2025-12-17 06:44:00

People often ask me where I get ideas for this Substack. The simple answer is everywhere, even a Christmas tree lot on a cold night in December.

When my brother and I were kids, each year we would make the annual trip with our dad to pick out the family Christmas tree. But when we left for college, he was left to make the selection without us. That is until recently when we decided the old man needed some help.

Now, one might conclude that we did so because at 78 and a shade under 5’4, wrestling a nine-foot tree off the car roof had become a nearly-impossible task. While true, our rationale ran deeper — we thought he needed “air cover.”

Air cover?

Yes, air cover.

In short, we needed to witness his selection process so that we could defend him.

See, in what had become a Christmas ritual in the Lamade house, every year for as long as I can remember, my dad would go out, buy a tree, put it up on the stand, and my mom would immediately spot the flaws. Hole on one side. Dead patch in the middle. Leaning hard to the left. An obvious flat top. You name it, we’ve had it.

For years my brother and I would go into full blown “PR mode” after the tree went up, saying things like:

“The tree will look nice once it drops.”

“Dad did his best.”

“It’s Christmas — give him a break.”

But candidly, we kept asking ourselves the same question, how does this keep happening?!?!

I mean, my mom wasn’t wrong. These trees nearly always had something wrong with them.

That is, until my brother and I finally saw him in action on the lot last year. Like the Hardy Boys, we solved our childhood mystery almost instantaneously.

When we arrived at the lot, the two of us prepared to fan out to look for a tree. The goal was simple – find a nine-footer with no dead branches, not too big…not too small, and certainly no flat tops.

Then it happened. Something the two of us had not prepared for. It was akin to the moment as a kid when you find out the whole secret behind Santa.

So, what was it?

Practically the minute we walked onto the lot, my dad pointed to the first nine-footer he saw and said – “We’ll take that one.” Huh? Was this a joke??

Then it all made sense. This is how he had managed to bring home an imperfect tree year-after-year. He didn’t search. He didn’t compare. He didn’t think about how a tree would look after it “dropped.” He simply saw one that looked good enough and bought it. Witnessing what had just happened, the two of us turned to him and said,

“What are you doing? You cannot be serious!?!?”

He then looked at us like we were the crazy ones and said,

“What do you mean ‘am I serious’? Of course I am serious. Your mother will find something wrong with any tree I bring home, so why spend an hour in the freezing cold looking for one?”

Here’s the thing. He wasn’t wrong. But there was more to it.

My dad has always been drawn to the oddball. The misfit. The underdog. The one with “character.” Deep down, I think he liked “rescuing” the ugly tree from the lot. I even think he got a kick out of imagining the moment Mom would see it and deliver the annual critique. The whole thing amused him.

And truthfully, we have laughed about our trees every year. The one with the massive hole. Ole Flat Top. The one that looked like it had fallen over six times. Best yet, after critiquing them initially, almost every year my mom eventually comes around to liking these trees.

Which leads me to the real point.

People think Christmas is about perfection – the perfect house, the perfect photo, the perfect gifts, the perfect everything. But the moments we actually remember aren’t the flawless ones.

We remember the misfit tree.

We remember freezing with our dad in the Christmas tree lot, the uncle who had a few too many adult beverages, and the overly dry turkey.

We also remember the cousin who was allergic to the family dog and almost fell asleep at dinner after taking too much Benadryl (me) and the older brother who shot his younger brother in the rear-end from three feet away with a paintball gun he got for Christmas (also me…the shooter that is.)

Yet, somewhere along the way, we lost sight of this. Perfection, or the perception of it, has become the goal. We curate our lives on YouTube through highlight reels and post our airbrushed photos from vacation on Instagram. It’s why people are increasingly using artificial intelligence to “perfect” nearly everything they do. And yes, it’s why people are increasingly buying artificial Christmas trees….because they are easier to set up, cleaner to maintain, and “perfect” in so many ways.

But here’s the question:

By attempting to remove all the imperfections in life, are we removing the stories? The moments that make us laugh? The mistakes and imperfections that make us uniquely human?

I don’t know. Maybe I sound like the Grinch. Maybe I am overly nostalgic for the past. Maybe I just need to accept that this is what progress looks like. Or maybe, just maybe, there is something special about the tree with the flat top. The one that leans a little. The one with “character.” The one you talk about for weeks, if not years later. The one that reminds you that since perfection is impossible, you might be better off simply embracing life’s imperfections.

UPDATE:

After I finished writing this, I had a work conference in Georgia. As a result, I unfortunately had to miss the annual tree decorating night at my parent’s house, which is a highlight of the Christmas season for all of us, especially the grandkids.

This year, since it was on the same day as my flight, I called my wife when I landed to see how it was going. Her response?

“Ted, you won’t believe it. The tree fell over.”

My reaction?

Now that’s perfect, in every sense of the word.

2025-12-01 05:44:00

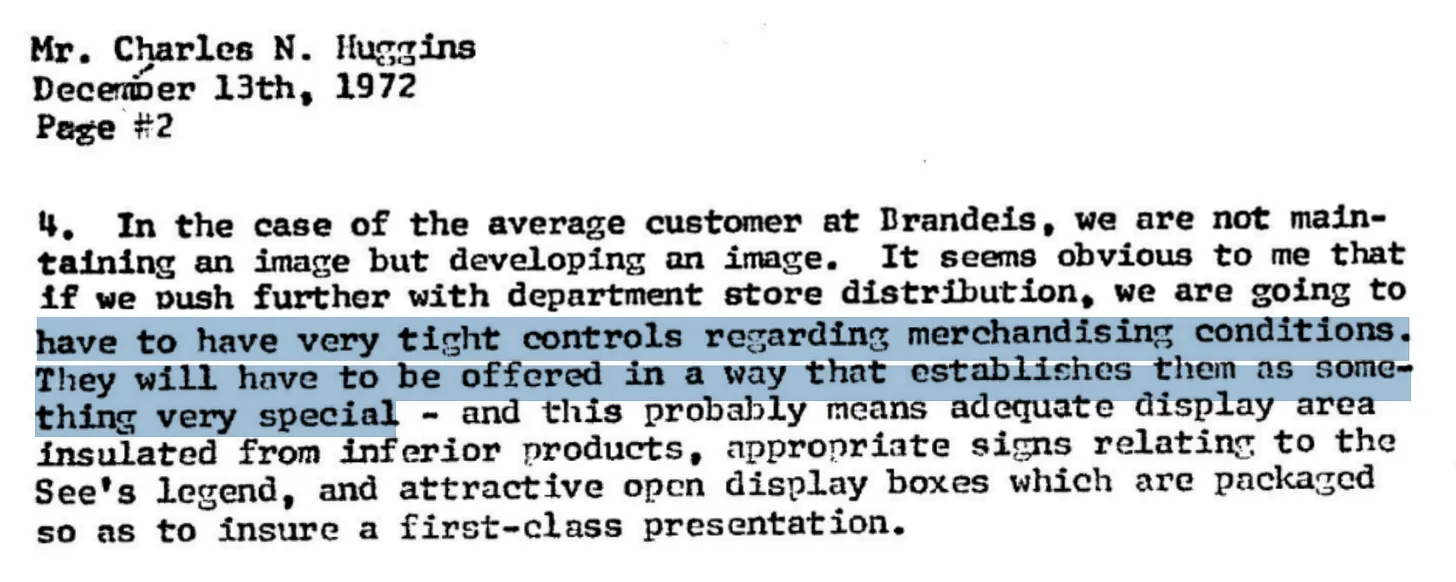

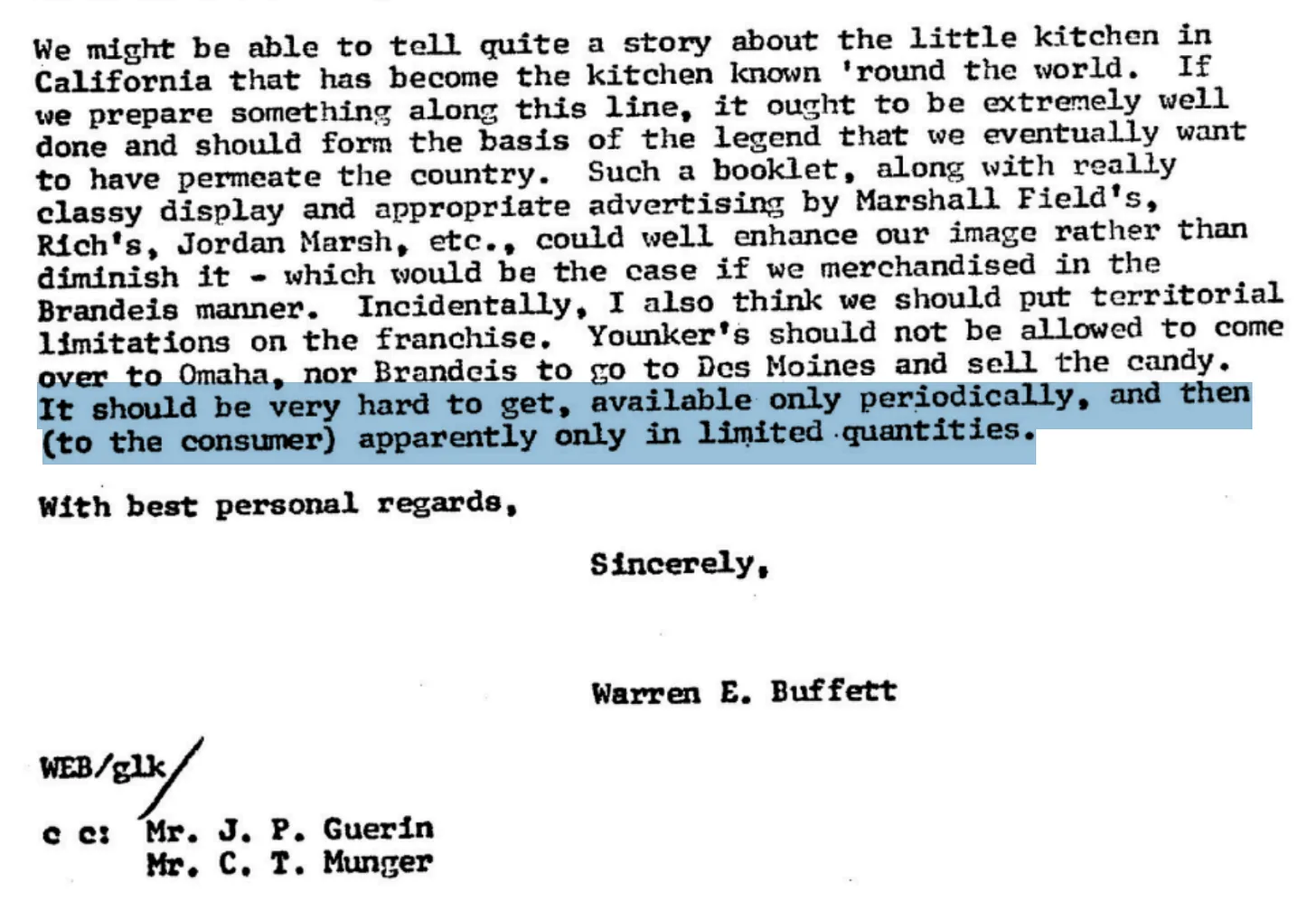

A few weeks ago, I came across a letter Warren Buffett wrote in 1972 to Chuck Huggins, then president of See’s Candy. It’s two pages long, typed on letterhead, and quietly brilliant.

Reading it now, more than fifty years later, it feels less like an internal memo and more like a manifesto about what makes a brand endure.

“People are going to be affected not only by how our candy tastes,” Buffett wrote, “but by what they hear about it from others as well as the retailing environment in which it appears.”

In those lines, you can see how Buffett was already thinking far beyond unit economics or margins. He understood that the true value of See’s wasn’t measured by its ingredients or its quarterly earnings. It was in the feeling the brand produced - the trust, nostalgia, and quiet pride that came with handing someone a white and gold box tied in ribbon.

He was describing brand equity before that term was widely used.

Buffett often talks about moats; the durable competitive advantages that protect a company over decades. In See’s Candy, he found one that was remarkably intangible: customer love.

It’s easy to think of Buffett as the world’s most disciplined value investor. But letters like this reveal something deeper. He has always been a brand investor, someone who recognizes that the strongest companies don’t just sell products; they sell belief. They create environments and stories that compound over time.

“If we push further with department store distribution,” he cautioned, “we are going to have to have very tight controls regarding merchandising conditions. They will have to be offered in a way that establishes them as something very special.”

He knew that brand perception couldn’t be outsourced. Every display, every piece of packaging, every interaction mattered. That resonates deeply with how we try to invest at Collaborative Fund. The moat we care most about is emotional, not transactional.

We often say that great brands “scratch an itch” — they solve a deep, recurring need that people actually feel. In 2013, I wrote a short post by that name, arguing that the best companies are the ones that clearly answer two questions:

Buffett, a decade before many modern brand marketers were born, intuited this perfectly. He knew that See’s scratched a very specific societal itch — not hunger, but something closer to affection: the ritual of gifting, the small gesture that says I thought of you.

That’s the kind of intangible value that compounds quietly for decades. You can’t model it in Excel, and you won’t find it in a discounted cash flow. But you can feel it in the way people talk about the brand, and the way they keep returning to it year after year.

Buffett has always described his preferred business as one that “can raise prices without losing customers.” What he really means is one that has earned the right to be loved and trusted.

See’s Candy could do that because it felt rare, careful, and human. Everything around it reinforced that perception. Buffett even wrote that it “should be very hard to get, available only periodically, and then apparently only in limited quantities.”

He was thinking like a cultural anthropologist, not just an investor. He understood the psychology of desire.

That’s what we look for at Collab — companies with purpose and empathy baked into their DNA, where the brand’s story and product experience are inseparable. Companies that, like See’s, pass what we call the Villain Test: if they disappeared tomorrow, who would be genuinely sad?

Buffett bought See’s for $25 million. Since then, it has produced billions in profit for Berkshire Hathaway and an immeasurable amount of goodwill for customers who still associate those signature boxes with care, quality, and connection.

Half a century later, the letter reads like an early draft of the Collaborative investment philosophy. He wasn’t talking about candy at all, really. He was talking about trust, consistency, delight — all those overlooked forces that turn a product into a brand and a brand into a legend.

That’s still the itch we’re trying to scratch.

2025-11-05 01:44:00

Like millions of others, I’ve been watching and playing with OpenAI’s new video model, Sora—and I keep thinking about how often technology outpaces permission. One week it’s coffee apps; the next, it’s cinematic worlds spun from text. Each innovation starts as convenience and ends up rewriting the rules.

Starbucks didn’t mean to become a financial institution. But every era of innovation finds its own way to test the rules.

The world runs on rules. But rules run on paperwork, committees, and calendars. Technology, on the other hand, runs on curiosity and caffeine.

That mismatch—between how fast people can build and how slowly institutions can respond—has become one of the defining forces of modern life. It’s not that people are breaking the law; it’s that the law no longer describes what people are doing.

Starbucks is a coffee company. But in financial terms, it’s also one of the largest banks in America. Customers collectively hold nearly $2 billion in prepaid balances on Starbucks cards and apps—more than 85 percent of U.S. banks hold in total deposits.

The twist is that customers didn’t entirely choose this setup. When you pay with the Starbucks app, you can’t simply use your credit card in the moment. You have to preload money into an account. That single design choice—subtle, convenient, and completely intentional—turned every latte purchase into a micro-deposit. Starbucks quietly became a financial institution without ever applying for a banking license.

This is how change usually happens in technology: not through rebellion, but through design. What begins as a product feature becomes a regulatory blind spot, and over time, an accepted norm.

If Starbucks represents the subtle version of this phenomenon, Uber is its loud, brash archetype.

Uber wrote the modern playbook for testing the limits of regulation. Launch first, operate in the gray, and let adoption create legitimacy. By the time regulators react, public opinion—and billions in rider demand—make reversal almost impossible.

Uber’s true innovation wasn’t just the app itself. It was the recognition that once technology hits a certain scale, the question shifts from “Is this allowed?” to “How do we live with it?” That approach—move fast, find the edges, let the system adapt—has become the default operating system of the modern tech economy. Starbucks, in its own quiet way, followed it. So have crypto networks, prediction markets, and now, artificial intelligence companies.

OpenAI’s new video model, Sora, can generate cinematic footage from a text prompt. It’s astonishing. But behind that wonder lies a familiar discomfort: whose work did it learn from?

The model didn’t invent its sense of movement, light, and storytelling in isolation. It absorbed it—from films, animation, design, and photography created by millions of people who were never asked, credited, or compensated. The company insists this is legal, and perhaps under current law it is. But legality and legitimacy are not the same thing.

Copyright law wasn’t built for an era when a machine could absorb the collective visual memory of humanity. It was written for a world where “copying” meant pressing paper or burning film. The law still speaks the language of ownership. The technology now speaks the language of ingestion.

That gap—between what’s legal and what’s right—is where power quietly accumulates.

For most of history, invention was the bottleneck. Today, interpretation is. Regulators deliberate in years; developers iterate in days. By the time the rules catch up, the loophole has become the market.

We still talk about regulation as if it defines the edges of what’s possible. Increasingly, it just describes what people already decided to do. But acceptance and fairness are not the same thing. Just because something scales doesn’t mean it should.

As formal oversight struggles to keep pace, informal ones have stepped in: reputation, public trust, user backlash. They’re faster than legislation, but also more fragile.

The world needs builders bold enough to test limits, but principled enough to remember why those limits existed in the first place. Progress that erases the people it depends on isn’t progress—it’s extraction.

Every major leap forward begins in a gray area. Railroads, credit cards, the internet—all bent old rules until society decided whether to rewrite them or live with the consequences. Artificial intelligence is just the latest in that lineage.

The challenge isn’t stopping innovation; it’s ensuring that the people writing the future still feel accountable to the ones living in it. The future doesn’t always ask for permission. But maybe it should still ask for consent.

2025-10-08 23:25:00

After winning a Golden Globe in 2006, Phillip Seymour Hoffman replied to a question about how he got to this moment in his life.

Nearly two decades later, his response is more relevant than ever.

“Even if you are auditioning for something you know you don’t like or are never going to get, whenever you get a chance to act in a room that someone else has paid for, it is a free chance to practice your craft. And in that moment, you should act as well as you can because if you leave that room and you have done this, there is no way the people who watched you will forget it. That is the only advice I have because it is always about that — if you are given the chance to act, take those words and bring them alive; and if you do that, something will ultimately transpire.”

This mindset explains how within two years, Hoffman played Sandy Lyle in Along Came Polly and Truman Capote in Capote, winning an Oscar for the latter.

Retired United States Navy General William McRaven echoed a similar sentiment in his book, The Wisdom of the Bullfrog, writing,

“I found in my career that if you take pride in the little jobs, people will think you worthy of the bigger jobs.”

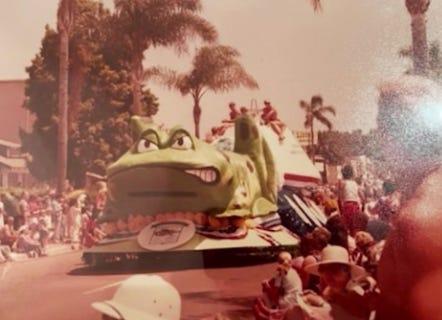

He illustrated this point with a story from early in his career when rather than being assigned to lead a mission, he was tasked with building a float that would represent the Navy SEALs (often referred to as “frogmen”) in the Fourth of July parade.

After receiving the assignment, McRaven was admittedly dejected. In his mind, he had joined the Navy SEALs to lead missions, not build parade floats. But a seasoned team member offered him a quiet piece of advice, saying:

“Sooner or later we all have to do things we do not want to. But if you are going to do it, do it right. Build the best damn Frog Float you can.”

McRaven took the message to heart, pouring himself into the task and the float went on to win first prize in its category.

Over time, McRaven would lead far more consequential missions, including commanding the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) and later the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), which oversees all U.S. special operations forces, including the Navy SEALs, Army Green Berets, and Air Force Pararescue.

Unfortunately, I didn’t appreciate this lesson enough early in my career. As an example, after graduating from business school, I thought I could come right in and impart my newly found wisdom, when I should have been a better listener and executed the mundane tasks with as much vigor as the more interesting ones.

Fortunately, I don’t think I am alone. If I had to guess, anyone reading this can point to a similar moment in their career.

The thing is, this happens to all of us. Even the very best.

Look no further than Tom Brady, who has admitted he was consumed by this mentality early in his career at Michigan.

After his sophomore season, Brady was buried on the depth chart, only getting one or two reps per practice. As a result, he expressed his frustration to the coaches, to which head coach Lloyd Carr responded,

“Brady, I want you to stop worrying about what all the other players on our team are doing. All you do is worry about what the starter is doing, what the second guy is doing, what everyone else is doing. You don’t worry about what you are doing. You came here to be the best. If you’re going to be the best, you have to beat out the best.”

Carr then suggested Brady meet with Greg Harden, a counselor in the athletic department.

Once again, Brady vented his frustration — complaining about getting limited reps.

Harden’s advice was simple:

“Just focus on doing the best you can with those two reps. Make them as perfect as you possibly can. Then focus on the next two, and the next two, and the next two.”

How did Brady respond?

In his words,

“So, that’s what I did. They would put me in for those two reps, and man, I would sprint out there like it was the Super Bowl. I’d shout, ‘Let’s go boys! Here we go! What play we got?!?’ And I started to do really well with those two reps because I brought enthusiasm and energy. Soon, I was getting four reps. Then ten, and before you knew it, with this new mindset that Greg had instilled in me — to focus on what you can control, to focus on what you’re getting, not what anyone else is getting. To treat every rep like it’s the Super Bowl — eventually, I became the starter.”

We all know how Brady’s story played out from here, and it all started with two reps.

Last spring, my then eight-year-old son was wrestling with getting to play very limited minutes, so I read him this story about Brady. After sitting in silence for a few seconds, he looked up at me and said, “Tom Brady barely played too??”

To which I responded, “Yeah bud, like you. You just gotta make the best of your chances you’re given.”

After leaving his room that night, I thought to myself — I would give just about anything to be able to go back in time and tell my younger self this.

Would I have listened?

I hope so, but if this is a hard concept for adults to grasp, I imagine it’s even more difficult for kids.

Nonetheless, I wish I had appreciated this fact of life earlier. The fact is, someone is almost always watching, so it’s worth treating everything you do with purpose and pride. And, even if no one has their eyes on you, it is still a chance to “practice your craft”. To improve. To build strong habits.

Since time is limited, we only get so many opportunities.

We might as well take advantage of each one we get.

2025-09-18 05:52:00

The beginning of a new school year is a unique time in every kid’s life. A time full of expectations, and equal amounts of trepidation and excitement. The same could be said for their parents, which is why I was struck by this list of suggestions that a lower school head wrote for a back-to-school night.

Parents,

A few suggestions for the upcoming school year:

1. Try to remain objective about your child and realistic about your expectations. We are not talking here about loving your child any less — just about viewing his strengths and limitations in a realistic way.

2. Keep yourself well-informed and open to the observations of others about your child. Such people as teachers and coaches can provide you with valuable pieces of information, and you need to take the time to listen.

3. Accept “bad news” as a problem to be dealt with. Do everything you can to keep yourself from overreacting. Keep calm and think! Remember that even we parents have made a mistake or two along the way.

4. Listen carefully to your children, but make the distinction between listening to them and agreeing with them. Kids are good at conveying a perspective. Don’t succumb to the temptation to equate the child’s perspective with “the truth.”

5. Leave the child some unscheduled time. You would be surprised to see the number of kids who can’t seem to do anything unless it’s been planned and scheduled for them. Remember the old days when we had to determine for ourselves some of the things we were going to do with our time.

6. Act consistently over time; and, mothers and fathers, act together. Don’t make empty threats. Don’t let children play off one parent against the other.

Our main goal is to help your child develop into an intelligent, thoughtful, compassionate, contributing adult — a person who years from now is able to say to themselves: “I have the capacity to make sound decisions and to work through obstacles on my own.” The decisions you make along the way can serve either to enhance or reduce the probability that the goal will be reached.

For any parent who read this, it probably resonated. It did for me at least.

Now, what if I let you in on a little secret?

What if I told you this was written in 1992??

I’ll be honest, when I first read it, I was both surprised and relieved. Surprised because it is almost exactly what I would expect a head of school to suggest for parents in 2025. Relieved because it is a reminder that one thing that never changes over time is human behavior.

While this list pertains to how we parent our kids, it could apply to many other things in life — including business and investing.

#1 — Remain objective and realistic about your expectations

Parents have wrestled with this challenge for generations, and likely always will. It’s only natural to want the best for our children, and to want the best from them as well. Yet the truth is, true greatness is the exception, not the rule. However, recognizing that reality feels harder today than ever before.

The reason?

In part because social media’s curated clips of kids scoring goals, acing tests, mastering instruments, and winning awards convince parents that their own kids are lagging. They subsequently pile on more coaching, tutoring, and specialization, which unfortunately has a better chance of breeding burnout than greatness.

Many investors today are suffering from something similar, evidenced by the rise in the popularity of riskier investments like private equity, leveraged ETFs, and crypto, while others are increasingly falling for “get-rich-quick” schemes.

Why?

For the same reasons parents lose their objectiveness. Whether it’s seeing Jeff Bezos on his yacht, the women in The Real Housewives of Name that City, or social media photos of people on vacation in exotic locales, many people feel they have missed out on the outsized returns over the past decade and are trying to catch up.

This is precisely the reason the late Charlie Munger said, “it’s not greed that drives the world, it’s envy.”

The trouble is that when people take outsized risks at this stage of a cycle, it almost always doesn’t end well.

#2 — Stay well-informed and open to observations

Being “well-informed” seems to mean something different than it used to, in large part due to the speed at which information travels. For parents, it used to mean knowing their kids’ general whereabouts and trusting they’d be home by dark. Now, it involves tracking their every move with GPS. As for openness to feedback, since many now take offense, teachers and coaches often hesitate to provide it, hindering kids’ growth.

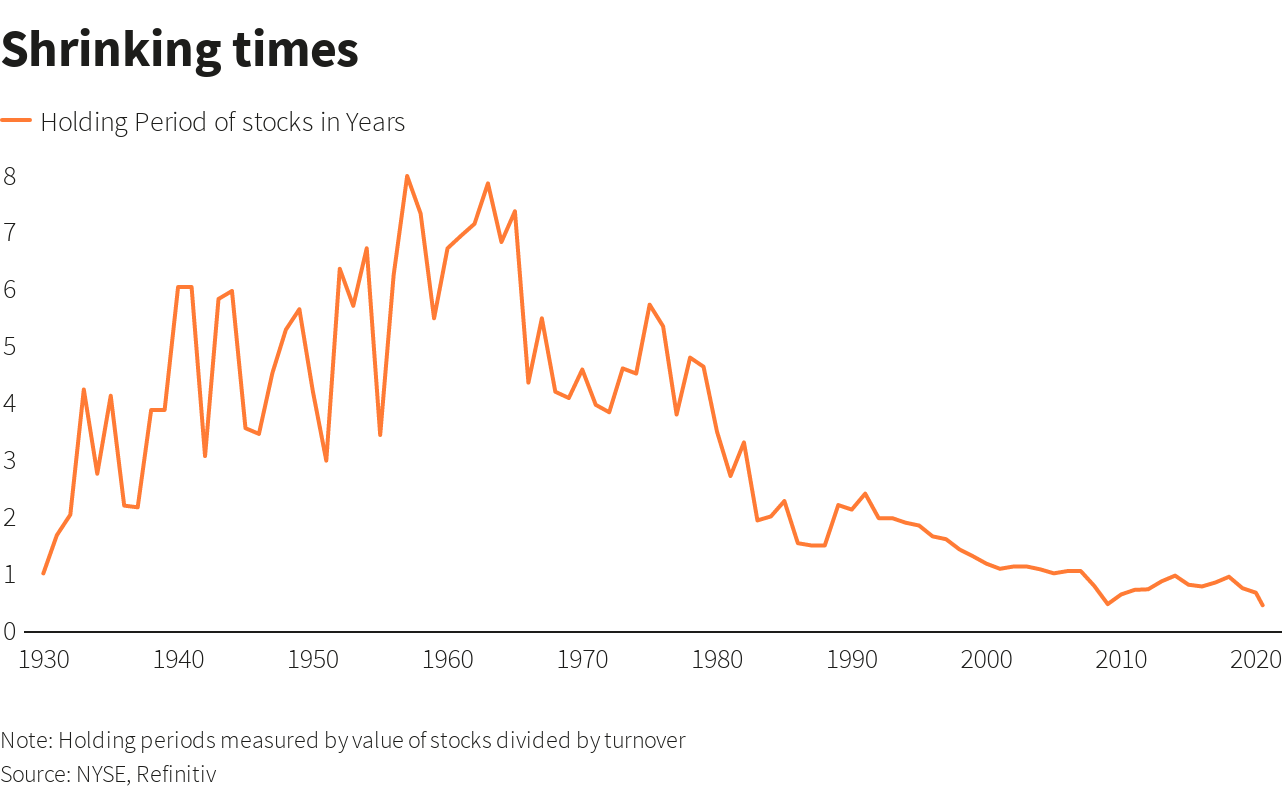

For investors, it used to mean being well-read and having a good sense of where the world was headed. Today, it too often means being aware of what is happening every minute of every hour of every day through outlets like Twitter and Bloomberg. Unfortunately, this deluge of information has made many “miss the forest for the trees,” leading to increased turnover and worse performance.

#3 — Accept “bad news” as a problem to be dealt with and don’t overreact

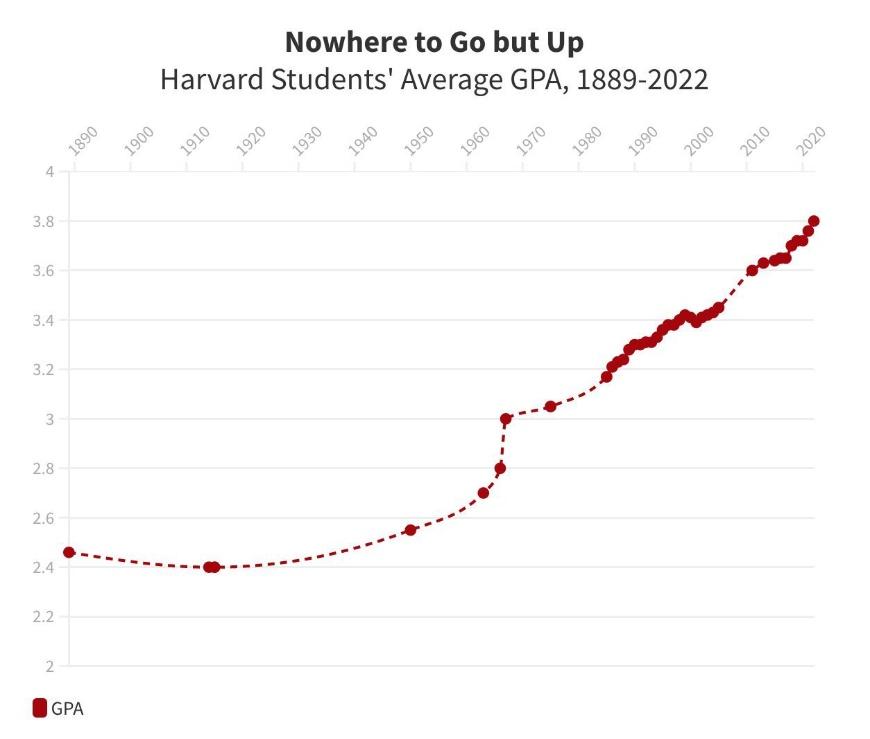

An inability to accept that bad grades are a part of life has led to one of the greatest overreactions in the history of education — grade inflation.

The result?

No one knows how kids are truly doing, notably colleges and employers. As a result, to gain admission, kids feel like they need to differentiate themselves in other ways, so they overload on countless activities outside of school. Yet, GPAs are still higher than ever.

Investors hate bad news too, only instead of grade inflation, we have experimented with illiquidity as a solution to the volatility created by negative headlines in public markets. The problem is, volatility is often what creates the best investment opportunities, at least for those able to take advantage of it. Given this push for illiquidity has become so widespread, we are just beginning to witness the side effects.

#4 — Listen carefully, but make the distinction between listening and agreeing

Listening and agreeing are vastly different things. Personally, with a nine- and seven-year-old at home who have been increasingly stretching the truth, I do a lot more listening than agreeing, but I imagine this will get more nuanced the older they get. In my experience, the best investors listen to everyone, but for a different reason than you might expect — they listen in order to determine what the current consensus is. Once they do, they often start leaning the other way…i.e., they don’t agree.

#5 — Leave the child some unscheduled time

Everyone knows our kids are overscheduled (see the consequence of grade inflation). After all, when getting into the best college or being offered a great first job is the “end-all-be-all” and only possible with endless activities, what do you expect? Yet, kids are more overwhelmed, anxious, and stressed out than ever.

As for markets, Morgan Housel has often said that his best thinking occurs when he goes for a walk. No iPhone. No podcasts. No music. Just himself walking. Try it.

#6 — Act consistently over time when parenting

As a dad, I will fully admit that I am not great at this. I have been known to threaten a punishment – “we’re leaving if you don’t stop doing that!” – but then back down, likely because I personally don’t want to leave. The problem is my kids have caught onto this and it’s a problem because like Clint Eastwood in Sudden Impact, they now call my bluff.

Most investors are equally poor at this. They are value investors one day, growth the next. Fans of active managers today, and passive tomorrow. In love with private equity, then out of it. Either way, the most reliable path to success is consistency. Pick one strategy and stick to it. Don’t flip flop, especially now. If you’ve held international equities for the past decade, I wouldn’t bail now. If you’re late to the game on private equity and considering an allocation, make sure you’re capable to sustaining new commitments for years to come. If you’re thinking about scrubbing any commodity or energy exposure you have left, I actually might consider adding instead.

So where does this leave us?

The fact is, as much as we tell ourselves that things are vastly different than they were a few decades ago, the reality is they aren’t. Sure, the world is faster, noisier, and more competitive, but the core tenets of a good life — or a resilient portfolio — haven’t changed. In fact, they might matter more than ever. Namely, as this lower school head suggested — keep your expectations in check, stay well-informed (but not too informed), avoid over-reacting, listen carefully, and remain consistent. Simple on paper. Hard in practice. Timeless for sure.

For all parents and kids out there, good luck in the new school year. I know I’ll need it.

For investors, I’ll say the same thing — good luck…we all need it.

2025-09-04 01:59:00

My new book, The Art of Spending Money, comes out Oct 7th.

Investor Chris Davis – who serves on the board of Berkshire Hathaway and Coca-Cola – says, it’s “not so much a sequel as the masterful, Oscar-worthy completion of” my first book, The Psychology of Money.

I wrote this book because I found there to be too much advice on building wealth but almost none on what to do with it.

This book is not called The Science of Spending Money because I don’t think such a thing exists. I’m more interested in the art of spending money. Art can’t be distilled into a one-size-fits all formula. Art is complicated, often contradictory, and covers things like individuality, greed, jealousy, status, and regret.

That’s what this book is about.

Now, I think you can use money to build a better life.

I think buying nice stuff can bring you joy.

I love ambition, hard work, and – most of all – independence.

But after writing about money for two decades, I am constantly amazed at how bad most of us are at knowing what we want out of money, or how to use it as anything more than a benchmark of status and success.

I try to tackle the art of spending money from several angles. But you’ll find a few common denominators in this book:

1. There are two ways to use money. One is as a tool to live a better life. The other is as a yardstick of status to measure yourself against others. Many people aspire for the former but spend their life chasing the latter.

2. Money is a tool you can use. But if you’re not careful, it will use you. It will use you without mercy, and often without you even knowing it. For many people, money is a financial asset but a psychological liability. Blind lust for more can hijack your identity, control your personality, and wedge out parts of your life that bring greater happiness.

3. Spending money can buy happiness, but it’s often an indirect path. Money itself doesn’t buy happiness, but it can help you find independence and purpose – both key ingredients for a happier life if you cultivate them. A big, nice house might make you happier, but mostly because it makes it easier to have friends and family over, and the friends and family are actually what are making you happy.

4. Enduring happiness is found in contentment, so those happiest with money tend to be those who have found a way to stop thinking about it. You can value it, appreciate it, even marvel at it. But if money never leaves your mind it’s likely you’ve found yourself with an obsession, where it controls you. The best use of money is as a tool to leverage who you are, but never to define who you are.

5. If you’re confused about what a better life would look like, “one with more money” is an easy assumption. But that can sometimes mask deeper problems. Money is so tangible that it’s an easy goal to strive for, and pursuing it can become the path of least resistance for those who haven’t discovered what truly feeds their soul.

6. Everyone can spend money in a way that will make them happier. But there is no universal formula on how to do it. The nice stuff that makes me happy might seem crazy to you, and vice versa. Debates over what kind of lifestyle you should live are often just people with different personalities talking over each other. Author Luke Burgis puts it another way: “After meeting our basic needs as creatures, we enter into the human universe of desire. And knowing what to want is much harder than knowing what to need.”

The book comes out October 7th. I hope you enjoy reading it.