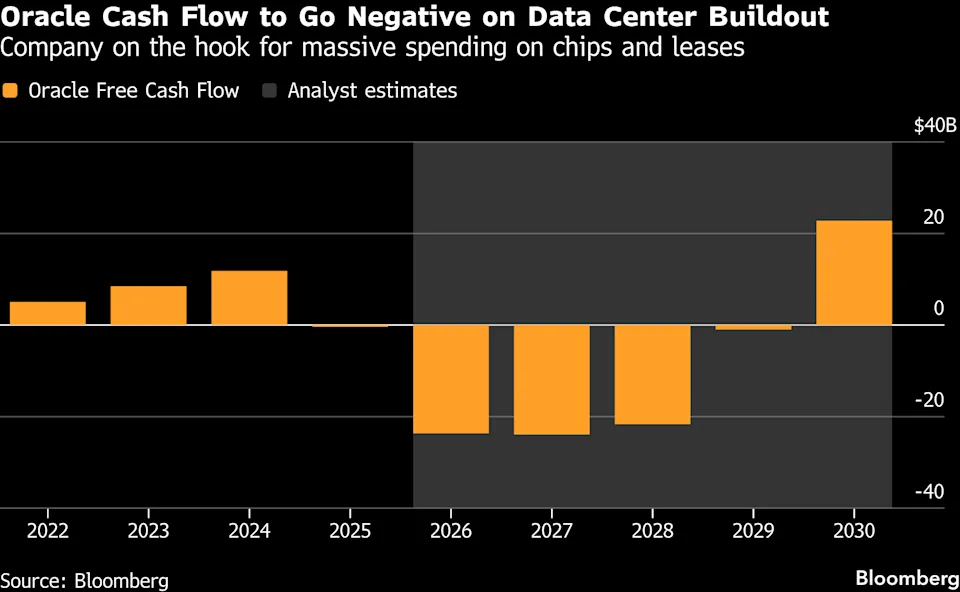

Oracle, which has a 5-year-long, $300 billion compute deal with OpenAI that it lacks the capacity to serve and that OpenAI lacks the cash to pay for, also appears to have the same magical plan to become cash flow positive in 2029:

Somehow, Oracle’s case is the most legit, in that theoretically at that time it would be done, I assume, paying the $38 billion it’s raising for Stargate Shackelford and Wisconsin, but said assumption also hinges on the idea that OpenAI finds $300 billion somehow.

it also relies upon Oracle raising more debt than it currently has — which, even before the AI hype cycle swept over the company, was a lot.

As I discussed a few weeks ago in the Hater’s Guide To Oracle, a megawatt of data center IT load generally costs (per Jerome Darling of TD Cowen) around $12-14m in construction (likely more due to skilled labor shortages, supply constraints and rising equipment prices) and $30m a megawatt in GPUs and associated hardware. In plain terms, Oracle (and its associated partners) need around $189 billion to build the 4.5GW of Stargate capacity to make the revenue from the OpenAI deal, meaning that it needs around another $100 billion once it raises $50 billion in combined debt, bonds, and printing new shares by the end of 2026.

I will admit I feel a little crazy writing this all out, because it’s somehow a fringe belief to do the very basic maths and say “hey, Oracle doesn’t have the capacity and OpenAI doesn’t have the money.” In fact, nobody seems to want to really talk about the cost of AI, because it’s much easier to say “I’m not a numbers person” or “they’ll work it out.”

This is why in today’s newsletter I am going to lay out the stark reality of the AI bubble, and debut a model I’ve created to measure the actual, real costs of an AI data center.

While my methodology is complex, my conclusions are simple: running AI data centers is, even when you remove the debt required to stand up these data centers, a mediocre business that is vulnerable to basically any change in circumstances.

Based on hours of discussions with data center professionals, analysts and economists, I have calculated that in most cases, the average AI data center has gross margins of somewhere between 30% and 40% — margins that decay rapidly for every day, week, or month that you take putting a data center into operation.

This is why Oracle has negative 100% margins on NVIDIA’s GB200 chips — because the burdensome up-front cost of building AI data centers (as GPUs, servers, and other associated) leaves you billions of dollars in the hole before you even start serving compute, after which you’re left to contend with taxes, depreciation, financing, and the cost of actually powering the hardware.

Yet things sour further when you face the actual financial realities of these deals — and the debt associated with them.

Based on my current model of the 1GW Stargate Abilene data center, Oracle likely plans to make around $11 billion in revenue a year from the 1.2GW (or around 880MW of critical IT). While that sounds good, when you add things like depreciation, electricity, colocation costs of $1 billion a year from Crusoe, opex, and the myriad of other costs, its margins sit at a stinkerific 27.2% — and that’s assuming OpenAI actually pays, on time, in a reliable way.

Things only get worse when you factor in the cost of debt. While Oracle has funded Abilene using a mixture of bonds and existing cashflow, it very clearly has yet to receive the majority of the $25 billion+ in GPUs and associated hardware (with only 96,000 GPUs “delivered”), meaning that it likely bought them out of its $18 billion bond sale from last September.

If we assume that maths, this means that Oracle is paying a little less than $963 million a year (per the terms of the bond sale) whether or not a single GPU is even turned on, leaving us with a net margin of 22.19%... and this is assuming OpenAI pays every single bill, every single time, and there are absolutely no delays.

These delays are also very, very expensive. Based on my model, if we assume that 100MW of critical IT load is operational (roughly two buildings and 100,000 GB200s) but has yet to start generating revenue, Oracle is burning, without depreciation (EDITOR’S NOTE: sorry! This previously said depreciation was a cash expense and was included in this number (even though it wasn’t!), but it's correct in the model!), around $4.69 million a day in cash. I have also confirmed with sources in Abilene that there is no chance that Stargate Abilene is fully operational in 2026.

In simpler terms:

I will admit I’m quite disappointed that the media at large has mostly ignored this story. Limp, cautious “are we in an AI bubble?” conversations are insufficient to deal with the potential for collapse we’re facing.

Today, I’m going to dig into the reality of the costs of AI, and explain in gruesome detail exactly how easily these data centers can rapidly approach insolvency in the event that their tenants fail to pay.

The chain of pain is real:

These GPUs are purchased, for the most part, using debt provided by banks or financial institutions. While hyperscalers can and do fund GPUs using cashflow, even they have started to turn to debt.

At that point, the company that bought the GPUs sinks hundreds of millions of dollars to build a data center, and once it turns on, provides compute to a model provider, which then begins losing money selling access to those GPUs. For example, both OpenAI and Anthropic lose billions of dollars, and both rely on venture capital to fund their ability to continue paying for accessing those GPUs.

At that point, OpenAI and Anthropic offer either subscriptions — which cost far more to offer than the revenue they provide — or API access to their models on a per-million-token basis. AI startups pay to access these models to run their services, which end up costing more than the revenue they make, which means they have to raise venture capital to continue paying to access those models.

Outside of hyperscalers paying NVIDIA for GPUs out of cashflow, none of the AI industry is fueled by revenue. Every single part of the industry is fueled by some kind of subsidy.

As a result, the AI bubble is really a stress test of the global venture capital, private equity, private credit, institutional and banking system, and its willingness to fund all of this forever, because there isn't a single generative AI company that's got a path to profitability.

Today I’m going to explain how easily it breaks.

2026-02-07 01:34:14

Have you ever looked at something too long and felt like you were sort of seeing through it? Has anybody actually looked at a company this much in a way that wasn’t some sort of obsequious profile of a person who worked there? I don’t mean this as a way to fish for compliments — this experience is just so peculiar, because when you look at them hard enough, you begin to wonder why everybody isn’t just screaming all the time.

Yet I really do enjoy it. When you push aside all the marketing and the interviews and all that and stare at what a company actually does and what its users and employees say, you really get a feel of the guts of a company. I’m enjoying it. The Hater’s Guides are a lot of fun, and I’m learning all sorts of things about the ways in which companies try to hide their nasty little accidents and proclivities.

Today, I focus on one of the largest.

In the last year I’ve spoken to over a hundred different tech workers, and the ones I hear most consistently from are the current and former victims of Microsoft, a company with a culture in decline, in large part thanks to its obsession with AI. Every single person I talk to about this company has venom on their tongue, whether they’re a regular user of Microsoft Teams or somebody who was unfortunate to work at the company any time in the last decade.

Microsoft exists as a kind of dark presence over business software and digital infrastructure. You inevitably have to interact with one of its products — maybe it’s because somebody you work with uses Teams, maybe it’s because you’re forced to use SharePoint, or perhaps you’re suffering at the hands of PowerBI — because Microsoft is the king of software sales. It exists entirely to seep into the veins of an organization and force every computer to use Microsoft 365, or sit on effectively every PC you use, forcing you to interact with some sort of branded content every time you open your start menu.

This is a direct results of the aggressive monopolies that Microsoft built over effectively every aspect of using the computer, starting by throwing its weight around in the 80s to crowd out potential competitors to MS-DOS and eventually moving into everything including cloud compute, cloud storage, business analytics, video editing, and console gaming, and I’m barely a third through the list of products.

Microsoft uses its money to move into new markets, uses aggressive sales to build long-term contracts with organizations, and then lets its products fester until it’s forced to make them better before everybody leaves, with the best example being the recent performance-focused move to “rebuild trust in Windows” in response to the upcoming launch of Valve’s competitor to the Xbox (and Windows gaming in general), the Steam Machine.

Microsoft is a company known for two things: scale and mediocrity. It’s everywhere, its products range from “okay” to “annoying,” and virtually every one of its products is a clone of something else.

And nowhere is that mediocrity more obvious than in its CEO.

Since taking over in 2014, CEO Satya Nadella has steered this company out of the darkness caused by aggressive possible chair-thrower Steve Ballmer, transforming from the evils of stack ranking to encouraging a “growth mindset” where you “believe your most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work.” Workers are encouraged to be “learn-it-alls” rather than “know-it-alls,” all part of a weird cult-like pseudo-psychology that doesn’t really ring true if you actually work at the company.

Nadella sells himself as a calm, thoughtful and peaceful man, yet in reality he’s one of the most merciless layoff hogs in known history. He laid off 18,000 people in 2014 months after becoming CEO, 7,800 people in 2015, 4,700 people in 2016, 3,000 people in 2017, “hundreds” of people in 2018, took a break in 2019, every single one of the workers in its physical stores in 2020 along with everybody who worked at MSN, took a break in 2021, 1,000 people in 2022, 16,000 people in 2023, 15,000 people in 2024 and 15,000 people in 2025.

Despite calling for a “referendum on capitalism” in 2020 and suggesting companies “grade themselves” on the wider economic benefits they bring to society, Nadella has overseen an historic surge in Microsoft’s revenues — from around $83 billion a year when he joined in 2014 to around $300 billion on a trailing 12-month basis — while acting in a way that’s callously indifferent to both employees and customers alike.

At the same time, Nadella has overseen Microsoft’s transformation from an asset-light software monopolist that most customers barely tolerate to an asset-heavy behemoth that feeds its own margins into GPUs that only lose it money. And it’s that transformation that is starting to concern investors, and raises the question of whether Microsoft is heading towards a painful crash.

You see, Microsoft is currently trying to pull a fast one on everybody, claiming that its investments in AI are somehow paying off despite the fact that it stopped reporting AI revenue in the first quarter of 2025. In reality, the one segment where it would matter — Microsoft Azure, Microsoft’s cloud platform where the actual AI services are sold — is stagnant, all while Redmond funnels virtually every dollar of revenue directly into more GPUs.

Intelligent Cloud also represents around 40% of Microsoft’s total revenue, and has done so consistently since FY2022. Azure sits within Microsoft's Intelligent Cloud segment, along with server products and enterprise support.

For the sake of clarity, here’s how Microsoft describes Intelligent Cloud in its latest end-of-year K-10 filing:

Our Intelligent Cloud segment consists of our public, private, and hybrid server products and cloud services that power modern business and developers. This segment primarily comprises:

It’s a big, diverse thing — and Microsoft doesn’t really break things down further from here — but Microsoft makes it clear in several places that Azure is the main revenue driver in this fairly diverse business segment.

Some bright spark is going to tell me that Microsoft said it has 15 million paid 365 Copilot subscribers (which, I add, sits under its Productivity and Business Processes segment), with reporters specifically saying these were corporate seats, a fact I dispute, because this is the quote from Microsoft’s latest conference call around earnings:

We saw accelerating seat growth quarter-over-quarter and now have 15 million paid Microsoft 365 Copilot seats, and multiples more enterprise Chat users.

At no point does Microsoft say “corporate seat” or “business seat.” “Enterprise Copilot Chat” is a free addition to multiple different Microsoft 365 products, and Microsoft 365 Copilot could also refer to Microsoft’s $18 to $21-a-month addition to Copilot Business, as well as Microsoft’s enterprise $30-a-month plans. And remember: Microsoft regularly does discounts through its resellers to bulk up these numbers.

As an aside: If you are anything to do with the design of Microsoft’s investor relations portal, you are a monster. Your site sucks. Forcing me to use your horrible version of Microsoft Word in a browser made this newsletter take way longer. Every time I want to find something on it I have to click a box and click find and wait for your terrible little web app to sleepily bumble through your 10-Ks.

If this is a deliberate attempt to make the process more arduous, know that no amount of encumbrance will stop me from going through your earnings statements, unless you have Satya Nadella read them. I’d rather drink hemlock than hear another minute of that man speak after his interview from Davos. He has an answer that’s five and a half minutes long that feels like sustaining a concussion.

When Nadella took over, Microsoft had around $11.7 billion in PP&E (property, plant, and equipment). A little over a decade later, that number has ballooned to $261 billion, with the vast majority added since 2020 (when Microsoft’s PP&E sat around $41 billion).

Also, as a reminder: Jensen Huang has made it clear that GPUs are going to be upgraded on a yearly cycle, guaranteeing that Microsoft’s armies of GPUs regularly hurtle toward obsolescence. Microsoft, like every big tech company, has played silly games with how it depreciates assets, extending the “useful life” of all GPUs so that they depreciate over six years, rather than four.

And while someone less acquainted with corporate accounting might assume that this move is a prudent, fiscally-conscious tactic to reduce spending by using assets for longer, and stretching the intervals between their replacements, in reality it’s a handy tactic to disguise the cost of Microsoft’s profligate spending on the balance sheet.

You might be forgiven for thinking that all of this investment was necessary to grow Azure, which is clearly the most important part of Microsoft’s Intelligent Cloud segment. In Q2 FY2020, Intelligent Cloud revenue sat at $11.9 billion on PP&E of around $40 billion, and as of Microsoft’s last quarter, Intelligent Cloud revenue sat at around $32.9 billion on PP&E that has increased by over 650%.

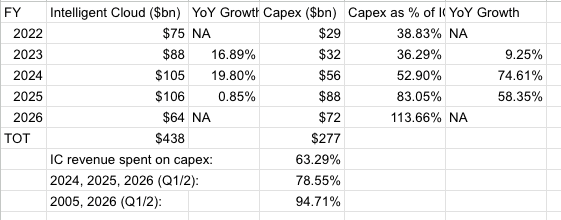

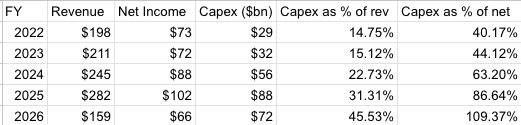

Good, right? Well, not really. Let’s compare Microsoft’s Intelligent Cloud revenue from the last five years:

In the last five years, Microsoft has gone from spending 38% of its Intelligent Cloud revenue on capex to nearly every penny (over 94%) of it in the last six quarters, at the same time in two and a half years that Intelligent Cloud has failed to show any growth.

An important note: If you look at Microsoft’s 2025 K-10, you’ll notice that it lists the Intelligent Cloud revenue for 2024 as $87.4bn — not, as the above image shows, $105bn.

If you look at the 2024 K-10, you’ll see that Intelligent Cloud revenues are, in fact, $105bn. So, what gives?

Essentially, before publishing the 2025 K-10, Microsoft decided to rejig which part of its operations fall into which particular segments, and as a result, it had to recalculate revenues for the previous year. Having read and re-read the K-10, I’m not fully certain which bits of the company were recast.

It does mention Microsoft 365, although I don’t see how that would fall under Intelligent Cloud — unless we’re talking about things like Sharepoint, perhaps. I’m at a loss. It’s incredibly strange.

Things, I’m afraid, get worse. Microsoft announced in July 2025 — the end of its 2025 fiscal year— that Azure made $75 billion in revenue in FY2025. This was, as the previous link notes, the first time that Microsoft actually broke down how much Azure actually made, having previously simply lumped it in with the rest of the Intelligent Cloud segment.

I’m not sure what to read from that, but it’s still not good. meaning that Microsoft spent every single penny of its Azure revenue from that fiscal year on capital expenditures of $88 billion and then some, a little under 117% of all Azure revenue to be precise. If we assume Azure regularly represents 71% of Intelligent Cloud revenue, Microsoft has been spending anywhere from half to three-quarters of Azure’s revenue on capex.

To simplify: Microsoft is spending lots of money to build out capacity on Microsoft Azure (as part of Intelligent Cloud), and growth of capex is massively outpacing the meager growth that it’s meant to be creating.

You know what’s also been growing? Microsoft’s depreciation charges, which grew from $2.7 billion in the beginning of 2023 to $9.1 billion in Q2 FY2026, though I will add that they dropped from $13 billion in Q1 FY2026, and if I’m honest, I have no idea why! Nevertheless, depreciation continues to erode Microsoft’s on-paper profits, growing (much like capex, as the two are connected!) at a much-faster rate than any investment in Azure or Intelligent Cloud.

But worry not, traveler! Microsoft “beat” on earnings last quarter, making a whopping $38.46 billion in net income…with $9.97 billion of that coming from recapitalizing its stake in OpenAI. Similarly, Microsoft has started bulking up its Remaining Performance Obligations. See if you can spot the difference between Q1 and Q2 FY26, emphasis mine:

Q1FY26:

Revenue allocated to remaining performance obligations, which includes unearned revenue and amounts that will be invoiced and recognized as revenue in future periods, was $398 billion as of September 30, 2025, of which $392 billion is related to the commercial portion of revenue. We expect to recognize approximately 40% of our total company remaining performance obligation revenue over the next 12 months and the remainder thereafter.

Q2FY26:

Revenue allocated to remaining performance obligations related to the commercial portion of revenue was $625 billion as of December 31, 2025, with a weighted average duration of approximately 2.5 years. We expect to recognize approximately 25% of both our total company remaining performance obligation revenue and commercial remaining performance obligation revenue over the next 12 months and the remainder thereafter

So, let’s just lay it out:

…Microsoft’s upcoming revenue dropped between quarters as every single expenditure increased, despite adding over $200 billion in revenue from OpenAI. A “weighted average duration” of 2.5 years somehow reduced Microsoft’s RPOs.

But let’s be fair and jump back to Q4 FY2025…

Revenue allocated to remaining performance obligations, which includes unearned revenue and amounts that will be invoiced and recognized as revenue in future periods, was $375 billion as of June 30, 2025, of which $368 billion is related to the commercial portion of revenue. We expect to recognize approximately 40% of our total company remaining performance obligation revenue over the next 12 months and the remainder thereafter.

40% of $375 billion is $150 billion. Q3 FY25? 40% on $321 billion, or $128.4 billion. Q2 FY25? $304 billion, 40%, or $121.6 billion.

It appears that Microsoft’s revenue is stagnating, even with the supposed additions of $250 billion in spend from OpenAI and $30 billion from Anthropic, the latter of which was announced in November but doesn’t appear to have manifested in these RPOs at all.

In simpler terms, OpenAI and Anthropic do not appear to be spending more as a result of any recent deals, and if they are, that money isn’t arriving for over a year.

Much like the rest of AI, every deal with these companies appears to be entirely on paper, likely because OpenAI will burn at least $115 billion by 2029, and Anthropic upwards of $30 billion by 2028, when it mysteriously becomes profitable two years before OpenAI “does so” in 2030.

These numbers are, of course, total bullshit. Neither company can afford even $20 billion of annual cloud spend, let alone multiple tens of billions a year, and that’s before you get to OpenAI’s $300 billion deal with Oracle that everybody has realized (as I did in September) requires Oracle to serve non-existent compute to OpenAI and be paid hundreds of billions of dollars that, helpfully, also don’t exist.

Yet for Microsoft, the problems are a little more existential.

Last year, I calculated that big tech needed $2 trillion in new revenue by 2030 or investments in AI were a loss, and if anything, I think I slightly underestimated the scale of the problem.

As of the end of its most recent fiscal quarter, Microsoft has spent $277 billion or so in capital expenditures since the beginning of FY2022, with the majority of them ($216 billion) happening since the beginning of FY2024. Capex has ballooned to the size of 45.5% of Microsoft’s FY26 revenue so far — and over 109% of its net income.

This is a fucking disaster. While net income is continuing to grow, it (much like every other financial metric) is being vastly outpaced by capital expenditures, none of which can be remotely tied to profits, as every sign suggests that generative AI only loses money.

While AI boosters will try and come up with complex explanations as to why this is somehow alright, Microsoft’s problem is fairly simple: it’s now spending 45% of its revenues to build out data centers filled with painfully expensive GPUs that do not appear to be significantly contributing to overall revenue, and appear to have negative margins.

Those same AI boosters will point at the growth of Intelligent Cloud as proof, so let’s do a thought experiment (even though they are wrong): if Intelligent Cloud’s segment growth is a result of AI compute, then the cost of revenue has vastly increased, and the only reason we’re not seeing it is that the increased costs are hitting depreciation first.

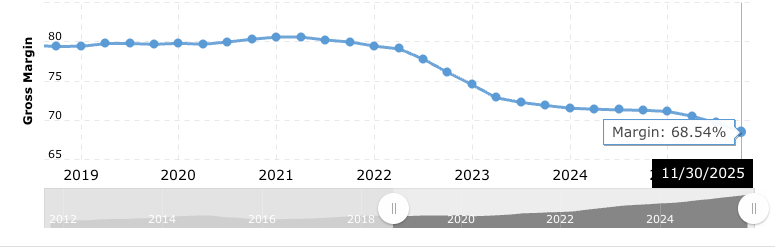

You see, Intelligent Cloud is stalling, and while it might be up by 8.8% on an annualized basis (if we assume each quarter of the year will be around $30 billion, that makes $120 billion, so about an 8.8% year-over-year increase from $106 billion), that’s come at the cost of a massive increase in capex (from $88 billion for FY2025 to $72 billion for the first two quarters of FY2026), and gross margins that have deteriorated from 69.89% in Q3 FY2024 to 68.59% in FY2026 Q2, and while operating margins are up, that’s likely due to Microsoft’s increasing use of contract workers and increased recruitment in cheaper labor markets.

And as I’ll reveal later, Microsoft has used OpenAI’s billions in inference spend to cover up the collapse of the growth of the Intelligent Cloud segment. OpenAI’s inference spend now represents around 10% of Azure’s revenue.

Microsoft, as I discussed a few weeks ago, is in a bind. It keeps buying GPUs, all while waiting for the GPUs it already has to start generating revenue, and every time a new GPU comes online, its depreciation balloons. Capex for GPUs began in seriousness in Q1 FY2023 following October’s shipments of NVIDIA’s H100 GPUs, with reports saying that Microsoft bought 150,000 H100s in 2023 (around $4 billion at $27,000 each) and 485,000 H100s in 2024 ($13 billion). These GPUs are yet to provide much meaningful revenue, let alone any kind of profit, with reports suggesting (based on Oracle leaks) that the gross margins of H100s are around 26% and A100s (an older generation launched in 2020) are 9%, for which the technical term is “dogshit.” Somewhere within that pile of capex also lies orders for H200 GPUs, and as of 2024, likely NVIDIA’s B100 (and maybe B200) Blackwell GPUs too.

You may also notice that those GPU expenses are only some portion of Microsoft’s capex, and the reason is because Microsoft spends billions on finance leases and construction costs. What this means in practical terms is that some of this money is going to GPUs that are obsolete in 6 years, some of it’s going to paying somebody else to lease physical space, and some of it is going into building a bunch of data centers that are only useful for putting GPUs in.

And none of this bullshit is really helping the bottom line! Microsoft’s More Personal Computing segment — including Windows, Xbox, Microsoft 365 Consumer, and Bing — has become an increasingly-smaller part of revenue, representing in the latest quarter a mere 17.64% of Microsoft’s revenue in FY26 so far, down from 30.25% a mere four years ago.

We are witnessing the consequences of hubris — those of a monopolist that chased out any real value creators from the organization, replacing them with an increasingly-annoying cadre of Business Idiots like career loser Jay Parikh and scummy, abusive timewaster Mustafa Suleyman.

Satya Nadella took over Microsoft with the intention of fixing its culture, only to replace the aggressive, loudmouthed Ballmer brand with a poisonous, passive aggressive business mantra of “you’ve always got to do more with less.”

Today, I’m going to walk you through the rotting halls of Redmond’s largest son, a bumbling conga line of different businesses that all work exactly as well as Microsoft can get away with.

Welcome to The Hater’s Guide To Microsoft, or Instilling The Oaf Mindset.

2026-01-31 01:23:06

You can’t avoid Oracle.

No, really, you can’t. Oracle is everywhere. It sells ERP software – enterprise resource planning, which is a rat king of different services for giant companies for financial services, procurement (IE: sourcing and organizing the goods your company needs to run), compliance, project management, and human resources. It sells database software, and even owns the programming language Java as part of its acquisition of Sun Microsystems back in 2010.

Its customers are fucking everyone: hospitals (such as England’s National Health Service), large corporations (like Microsoft), health insurance companies, Walmart, and multiple different governments. Even if you have never even heard of Oracle before, it’s almost entirely certain that your personal data is sitting in an Oracle-designed system somewhere.

Once you let Oracle into your house, it never leaves. Canceling contracts is difficult, to the point that one Redditor notes that some clients agreed to spend a minimum amount of money on services without realizing, meaning that you can’t remove services you don’t need even during the renewal of a contract. One user from three years ago told the story of adding two users to their contract for Oracle’s Netsuite Starter Edition (around $1000 a month in today’s pricing), only for an Oracle account manager to call a day later to demand they upgrade to the more expensive package ($2500 per month) for every user.

In a thread from a year ago, another user asked for help renegotiating their contract for Netsuite, adding that “[their] company is no where near the state needed to begin an implementation” and “would use a third party partner to implement” software that they had been sold by Oracle. One user responded by saying that Oracle would play hardball and “may even use [the] threat of attorneys.”

In fact, there are entire websites about negotiations with Oracle, with Palisade Compliance saying that “Oracle likes a frenetic pace where contracts are reviewed and dialogues happen under the constant pressure of Oracle’s quarter closes,” describing negotiations with them as “often rushed, filled with tension, and littered with threats from aggressive sales and Oracle auditing personnel.” This is something you can only do when you’ve made it so incredibly difficult to change providers. What’re you gonna do? Have your entire database not work? Pay up.

Oracle also likes to do “audits” of big customers where it makes sure that every single part of your organization that uses Oracle software is paying for it, or were not using it in a way that was not allowed based on their contract. For example, Oracle sued healthcare IT company Perry Johnson & Associates in 2020 because the company that built PJ&A’s database systems used Oracle’s database software. The case was settled.

This is all to say that Oracle is a big company that sells lots of stuff, and increases the pressure around its quarterly earnings as a means of boosting revenues. If you have a company with computers that might be running Java or Oracle’s software — even if somebody else installed it for you! — you’ll be paying Oracle, one way or another. They even tried to sue Google for using the open source version of Java to build its Android operating system (though they lost).

Oracle is a huge, inevitable pain in the ass, and, for the most part, an incredibly profitable one. Every time a new customer signs on at Oracle, they pledge themselves to the Graveyard Smash and permanent fealty to Larry Ellison’s database empire.

As a result, founder Larry Ellison has become one of the richest people in the world — the fifth-largest as of writing this sentence — owning 40% of Oracle’s stock and, per Martin Peers of The Information, will earn about $2.3 billion in dividends in the next year.

Oracle has also done well to stay out of bullshit hype-cycles. While it quickly spun up vague blockchain and metaverse offerings, its capex stayed relatively flat at around $1 billion to $2.1 billion a fiscal year (which runs from June 1 to May 31), until it burst to $4.511 in FY2022 (which began on June 1, 2021, for reference), $8.695 billion in FY2023, $6.86 billion in FY2024, and then increasing a teeny little bit to $21.25 billion in FY2025 as it stocked up on AI GPUs and started selling compute.

You may be wondering if that helped at all, and it doesn’t appear to have at all. Oracle’s net income has stayed in the $2 billion to $3 billion range for over a decade, other than a $2.7 billion spike last quarter from its sale of its shares in Ampere.

You see, things have gotten weird at Oracle, in part because of the weirdness of the Ellisons themselves, and their cozy relationship with the Trump Administration (and Trump itself). Ellison’s massive wealth backed son David Ellison’s acquisition of Paramount, putting conservative Bari Weiss at the helm of CBS in an attempt to placate and empower the right wing, and is currently trying to buy Warner Brothers Discovery (though it appears Netflix may have won), all in pursuit of kissing up to a regime steeped in brutality and bigotry that killed two people in Minnesota.

As part of the media blitz, the Ellisons also took part in the acquisition of TikTok, and last week established a joint venture that owns TikTok’s US operations, with Oracle owning 15% of the new company (along with VC Silverlake and the UAE’s MGXs fund). Per TechCrunch:

Oracle will serve as the trusted security partner, responsible for auditing and ensuring compliance with National Security Terms, according to a memo. The company already provides cloud services for TikTok and manages user data in the U.S. Notably, Oracle previously made a bid for TikTok back in 2020.

I know that you’re likely a little scared that an ultra right-wing billionaire has bought another major social network. I know you think that Oracle, a massive and inevitable cloud storage platform owned by a man who looks like H.R. Giger drew Jerry Stiller. I know you’re likely worried about a replay of the Elon Musk Twitter fiasco, where every week it seemed like things would collapse but it never seemed to happen, and then Musk bought an election.

What if I told you that things were very different, and far more existentially perilous for Oracle?

You see, Oracle is arguably one of the single-most evil and successful companies in the world, and it’s got there by being an aggressive vendor of database and ERP software, one that, like a tick with a law degree, cannot be removed without some degree of bloodshed. Perhaps not the highest-margin business in the world, but you know, it worked.

Oracle has stuck to the things it’s known for for years and years and done just fine…

…until AI, that is. Let’s see what AI has done for Oracle’s gross margi-OH MY GOD!

The scourge of AI GPUs has taken Oracle’s gross margin from around 79% in 2021 to 68.54% in 2025, with CNBC reporting that FactSet-polled analysts saw it falling to 49% by 2030, which I think is actually being a little optimistic.

Oracle was very early to high-performance computing, becoming the first cloud in the world to have general availability of NVIDIA’s A100 GPUs back in September 2020, and in June 2023 (at the beginning of Oracle’s FY2024), Ellison declared that Oracle would spend “billions” on NVIDIA GPUs, naming AI firm Cohere as one of its customers.

In May 2024, Musk and Ellison discussed a massive cloud compute contract — a multi-year, $10 billion deal that fell apart in July 2024 when Musk got impatient, a blow that was softened by Microsoft’s deal to buy compute capacity for OpenAI, for chips to be rented out of a data center in Abilene Texas that, about six months later, OpenAI would claim was part of a “$500 billion Stargate initiative” announcement between Oracle, SoftBank and OpenAI that was so rushed that Ellison had to borrow a coat to stay warm on the White House lawn, per The Information.

“Stargate” is commonly misunderstood as a Trump program, or something that has raised $500 billion, when what it actually is is Oracle raising debt to build data centers for OpenAI. Instead of staying in its lane as a dystopian datacenter mobster, Oracle entered into negative-to-extremely-low margin realm of GPU rentals, raising $58 billion in debt and signing $248 billion in data center leases to service a 5-year-long $300 billion contract with OpenAI that it doesn’t have the capacity for and OpenAI doesn’t have the money to pay for.

Oh, and TikTok? The billion-user social network that Oracle sort-of-just bought? There’s one little problem with it: per The Information, ByteDance investors estimate TikTok lost several billion dollars last year on revenues of roughly $20 billion, attributed to its high growth costs and, per The Information, “higher operational and labor costs in overseas markets compared to China.”

Now, I know what you’re gonna say: Ellison bought TikTok as a propaganda tool, much like Musk bought Twitter. “The plan isn’t for it to be profitable,” you say. “It’s all about control” you say, and I say, in response, that you should know exactly how fucked Oracle is.

In its last quarter, Oracle had negative $13 billion in cash flow, and between 2022 and late 2025 quintupled its PP&E (from $12.8 billion to $67.85 billion), primarily through the acquisition of GPUs for AI compute. Its remaining performance obligations are $523 billion, with $300 billion of that coming from OpenAI in a deal that starts, according to the Wall Street Journal, “in 2027,” with data centers that are so behind in construction that the best Oracle could muster is saying that 96,000 B200 GPUs had been “delivered” to the Stargate Abilene data center in December 2025 for a data center of 450,000 GPUs that has to be fully operational by the end of 2026 without fail.

And what’re the margins on those GPUs? Negative 100%.

Oracle, a business borne of soulless capitalist brutality, has tied itself existentially to not just the success of AI, but the specific, incredible, impossible success of OpenAI, which will have to muster up $30 billion in less than a year to start paying for it, and another $270 billion or more to pay for the rest…at a time when Oracle doesn’t have the capacity and has taken on brutal debt to build it. For Oracle to survive, OpenAI must find a way to pay it four times the annual revenue of Microsoft Azure ($75 billion), and because OpenAI burns billions of dollars, it’s going to have to raise all of that money at a time of historically low liquidity for venture capital.

Did I mention that Oracle took on $56 billion of debt to build data centers specifically for OpenAI? Or that the banks who invested in these deals don’t seem to be able to sell off the debt?

Let me put it really simply:

We are setting up for a very funny and chaotic situation where Oracle simply runs out of money, and in the process blows up Larry Ellison’s fortune. However much influence Ellison might have with the administration, Oracle has burdened itself with debt and $248 billion in data center lease obligations — costs that are inevitable, and are already crushing the life out of the company (and the stock).

The only way out is if OpenAI becomes literally the most-successful cash-generating company of all time within the next two years, and that’s being generous. This is not a joke. This is not an understatement. Sam Altman holds Larry Ellison’s future in his clammy little hands, and there isn’t really anything anybody can do about it other than hope for the best, because Oracle already took on all that debt and capex.

Forget about politics, forget about the fear in your heart that the darkness always wins, and join me in The Hater’s Guide To Oracle, or My Name’s Larry Ellison, and Welcome To Jackass.

2026-01-24 01:57:18

2026-01-17 01:15:37

Soundtrack - Radiohead - Karma Police

I just spent a week at the Consumer Electronics Show, and one word kept coming up: bullshit.

LG, a company known for making home appliances and televisions, demonstrated a robot (named “CLOiD” for some reason) that could “fold laundry” (extremely slowly, in limited circumstances, and even then it sometimes failed) or cook (by which I mean put things in an oven that opened automatically) or find your keys (in a video demo), one that it has no intention of releasing. The media generally gave it an easy go, with one reporter suggesting that a barely-functioning tech demo somehow “marked a turning point” because LG was now “entering the robotics space” with a product it had no intention of selling.

So, why did LG demo the robot? To con the media and investors, of course! Hundreds of other companies demoed other robots you couldn’t buy, and despite what reports might say, we were not shown “the future of robotics” in any meaningful sense. We got to see what happens when companies run out of ideas and can only copy each other. CES 2026 was the “year of robotics” in the same way that somebody is a sailor because they wore a captain’s hat while sitting in a cardboard box.

Yet the robotics companies were surprisingly ethical compared to the nonsensical tide of LLM-driven wank, from no-name dregs in the basement of the Venetian Expo Center to companies like Lenovo warbling about its “AI super agent.” In fact, fuck it, let’s talk about that.

“AI is evolving and getting new capabilities, sensing our three-dimensional world, understanding how things move and connect,” said Lenovo CEO Yang Yuanqing, leading into a demo of Lenovo Qira, before claiming it “redefines what it means to have technology built around you.” One would think the demo that follows would be an incredible demonstration of futuristic technology. Instead, a spokesperson walked up, asked Qira to show what it could see (IE: multimodal capabilities available for years in many models), received a summary of notifications (available in effectively any LLM integration, and incredibly prone to hallucinations), and asked “what to get her kids when she had some free time,” at which point Qira told her, and I quote, that “the Las Vegas Fashion Mall has some Labubus that children will go crazy for,” referring to the kind of tool-based web search that’s been available since 2024.

The presenter noted that Qira also can add reminders — something that has been available for years on most iOS or Android devices — and search for documents, then showed a proof-of-concept wearable that can record and transcribe meetings, a product that I saw no less than seven times during my time at CES.

Lenovo rented out the entirety of the Las Vegas Sphere to do a demonstration of a fucking chatbot powered by OpenAI’s models on Microsoft Azure, and everybody acted like it was something new. No, Qira is not a “big bet” on AI — it’s a fucking chatbot forced on anybody buying a Lenovo PC, full of features like “summarize this” or “transcribe this” or “tell me what’s on my calendar,” features peddled by business idiots that have little experience with any real-world applications of just about anything, marketed with the knowledge that the media will do the hard work of explaining why anybody should give a shit.

Want better-looking video or audio from your TV? Get fucked! You’re getting nano banana image generation from Google and other LLM features from Samsung

You can now generate images on your TV using Google’s Nano Banana model — a useless idea peddled by a company that doesn’t know what consumers actually want, varnished as making your TV-based assistant “more helpful and more visually engaging.” As David Katzmaier correctly said, nobody asked for LLMs in their TVs, allowing you to “click to search” something that’s on your TV, something that no normal person will do.

In fact, most of the show felt like companies doing madlibs with startup decks to try and trick people into thinking they’d done anything other than staple a frontend on top of a Large Language Model. Nowhere was that more obvious than the glut of useless AI-powered “smart” glasses, all of which claim to do translation, or dictation, or run “apps” using clunky, ugly and hard-to-use interfaces, all using the same LLMs, all doing effectively the same thing. These products only exist because Meta decided to blow several billion dollars on launching “AI glasses,” with the slew of copycats phrased as being “part of a new category” rather than “a bunch of companies making a bunch of useless bullshit nobody wants or needs.”

These are not the actions of companies that truly fear missing the mark, let alone the judgment of the media, analysts or investors. These are the actions of a tech industry that has escaped any meaningful criticism — let alone regulation! — of their core businesses or new products under the auspices of “giving them a chance” or “being open to new ideas,” and those ideas are always whatever the tech industry just said, even if it’s nonsensical.

When Facebook announced it was changing its name to Meta as a means of pursuing “the successor to the mobile internet,” it didn’t really provide any proof beyond a series of extremely shitty VR apps, but not to worry, Casey Newton of Platformer was there to tell us that Facebook was going to “strive to build a maximalist, interconnected set of experiences straight out of sci-fi — a world known as the metaverse,” adding that the metaverse was “having a moment.” Similarly, Futurum Group’s Dan Newman said in April 2022 that “the metaverse was coming” and that it “would likely continue to be one of the biggest trends for years to come.”

Three years and $70 billion later, the metaverse is dead, and everybody acts as if it didn’t happen. Whoops! In a sane society, investors, analysts and the media would never trust a single word out of Mark Zuckerberg’s mouth ever again. Instead, the media gleefully covered his mid-2025 “Personal Superintelligence” blog where he promised everybody would have a “personal superintelligence” to “help you achieve your goals.” Do LLMs do that? No. Can they ever do that? No. Doesn’t matter! This is the tech industry. There is no punishment, no consequence, no critique, no cynicism, and no comeuppance — only celebration and consideration, only growth.

All the while, the largest tech firms have continued growing, always finding new ways (largely through aggressive monopolies and massive sales teams) to make Number Go Up to the point that the media, analysts and investors have stopped asking any challenging questions, and naturally assumed that they — and the financiers that back them — would never do something really stupid. The tech, business and finance media had been well-trained at this point to understand that progress was always the story, and that failure was somehow “necessary for innovation,” whether or not anything was innovative.

Over time, this created an evolutionary problem. The successes of companies like Uber — which grew to quasi-profitability after more than a decade of burning billions of dollars — convinced journalists that startups had to burn tons of money to grow. All that it took to convince some members of the media that something was a good idea was $50 million or more in funding, with larger funding rounds making it — for whatever reason — less palatable to critique a company, for fear that you would “bet against a winner,” as the assumption would be that this company would go public or get acquired, and nobody wants to be wrong, do they?

This naturally created a world of startup investment and innovation that oriented itself around the growth-at-all-costs nightmare of The Rot Economy. Startups were rewarded not for creating real businesses, or having good ideas, or even creating new categories, but for their ability to play “brainwash a venture capitalist,” either through being “a founder to bet on” or appealing to the next bazillion-dollar TAM boondoggle. Perhaps they’d find some sort of product-market fit, or grow a large audience by providing a service at an unsustainable cost, but this was all done with the knowledge of an upcoming bailout via IPO or acquisition.

Over the years, venture capital was rewarded for funding “big ideas” and that, for the most part, paid off. Eventually those “big ideas” stopped being “big ideas for necessary companies” and became “big ideas for growing as fast as possible and dumping onto the public markets or other companies afraid that they’d be left behind.”

Taking a company public used to be easy[ From 2015-2019, there were over 100 IPOs annually, with a consistent flow of M&A giving startups somewhere to sell themselves, leading up to the egregious excess of the frothy M&A and IPO market of 2021 (a year that also saw $643 billion in venture capital investment), which led to 311 IPOs that shed 60% of their value by October 2023. Years of stupid bets based on the assumption that the markets or big tech would buy any company that remotely scared them piled up.

This created the current liquidity crisis in venture capital, where funds raised after 2018 have struggled to return any investor money, making investing in venture capital firms less lucrative, which in turn made raising money from Limited Partners harder, which in turn led to less money being available for startups that were now paying higher rates as SaaS companies — some of whom were startups — gouged their customers with higher rates every year.

Every single one of these problems comes down to one simple thing: growth. Limited Partners invest in venture capitalists that can show growth, and venture capital invested in companies that would show growth, which would in turn increase their value, which would allow them to sell for a greater amount of money. The media covers companies based not on what they do but their potential value, a value that’s largely dictated by the vibes of the company and the amount of money that they’ve raised from investors.

And all of that only makes sense if there’s liquidity, and based on the overall TVPI (the amount of money you made for each dollar invested) of funds raised after 2018, the majority of VC firms have not been able to actually make their investors more than even money in years.

Why? Because they invested in bullshit. It’s that simple. The companies they invested in are dogs that will never go public or sell to another company. While many people believe that venture capital is about making early, risky bets on vestigial companies, the truth is that the majority of venture dollars go into late-stage bets. A kinder person would frame this as “doubling down on established companies,” but those of us living in reality see it for what it is — a culture that has more in common with investing in penny stocks than it does in understanding any business fundamentals.

Perhaps I’m a little bit naive, but my perception of venture capital was that it was about discovering nascent technologies and giving them the means to make their ideas a reality. The risk was that these companies were early and thus might die, but those that didn’t die would soar. Instead, Silicon Valley waits for angel and seed investors to take the risk first, reads TechCrunch, watches the (Well Well Well, If It Isn’t The) Technology Brothers, or browses Twitter all day and discovers the next thing to pile into.

The problem with a system like this is that it naturally rewards grifting, and it was inevitable that a kind of technology would come along that worked against a system that had chased out any good sense or independent thought.

Generative AI lowers the barrier of entry for anybody to cobble together a startup that can say all the right things to a venture capitalist. Vibe coding can create a “working prototype” of a product that can’t scale (but can raise money!), the nebulous problems of LLMs — their voracious need for data, the massive data security issues, and so on — offer founders the chance to create slews of nebulous “observability” and “data veracity” companies, and the burdensome cost of running anything LLM-adjacent means that venture capitalists can make huge bets on companies with inflated valuations, allowing them to raise the Net Asset Value of their holdings arbitrarily as other desperate investors pile into later rounds.

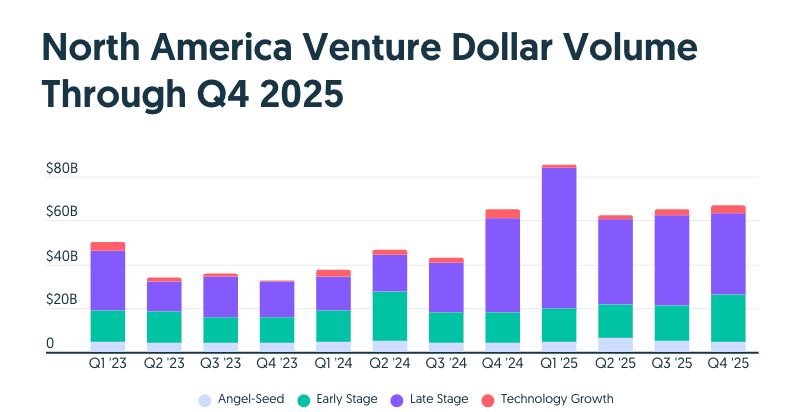

As a result, AI startups took up 65% of all venture capital funding in Q4 2025. Venture capital’s fundamental disconnection from value-creation (or reality) has led to hundreds of billions of dollars flowing into AI startups that have already-negative margins that get worse as their customer base grows and the cost of inference (creating outputs) is increasing, and at this point it’s obvious that it is impossible to create a foundation lab or LLM-powered service that makes a profit, on top of the fact that it appears that renting the GPUs for AI services is also unprofitable.

I also need to be clear that this is far, far worse than the dot com bubble.

US venture capital invested $11.49 billion ($23.08bn in today’s money) in 1997, $14.27 billion ($28.21 billion in today’s money) in 1998, $48.3 billion ($95.50 billion in today’s money) in 1999, and over $100 billion ($197.71 billion) in 2000 for a grand total of $344.49 billion (in today’s money) — a mere $6.174 billion more than the $338.3 billion raised in 2025 alone, with somewhere between 40% and 50% of that (around $168 billion) going into AI investments, and in 2024, North American AI startups raised around $106 billion.

According to the New York Times, “48 percent of dot-com companies founded since 1996 were still around in late 2004, more than four years after the Nasdaq’s peak in March 2000.” The ones that folded were predominantly dodgy and nakedly unsustainable eCommerce shops like WebVan ($393m in venture capital), Pets.com ($15m) and Kozmo ($233m), all of which filed to go public, though Kozmo failed to dump itself onto the markets in time.

Yet in a very real sense, the “dot com bubble” that everybody experienced had very little to do with actual technology. Investors in the public markets rushed with their eyes closed and their wallets out to invest in any company that even smelled like the computer, leading to basically any major tech or telecommunications stock trading at a ridiculous multiple of their earnings per share (60x in Microsoft’s case).

The bubble burst when the bullshit dot-com stocks died on their ass and the world realized that the magic of the internet was not a panacea that would fix every business model, and there was no magic moment where a company like WebVan or Pets.com would turn a horribly-unprofitable business into a real one. Similarly, companies like Lucent Technologies stopped being rewarded for doing dodgy, circular deals with companies like Winstar, leading to the collapse of the telecommunications bubble that led to millions of miles of dark fiber being sold dirt cheap in 2002. The oversupply of dark fiber was eventually seen as a positive, leading to an eventual surge in demand as billions of people came online toward the end of the 2000s.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Ed, isn’t that exactly what’s happening here? We’ve got overvalued startups, we’ve got multiple unprofitable, unsustainable AI companies promising to IPO, we’ve got overvalued tech stocks, and we’ve got one of the largest infrastructural buildouts of all time. Tech companies are trading at ridiculous multiples of their earnings-per-share, but the multiples aren’t as high. That’s good, right?

No. No it isn’t. AI boosters and well-wishers are obsessed with making this comparison because saying “things worked out after the dot com bubble” allows them to rationalize doing stupid, destructive and reckless things.

Even if this was just like the dot com bubble, things would be absolutely fucking catastrophic — the NASDAQ dropped 78% from its peak in March 2000 — but due to the incredible ignorance of both the private and public power brokers of the tech industry, I expect consequences that range from calamitous to catastrophic, dependent almost entirely on how long the bubble takes to burst, and how willing the SEC is to greenlight an IPO.

The AI bubble bursting will be worse, because the investments are larger, the contagion is wider, and the underlying asset — GPUs — are entirely different in their costs, utility and basic value than dark fiber. Furthermore, the basic unit economics of AI — both in its infrastructure and the AI companies themselves — are magnitudes more horrifying than anything we saw in the dot com bubble.

In simpler terms, I’m really fucking worried, and I’m sick and tired of hearing people making this comparison.

2026-01-01 02:00:53

Hey all,

I'm not dropping this on the actual newsletter feed because it's a little self-indulgent and I'm not sure 88,000 or so people want an email about it.

If you want to support my work directly, please subscribe to my premium newsletter. It’s $70 a year, or $7 a month, and in return you get a weekly newsletter that’s usually anywhere from 5000 to 15,000 words. In the bottom right hand corner of your screen you’ll see a red circle — click that and select either monthly or annual.

If you have any issues signing up for premium, please email me at [email protected].

If you want to give a gift subscription, use this link: https://www.wheresyoured.at/gift-subscription/

I have a lot of trouble giving myself credit for anything, and genuinely think I could be doing more or that I "didn't do that much" because I'm at a computer or on a microphone versus serving customers in person or something or rather.

To try and give some sort of scale to the work from the last year, I've written down the highlights. It appears that 2025 was an insane year for me.

Here's the rundown:

I also did no less than 50 different interviews, with highlights including:

Next year I will be finishing up my book Why Everything Stopped Working (due out in 2027), and continuing to dig into the nightmare of corporate finance I've found myself in the center of.

I have no idea what happens next. My fear - and expectation - is that many people still do not realize that there is an AI bubble or will not accept how significant and dangerous the bubble is, meaning that everybody is going to act like AI is the biggest most hugest and most special thing in the world right up until they accept that it isn't.

I will always cover tech, but I get the sense I'll be looking into other things next year - private equity, for one - that have caught my eye toward the end of the year.

I realize right now everything feels a little intense and bleak, but at this time of year it's always worth remembering to be kinder and more thoughtful toward those close to us. It's cheesy, but it's the best thing you can possibly do. It's easy to feel isolated by the amount of hogs oinking at the prospect of laying you off or replacing you - and it turns out there are far more people that are afraid or outraged than there are executives or AI boosters.

Never forget (or forgive them for) what they've done to the computer, and never forget that those scorned by the AI bubble are legion. Join me on r/Betteroffline, you are far from alone.

I intend to spend the next year becoming a better writer, analyst, broadcaster, entertainer and person. I appreciate every single one of you that reads my work, and hope you'll continue to do so in the future.

See you in 2026,

Ed Zitron