2026-03-13 23:15:50

Lilypond is a TeX-like typesetting language for sheet music. I’ve had good results asking AI to generate Lilypond code, which is surprising given the obscurity of the language. There can’t be that much publicly available Lilypond code to train on.

I’ve mostly generated Lilypond code for posts related to music theory, such as the post on the James Bond chord. I was curious how well AI would work if I uploaded an image of sheet music and asked it to produce corresponding Lilypond code.

In a nutshell, the results were hilariously bad as far as the sheet music produced. But Grok did a good job of recognizing the source of the clips.

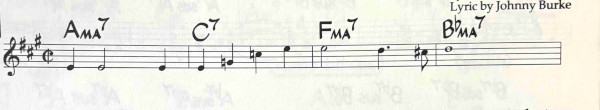

Here are the two images I used, one of classical music

and one of jazz.

I used the same prompt for both images with Grok and ChatGPT: Write Lilypond code corresponding to the attached sheet music image.

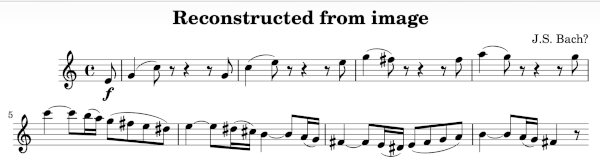

Here’s what I got when I compiled the code Grok generated for the first image.

This bears no resemblance to the original, turning one measure into eight. However, Grok correctly inferred that the excerpt was by Bach, and the music it composed (!) is in the style of Bach, though it is not at all what I asked for.

Here’s the corresponding output from ChatGPT.

Not only did ChatGPT hallucinate, it hallucinated in two-part harmony!

One reason I wanted to try a jazz example was to see what would happen with the chord symbols.

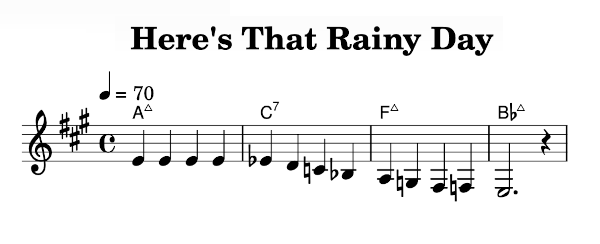

Here’s what Grok did with the second sheet music image.

The notes are almost unrelated to the original, though the chords are correct. The only difference is that Grok uses the notation Δ for a major 7th chord; both notations are common. And Grok correctly inferred the title of the song.

I edited the image above. I didn’t change any notes, but I moved the title to center it over the music. I also cut out the music and lyrics credits to make the image fit on the page easier. Grok correctly credited Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen for the lyrics and music.

Here’s what I got when I compiled the Lilypond code that ChatGPT produced. The chords are correct, as above. The notes bear some similarity to the original, though ChatGPT took the liberty of changing the key and the time signature, and the last measure has seven and a half beats.

ChatGPT did not speculate on the origin of the clip, but when I asked “What song is this music from?” it responded with “The fragment appears to be from the jazz standard ‘Misty.'”

The post Typesetting sheet music with AI first appeared on John D. Cook.2026-03-13 00:37:46

In the previous two posts, we looked at why Mathematica and SymPy did not simplify sinh(arccosh(x)) to √(x² − 1) as one might expect. After understanding why sinh(arccosh(x)) doesn’t simplify nicely, it’s natural to ask why sin(arccos(x)) does simplify nicely.

In this post I sketched a proof of several identities including

sin(arccos(x)) = √(1 − x²)

saying the identities could be proved geometrically. Let x be between 0 and 1. Construct right triangle with hypotenuse of length 1 and one side of length x. Call the acute angle formed by these two sides θ. Then cos θ = x, and so arccos(x) = θ, and sin θ = √(1 − x²). This proves the identity above, but only for 0 < x < 1.

If we make branch cuts along (−∞, −1] and [1, ∞) we can extend arccos(z) uniquely by analytic continuation. We can extend the definition to the branch cuts by continuity, but from one direction. We either have to choose the extension to be continuous from above the branch cuts or from below; we have to choose one or the other because the two limits are not equal. As far as I know, everyone chooses continuity from above, i.e. continuity with quadrant II, by convention.

In any case, we can define arccos(z) for any complex number z, and the result is a number whose cosine is z. Therefore the square of its cosine is z², and the square of its sine is 1 − z². So we have

sin²(arccos(z)) = 1 − z².

But does that mean

sin(arccos(z)) = √(1 − z²)?

Certainly it does if we’re working with real numbers, but does it for complex numbers?

Recall what square root means for complex numbers: it is the analytic function with branch cut (−∞, 0] that agrees with the real square root function along the real line, and is defined along the branch cut to be continuous with quadrant II. Since

sin(arccos(z)) = √(1 − z²)

for real −1 < z < 1, the two sides of the equation are equal on a set with a limit point, and so as analytical functions they are equal on their common domain.

The only remaining detail is whether the two functions are equal along the branch cut (−∞, −1] where we’ve extended the function by continuity. As

Since we’ve defined both the arccos and square root functions by continuous extension from the second quadrant, equality on the branch cut also follows by continuity.

The post Inverse cosine first appeared on John D. Cook.2026-03-11 00:08:15

The previous post looked at why Mathematica does not simplify the expression Sinh[ArcCosh[x]] the way you might think it should. This post will be a sort of Python analog of the previous post.

SymPy is a Python library that among other things will simplify mathematical expressions. As before, we seek to verify the entries in the table below, this time using SymPy.

Here’s the code:

from sympy import *

x = symbols('x')

print( simplify(sinh(asinh(x))) )

print( simplify(sinh(acosh(x))) )

print( simplify(sinh(atanh(x))) )

print( simplify(cosh(asinh(x))) )

print( simplify(cosh(acosh(x))) )

print( simplify(cosh(atanh(x))) )

print( simplify(tanh(asinh(x))) )

print( simplify(tanh(acosh(x))) )

print( simplify(tanh(atanh(x))) )

As before, the results are mostly as we’d expect:

x sqrt(x - 1)*sqrt(x + 1) x/sqrt(1 - x**2) sqrt(x**2 + 1) x 1/sqrt(1 - x**2) x/sqrt(x**2 + 1) sqrt(x - 1)*sqrt(x + 1)/x x

Also as before, sinh(acosh(x)) and tanh(acosh(x)) return more complicated expressions than in the table above. Why doesn’t

√(x − 1) √(x + 1)

simplify to

√(x² − 1)

as you’d expect? Because the equation

√(x − 1) √(x + 1) = √(x² − 1)

does not hold for all x. See the previous post for the subtleties of defining arccosh and sqrt for complex numbers. The equation above does not hold, for example, when x = −2.

As in Mathematica, you can specify the range of variables in SymPy. If we specify that x ≥ 0 we get the result we expect. The code

x = symbols('x', real=True, nonnegative=True)

print( simplify(sinh(acosh(x))) )

prints

sqrt(x**2 - 1)

as expected.

The post Simplifying expressions in SymPy first appeared on John D. Cook.2026-03-10 23:12:03

I’ve written several posts about applying trig functions to inverse trig functions. I intended to write two posts, one about the three basic trig functions and one about their hyperbolic counterparts. But there’s more to explore here than I thought at first. For example, the mistakes that I made in the first post lead to a couple more posts discussing error detection and proofs.

I was curious about how Mathematica would handle these identities. Sometimes it doesn’t simplify expressions the way you expect, and for interesting reasons. It handled the circular functions as you might expect.

So, for example, if you enter Sin[ArcCos[x]] it returns √(1 − x²) as in the table above. Then I added an h on the end of all the function names to see whether it would reproduce the table of hyperbolic compositions.

For the most part it did, but not entirely. The results were as expected except when applying sinh or cosh to arccosh. But Sinh[ArcCosh[x]] returns

and Tanh[ArcCosh[x]] returns

Why didn’t Sinh[ ArcCosh[x] ] just return √(x² − 1)? The expression it returned is equivalent to this: just square the (x + 1) term, bring it inside the radical, and simplify. That line of reasoning is correct for some values of x but not for others. For example, Sinh[ArcCosh[2]] returns −√3 but √(3² − 1) = √3. The expression Mathematica returns for Sinh[ArcCosh[x]] correctly evaluates to −√3.

To understand what’s going on, we have to look closer at what arccosh(x) means. You might say it is a function that returns the number whose hyperbolic cosine equals x. But cosh is an even function: cosh(−x) = cosh(x), so we can’t say the value. OK, so we define arccosh(x) to be the positive number whose hyperbolic cosine equals x. That works for real values of x that are at least 1. But what do we mean by, for example, arccosh(1/2)? There is no real number y such that cosh(y) = 1/2.

To rigorously define inverse hyperbolic cosine, we need to make a branch cut. We cannot define arccosh as an analytic function over the entire complex plane. But if we remove (−∞, 1], we can. We define arccosh(x) for real x > 1 to be the positive real number y such that cosh(y) = x, and define it for the rest of the complex plane (with our branch cut (−∞, 1] removed) by analytic continuation.

If we look up ArcCosh in Mathematica’s documentation, it says “ArcCosh[z] has a branch cut discontinuity in the complex z plane running from −∞ to +1.” But what about values of x that lie on the branch cut? For example, we looked at ArcCosh[-2] above. We can extend arccosh to the entire complex plane, but we cannot extend it as an analytic function.

So how do we define arccosh(x) for x in (−∞, 1]? We could define it to be the limit of arccosh(z) as z approaches x for values of z not on the branch cut. But we have to make a choice: do we approach x from above or from below? That is, we can define arccosh(x) for real x ≤ 1 by

or by

but we have to make a choice because the two limits are not the same. For example, Sinh[ArcCosh[-2 + 0.001 I]] returns 11.214 + 2.89845 I but Sinh[ArcCosh[-2 + 0.001 I]] returns 11.214 - 2.89845 I. By convention, we choose the limit from above.

Where did we go wrong when we assumed Mathematica’s expression for sinh(arccosh(x))

could be simplified to √(x² − 1)? We implicitly assumed √(x + 1)² = (x + 1). And that’s true, if x ≥ − 1, but not for smaller x. Just as we have be careful about how we define arccosh, we have to be careful about how we define square root.

The process of defining the square root function for all complex numbers is analogous to the process of defining arccosh. First, we define square root to be what we expect for positive real numbers. Then we make a branch cut, in this case (−∞, 0]. Then we define it by analytic continuation for all values not on the cut. Then finally, we define it along the cut by continuity, taking the limit from above.

Once we’ve defined arccosh and square root carefully, we can see that the expressions Mathematica returns for sinh(arccosh(x)) and tanh(arccosh(x)) are correct for all complex inputs, while the simpler expressions in the table above implicitly assume we’re working with values of x for which arccosh(x) is real.

If we are only concerned with values of x ≥ − 1 we can tell Mathematica this, and it will simplify expressions accordingly. If we ask it for

Simplify[Sinh[ArcCosh[x]], Assumptions -> {x >= -1}]

it will return √(x² − 1).

2026-03-10 06:16:09

I’ve written a couple posts that reference the table below.

You could make a larger table, 6 × 6, by including sec, csc, cot, and their inverses, as Baker did in his article [1].

Note that rows 4, 5, and 6 are the reciprocals of rows 1, 2, and 3.

Returning to the theme of the previous post, how could we verify that the expressions in the table are correct? Each expression is one of 14 forms for reasons we’ll explain shortly. To prove that the expression in each cell is the correct one, it is sufficient to check equality at just one random point.

Every identity can be proved by referring to a right triangle with one side of length x, one side of length 1, and the remaining side of whatever length Pythagoras dictates, just as in the first post [2]. Define the sets A, B, and C by

A = {1}

B = {x}

C = {√(1 − x²), √(x² − 1), √(1 + x²)}

Every expression is the ratio of an element from one of these sets and an element of another of these sets. You can check that this can be done 14 ways.

Some of the 14 functions are defined for |x| ≤ 1, some for |x| ≥, and some for all x. This is because sin and cos has range [−1, 1], sec and csc have range (−∞, 1] ∪ [1, ∞) and tan and cot have range (−∞, ∞). No two of the 14 functions are defined and have the same value at more than a point or two.

The follow code verifies the identities at a random point. Note that we had to define a few functions that are not built into Python’s math module.

from math import *

def compare(x, y):

print(abs(x - y) < 1e-12)

sec = lambda x: 1/cos(x)

csc = lambda x: 1/sin(x)

cot = lambda x: 1/tan(x)

asec = lambda x: atan(sqrt(x**2 - 1))

acsc = lambda x: atan(1/sqrt(x**2 - 1))

acot = lambda x: pi/2 - atan(x)

x = np.random.random()

compare(sin(acos(x)), sqrt(1 - x**2))

compare(sin(atan(x)), x/sqrt(1 + x**2))

compare(sin(acot(x)), 1/sqrt(x**2 + 1))

compare(cos(asin(x)), sqrt(1 - x**2))

compare(cos(atan(x)), 1/sqrt(1 + x**2))

compare(cos(acot(x)), x/sqrt(1 + x**2))

compare(tan(asin(x)), x/sqrt(1 - x**2))

compare(tan(acos(x)), sqrt(1 - x**2)/x)

compare(tan(acot(x)), 1/x)

x = 1/np.random.random()

compare(sin(asec(x)), sqrt(x**2 - 1)/x)

compare(cos(acsc(x)), sqrt(x**2 - 1)/x)

compare(sin(acsc(x)), 1/x)

compare(cos(asec(x)), 1/x)

compare(tan(acsc(x)), 1/sqrt(x**2 - 1))

compare(tan(asec(x)), sqrt(x**2 - 1))

This verifies the first three rows; the last three rows are reciprocals of the first three rows.

[1] G. A. Baker. Multiplication Tables for Trigonometric Operators. The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 64, No. 7 (Aug. – Sep., 1957), pp. 502–503.

[2] These geometric proofs only prove identities for real-valued inputs and outputs and only over limited ranges, and yet they can be bootstrapped to prove much more. If two holomorphic functions are equal on a set of points with a limit point, such as a interval of the real line, then they are equal over their entire domains. So the geometrically proven identities extend to the complex plane.

The post Trig composition table first appeared on John D. Cook.2026-03-09 02:09:48

A couple weeks ago I wrote a post on a composition table, analogous to a multiplication table, for trig functions and inverse trig functions.

My initial version of the table above had some errors that have been corrected. When I wrote a followup post on the hyperbolic counterparts of these functions I was more careful. I wrote a little Python code to verify the identities at a few points.

Of course checking an identity at a few points is not a proof. On the other hand, if you know the general form of the answer is right, then checking a few points is remarkably powerful. All the expressions above are simple combinations of a handful of functions: squaring, taking square roots, adding or subtracting 1, and taking ratios. What are the chances that a couple such combinations agree at a few points but are not identical? Very small; zero if you formalize the problem correctly. More on that in the next post.

In the case of polynomials, checking a few points may be sufficient. If two polynomials in one variable agree at enough points, they agree everywhere. This can be applied when it’s not immediately obvious that identity involves polynomials, such as proving theorems about binomial coefficients.

The Schwartz-Zippel lemma is a more sophisticated version of this idea that is used in zero knowledge proofs (ZKP). Statements to be proved are formulated as multivariate polynomials over finite fields. The Schwartz-Zippel lemma quantifies the probability that the polynomials could be equal at a few random points but not be equal everywhere. You can prove that a statement is correct with high probability by only checking a small number of points.

The first post mentioned above included geometric proofs of the identities, but also had typos in the table. This is an important point: formally verified systems can and do contain bugs because there is inevitably some gap between what it formally verified and what is not. I could have formally verified the identities represented in the table, say using Lean, but introduced errors when I manually transcribe the results into LaTeX to make the diagram.

It’s naive to say “Well then don’t leave anything out. Formally verify everything.” It’s not possible to verify “everything.” And things that could in principle be verified may require too much effort to do so.

There are always parts of a system that are not formally verified, and these parts are where you need to look first for errors. If I had formally verified my identities in Lean, it would be more likely that I made a transcription error in typing LaTeX than that the Lean software had a bug that allowed a false statement to slip through.

The appropriate degree of testing or formal verification depends on the context. In the case of the two blog posts above, I didn’t do enough testing for the first but did do enough for the second: checking identities at a few random points was the right level of effort. Software that controls a pacemaker or a nuclear power plant requires a higher degree of confidence than a blog post.

Suppose you want to rigorously prove the identities in the tables above. You first have to specify your domains. Are the values of x real numbers or complex numbers? Extending to the complex numbers doesn’t make things harder; it might make them easier by making some problems more explicit.

The circular and hyperbolic functions are easy to define for all complex numbers, but the inverse functions, including the square root function, require more care. It’s more work than you might expect, but you can find an outline of a full development here. Once you have all the functions carefully defined, the identities can be verified by hand or by a CAS such as Mathematica. Or even better, by both.