2025-12-31 10:46:44

Published on December 31, 2025 2:11 AM GMT

2026 presents unfathomable opportunities for taking positive action to help the future go well. I see very few people oriented to what I see as many of the foundational basics.

1) With GPT-5.2-Codex-xhigh, Claude Code Opus 4.5, GPT-5.2-Pro, and the increasing DX tooling being created every hour, building wildly ambitious software in absurd time is exceptionally feasible. I am talking 1-6 devs building software platforms in weeks for agent-economies factorizing cognitive work at scale, with ultra-parsimous, easy-to-build-upon Rust codebases. A 2024-cracked-SWE-year's worth of work per day is basically possible already for thousands of people, if they can manage to be healthy enough and find flow.

2) Causing great outcomes basically has to be an additive, personal, bits-on-the-ground thing. You have to find yourself giving brilliant people influence over huge agent swarms, that can just deeply research, understand, and counter certain problem domains, like prion terrorism risk or whatever (because a significant fraction of people crash out sometimes). Real world collective superintelligence, this year, and you are a key part of it.

Trying to get real human builders to be all that oriented to downside risks, or jockeying for unprecedented government lockdown of compute--does not seem to be nearly as existentially practical as just building with good primitives and conscientiously stewarding emergence.

3) The real game is actually more somatics than anything. That doesn't mean full hippie kumbaya all the time, but you probably really do need to move a lot throughout the day, get Bryan Johnson-level sleep, distance from people you really contract around, get some hugs or self-hugs at least, and be gentle with your parts, like your socially-penalized instincts.

Backpropagating from things like millions of healthily-trained agents naturally coordinating cognitive work at scale with simple primitives--pairwise ratio comparisons eliciting cardinal latent scores for arbitrary attribute_prompts over arbitrary entities cached in agent-explorable SQL; multi-objective rerankers; market-pricing; frameworks that agents love for prior elicitation, reconciliation, and propagation--

it's about sitting in front of a laptop and prompting well, a lot. And to do that well, you've got to build up uncommonly good taste for what body signals are safe to ignore and what should really be respected. For me, estrogen (and some exogenous T) and a period of shrooms was absolutely necessary to downregulate, unclench, feel enough, and unlearn unhelpful reactivity patterns, to end up regulated enough to have a minimum viable amount of agency--I was simply too cripplingly heady and stuck before).

The world is a trippy, wildly complicated place as a self-modifying embodied organism, and I think that's to be embraced. The first person-perspective and unflattening of experience is a very real part of the game.

4) Overall, there's a resource flywheel game. Gotta find yourself with more and more dakka. I need more felt-safety, more nutrients, more stewarding of psychic gradients so good prompting and creativity keeps happening more, and I manage to bootstrap my limited $600/month AI compute + Hetzner server budget into $20,000/month into possibly $1M+ a day, by the time agents and harnesses get that good in 2026, to keep doing research and spawning side businesses that solve real problems in the ecology.

2025-12-31 09:31:00

Published on December 31, 2025 1:31 AM GMT

This post presents a brief progress update on the research I am doing as a part of the renormalization research group at Principles of Intelligence (PIBBSS). The code to generate synthetic datasets based on the percolation data model is available in this repository. It employs a newly developed algorithm to construct a dataset in a way that explicitly and iteratively reveals its innate hierarchical structure. Increasing the number of data points corresponds to representing the same dataset at a more fine-grained level of abstraction.

Ambitious mechanistic interpretability requires understanding the structure that neural networks uncover from data. A quantitative theoretical model of natural data's organizing structure would be of great value for AI safety. In particular, it would allow researchers to build interpretability tools that decompose neural networks along their natural scales of abstraction, and to create principled synthetic datasets to validate and improve those tools.

A useful data structure model should reproduce natural data's empirical properties:

To this end, I'm investigating a data model based on high-dimensional percolation theory that describes statistically self-similar, sparse, and power-law-distributed data distributional structure. I originally developed this model to better understand neural scaling laws. In my current project, I'm creating concrete synthetic datasets based on the percolation model. Because these datasets have associated ground-truth latent features, I will explore the extent to which they can provide a testbed for developing improved interpretability tools. By applying the percolation model to interpretability, I also hope to test its predictive power, for example, by investigating whether similar failure modes (e.g. feature splitting) occur across synthetic and natural data distributions.

The motivation behind this research is to develop a simple, analytically tractable model of multiscale data structure that to the extent possible usefully predicts the structure of concepts learned by optimal AI systems. From the viewpoint of theoretical AI alignment, this research direction complements approaches that aim to develop a theory of concepts.

The branch of physics concerned with analyzing the properties of clusters of randomly occupied units on a lattice is called percolation theory (Stauffer & Aharony, 1994). In this framework, sites (or bonds) are occupied independently at random with probability , and connected sites form clusters. While direct numerical simulation of percolation on a high-dimensional lattice is intractable due to the curse of dimensionality, the high-dimensional problem is exactly solvable analytically. Clusters are vanishingly unlikely to have loops (in high dimensions, a random path doesn't self-intersect), and the problem can be approximated by modeling the lattice as an infinite tree[1]. In particular, percolation clusters on a high-dimensional lattice (at or above the upper critical dimension ) that are at or near criticality can be accurately modeled using the Bethe lattice, an infinite treelike graph in which each node has identical degree . For site or bond percolation on the Bethe lattice, the percolation threshold is . Using the Bethe lattice as an approximate model of a hypercubic lattice of dimension gives and . A brief self-contained review based on standard references can be found in Brill (2025, App. A).

The repository implements an algorithm to simulate a data distribution modeled as a critical percolation cluster distribution on a large high-dimensional lattice, using an explicitly hierarchical approach. The algorithm consists of two stages. First, in the generation stage, a set of percolation clusters is generated iteratively. Each iteration represents a single "fine-graining" step in which a single data point (site) is decomposed into two related data points. The generation stage produces a set of undirected, treelike graphs representing the clusters, and a forest of binary latent features that denote each point's membership in a cluster or subcluster. Each point has an associated value that is a function of its latent subcluster membership features. Second, in the embedding stage, the graphs are embedded into a vector space following a branching random walk.

In the generation stage, each iteration follows one of two alternatives. With probability create_prob, a new cluster with one point is created. Otherwise, an existing point is selected at random and removed, becoming a latent feature. This parent is replaced by two new child points connected to each other by a new edge. Call these points a and b. The child points a and b are assigned values as a stochastic function of the parent's value. Each former neighbor of the parent is then connected to either a with probability split_prob, or to b with probability 1 - split_prob. The parameter values that yield the correct cluster structure can be shown to be create_prob = 1/3 and split_prob = 0.2096414. The derivations of these values and full details on the algorithm will be presented in a forthcoming publication.

In the coming months, I hope to share more details on this work as I scale up the synthetic datasets, train neural networks on the data, and interpret those networks. The data model intrinsically defines scales of reconstruction quality corresponding to learning more clusters and interpolating them at higher resolution. Because of this, I'm particularly excited about the potential to develop interpretability metrics for these datasets that trade off the breadth and depth of recovered concepts in a principled way.

Percolation on a tree can be thought of as the mean-field approximation for percolation on a lattice, neglecting the possibility of closed loops.

2025-12-31 08:45:09

Published on December 31, 2025 12:45 AM GMT

In 2025, AI models learned to effectively search and process vast amounts of information to take actions. This has shown its colors the most in coding, eg through harnesses like claude code that have had a sizable impact on programmers’ workflows.

But this year of progress doesn’t seem to have had that much of an effect on the personalization of our interactions with models, ie whether models understand the user’s context, what they care about, and their intentions, in a way that allows them to answer better. Most chatbot users’ personalization is still limited to a system prompt. Memory features don’t seem that effective at actually learning things about the user.

But the reason machine learning has not succeeded at personalization is lack of data (as it often is!). We do not have any validated ways of grading ML methods (training or outer-loop) for personalization. Getting good eval signals for personalization is hard, because grading a model’s personalization is intrinsically subjective, and requires feedback at the level of the life and interactions that the model is being personalized to. There is no verified signal, and building a generic rubric seems hard. These facts do not mesh well with the current direction of machine learning, which is just now starting to go beyond verifiable rewards into rubrics, and is fueled by narratives of human replacement that make personalization not key (If I am building the recursively improving autonomous agi, why do I need to make it personalized).1

But how do we obtain data for personalization? I think the first step to answering this question is having consumers of AI curate their personal data and then share it to enrich their interactions with AI systems.

Instead of just a system prompt, giving models a searchable artifact of our writing, notes, and reading history. Something agents can explore when your questions might benefit from context—and write to, to remember things for later.

Over the break, I built a very simple software tool to do this. It’s called whorl, and you can install it here.

whorl is a local server that holds any text you give it—journal entries, website posts, documents, reading notes, etc…—and exposes an MCP that lets models search and query it. Point it at a folder or upload files.

I gave it my journals, website, and miscellaneous docs, and started using Claude Code with the whorl MCP. Its responses were much more personalized to my actual context and experiences.

First I asked it:

do a deep investigation of this personal knowledge base, and make a text representation of the user. this is a text that another model could be prompted with, and would lead them to interacting with the user in a way the user would enjoy more

It ran a bunch of bash and search calls, thought for a bit, and then made a detailed profile of me, and my guess is that its quality beats many low effort system prompts, linked here.

I’m an ML researcher, so I then asked it to recommend papers and explain the motivation for various recs. Many of these I’ve already read, but it has some interesting suggestions, quite above my usual experience with these kinds of prompts. See here.

These prompts are those where the effect of personalization is most clear, but this is also useful in general chat convos, allowing the model to query and search for details that might be relevant.

It can also use the MCP to modify and correct the artifact provided it, to optimize for later interactions – especially if you host a “user guide” there like the one I linked. Intentionally sharing personal data artifacts is the first step to having agents that understand you.

Personalization requires data. People need to invest into seeing what models can do with their current data, and figuring out what flows and kinds of interactions this data is useful for, towards building technology that can empower humans towards their goals. whorl is a simple tool that makes that first step easy. People who have already created a bunch of content should use that content to enhance their interactions with AIs.

2025-12-31 08:36:10

Published on December 31, 2025 12:36 AM GMT

Please remember how strange this all is.

I am sitting in an airport in San Francisco. It is October 2025. I will get in a box today. It will take my body around the world in unbreathable air at 600mph.

The machines I see outside the departure lounge window are complicated and odd. Millions of computer chips and wires and precisely designed metal structures. Gears and belts and buttons. No individual knows how these things work.

I look down at my body. Even more unimaginably complex. An intricate soup of skin, DNA, fat and protein. Enzyme cascades and neuronal developmental pathways. These cascades are collectively producing these words somehow.

Please remember how strange this all is.

All this stuff exists, but we don’t know why. I am seeing and feeling and thinking about all this stuff and we don’t know why any of it is here. Nobody does. We make plans, we gossip, we deliver projects and look forward to holidays. We social climb and have sex and hold hands. We go swimming on a Saturday morning with a close friend and talk about our relationships and the water temperature and we silently agree to forget how deeply strange it is that any of this is even here and is like it is.

Please remember how strange this all is.

Experience is so absurdly specific. So surprisingly detailed. I am lost in my story; in the excruciatingly specific normality of it. Occasionally I remember. An obvious contrast. A strong memory. A flash of confusion. I sometimes remember, but I mostly forget. Remembering usually feels like a distraction from the thing that is happening now. It often is. I ask that you remember anyway.

Please remember how strange this all is.

Is this cliché? Am I being cliché? Or is that feeling of cliché-ness just more forgetting? More “this is normal”, more “this is usual and expected”.

We walk past each other on the street and forget the absurd mystery of why any of this is here. The strangeness and lostness in stories is the most reliable feature of all of our reality. Our confusion is the core vulnerability that we all share. Join me in the one place we can all meet.

Please remember how strange this all is.

The music playing in my ears. The movement of my pen on this paper. The feeling that these words are me. The flash of a vivid memory from last night. The complex web of social plans. The implicit meta-physics my thoughts are nestled within.

Please remember how strange this all is.

The woman behind the counter at the departure lounge café. The sound of boarding announcements. The complex array of brands of drink. Colourful and alluring and strange. The artwork in front of me is paper boats in water.

Please remember how strange this all is.

I talked to an old friend this morning in an Italian restaurant in The Embarcadero. He’s worried about AI and is dreaming of buying a house in the countryside. He wants to move away from the bay and stop fighting for the future of humanity.

Please remember how strange this all is.

Also remember to breathe. Breathe deep. Breathe deep through your nose and into your belly. Remember the centre. Remember to feel into your heart. Touch grass with your feet. Notice the consistent patterns and trust the context of your own perception. Seriously, remember to be breathe.

Then let go of that too. And remember again how deeply strange this all is.

2025-12-31 05:55:05

Published on December 30, 2025 9:55 PM GMT

Reposting my Inkhaven post on ontology of advice here.

Are you interested in learning a new field, whether it’s programming, writing, or how to win Paper Mario games? Have you searched for lots of advice and couldn’t choose which advice to follow? Worse, have you tried to follow other people’s Wise Sounding Advice and ended up worse than where you started?

Alternatively, have you tried to give useful advice distilling your hard-earning learnings and only to realize it fell on deaf ears? Or perhaps you’ve given advice that filled a much-needed hole that you now regret giving?

If so, this post is for you!

While this post is far from exhaustive, I hope reading it can help you a) identify the type of advice you want to give and receive and b) recognize and try to avoid common failure modes!

Source: https://englishlive.ef.com/en/blog/english-in-the-real-world/5-simple-ways-give-advice-english/

Here are 7 semi-distinct categories of good advice. Some good advice mixes and matches between the categories, whereas others are more “purist” and just tries to do one style well.

This is where someone who deeply understands a field tries to impart the central tenets/frames of a field so newbies can decide whether the model is a good fit for what they want to do. And the rest of the article/book/lecture will be a combination of explaining the model and why they believe it’s true, and examples to get the learner to deeply understand the model. Eg “Focus on the user” as the central dictum in tech startups, or understanding and groking the Popperian framework for science.2

My previous post, How to Win New Board Games, is an unusually pure example, where I spend 2000 words hammering different variations and instantiations of a single idea (“Understand the win condition, and play to win”).

In writing advice, Clear and Simple as the Truth (by Thomas and Turner, review + extension here) works in this way as well, doing their best to model how to write well in the Classic Style.

“When art critics get together, they talk about form and structure and meaning. When artists get together, they talk about where you can buy cheap turpentine.” - Pablo Picasso, supposedly3

The motivating theology is something like “reality has a surprising amount of detail“, and you want to impart these details onto novices. In tech startups, this could be a list of 20 tips. In videogames, this could be a youtube video that goes through a bunch of different tips.

My first post this month, How to Write Fast, Weird, and Well, is mostly in this vein, with a collection of loosely structured tips that I personally have found to be the most helpful in improving myself as an online writer.

Teaching through stories and examples rather than principles or tips. Business schools love this approach (case studies), as do many mentors who say “let me tell you about the time I...” The idea is that patterns emerge from concrete situations better than from abstract rules. While not stereotypically considered an “advice book,” the nonfiction book I’m currently the most engrossed in, Skunk Works, is written almost entirely as a collection of war stories.

For games, this could be videos of professional streams. In writing, this would be books like Stephen King’s “On Writing”, which weaves memoir with advice.

Can you think of good questions to guide your students, rather than declarative statements?

The minimal viable product for this type of advice is just being a “pure” mirror. Have you tried just asking your advisee what they’re thinking of doing and what they think the biggest flaws with their plans are? Otherwise known as “Socratic ducking,” this is where your questions essentially just mirror your advisee’s thoughts and you don’t try to interject any of your own opinions or tastes in the manner. Surprisingly useful!

In more advanced “mirror strategies,” the advisor’s questions might serve more as prisms, lenses, or funhouse mirrors. Can you do better than a pure mirror? Can you think of some common failure modes in your field and ask your advisees pointed questions so they can address those? Can you reflect your subtle judgments in taste and prioritization and reframe your tips into central questions of interest?

Coaching and therapy often works this way. Instead of “focus on the user,” it’s “who do you think will use this and what do they need?”

There’s a spectrum of mirror purity vs detail. In the most detailed end, maybe you should just give your normal advice but say it with an upwards inflection so it sounds like a question?

This is advice like “be yourself” or “chase your dreams.” This might initially seem to be semantically useless, but there’s real value in giving license for people to do (socially positive) things they kind of want to do anyway. In Effective Altruism, this could be something like “when in doubt, just apply (to socially positive jobs)” or “you don’t need permission to do the right thing.”

In writing advice, this could be seemingly trivial advice like telling aspiring writers to just start writing, or telling writers worried about style that your style ought to be an expression of your personality.

Advice that helps you figure out what specific bottleneck is, or the specific thing (among a suite of options) that would help you the most. Some product reviews might look like this.

The post you’re reading right now is also somewhat in this vein! Hopefully after reading the post, you’d have a better sense of what types of advice you’d find most useful to give or receive.

Advice for what not to do, scary things newbies should avoid, etc. In most fields, learning the Landmines is supplementary advice. But in certain high-stakes domains where beginners have enough agency to seriously hurt themselves or others like firearms practice, outdoor climbing, or lab chemistry, it’s the prerequisite advice.

Of course, many advice posts/essays/books might integrate two or more of the above categories. For example, my Field Guide to Writing Styles post mixes a meta-framework (master Master Key) for choosing which framework/frameworks to write in (Diagnostic), with specific frameworks/writing styles you might want to write in. While in some sense this is more sophisticated and interesting to write (and hopefully to read!) than advice in a single “pure” category, it also likely suffers from being more scattered and confusing. So there are real tradeoffs.

Is the above ontology complete? What am I missing? Tell me in the comments!4

There are an endless plethora of ways advice can be bad, and fail to deliver value to the intended audience (eg the advice is ignored), or deliver anti-value to the intended audience (the advice is taken, and taking the advice is worse than not taking it).

In this article, I will just focus on the biggest ones.

The biggest three reasons are that the advisor can fail at metacognition, the advice can fail to center the advisee, or the advice can otherwise fail to be persuasive

The advisor can fail at metacognition, and do not know the limits of their knowledge

Many of these failure modes can be alleviated through clearer thinking and better rationality.

The advice can fail to center the advisee.

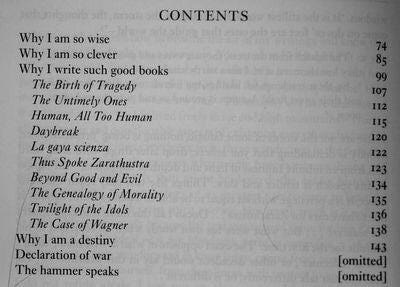

Nietzsche’s great at self-promotion, but not the best at meta-cognition or audience awareness.

The advice can be in the wrong category for the audience of interest

Many of these failure modes can be alleviated through greater empathy and revealed desire to help others.

This category is somewhat less bad than the previous two categories, as the damage is limited.

Many of these failure modes can be alleviated by improvements in writing quality in general. They can also be reduced via learning about other (ethical/semi-ethical) forms of self-promotion, which I have not yet cracked but hope to do so one day (and will gladly share on the blog).

What do you think? Are there specific categories of advice you're particularly drawn to? Are there (good) categories of advice that I missed? Tell us in the comments!

I realize this is a bit of a trap/local optima to be stuck in, so starting tomorrow, I’m calling for a personal moratorium on publishing advice posts until at least the end of this week!

Sometimes the central tenet can be explained “well enough” in one sentence, like “focus on the user.” Often, it cannot be.

Apocryphal

(For simplicity I’m ignoring high-context/specific/very situational advice, like specific suggested edits on a blog post, or an experienced programmer providing code review). I’m also excluding exercise “books” like Leetcode or writing prompts.

I was a decent but not great (by Silicon Valley standards) programmer, so it’s possible there is a central dogma I was not aware of. But I also read dozens of books at programming and worked at Google for almost 2 years, so at the very least the memescape did not try very hard to impress upon me a central dogma

2025-12-31 03:50:26

Published on December 30, 2025 7:50 PM GMT

When you sell stock [1] you pay capital gains tax, but there's no tax if you donate the stock directly. Under a bunch of assumptions, someone donating $10k could likely increase their donations by ~$1k by donating stock. This applies to all 501(c) organizations, such as regular 501(c)3 non-profits, but also 501(c)4s such as advocacy groups.

In the US, when something becomes more valuable and you sell it you need to pay tax proportional to the gains. [2] This gets complicated based on how much other income you have (which determines your tax bracket for marginal income), how long you've held it (which determines whether this is long-term vs short-term capital gains), and where you live (many states and some municipalities add additional tax). Some example cases:

A single person in Boston with other income of $100k who had $10k in long-term capital gains would pay $2,000 (20%). This is 15% in federal tax and 5% in MA tax.

A couple in SF with other income of $200k who had $10k in long-term capital gains would pay $2,810 (28%). This is 15% in federal tax, 3.8% for the NIIT surcharge, and 9.3% in CA taxes.

A single person in NYC with other income of $600k who had $10k in short-term capital gains would pay $4,953 (50%). This is 35% in federal tax, 3.8% for the NIIT surcharge, 6.9% in NY taxes, and 3.9% in NYC taxes.

When you donate stock to a 501(c), however, you don't pay this tax. This lets you potentially donate a lot more!

Some things to pay attention to:

Donations to political campaigns are treated as if you sold the stock and donated the money.

If you've held the stock over a year and are donating to a 501(c)3 (or a few other less common ones like a 501(c)13 or a 501(c)19) then you can take a tax deduction of the full fair market value of the stock. This is bizarre to me (why can you deduct as if you had sold it and donated the money, when if you had gone that route you'd have needed to pay tax on the gains) but since it exists it's great to take advantage of.

This only applies if it's a real donation. If you're getting a benefit (ex: "donating" to a 501(c)3 but getting a ticket to an event) that's not a real gift and doesn't fully count.

If you're giving to a person, you don't pay capital gains, but they get your cost basis (with some caveats). When they sell they'll pay capital gains tax, which might be more or less than you would have paid depending on your relative financial situations. If they're likely to want to make a gift to charity, though, it's much more efficient to give them the stock.

The actual logistics of donating stock are a pain. If you're giving to a 501(c)3 it's generally going to be logistically easier to transfer the stock to a donor-advised fund (I use Vanguard Charitable because it integrates well with Vanguard), which can then make grants to the charity. This also has a bonus of letting you pick the charity later if you want to squeeze this in for 2025 but haven't made up your mind yet.

[1] I say "stock" throughout, but this applies to almost any kind of

asset.

[2] Note that "gains" here aren't just the real gains from your stock becoming more valuable, but also include inflation. For example, if you bought $10k in stock five years ago ($12.5k in 2025 dollars) and sold it today for $12.5k in 2025 dollars, you'd have "gains" of $2,500 even though all that's actually happened is that the 2025 dollars you received are less valuable than 2020 dollars you spent.