2026-02-18 00:15:11

This is the quarterly links ‘n’ updates post, a selection of things I’ve been reading and doing for the past few months.

First up, a series of unfortunate events in science:

When Prophecy Fails is supposed to be a classic case study of cognitive dissonance: a UFO cult predicts an apocalypse, and when the world doesn’t end, they double down and start proselytizing even harder: “I swear the UFO is coming any minute!”

A new paper finds a different story in the archives of the lead author, Leon Festinger. Up to half of the attendees at cult meetings may have been undercover researchers. One of them became a leader in the cult and encouraged other members to make statements that would look good in the book. After the failed prediction, rather than doubling down, some of the cultists walked back their statements or left altogether.

Between this, the impossible numbers in the original laboratory study of cognitive dissonance, and a recent failure to replicate a basic dissonance effect, things aren’t looking great for the phenomenon.1 But that only makes me believe in it harder!

Another classic sadly struck from the canon of behavioral/brain sciences: the neurologist Oliver Sacks appears to have greatly embellished or even invented his case studies. In a letter to his brother, Sacks described his blockbuster The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat as a book of “fairy tales [...] half-report, half-imagined, half-science, half-fable”.

This is exactly how the Stanford Prison Experiment and the Rosenhan experiment got debunked—someone started rooting around in the archives and found a bunch of damning notes. I’m confused: back in the day, why was everybody meticulously documenting their research malfeasance?

If you ever took PSY 101, you’ve probably heard of this study from 1974. You show people a video of a car crash, and then you ask them to estimate how fast the cars were going, and their answer depends on what verb you use. For example, if you ask “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” people give higher speed estimates than if you ask, “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” (Emphasis mine). This study has been cited nearly 4,000 times, and its first author became a much sought-after expert witness who testifies about the faultiness of memory.

A blogger named Croissanthology re-ran the study with nearly 10x as many participants (446 vs. 45 in the original). The effect did not replicate. No replication is perfect, but no original study is either. And remember, this kind of effect is supposed to be so robust and generalizable that we can deploy it in court.

I think the underlying point of this research is still correct: memory is reconstructed, not simply recalled, so what we remember is not exactly what we saw. But our memories are not so fragile that a single word can overwrite them. Otherwise, if you ever got pulled over for speeding, you could just be like, “Officer, how fast was I going when my car crawled past you?”

In one study from 1995, physicians who were shown multiple treatment options were more likely to recommend no treatment at all. The researchers thought this was a “choice overload” effect, like “ahhh there’s too many choices, so I’ll just choose nothing at all”. In contrast, a new study from 2025 found that when physicians were shown multiple treatment options, they were somewhat more likely to recommend a treatment.

I think “choice overload” is like many effects we discover in psychology: can it happen? Yes. Can the opposite also happen? Also yes. When does it go one way, and when does it go the other? Ahhh you’re showing me too many options I don’t know.

Okay, enough dumping on other people’s research. It’s my turn in the hot seat.

In 2022, my colleague Jason Dana and I published a paper showing that people don’t know how public opinion has changed. Like this:

A new paper by Irina Vartanova, Kimmo Eriksson, and Pontus Strimling reanalyzes our data and finds that actually, people are great at knowing how public opinion has changed.

What gives? We come to different conclusions because we ask different questions. Jason and I ask, “When people estimate change, how far off are they from the right answer?” Vartanova et al. ask, “Are people’s estimates correlated with the right answer?” These approaches seem like they should give you the same results, but they don’t, and I’ll show you why.

Imagine you ask people to estimate the size of a house, a dog, and a stapler. Vartanova’s correlation approach would say: “People know that a house is bigger than a dog, and that a dog is bigger than a stapler. Therefore, people are good at estimating the sizes of things.” Our approach would say: “People think a house is three miles long, a dog is two inches, and a stapler is 1.5 centimeters. Therefore, people are not good at estimating the sizes of things.”

I think our approach is the right one, for two reasons. First, ours is more useful. As the name implies, a correlation can only tell you about the relationships between things. So it can’t tell you whether people are good at estimating the size of a house. It can only tell you whether people think houses are bigger than dogs.

Second, I think our approach is much closer to the way people actually make these judgments in their lives. If I asked you to estimate the size of a house, you wouldn’t spontaneously be like, “Well, it’s bigger than a dog.” You’d just eyeball it. I think people do the same thing with public opinion—they eyeball it based on headlines they see, conversations they have, and vibes they remember. If I asked you, “How have attitudes toward gun control changed?” you wouldn’t be like, “Well, they’ve changed more than attitudes toward gender equality.”2

While these reanalyses don’t shift my opinion, I’m glad people are looking into shifts in opinions at all, and that they found our data interesting enough to dig into.

THE LOOP is a online magazine produced by my friends Slime Mold Time Mold. The newest issue includes:

a study showing that people maybe like orange juice more when you add potassium to it

a pseudonymous piece by me

scientific skepticism of the effectiveness of the Squatty Potty, featuring this photo:

This issue of THE LOOP was assembled at Inkhaven, a blogging residency that is currently open for applications. I visited the first round of this program and was very impressed.

Also at Inkhaven, I interviewed the pseudonymous blogger Gwern about his writing process. Gwern is kind of hard to explain. He’s famous on some parts of the internet for predicting the “scaling hypothesis”—the fact that progress in AI would come from dumping way more data into the models. But he also writes poetry, does self-experiments, and sustains himself on $12,000 a year. He reads 10 hours a day every day, and then occasionally writes for 30 minutes. Here’s what he said when I was like, “Very few people do experiments and post them on the internet. Why do you do it?”

I did it just because it seemed obviously correct and because… Yeah. I mean, it does seem obviously correct.

For more on what I learned by interviewing a bunch of bloggers, see I Know Your Secret.

I really like this article by the artist known as fnnch: How to Make a Living as an Artist. It’s super practical and clear-headed writing on a subject that is usually more stressed about than thought about. Here’s a challenge: which of these seven images became successful, allowing fnnch to do art full time?

I’ll give the answer at the bottom of the post.

Anyone who grew up in the pre-internet days probably heard the myth that “you swallow eight spiders every year in your sleep”, and back then, we just had to believe whatever we heard.

Post-internet, anyone can quickly discover that this “fact” was actually a deliberate lie spread by a journalist named Lisa Birgit Holst. Holst included the “eight spiders” myth in a 1993 article in a magazine called PC Insider, using it as an example of exactly the kind of hogwash that spreads easily online.

That is, anyway, what most sources will tell you. But if you dig a little deeper, you’ll discover that the whole story about Lisa Birgit Holst is also made up. “Lisa Birgit Holst” is an anagram of “This is a big troll”; the founder of Snopes claims he came up with it in his younger and wilder days. The true origin of the spiders myth remains unknown.

In 2015, Reagan National Airport in DC received 8,760 noise complaints; 6,852 of those complaints (78%) came from a single household, meaning the people living there called to complain an average of 19 times a day. This seems to be common both across airports and across complaint systems in general: the majority of gripes usually comes from a few prolific gripers. Some of these systems are legally mandated to investigate every complaint, so this means a handful of psychotic people with telephones—or now, LLMs—can waste millions of dollars. I keep calling to complain about this, but nobody ever does anything about it.

:

Did you know that this is the most compact known way to pack 11 squares together into a larger square?

Really makes you think about the mindset of whoever made the universe, am I right?

(More here.)

digs up the “world’s saddest cookbook” and finds that it’s…pretty good?

He successfully makes steak and eggs, two things that are supposed to be impossible in the microwave. The only thing you can’t make? Multiple potatoes.

There’s a reason the book is called Microwave Cooking for One and not Microwave Cooking for a Large, Loving Family. […] It’s because microwave cooking becomes exponentially more complicated as you increase the number of guests. […] Baking potatoes in the microwave is an NP-hard problem.

I was tickled to see that an actual Christian theologian/data scientist found my post called There Are No Statistics in the Kingdom of God. He mostly agreed with the argument, but he does think statistics will continue to exist in heaven. We shall see!

I was back on ’s “Plain English” podcast talking about the decline of deviance.

I was also on the “What Is a Good Life?” podcast with talking about the good life.

“Why Aren’t Smart People Happier” won a Sidney Award, recognizing “excellence in nonfiction essays”:

And finally, the answer to the question I posed earlier: the art that made fnnch famous was the honey bear. Go figure!

I know people will be like “there are hundreds of studies that confirm cognitive dissonance”. But if you look at that study that didn’t replicate, it had 10 participants per condition. That’s way too few to detect anything interesting—you need 46 men and 46 women just to demonstrate the fact that men weigh more than women, on average. Many of those other cognitive dissonance studies have similarly tiny samples, so their existence doesn’t put me at ease. Plus, the theorizing here is so squishy that many different patterns of results could arguably confirm or disconfirm the theory: here’s someone arguing that, in fact, the failure to replicate was actually a success.

A reporter tracked down Elliot Aronson, a student of Festinger and a dissonance researcher himself, and posed the following question to him:

I asked him how the theory could be falsified, since any choice a person made could be attributed to dissonance. “It’s hard to disprove anything,” he said.

Very true, on many levels.

There’s one more point where we disagree. Vartanova et al. point out that 70% of estimates are in the right direction—as in, if support for gun control went down, 70% of participants correctly guessed that it went down. The researchers look at that number and go, “That seems pretty good”. We look at the exact same number and go, “That seems pretty bad”. Obviously this is a judgment call, but getting the direction right is such a low bar that we think it’s remarkable so many people don’t clear it. Getting the direction of change wrong is a bit like saying that a dog is bigger than a house.

2026-02-04 00:28:19

Underrated Ways to Change the World is one of my most-read posts of all time, I think because people see the state of the world and they’re like, “Oh no, someone should do something about this!” and then they’re like “But what should I do about this?” Every problem seems so impossibly large and complicated, where do you even start?

You start by realizing that nobody can clean up this mess single-handedly, which is fine, because we’ve got roughly 16 billion other hands at the ready. All any of us have to do is find some neglected corner and start scrubbing.

That’s why I take note whenever I spot someone who seems uncommonly clever at making things better, or whenever I trip over a problem that doesn’t seem to have anyone fixing it. I present them to you here in the hopes that they’ll inspire you as they’ve inspired me.

According to this terrific profile, Donald Shoup “has a strong claim on being the scholar who will have had the greatest impact on your day-to-day life”. Shoup did not study cancer, nuclear physics, or AI. No, Shoup studied parking. He spent his whole career documenting the fact that “free” parking ultimately backfires, and it’s better to charge for parking instead and use the revenues to make neighborhoods nicer: plant trees, spruce up the parks, keep the sidewalks clean.1

Shoup’s ideas have been adopted all over the world, with heartening results. When you price parking appropriately, traffic goes down, fewer people get tickets, and you know there’s going to be a space waiting for you when you arrive.

Many so-called “thought leaders” strive for such an impact and never come close. What made Shoup so effective? Three things, says his student M. Nolan Gray:

He picked an unsexy topic where low-hanging fruit was just waiting to be picked.

He made his ideas palatable to all sorts of politics, explaining to conservatives, libertarians, progressives, and socialists how pay-for-parking regimes fit into each of their ideologies.2

He maintained strict message discipline. When asked about the Israel-Palestine protests on campus, he reportedly responded, “I’m just wondering where they all parked”.

So the next time you find a convenient parking spot, thank Shoup, and the next time you want to apply your wits to improving the world, be Shoup.

Jane Jacobs, the great urban theorist, once wrote that the health of a neighborhood depends on its “public characters”.3 For instance, two public characters in Jacobs’ neighborhood are Mr. and Mrs. Jaffe, who own a convenience store. On one winter morning, Jacobs observes the Jaffes provide the following services to the neighborhood, all free of charge:

supervised the small children crossing at the corner on the way to [school]

lent an umbrella to one customer and a dollar to another

took custody of a watch to give the repair man across the street when he opened later

gave out information on the range of rents in the neighborhood to an apartment seeker

listened to a tale of domestic difficulty and offered reassurance

told some rowdies they could not come in unless they behaved and then defined (and got) good behavior

provided an incidental forum for half a dozen conversations among customers who dropped in for oddments

set aside certain newly arrived papers and magazines for regular customers who would depend on getting them

advised a mother who came for a birthday present not to get the ship-model kit because another child going to the same birthday party was giving that

Some people think they can’t contribute to the world because they have no unique skills. How can you help if you don’t know kung fu or brain surgery? But as Jacobs writes, “A public character need have no special talents or wisdom to fulfill his function—although he often does. He just needs to be present [...] his main qualification is that he is public, that he talks to lots of different people.” Sometimes all we need is a warm body that is willing to be extra warm.

I once did a high school science fair experiment where I put Mentos in different carbonated beverages and measured the height of the resulting geysers. The scientific value of this project was, let’s say, limited, but I did learn something interesting: despite how it looks to the naked eye, bubbles don’t come from nowhere. They only form at nucleation sites—little pits and scratches where molecules can gather until they reach critical mass.

The same thing is true of human relationships. People are constantly crashing against each other in the great sea of humanity, but only under special conditions do they form the molecular bonds of friendship. As far as I can tell, these social nucleation sites only appear in the presence of what I would call unreasonable attentiveness.

For instance, my freshman year hallmates were uncommonly close because our resident advisor was uncommonly intense. Most other groups shuffle halfheartedly through the orientation day scavenger hunt; Kevin instructed us to show up in gym shorts and running shoes, and barked at us back and forth across campus as we attempted to locate the engineering library and the art museum. When we narrowly missed first place, he hounded the deans until they let us share in the coveted grand prize, a trip to Six Flags.

We bonded after that, not just because we had all gotten our brains rattled at the same frequency on the Superman rollercoaster, but because we could all share a knowing look with each other like, “This guy, right?” Kevin’s unreasonable attentiveness made our hallway A Thing. He created a furrow in the fabric of social space-time where a gaggle of 18-year-olds could glom together.

Being in the presence of unreasonable attentiveness isn’t always pleasant, but then, nucleation sites are technically imperfections. Bubbles don’t form in a perfectly smooth glass, and human groups don’t form in perfectly smooth experiences. Unreasonable attentiveness creates the slight unevenness that helps people realize they need something to hold onto—namely, each other.

Peter Askew didn’t intend to become an onion merchant. He just happened to be a compulsive buyer of domain names, and when he noticed that VidaliaOnions.com was up for sale, he snagged it. He then discovered that some people love Vidalia onions. Like, really love them:

During a phone order one season – 2018 I believe – a customer shared this story where he smuggled some Vidalias onto his vacation cruise ship, and during each meal, would instruct the server to ‘take this onion to the back, chop it up, and add it onto my salad.’

But these allium aficionados didn’t have a good way to get in-season onions because Vidalias can only be grown in Georgia, and it’s a pain for small farms to maintain a direct-to-consumer shipping business on the side. Enter Askew, who now makes a living by pleasing the Vidalia-heads:

Last season, while I called a gentleman back regarding a phone order, his wife answered. While I introduced myself, she interrupted me mid-sentence and hollered in exaltation to her husband: “THE VIDALIA MAN! THE VIDALIA MAN! PICK UP THE PHONE!”

People have polarized views of business these days. Some people think we should feed grandma to the economy so it can grow bigger, while other people think we should gun down CEOs in the street. VidaliaOnions.com is, I think, a nice middle ground: you find a thing people want, you give it to them, you pocket some profit. So if you want an honest day’s work, maybe figure out what else people want chopped up and put on their cruise ship salads.

I know a handful of people who have needed immigration lawyers, and they all say the same thing: there are no good immigration lawyers.

I think this is because the most prosocially-minded lawyers become public defenders or work at nonprofits representing cash-strapped clients, while the most capable and amoral lawyers go to white-shoe firms where they can make beaucoup bucks representing celebrity murderers and Halliburton. This leaves a doughnut hole for people who aren’t indigent, but also aren’t Intel. So if you want to help people, but you also don’t want to make peanuts, you could do a lot of good by being an honest and competent immigration lawyer.

I think there are lots of jobs like that, roles that don’t get good people because they aren’t sacrificial enough to attract the do-gooders and they aren’t lucrative enough to attract the overachievers. Home repair, movers, daycares, nursing homes, local news, city government—these are places where honesty and talent can matter a lot, but supply is low.

So if your career offers you the choice of being a starving saint or a wealthy sinner, consider being a middle-class mensch instead. You may not be helping the absolute neediest people, and you may not be able to afford a yacht, but there are lots of folks out there who would really like some help getting their visas renewed, and they’d be very happy to meet you.

I have this game I like to play called Viral Statistics Bingo, where you find statistics that have gone viral on the internet and you try to trace them back to their original source. You’ll usually find that they have one of five dubious origins:

A crummy study done in like 1904

A study that was done on mice

A book that’s out of print and now no one can find it

A complete misinterpretation of the data

It’s just something some guy said once

That means anyone with sufficient motivation can render a public service by improving the precision of a famous number. For example, the sex worker/data scientist realized that no one has any idea what percentage of sex workers are victims of human trafficking. By combining her own surveys with re-analysis of publicly available data, she estimates that it’s 3.2%. That number is probably not exactly right, but then, no statistic is exactly right—the point is that it puts us in the right ballpark, that you can check her work for yourself, and that it’s a lot better than basing our numbers on a study done in mice.

The US does a bad job regulating clinical trials, and it means we don’t invent as many life-saving medicines as we could. is trying to change that, and she says that scientists and doctors often give her damning information that would be very helpful for her reform efforts. But her sources refuse to go on the record because it might put their careers in a bit of jeopardy. Not real jeopardy, mind you, like if you drive your minivan into the dean’s office or if you pants the director of the NIH. We’re talking mild jeopardy, like you might be 5% less likely to win your next grant.

She refers to this as “hobbitian courage”, as in, not the kind of courage required to meet an army of Orcs on the battlefield, but the courage required to take a piece of jewelry on a field trip to a volcano:

The quieter, hobbitian form of courage that clinical development reform (or any other hard systems problem) requires is humble: a researcher agreeing to let you cite them, an administrator willing to deviate from an inherited checklist, a policymaker ready to question a default.

It’s understandable that most people don’t want to risk their lives or blow up their careers to save the world. But most situations don’t actually call for the ultimate sacrifice. So if you’re not willing to fall on your sword, consider: would you fall on a thumbtack instead?

Every human lives part-time in a Kafka novel. In between working, eating, and sleeping, you must also navigate the terrors of various bureaucracies that can do whatever they want to you with basically no consequences.

For example, if you have the audacity to go to a hospital in the US, you will receive mysterious bills for months afterwards (“You owe us $450 because you went #2 in an out-of-network commode”). If you work at a university, you have to wait weeks for an Institutional Review Board to tell you whether it’s okay to ask people how much they like Pop-Tarts. The IRS knows how much you owe in taxes, but instead of telling you, you’re supposed to guess, and if you guess wrong, you owe them additional money—it’s like playing the world’s worst game show, and the host also has a monopoly on the legitimate means of violence.

If you can de-gum the gears of one of these systems—even a sub-sub-sub-system!—you could improve the lives of millions of people. To pick a totally random example, if you work for the Department of Finance for the City of Chicago, and somebody is like “Hey, this very nice blogger just moved to town and he didn’t know that you have to get a sticker from us in order to have a vehicle inside city limits, let’s charge him a $200 fine!”, you could say in reply, “What if we didn’t do that? What if we asked him to get the sticker instead, and only fined him if he didn’t follow through? Because seriously, how are people supposed to know about this sticker system? When you move to Chicago, does the ghostly form of JB Pritzker appear to you in a dream and explain that you need both a sticker from the state of Illinois, which goes on the license plate, and a sticker from the city of Chicago, which goes on your windshield? Do we serve the people, or do we terrorize them?” Just as one example.

I used to perform at a weekly standup gig when I lived in the UK, and this guy Wally would always be there in the second row. I got the impression that he didn’t have anywhere else to be, but we didn’t mind, because Wally was Good Audience.

When the jokes were good, he laughed loud and hard, and when the jokes were bad, he politely waited for more good jokes. Wally brought his friends, they brought their friends, and having more Good Audience made the acts better, too. (When comedians only perform for each other, no one laughs.) Eventually the gig got big, so big that it would sell out every week, and we’d have to set aside a ticket for Wally or else he wouldn’t get in. Ten years later, that show is still running.

Fran Leibowitz once said that the AIDS epidemic wiped out not just a generation of artists, but also a generation of audience. Great writers, performers, filmmakers, etc. cannot exist without great readers, watchers, and commentators—and not just because they open their wallets and put butts in seats, but because they pluck the diamonds out of the rough, they show it to their friends and pass it on to their kids, they raise it above their heads while wading through the sea of slop, shouting, “This! Look at this!”

Years ago, my friend Drew was visiting me when we noticed a whiff of natural gas in the hallway outside my apartment. I thought it was nothing—my building wasn’t the nicest, and it often smelled of many things—but Drew, who is twice as affable and Midwestern as I am, insisted we call the gas company. A bored technician arrived and halfheartedly waved his gas-detecting wand around my neighbor’s door, at which point his eyes got wide. He rushed to the basement, where he saw the gas meter spinning wildly, meaning that gas was pouring into my neighbor’s apartment.

“We gotta get this door open,” he said.

No one answered when we pounded on the door, so we summoned the fire department, who busted open a window and found my neighbor unconscious on the floor. His stove’s burners was on, but not lit, turning his apartment into a gas chamber. They told us the guy probably would have died if someone didn’t call, and the building might have caught on fire.

I was glad the guy survived, but I was ashamed that he had to be saved by a total stranger, while his own neighbor was ready to walk on by. I should have known him! I should have brought him Christmas cookies! We should have played checkers in the park on Saturdays! In the days afterward, I fantasized about knocking on his door or leaving him a note, like, “Hey! I notice you are elderly and alone, and I am young and nearby, maybe we should get a Tuesdays with Morrie thing going?”

But I never did that. I was too intimidated. Besides, am I supposed to become bosom buddies with every schmuck who lives in my building? Who’s got time for that?

Now that I’ve lived among many schmucks in many different buildings, I realized that I didn’t need to be this guy’s best friend. I just needed to be his acquaintance. If I knew his name, if I had even spoken to him once in the hallway, then when I got a noseful of gas outside his door, I would have thought to myself, “Oh, Rob’s apartment shouldn’t smell like that.” Rob ‘n’ me were never going to be Mitch and Morrie, but we could have easily been Guys Who Kind of Recognize Each Other and Would Be Willing to Report the Presence of Dangerous Chemicals on Each Other’s Behalf.

A lot of well-intentioned people suffer from what we might call Superhero Syndrome: they want to save the world, but they want it to be saved by them in particular. They want to be the one who blows up the Death Star, not the one who washes the X-Wings.

This is a seductive fantasy because it disguises selfishness as sacrifice. It promises to excuse a lifetime of mediocrity with one great gesture, to pay off all your karmic debts in one fell swoop. The result is a world full of heroes-in-waiting who comfort themselves by thinking they would jump on a grenade if the situation ever presented itself, which fortunately it never does.

We do occasionally need someone to shoot torpedos into the exhaust port of a giant doomsday machine. But most of the time, we need people who sell onions, people who make sure the kids get to school safely, people who will show up to the comedy gig and laugh. I’d like to live in a world full of people like that, I’d be happy to pay for the sticker that lets me park there.

Free parking sounds nice, so why isn’t it a good idea? A few reasons: it increases housing prices through mandatory off-street parking requirements, prevents walkable neighborhoods from being built, transfers money from poorer people to richer people (everyone pays to maintain the curb, but only car owners benefit from it), wastes time (the average driver may spend something like 50 hours a year just looking for a spot), and causes congestion—in dense areas, up to 1/3 of drivers are trying to find parking at any given time.

This is, by the way, a terrific example of what I call memetic flexibility.

This comes from The Death and Life of Great American Cities, p. 60-61, 68

2026-01-28 00:22:32

A few months ago, I got to interview a bunch of bloggers at a writing retreat. I discovered that they all had one thing in common: each one was in possession of a secret.

I don’t mean that they, like, murdered their boyfriend and got away with it, or that they’re sexually attracted to mollusks. I mean that they had all tapped some ve…

2026-01-21 02:55:47

The hot new theory online is that reading is kaput, and therefore civilization is too. The rise of hyper-addictive digital technologies has shattered our attention spans and extinguished our taste for text. Books are disappearing from our culture, and so are our capacities for complex and rational thought. We are careening toward a post-literate society, where myth, intuition, and emotion replace logic, evidence, and science. Nobody needs to bomb us back to the Stone Age; we have decided to walk there ourselves.

I am skeptical of this thesis. I used to study claims like these for a living, so I know that the mind is primed to believe narratives of decline. We have a much lower standard of evidence for “bad thing go up” than we do for “bad thing go down”.

Unsurprisingly, then, stories about the end of reading tend to leave out some inconvenient data points. For example, book sales were higher in 2025 than they were in 2019, and only a bit below their high point in the pandemic. Independent bookstores are booming, not busting; 422 new indie shops opened last year alone. Even Barnes and Noble is cool again.

The actual data on reading isn’t as apocalyptic as the headlines imply. Gallup surveys suggest that some mega-readers (11+ books per year) have become moderate readers (1-5 books per year), but they don’t find any other major trends over the past three decades:

Other surveys document similarly moderate declines. For instance, data from the National Endowment for the Arts finds a slight decrease in reading over the past decade:

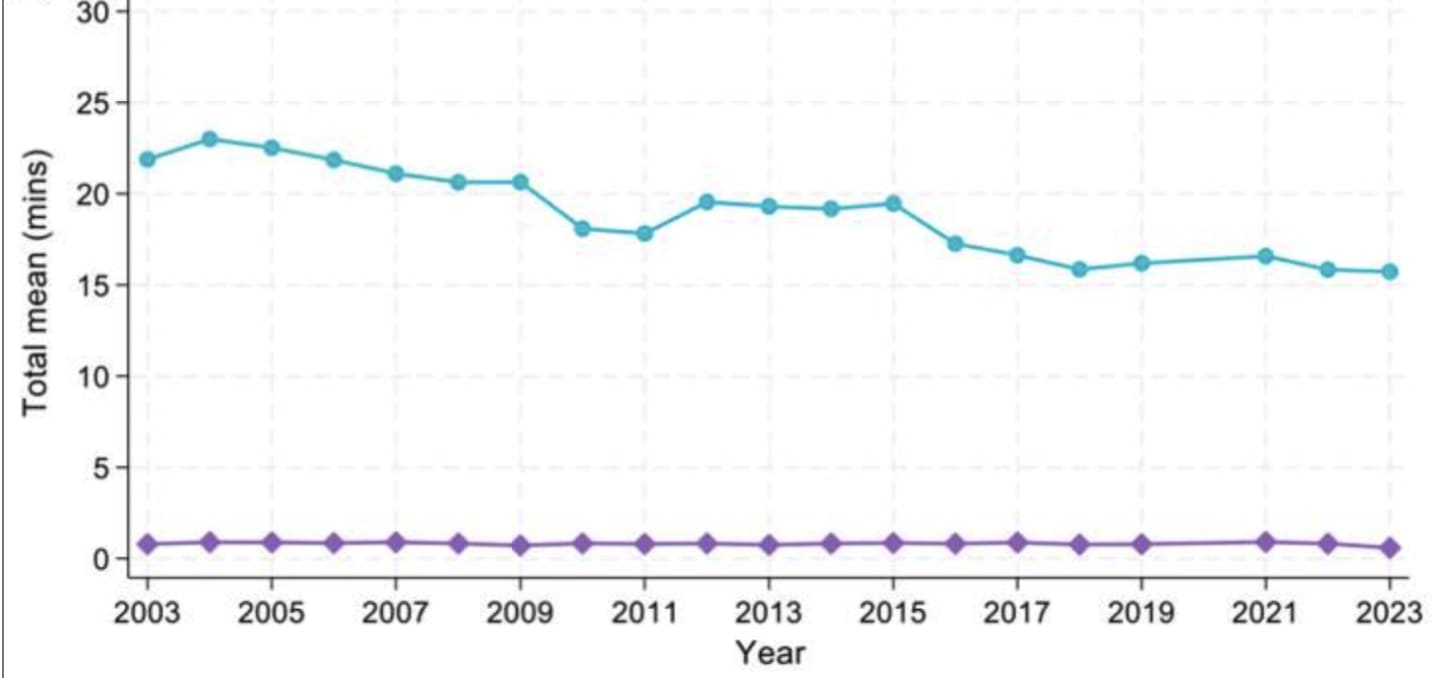

And the American Time Use Survey shows a dip in reading time from 2003 to 2023:

These are declines, no doubt. But if you look closely at the reading time data, you’ll notice that the dip between 2003 and 2011 is about twice the size of the dip between 2011 and 2023. In fact, the only meaningful changes happen in 2009 and 2015. I’d say we have two effects here: a larger internet effect and a smaller smartphone effect, neither of which is huge. If the data is right, the best anti-reading intervention is not a 5G-enabled iPhone circa 2023, but a broadband-enabled iMac circa 2009.

Ultimately, the plausibility of the “death of reading” thesis depends on two judgment calls.

First, do these effects strike you as big or small? Apparently, lots of people see these numbers and perceive an emergency. But we should submit every aspiring crisis to this hypothetical: how would we describe the size of the effect if we were measuring a heartening trend instead instead of a concerning one?

Imagine that time-use graph measured cigarette-smoking instead of book-reading. Would you say that smoking “collapsed” between 2003 and 2023? If we had been spending a billion dollars a year on a big anti-smoking campaign that whole time, would we say it worked? Kind of, I’d say, but most of the time the line doesn’t budge. I wouldn’t be unfurling any “Mission Accomplished” banners, which is why I am not currently unfurling any “Mission Failed” banners either.1

The second judgment call: do you expect these trends to continue, plateau, or even reverse? The obvious expectation is that technology will get more distracting every year. And the decline in reading seems to be greater among college students, so we should expect the numbers to continue ticking downward as older bookworms are replaced by younger phoneworms. Those are both reasonable predictions, but two facts make me a little more doubtful.

Fact #1: there are signs that the digital invasion of our attention is beginning to stall. We seem to have passed peak social media—time spent on the apps has started to slide. App developers are finding it harder and harder to squeeze more attention out of our eyeballs, and it turns out that having your eyeballs squeezed hurts, so people aren’t sticking around for it. The “draw people in” phase of the internet was unsurprisingly a lot more enticing than the “shake ‘em down” phase—what we now refer to, appropriately, as “enshittification”. The early internet felt like sipping an IPA with friends; the late internet feels like taking furtive shots of Southern Comfort to keep the shakes at bay. So it’s no wonder that, after paying $1000 for a new phone, people will then pay an additional $50 for a device that makes their phone less functional.

Fact #2: reading has already survived several major incursions, which suggests it’s more appealing than we thought. Radio, TV, dial-up, Wi-Fi, TikTok—none of it has been enough to snuff out the human desire to point our pupils at words on paper. Apparently books are what hyper-online people call “Lindy”: they’ve lasted a long time, so we should expect them to last even longer.

It is remarkable, even miraculous, that people who possess the most addictive devices ever invented will occasionally choose to turn those devices off and pick up a book instead. If I was a mad scientist hellbent on stopping people from reading, I’d probably invent something like the iPhone. And after I released my dastardly creation into the world, I’d end up like the Grinch on Christmas morning, dumfounded that my plan didn’t work: I gave them all the YouTube Shorts they could ever desire and they’re still...reading!!

Perhaps there are frontiers of digital addiction we have yet to reach. Maybe one day we’ll all have Neuralinks that beam Instagram Reels directly into our primary visual cortex, and then reading will really be toast.

Maybe. But it has proven very difficult to artificially satisfy even the most basic human pleasures. Who wants a birthday cake made with aspartame? Who would rather have a tanning bed than a sunny day? Who prefers to watch bots play chess? You can view high-res images of the Mona Lisa anytime you want, and yet people will still pay to fly to Paris and shove through crowds just to get a glimpse of the real thing.

I think there is a deep truth here: human desires are complex and multidimensional, and this makes them both hard to quench and hard to hack. That tinge of discontent that haunts even the happiest people, that bottomless hunger for more even among plenty—those are evolutionary defense mechanisms. If we were easier to please, we wouldn’t have made it this far. We would have gorged ourselves to death as soon as we figured out how to cultivate sugarcane.

That’s why I doubt the core assumption of the “death of reading” hypothesis. The theory heavily implies that people who would once have been avid readers are now glassy-eyed doomscrollers because that is, in fact, what they always wanted to be. They never appreciated the life of the mind. They were just filling time with great works of literature until TikTok came along. The unspoken assumption is that most humans, other than a few rare intellectuals, have a hierarchy of needs that looks like this:

I don’t buy this. Everyone, even people without liberal arts degrees, knows the difference between the cheap pleasures and the deep pleasures. No one pats themselves on the back for spending an hour watching mukbang videos, no one touts their screentime like they’re setting a high score, and no one feels proud that their hand instinctively starts groping for their phone whenever there’s a lull in conversation.2

Finishing a great nonfiction book feels like heaving a barbell off your chest. Finishing a great novel feels like leaving an entire nation behind. There are no replacements for these feelings. Videos can titillate, podcasts can inform, but there’s only one way to get that feeling of your brain folds stretching and your soul expanding, and it is to drag your eyes across text.

That’s actually where I agree with the worrywarts of the written word: all serious intellectual work happens on the page, and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise. If you want to contribute to the world of ideas, if you want to entertain and manipulate complex thoughts, you have to read and write.

According to one theory, that’s why writing originated: to pin facts in place. At first, those facts were things like “Hirin owes Mushin four bushels of wheat”, but once you realize that knowledge can be hardened and preserved by encoding it in little squiggles, you unlock a whole new realm of logic and reasoning.

That’s why there’s no replacement for text, and there never will be. Thoughts that can survive being written into words are on average truer than thoughts that never leave the mind. You know how you can find a leak in a tire by squirting dish soap on it and then looking for where the bubbles form? Writing is like squirting dish soap on an idea: it makes the holes obvious.

That doesn’t mean every piece of prose is wonderful, just that it can be. And when it reaches those heights, it commands a power that nothing else can possess.

I didn’t always believe this. I was persuaded on this point recently when I met an audio editor named Julia Barton, who was writing a book about the history of radio. I thought that was funny—shouldn’t the history of radio be told as a podcast?

No, she said, because in the long run, books are all that matter. Podcasts, films, and TikToks are good at attracting ears and eyes, but in the realm of ideas, they punch below their weight. Thoughts only stick around when you print them out and bind them in cardboard.

I think Barton’s thesis is right. At the center of every long-lived movement, you will always find a book. Every major religion has its holy text, of course, but there is also no communism without the Communist Manifesto, no environmentalism without Silent Spring, no American revolution without Common Sense. This remains true even in our supposed post-literate meltdown—just look at Abundance, which inspired the creation of a Congressional caucus. That happened not because of Abundance the Podcast or Abundance the 7-Part YouTube Series, but because of Abundance the book.

A somewhat diminished readership can somewhat diminish the power of text in culture, but it’s a mistake to think that words only exercise influence over you when you behold those words firsthand. I’m reminded of Meryl Streep’s monologue in The Devil Wears Prada, when Anne Hathaway scoffs at two seemingly identical belts and Streep schools her:

...it’s sort of comical how you think that you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room.3

What’s true in the world of fashion is also true in the world of ideas. Being ignorant of the forces shaping society does not exempt you from their influence—it places you at their mercy. This is easy to miss. It may seem like ignorance is always overpowering knowledge, that the people who kick things down are triumphing over the people who build things up. That’s because kicking down is fast and loud, while building up is slow and quiet. But that is precisely why the builders ultimately prevail. The kickers get bored and wander off, while the builders return and start again.

I have one more gripe against the “death of literacy” hypothesis, and against Walter Ong, the Jesuit priest/English professor whose book Orality and Literacy provides the intellectual backbone for the argument.

Most of the differences between oral and literate cultures are actually differences between non-recorded and recorded cultures. And even if our culture has become slightly less literate, it has become far more recorded.

As Ong points out, in an oral culture, the only way for information to pass from one generation to another is for someone to remember and repeat it.4 This is bit like trying to maintain a music collection with nothing but a first-generation iPod: you can’t store that much, so you have to make tradeoffs. Oral traditions are chock full of repetition, archetypal characters, and intuitive ideas, because that’s what it takes to make something memorable. Precise facts, on the other hand, are like 10-gigabyte files—they’re going to get compressed, corrupted, or deleted.

Writing is one way of solving the storage problem, but it’s not the only way, and we use those other ways now more than ever. Humans took an estimated 2 trillion photos in 2025, and 20 million videos get uploaded to YouTube every day. No one knows how many spreadsheets, apps, or code files we make. Each one of these formats allows us to retain different kinds of information, and it causes us to think in a different register. What psychology is unlocked by Photoshop, iMovie, and Excel?

There is something unique about text, no doubt, and I’m sure a purely pictographic, videographic, or spreadsheet-graphic culture would be rather odd and probably dysfunctional. But having more methods of storage makes us better at transmitting knowledge, not worse, and they allow us to surpass the cognitive limits that so strongly shape oral culture.

Put another way: hearing a bard recite The Iliad around a campfire is nothing like streaming the song “Golden” on YouTube. That bard is going to add his own flourishes, he’s going to cut out the bits that might offend his audience, he’s probably going to misremember some stanzas, and no one will be able to fact-check him. In contrast, the billionth stream of “Golden” is exactly the same as the first. Even if people spend less time reading, it is impossible to return to a world where every fact that isn’t memorized is simply lost. I don’t believe we are nearly as close to a post-literate society as the critics think, but I also don’t believe that a post-literate society is going to bear much resemblance to a pre-literate society.

I have text on my mind right now for two reasons.

The first is that I’m writing a book, and it’s almost done. So maybe everything I’ve said is just motivated reasoning: “‘Books are very important!’ says man with book”.5 But the deeper I get, the more I read the thoughts that other people have tamed and transmuted into a form that could be fed into the printing press and the inkjet printer, and the more I try to do the same, the more I’m convinced that there is a power here that will persist.

The second reason is Experimental History just turned four. This is usually the time of year when I try to wax wise on the state of the blogosphere and the internet in general. So here’s my short report: it’s boom times for text.

I know that what we used to call “social media” is now just television you watch on your phone. I know that people want to spend their leisure time watching strangers apply makeup, assemble salads, and repair dishwashers. I know they want to see this guy dancing in his dirty bathroom and they want to watch Mr. Beast bury himself alive. These are their preferences, and woe betide anyone who tries to show them anything else, especially—God forbid—the written word.

But I also know that humans have a hunger that no video can satisfy. Even in the midst of infinite addictive entertainment, some people still want to read. A lot of people, in fact. I serve at their pleasure, and I am happy to, because I think the world ultimately belongs to them. 5,000 years after Sumerians started scratching cuneiform into clay and 600 years after Gutenberg started pressing inky blocks onto paper, text is still king. Long may it reign.

Here are last year’s most-viewed posts:

And here are my favorite MYSTERY POSTS that went out to paid subscribers only:

Thank you to everyone who makes Experimental History possible, including those who support the blog, and those who increase its power by yelling at it on the internet. Godspeed to all of you, and may your 2026 be too good for words.

By the way, here is the actual data on cigarette smoking, via the American Lung Association:

In case you’re wondering, the decline in smoking has not been offset by an increase in vaping. While adults vape a tiny bit more today than they did in 2019, the difference is very small:

It’s curious that the word “phubbing” (a combination of phone and snubbing) never caught on. Maybe that’s because it was coined by fiat: an advertising agency simply decided that’s what we should call it when someone ignores you and looks at their phone instead. If this word had bubbled up naturally from the crush of online discourse, maybe it would have gotten more buy-in, and maybe we’d be more sensitive to the phenomenon.

I know it might seem rich to quote a movie in a post that’s extolling text, but then Streep didn’t deliver her diatribe off the dome. Someone wrote it for her, and then she spoke it aloud. (And that script in turn was based on a novel.) It’s an obvious point, but when we’re decrying the death of literacy, it’s easy to forget that film is mainly a literate art form.

Improv comedy, in contrast, is a purely oral art form. And I can’t help but notice that film actors make millions and become world famous by speaking written words aloud, while improvisational actors never touch text at all and they mainly go into debt.

This isn’t completely true, of course—a parent can fashion a handaxe and hand it down to their child, thus transferring some handaxe-related knowledge. But lots of facts can’t be encoded in axes.

It comes out Spring 2027, so I’ll have more details then.

2026-01-07 00:45:44

Here’s the most replicated finding to come out of my area of psychology in the past decade: most people believe they suffer from a chronic case of awkwardness.

Study after study finds that people expect their conversations to go poorly, when in fact those conversations usually go pretty well. People assign themselves the majority of the blame for any awkward silences that arise, and they believe that they like other people more than other people like them in return. I’ve replicated this effect myself: I once ran a study where participants talked in groups of three, and then they reported/guessed how much each person liked each other person in the conversation. Those participants believed, on average, that they were the least liked person in the trio.

In another study, participants were asked to rate their skills on 20 everyday activities, and they scored themselves as better than average on 19 of them. When it came to cooking, cleaning, shopping, eating, sleeping, reading, etc., participants were like, “Yeah, that’s kinda my thing.” The one exception? “Initiating and sustaining rewarding conversation at a cocktail party, dinner party, or similar social event”.

I find all this heartbreaking, because studies consistently show that the thing that makes humans the happiest is positive relationships with other humans. Awkwardness puts a persistent bit of distance between us and the good life, like being celiac in a world where every dish has a dash of gluten in it.

Even worse, nobody seems to have any solutions, nor any plans for inventing them. If you want to lose weight, buy a house, or take a trip to Tahiti, entire industries are waiting to serve you. If you have diagnosable social anxiety, your insurance might pay for you to take an antidepressant and talk to a therapist. But if you simply want to gain a bit of social grace, you’re pretty much outta luck. It’s as if we all think awkwardness is a kind of moral failing, a choice, or a congenital affliction that suggests you were naughty in a past life—at any rate, unworthy of treatment and undeserving of assistance.

We can do better. And we can start by realizing that, even though we use one word to describe it, awkwardness is not one thing. It’s got layers, like a big, ungainly onion. Three layers, to be exact. So to shrink the onion, you have to peel it from the skin to the pith, adapting your technique as you go, because removing each layer requires its own unique technique.

Before we make our initial incision, I should mention that I’m not the kind of psychologist who treats people. I’m the kind of psychologist who asks people stupid questions and then makes sweeping generalizations about them. You should take everything I say with a heaping teaspoon of salt, which will also come in handy after we’ve sliced the onion and it’s time to sauté it. That disclaimer disclaimed, let’s begin on the outside and work our way in, starting with—

The outermost layer of the awkward onion is the most noticeable one: awkward people do the wrong thing at the wrong time. You try to make people laugh; you make them cringe instead. You try to compliment them; you creep them out. You open up; you scare them off. Let’s call this social clumsiness.

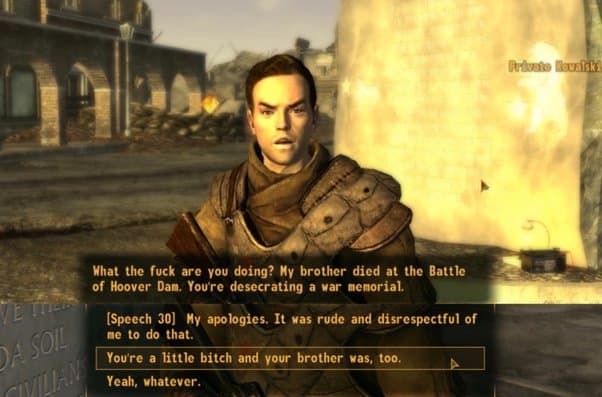

Being socially clumsy is like being in a role-playing game where your charisma stat is chronically too low and you can’t access the correct dialogue options. And if you understand that reference, I understand why you’re reading this post.

Here’s the bad news: I don’t think there’s a cure for clumsiness. Every human trait is normally distributed, so it’s inevitable that some chunk of humanity is going to have a hard time reading emotional cues and predicting the social outcomes of their actions. I’ve seen high-functioning, socially ham-handed people try to memorize interpersonal rules the same way chess grandmasters memorize openings, but it always comes off stilted and strange. You’ll be like, “Hey, how you doing” and they’re like “ROOK TO E4, KNIGHT TO C11, QUEEN TO G6” and you’re like “uhhh cool man me too”.

Here’s the good news, though: even if you can’t cure social clumsiness, there is a way to manage its symptoms. To show you how, let me tell you a story of a stupid thing I did, and what I should have done instead.

Once, in high school, I was in my bedroom when I saw a girl in my class drive up to the intersection outside my house. It was dark outside and I had the light on, and so when she looked up, she caught me in the mortifying act of, I guess, existing inside my home? This felt excruciatingly embarrassing, for some reason, and so I immediately dropped to the floor, as if I was in a platoon of GIs and someone had just shouted “SNIPER!” But breaking line of sight doesn’t cause someone to unsee you, and so from this girl’s point of view, she had just locked eyes with some dude from school through a window and his response had been to duck and cover. She told her friends about this, and they all made fun of me ruthlessly.

I learned an important lesson that day: when it comes to being awkward, the coverup is always worse than the crime. If you just did something embarrassing mere moments ago, it’s unlikely that you have suddenly become socially omnipotent and that all of your subsequent moves are guaranteed to be prudent and effective. It’s more likely that you’re panicking, and so your next action is going to be even stupider than your last.

And that, I think, is the key to mitigating your social clumsiness: give up on the coverups. When you miss a cue or make a faux pas, you just have to own it. Apologize if necessary, make amends, explain yourself, but do not attempt to undo your blunder with another round of blundering. If you knock over a stack of porcelain plates, don’t try to quickly sweep up the shards before anyone notices; you will merely knock over a shelf of water pitchers.

This turns out to be a surprisingly high-status move, because when you readily admit your mistakes, you imply that you don’t expect to be seriously harmed by them, and this makes you seem intimidating and cool. You know how when a toddler topples over, they’ll immediately look at you to gauge how upset they should be? Adults do that too. Whenever someone does something unexpected, we check their reaction—if they look embarrassed, then whatever they did must be embarrassing. When that person panics, they look like a putz. When they shrug and go, “Classic me!”, they come off as a lovable doof, or even, somehow, a chill, confident person.

In fact, the most successful socially clumsy people I know can manage their mistakes before they even happen. They simply own up to their difficulties and ask people to meet them halfway, saying things like:

Thanks for inviting me over to your house. It’s hard for me to tell when people want to stop hanging out with me, so please just tell me when you’d like me to leave. I won’t be mad. If it’s weird to you, I’m sorry about that. I promise it’s not weird to me.

It takes me a while to trust people who attempt this kind of social maneuver—they can’t be serious, can they? But once I’m convinced they’re earnest, knowing someone’s social deficits feels no different than knowing their dietary restrictions (“Arthur can’t eat artichokes; Maya doesn’t understand sarcasm”), and we get along swimmingly. Such a person is always going to seem a bit like a Martian, but that’s fine, because they are a bit of a Martian, and there’s nothing wrong with being from outer space as long as you’re upfront about it.

When we describe someone else as awkward, we’re referring to the things they do. But when we describe ourselves as awkward, we’re also referring to this whole awkward world inside our heads, this constant sensation that you’re not slotted in, that you’re being weird, somehow. It’s that nagging thought of “does my sweater look bad” that blossoms into “oh god, everyone is staring at my horrible sweater” and finally arrives at “I need to throw this sweater into a dumpster immediately, preferably with me wearing it”.

This is the second layer of the awkward onion, one that we can call excessive self-awareness. Whether you’re socially clumsy or not, you can certainly worry that you are, and you can try to prevent any gaffes from happening by paying extremely close attention to yourself at all times. This strategy always backfires because it causes a syndrome that athletes call “choking” or “the yips”—that stilted, clunky movement you get when you pay too much attention to something that’s supposed to be done without thinking. As the old poem goes:

A centipede was happy – quite!

Until a toad in fun

Said, “Pray, which leg moves after which?”

This raised her doubts to such a pitch,

She fell exhausted in the ditch

Not knowing how to run.

The solution to excessive self-awareness is to turn your attention outward instead of inward. You cannot out-shout your inner critic; you have to drown it out with another voice entirely. Luckily, there are other voices around you all the time, emanating from other humans. The more you pay attention to what they’re doing and saying, the less attention you have left to lavish on yourself.

You can call this mindfulness if that makes it more useful to you, but I don’t mean it as a sort of droopy-eyed, slack-jawed, I-am-one-with-the-universe state of enlightenment. What I mean is: look around you! Human beings are the most entertaining organisms on the planet. See their strange activities and their odd proclivities, their opinions and their words and their what-have-you. This one is riding a unicycle! That one is picking their nose and hoping no one notices! You’re telling me that you’d rather think about yourself all the time?

Getting out of your own head and into someone else’s can be surprisingly rewarding for all involved. It’s hard to maintain both an internal and an external dialogue simultaneously, and so when your self-focus is going full-blast, your conversations degenerate into a series of false starts (“So...how many cousins do you have?” “Seven.” “Ah, a prime number.”) Meanwhile, the other person stays buttoned up because, well, why would you disrobe for someone who isn’t even looking? Paying attention to a human, on the other hand, is like watering a plant: it makes them bloom. People love it when you listen and respond to them, just like babies love it when they turn a crank and Elmo pops out of a box—oh! The joy of having an effect on the world!

Of course, you might not like everyone that you attend to. When people start blooming in your presence, you’ll discover that some of them make you sneeze, and some of them smell like that kind of plant that gives off the stench of rotten eggs. But this is still progress, because in the Great Hierarchy of Subjective Experiences, annoyance is better than awkwardness—you can walk away from an annoyance, but awkwardness comes with you wherever you go.

It can be helpful to develop a distaste for your own excessive self-focus, and one way to do that is to relabel it as “narcissism”. We usually picture narcissists as people with an inflated sense of self worth, and of course many narcissists are like that. But I contend that there is a negative form of narcissism, one where you pay yourself an extravagant amount of attention that just happens to come in the form of scorn. Ultimately, self-love and self-hate are both forms of self-obsession.

So if you find yourself fixated on your own flaws, perhaps its worth asking: what makes you so worthy of your own attention, even if it’s mainly disapproving? Why should you be the protagonist of every social encounter? If you’re really as bad as you say, why not stop thinking about yourself so much and give someone else a turn?

Social clumsiness is the thing that we fear doing, and excessive self-focus is the strategy we use to prevent that fear from becoming real, but neither of them is the fear itself, the fear of being left out, called out, ridiculed, or rejected. “Social anxiety” is already taken, so let’s refer to this center of the awkward onion as people-phobia.

People-phobia is both different from and worse than all other phobias, because the thing that scares the bajeezus out of you is also the thing you love the most. Arachnophobes don’t have to work for, ride buses full of, or go on first dates with spiders. But people-phobes must find a way to survive in a world that’s chockablock with homo sapiens, and so they yo-yo between the torment of trying to approach other people and the agony of trying to avoid them.

At the heart of people-phobia are two big truths and one big lie. The two big truths: our social connections do matter a lot, and social ruptures do cause a lot of pain. Individual humans cannot survive long on their own, and so evolution endowed us with a healthy fear of getting voted off the island. That’s why it hurts so bad to get bullied, dumped, pantsed, and demoted, even though none of those things cause actual tissue damage.1

But here’s the big lie: people-phobes implicitly believe that hurt can never be healed, so it must be avoided at all costs. This fear is misguided because the mind can, in fact, mend itself. Just like we have a physical immune system that repairs injuries to the body, we also have a psychological immune system that repairs injuries to the ego. Black eyes, stubbed toes, and twisted ankles tend to heal themselves on their own, and so do slip-ups, mishaps, and faux pas.

That means you can cure people-phobia the same way you cure any fear—by facing it, feeling it, and forgetting it. That’s the logic behind exposure and response prevention: you sit in the presence of the scary thing without deploying your usual coping mechanisms (scrolling on your phone, fleeing, etc.) and you do this until you get tired of being scared. If you’re an arachnophobe, for instance, you peer at a spider from a safe distance, you wait until your heart rate returns to normal, you take one step closer, and you repeat until you’re so close to the spider that it agrees to officiate your wedding.2

Unfortunately, people-phobia is harder to treat than arachnophobia because people, unlike spiders, cannot be placed in a terrarium and kept safely on the other side of the room. There is no zero-risk social interaction—anyone, at any time, can decide that they don’t like you. That’s why your people-phobia does not go into spontaneous remission from continued contact with humanity: if you don’t confront your fear in a way that ultimately renders it dull, you’re simply stoking the phobia rather than extinguishing it.3

Exposure only works for people-phobia, then, if you’re able to do two things: notch some pleasant interactions and reflect on them afterward. The notching might sound harder than the reflecting, but the evidence suggests it’s actually the other way around. Most people have mostly good interactions most of the time. They just don’t notice.

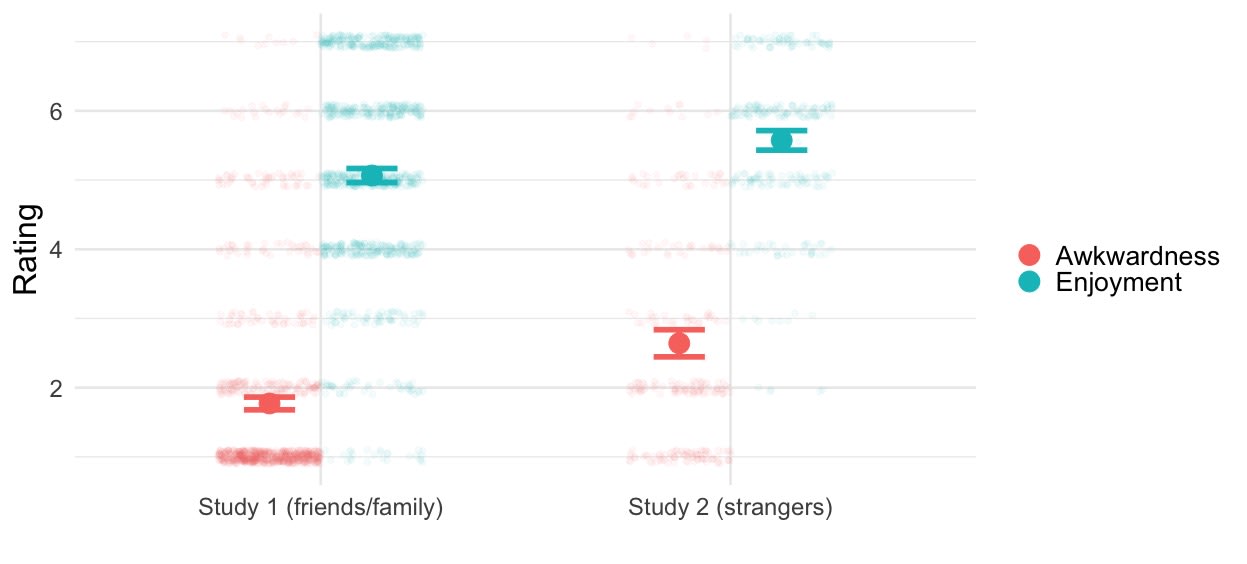

In any study I’ve ever read and in every study I’ve ever conducted myself, when you ask people to report on their conversation right after the fact, they go, “Oh, it was pretty good!”. In one study, I put strangers in an empty room and told them to talk about whatever they want for as long as they want, which sounds like the social equivalent of being told to go walk on hot coals or stick needles in your eyes. And yet, surprisingly, most of those participants reported having a perfectly enjoyable, not-very-awkward time. When I asked another group of participants to think back to their most recent conversation (which were overwhelmingly with friends and family, rather than strangers), I found the same pattern of results4:

But when you ask people to predict their next conversation, they suddenly change their tune. I had another group of participants guess how this whole “meet a stranger in the lab, have an open-ended conversation” thing would go, and they were not optimistic. Participants estimated that only 50% of conversations would make it past five minutes (actually, 87% did), and that only 15% of conversations would go all the way to the time limit of 45 minutes (actually, 31% did). So when people meet someone new, they go, “that was pretty good!”, but when they imagine meeting someone new, they go, “that will be pretty bad!”

A first-line remedy for people-phobia, then, is to rub your nose in the pleasantness of your everyday interactions. If you’re afraid that your goof-ups will doom you to a lifetime of solitude and then that just...doesn’t happen, perhaps it’s worth reflecting on that fact until your expectations update to match your experiences. Do that enough, and maybe your worries will start to appear not only false, but also tedious. However, if reflecting on the contents of your conversations makes you feel like that guy in Indiana Jones who gets his face melted off when he looks directly at the Ark of the Covenant, then I’m afraid you’re going to need bigger guns than can fit into a blog post.

Obviously, I don’t think you can instantly de-awkward yourself by reading the right words in the right order. We’re trying to override automatic responses and perform laser removal on burned-in fears—this stuff takes time.

In the meantime, though, there’s something all of us can do right away: we can disarm. The greatest delusion of the awkward person is that they can never harm someone else; they can only be harmed. But every social hangup we have was hung there by someone else, probably by someone who didn’t realize they were hanging it, maybe by someone who didn’t even realize they were capable of such a thing. When Todd Posner told me in college that I have a big nose, did he realize he was giving me a lifelong complex? No, he probably went right back to thinking about his own embarrassingly girthy neck, which, combined with his penchant for wearing suits, caused people to refer to him behind his back as “Business Frog” (a fact I kept nobly to myself).

So even if you can’t rid yourself of your own awkward onion, you can at least refrain from fertilizing anyone else’s. This requires some virtuous sacrifice, because the most tempting way to cope with awkwardness is to pass it on—if you’re pointing and laughing at someone else, it’s hard for anyone to point and laugh at you. But every time you accept the opportunity to be cruel, you increase the ambient level of cruelty in the world, which makes all of us more likely to end up on the wrong end of a pointed finger.

All of that is to say: if you happen to stop at an intersection and you look up and see someone you know just standing there inside his house he immediately ducks out of sight, you can think to yourself, “There are many reasonable explanations for such behavior—perhaps he just saw a dime on the floor and bent down to get it!” and you can forget about the whole ordeal and, most importantly, keep your damn eyes on the road.

PS: This post pairs well with Good Conversations Have Lots of Doorknobs.

Psychologists who study social exclusion love to use this horrible experimental procedure called “Cyberball”, where you play a game of virtual catch with two other participants. Everything goes normally at first, but then the other participants inexplicably start throwing the ball only to each other, excluding you entirely. (In reality, there are no other participants; this is all pre-programmed.) When you do this to someone who’s in an fMRI scanner, you can see that getting ignored in Cyberball lights up the same part of the brain that processes physical pain. But you don’t need a big magnet to find this effect: just watching the little avatars ignore you while tossing the ball back and forth between them will immediately make you feel awful.

My PhD cohort included some clinical psychologists who interned at an OCD treatment center as part of their training. Some patients there had extreme fears about wanting to harm other people—they didn’t actually want to hurt anybody, but they were afraid that they did. So part of their treatment was being given the opportunity to cause harm, and to realize that they weren’t really going to do it. At the final stage of this treatment, patients are given a knife and told to hold it at their therapist’s throat, who says, “See? Nothing bad is happening.” Apparently this procedure is super effective and no one at the clinic had ever been harmed doing it, but please do not try this at home.

As this Reddit thread so poetically puts it, “you have to do exposure therapy right otherwise you’re not doing exposure therapy, you’re doing trauma.”

You might notice that while awkwardness ratings are higher when people talk to strangers vs. loved ones, enjoyment ratings are higher too. What gives? One possibility is that people are “on” when they meet someone new, and that’s a surprisingly enjoyable state to be in. That’s consistent with this study from 2010, which found that:

Participants actually had a better time talking to a stranger than they did talking to their romantic partner.

When they were told to “try to make a good impression” while talking to their romantic partner (“Don’t role-play, or pretend you are somewhere where you are not, but simply try to put your best face forward”), they had a better time than when they were given no such instructions.

Participants failed to predict both of these effects.

Like most psychology studies published around this time, the sample sizes and effects are not huge, so I wouldn’t be surprised if you re-ran this study and found no effect. But even if people enjoyed talking to strangers as much as they enjoy talking to their boyfriends and girlfriends, that would still be pretty surprising.

2025-12-10 01:46:17

All of us, whether we realize it or not, are asking ourselves one question over and over for our whole lives: how much should I suffer?

Should I take the job that pays more but also sucks more? Should I stick with the guy who sometimes drives me insane? Should I drag myself through an organic chemistry class if I means I have a shot at becoming a surgeon?

It’s impossible to answer these questions if you haven’t figured out your Acceptable Suffering Ratio. I don’t know how one does that in general. I only know how I found mine: by taking a dangerous, but legal, drug.

I’ve always had bad skin. I was that kinda pimply kid in school—you know him, that kid with a face that invites mild cruelty from his fellow teens.1 I did all sorts of scrubs and washes, to little avail. In grad school, I started getting nasty cysts in my earlobes that would fill with pus and weep for days and I decided: enough. Enough! It’s the 21st century. Surely science can do something for me, right?

And science could do something for me: it could offer me a drug called Accutane. Well, it could offer me isotretinoin, which used to be sold as Accutane, but the manufacturers stopped selling it because too many kids killed themselves.

See, Accutane has a lot of potential side effects, including hearing loss, pancreatitis, “loosening of the skin”, “increased pressure around the brain”, and, most famous of all, depression, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide and self-injury. In 2000, a Congressman’s son shot himself while he was on Accutane, which naturally made everyone very nervous. My doctor was so worried that she offered to “balance me out” with an antidepressant before I even started on the acne meds. I turned her down, figuring I was too young to try the “put a bunch of drugs inside you and let ‘em duke it out” school of pharmacology.

But her concerns were reasonable: Accutane did indeed make me less happy. Like an Instagram filter for the mind, it deepened the blacks and washed out the whites: sad things felt a little sharper and happy things felt a little blunted. I was a bit quicker to get angry, and I was more often visited by the thought that nothing in my life was going well—although, as a grad student, I was visited fairly often by that thought even in normal times. It wasn’t the kind of thing I noticed every day. But occasionally, when I was, say, struggling to get some code to work, I’d feel an extra, unfamiliar tang of despair, and I’d go, “Accutane, is that you?”

The drugs also made my skin like 95% better. It was night and day—we’re talking going from Diary of a Pimply Kid to uh, Diary of a Normal Kid. That wonderful facial glow-up that most people experience as they exit puberty, I got to experience that same thing in my mid-20s. Ten years later, I’m still basically zit-free.

I didn’t realize it at first, but I had found my Acceptable Suffering Ratio. Six months of moderate sadness for a lifetime of clear skin? Yes, I’ll take that deal. But nothing worse than that. If the suffering is longer or deeper, if the upside is lower or less certain: no way dude. I’m looking for Accutane-level value out of life, or better.

That probably sounds stupid. It is stupid. And yet, until that point, I don’t think I was sufficiently skeptical of the deals life was offering me. Whenever I had the chance to trade pain for gain, I wasn’t asking: how bad, for how long, and for how much in return? I literally never wondered “How much should I suffer to achieve my goals?” because the implicit answer was always “As much as I have to”.

My oversight makes some sense—I was in academia at the time, where guaranteed suffering for uncertain gains is the name of the game. But I think a lot of us have Acceptable Suffering Ratios that are way out of whack. We believe ourselves to be in the myth of Sisyphus, where suffering is both futile and inescapable, when we are actually in myth of Hercules, where heroic labors ought to earn us godly rewards.

For example, I know this guy, call him Omar, and women are always falling in unrequited love with him. They’re gaga for Omar, but he’s lukewarm on them, and so they make a home for him in their hearts that he only ever uses as a crash pad. I don’t know these women personally, but sometimes I wish I could go undercover in their lives as like their hairdresser or whatever just so I could tell them: “It’s not supposed to feel like this.” This pining after nothing, this endless waiting and hoping that some dude’s change of heart will ultimately vindicate your years of one-sided affection—that’s not the trade that real love should ask of you.

Real love does bring plenty of pain: the angst of being perceived exactly as you are, the torment of confronting your own selfishness, the fear of giving someone else the nuclear detonation codes to your life. But if you can withstand those agonies, you will be richly rewarded. Omar’s frustrated lovers have this romantic notion that love is a burden to be borne, and the greater the burden, the greater the love. When a love is right, though, it’s less like heaving a legendary boulder up a mountain, and more like schlepping a picnic basket up a hill—yes, you gotta carry the thing to and fro, and it’s a bit of a pain in the ass, but in between you get to enjoy the sunset and the brie.

Our Acceptable Suffering Ratios are most out of whack when it comes to choosing what to do with our lives.

Careers usually have a “pay your dues” phase, which implies the existence of a “collect your dues” phase. In my experience, however, the dues that go in are no guarantee of the dues that come back out. There is no cosmic, omnipotent bean-counter who makes sure that you get your adversity paid back with interest. You really can suffer for nothing.

If you’re staring down a gauntlet of pain, then, it’s important to peek at the people coming out the other side. If they’re like, “I’m so glad I went through that gauntlet of pain! That was definitely worth it, no question!” then maybe it’s wise to follow in their footsteps. But if the people on the other side of the gauntlet are like, “What do you mean, other side of the gauntlet? I’m still in it! Look at me suffering!”, perhaps you should steer clear.

Psychologists refer to this process of gauntlet-peeking as surrogation. People are hesitant to do it, however, I think because it feels so silly. If you see people queuing up for a gauntlet of pain, it’s natural to assume that the payoff must be worth the price. But that’s reasoning in the wrong direction. We shouldn’t be asking, “How desirable is this job to the people who want it?” That answer is always going to be “very desirable”, because we’ve selected on the outcome. Instead, the thing we need to know is, “How desirable is this job to the people who have it?”

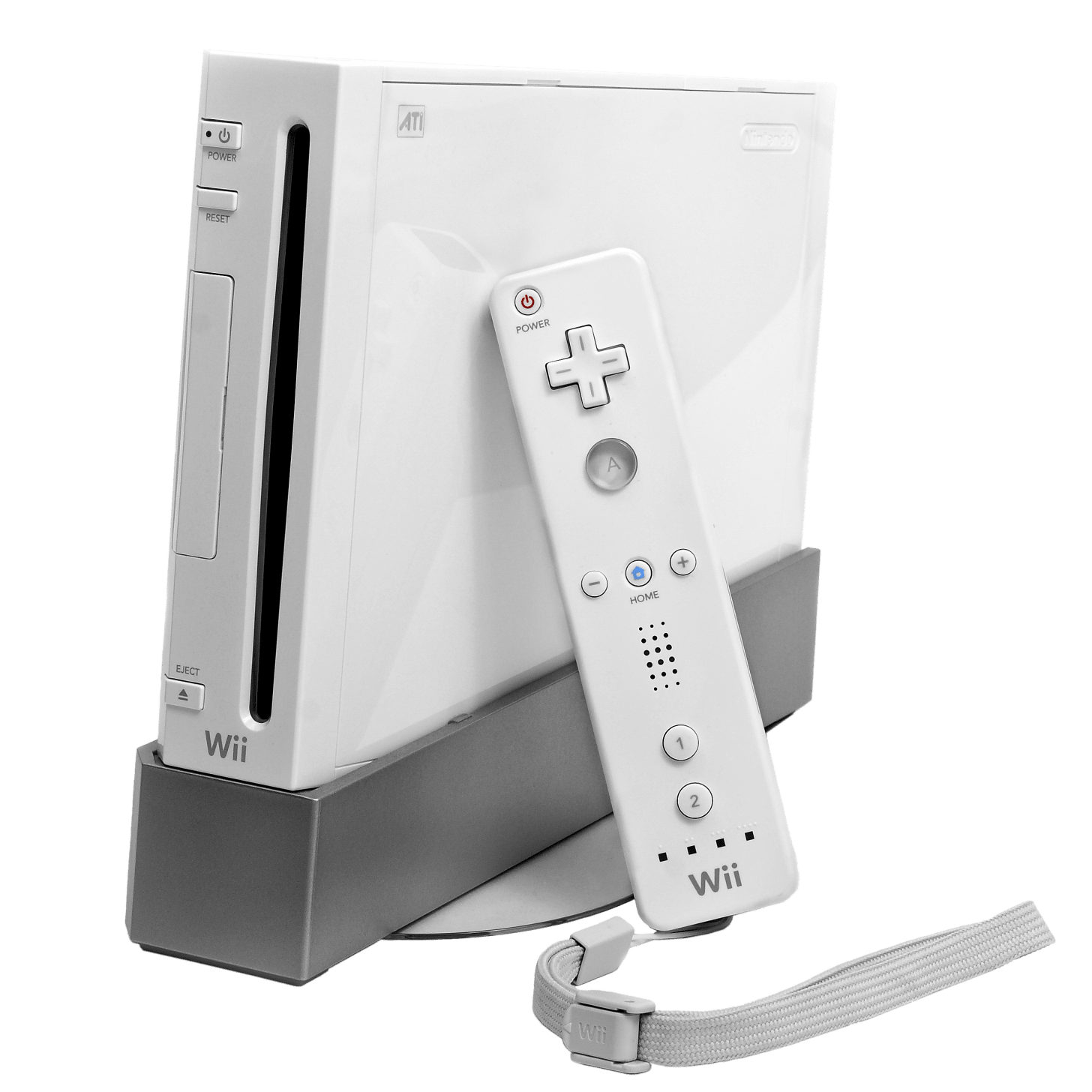

It turns out the scarcity of a resource is much more potent in the wanting than it is in the having. I had a chance to learn this lesson about twenty years ago, when the stakes were far lower, but I declined. Back then, I thought the only barrier between me and permanent happiness was a Nintendo Wii. I stood outside a Target at 5am in the freezing cold for the mere chance of buying one, counting and re-counting the people in front of me, desperately trying to guess whether there would be enough Wiis to go around, my face going numb as I dreamed of the rapturous enjoyment of Wii Bowling.

I didn’t realize that, by the time I got home, the most exciting part of owning a Wii was already over. When I strapped on my Wii-mote, there was not a gaggle of covetous boys salivating outside my window, reminding me that I was having an enviable experience. It turns out that what makes a game fun is its quality, not its rarity.

If I had understood that obvious fact at the time, I probably wouldn’t have wasted so many hours lusting after a game console, caressing pictures of nunchuck attachments in my monthly Nintendo Power, calling Best Buys to pump them for information about when shipments would arrive, or guilting my mom into pre-dawn excursions to far-flung electronics stores.

Post-Accutane, though, I think I got better at spotting situations like these and surrogating myself out of them. When I got to be an upper-level PhD student, I would go to conferences, look for the people who were five years or so ahead of me, and ask myself: do they seem happy? Do I want to be like them? Are they pleased to have exited the gauntlet of pain that separates my life and theirs? The answer was an emphatic no. Landing a professor position had not suddenly put all their neuroses into remission. If anything, their success had justified their suffering, thus inviting even more of it. If it took this much self-abnegation, mortification, and degradation to get an academic job, imagine how much you’ll need for tenure!

I think our dysfunctional relationship with suffering is wired deep in our psyches, because it shows up even in the midst of our fantasies.