2026-02-03 16:38:41

Welcome to this edition of our Tools for Thought series, where we interview founders on a mission to help us think, connect, and live better. This week, we talked to Carly Valancy, founder of TETHER and Reach Out Party.

In this interview, we talked about meaningful connections as a competitive advantage, how to experiment with connecting with others, how to treat your network like a garden, and much more. Enjoy the read!

Hi Carly, thank you for joining us. You’re passionate about helping people make meaningful connections. Why do you think this is so important?

When I started my career, I reached out to one person every day for 100 days and it changed my life. I realized that we have so much more agency over who we know than we think, or want to think. I learned that you don’t have to be in the right place at the right time to make meaningful connections. Your network isn’t some fixed inheritance. It’s alive, like a garden is alive. When you feed it and tend to it, it will grow in ways you couldn’t have imagined. When you neglect it, it will wilt.

Our lives literally are made up of the relationships in them. Life really is about who you know. When you break down what is such a common cliche, you find a deep truth underneath it.

I believe meaningful connections are the ultimate competitive advantage in a world increasingly mediated by screens and algorithms and AI. Our ability to build genuine human relationships has always been important, but it’s able to become even more valuable.

How did you come up with the idea for TETHER?

I moved to NYC to pursue a career as an actor, at the bottom of a very hierarchical industry. As an attempt to break out of this system, I conducted an experiment to reach out to one new person every day for 100 days. The experiment changed my life. In those 4 months, I found opportunities that would have taken me years to find and I tracked it all in a chaotic Google spreadsheet that became a tangled mess of names and context.

Tracking gave me incredibly interesting data. I knew what my response and rejection rate was. I could see what was working and what wasn’t. Aside from actually making connections, tracking those connections led me through pivots from theatre into tech into starting my own business. But the more I used it, the more I could feel connections slipping through my fingers. Following up was impossible, and every time I opened it, I felt overstimulated.

I tried using traditional CRM tools, but they felt gross… So I just stopped keeping track. For years. And once I stopped keeping track, I stopped reaching out. And slowly, all of these beautiful seeds I’d planted started wilting.

TETHER was born from this tension: I needed a system that was intentional. That helped me stay organized but allowed me to stay creative. And that motivated me to keep showing up. Something that honored the messiness and magic of real human connection while still giving me structure.

What started as a simple Notion template for myself, turned into a whole operating system that I started sharing with others. It is a system that will help you pay attention to making connections.

A tether is the gentle support system that guides a plant’s growth, prevents it from falling over or growing uncontrollably. That’s what I’ve always wanted for my network. Something that steers growth in a specific direction while leaving room for serendipity.

You built TETHER for “extroverted introverts” – what does that mean?

Okay, so I genuinely love people. I love the energy of a good conversation, the serendipity of meeting someone new, the way a single email can change the trajectory of your life. That’s the extrovert part.

But I also find traditional networking exhausting and overstimulating and performative. Making many surface level connections feels transactional and makes me want to hide. That’s the introvert part.

Extroverted introverts are people who want depth in their relationships. They want to connect but often feel overwhelmed or icky about how they’re “supposed” to do it. They know relationships matter, but the whole networking industrial complex feels soul-sucking.

The ideal TETHER user is someone who knows they should be reaching out more but keeps putting it off because it feels like a chore.

What I’ve learned is that a lot of very ambitious, very creative people avoid networking not because they’re antisocial, but because the systems we’ve been given are not made for us.

What’s the difference between Tether and existing CRM tools?

Most CRMs are built on this philosophy: reach as many people as quickly as possible, track them through stages, automate sequences, optimize for some kind of outcome or conversion.

TETHER is the opposite. It’s built for human beings prioritizing clarity, intention, and generosity over spammy outreach. It’s like a beautiful container for serendipity to grow.

When you open TETHER, you see your goals, your connections, and prompts to be thoughtful about who you want to reach out to and why. It is designed for individuals who want to grow their network intentionally, whether that’s freelancers, founders, writers, artists, or anyone navigating a career transition.

Being a Notion OS, the automations are simple. The point isn’t to remove friction from reaching out, it’s to make the friction meaningful. When you sit down to send a message through TETHER, you’re making a conscious choice to prioritize connection as a practice.

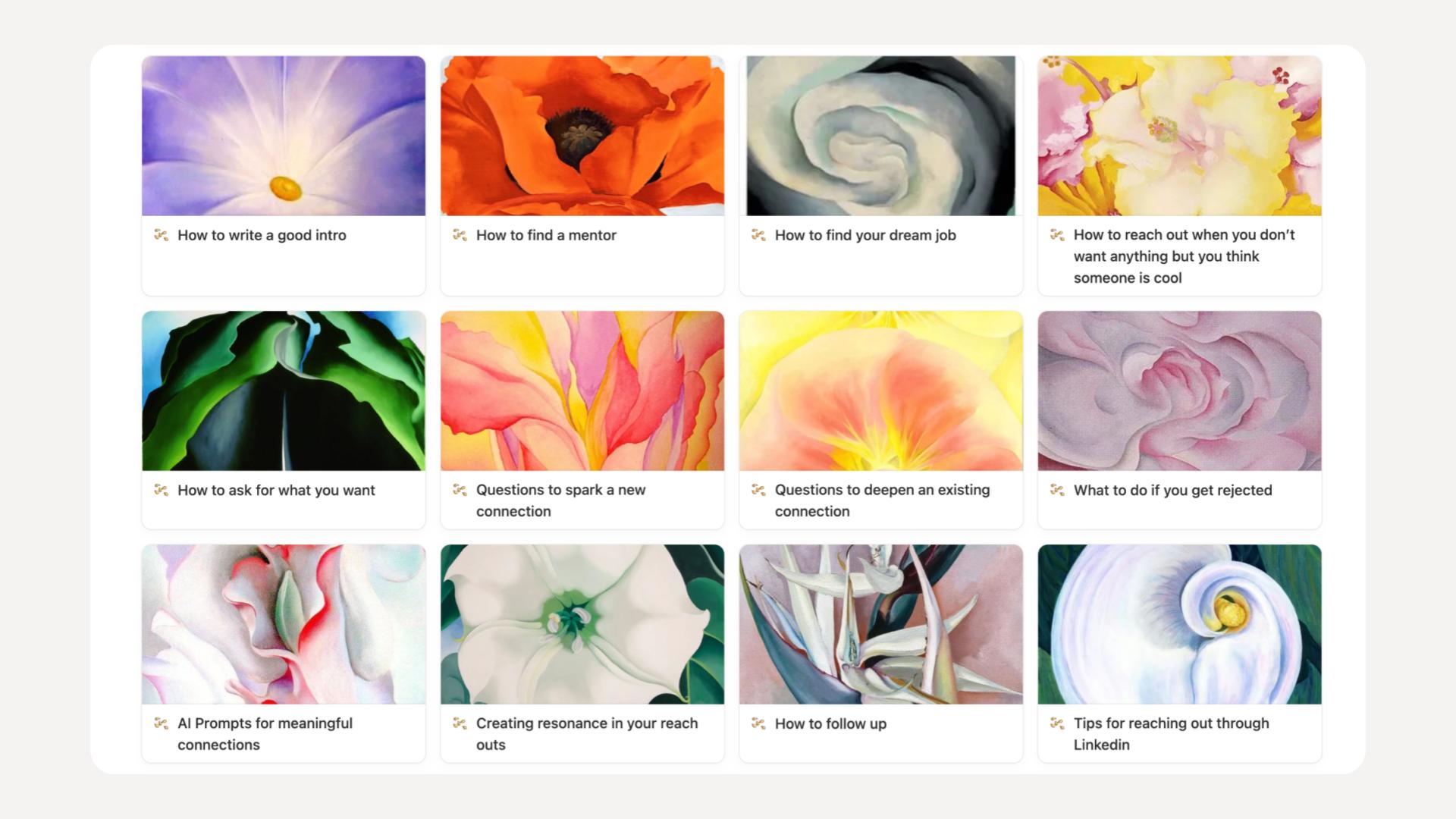

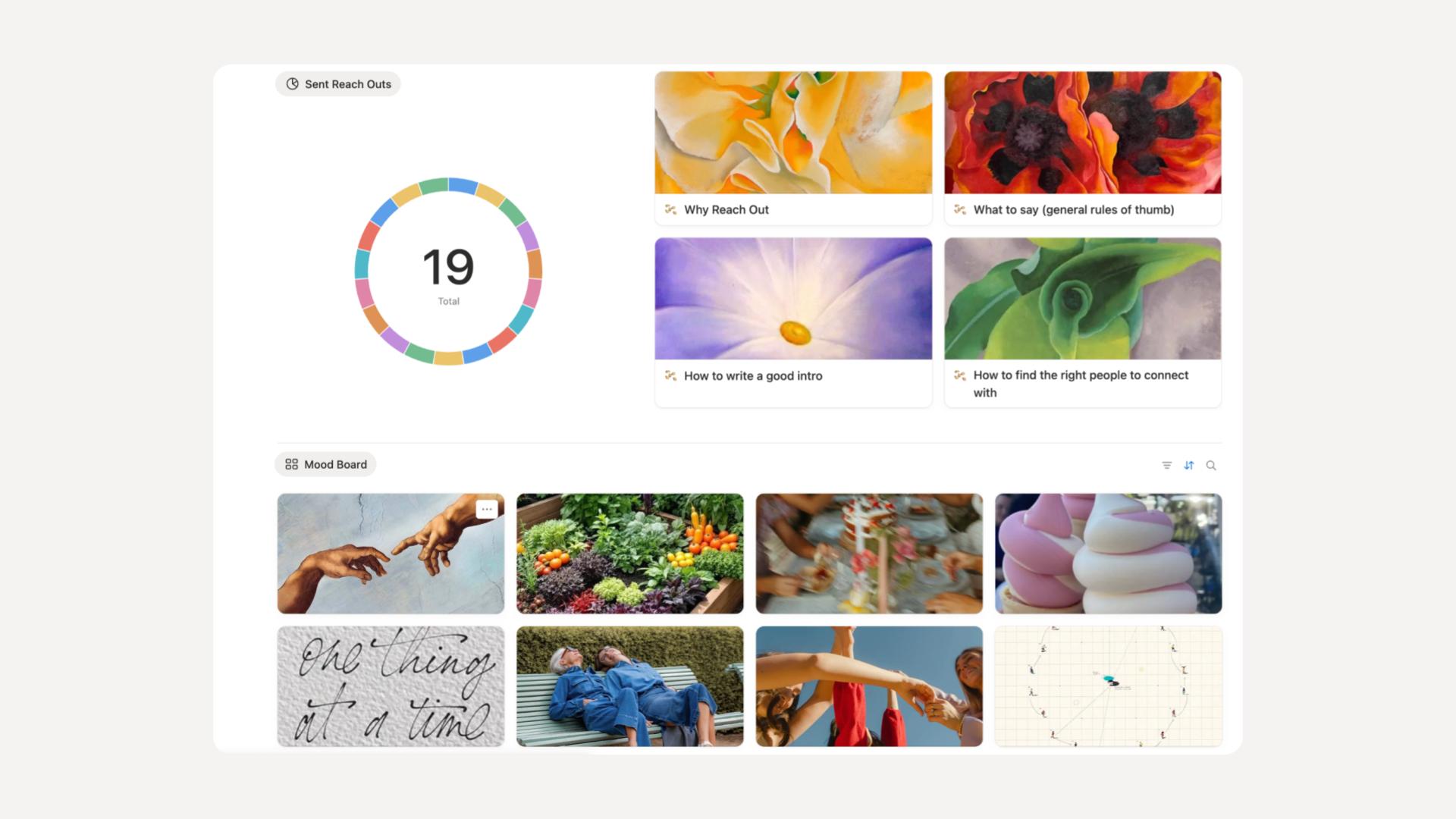

It includes a resource center, challenges, a gorgeous way to view your data, and goal-setting frameworks. And of course, it is full of Georgia O’Keeffe artwork, ensuring that your nervous system is instantly soothed every time you open it.

Let’s talk about how TETHER works in more detail.

When you first open TETHER, you start with your goals, intentions, and values. I recommend three goals, two professional and one personal. These will help you find clarity on who you should be reaching out to. These goals serve as a constant reminder for what you want your network to help you achieve.

The main dashboard shows you your “Reach Out Tracker” which is where the magic happens. Instead of a traditional CRM’s intimidating spreadsheet of contacts, you see a curated view of people organized by how they relate to what you’re trying to accomplish.

The Reach Out Tracker is where you log who you’ve reached out to, when, and whether they responded. Over time, it becomes this beautiful record of all the seeds you’ve planted.

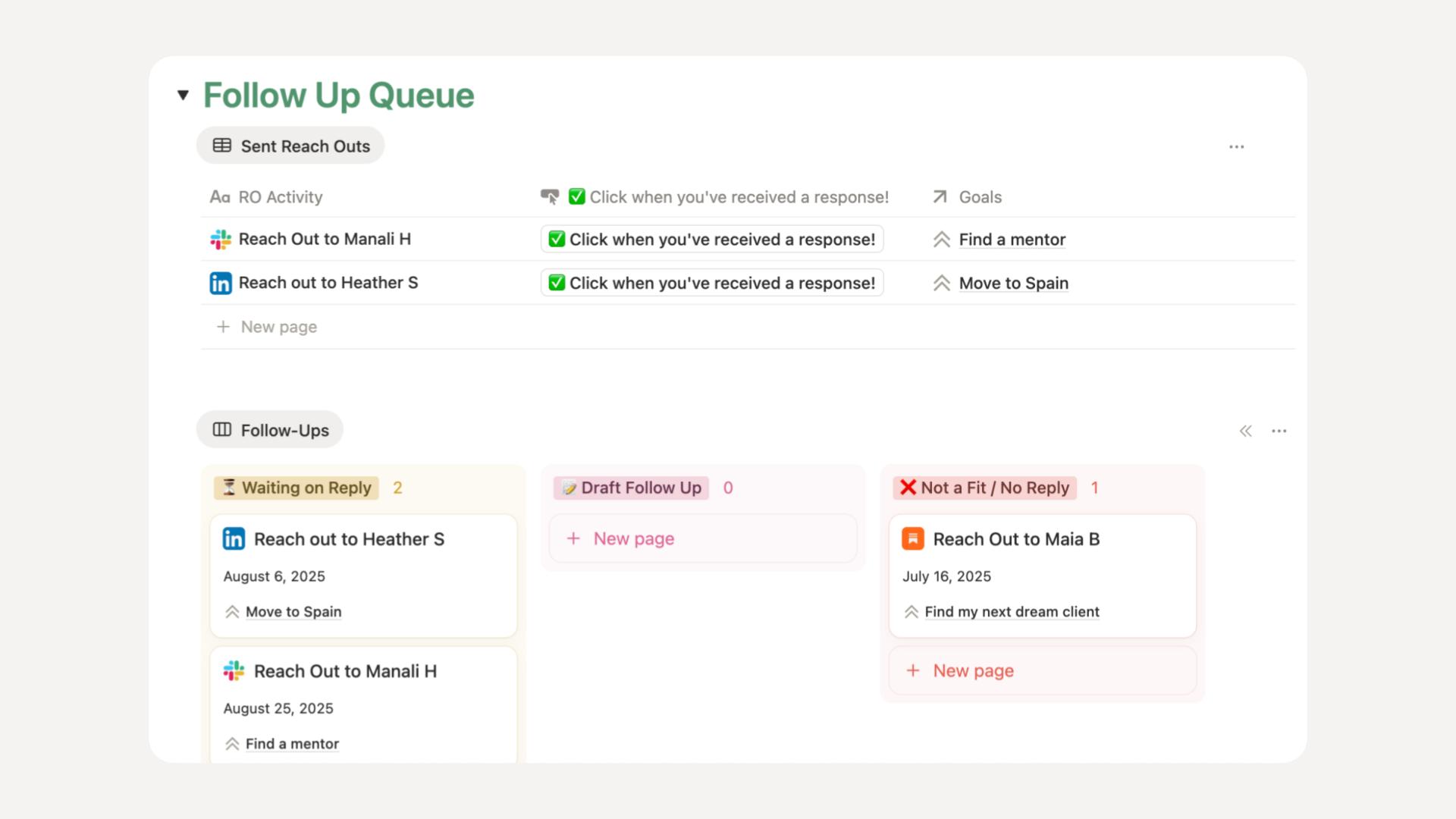

Once you receive a response, they move into the Nurture Queue, where you can decide whether there is any action needed or whether you just want to move them into a Keep In Touch folder for the future. If you don’t receive a response for over one month, connections will be filtered into a Follow Up Queue so no one unintentionally slips through the cracks.

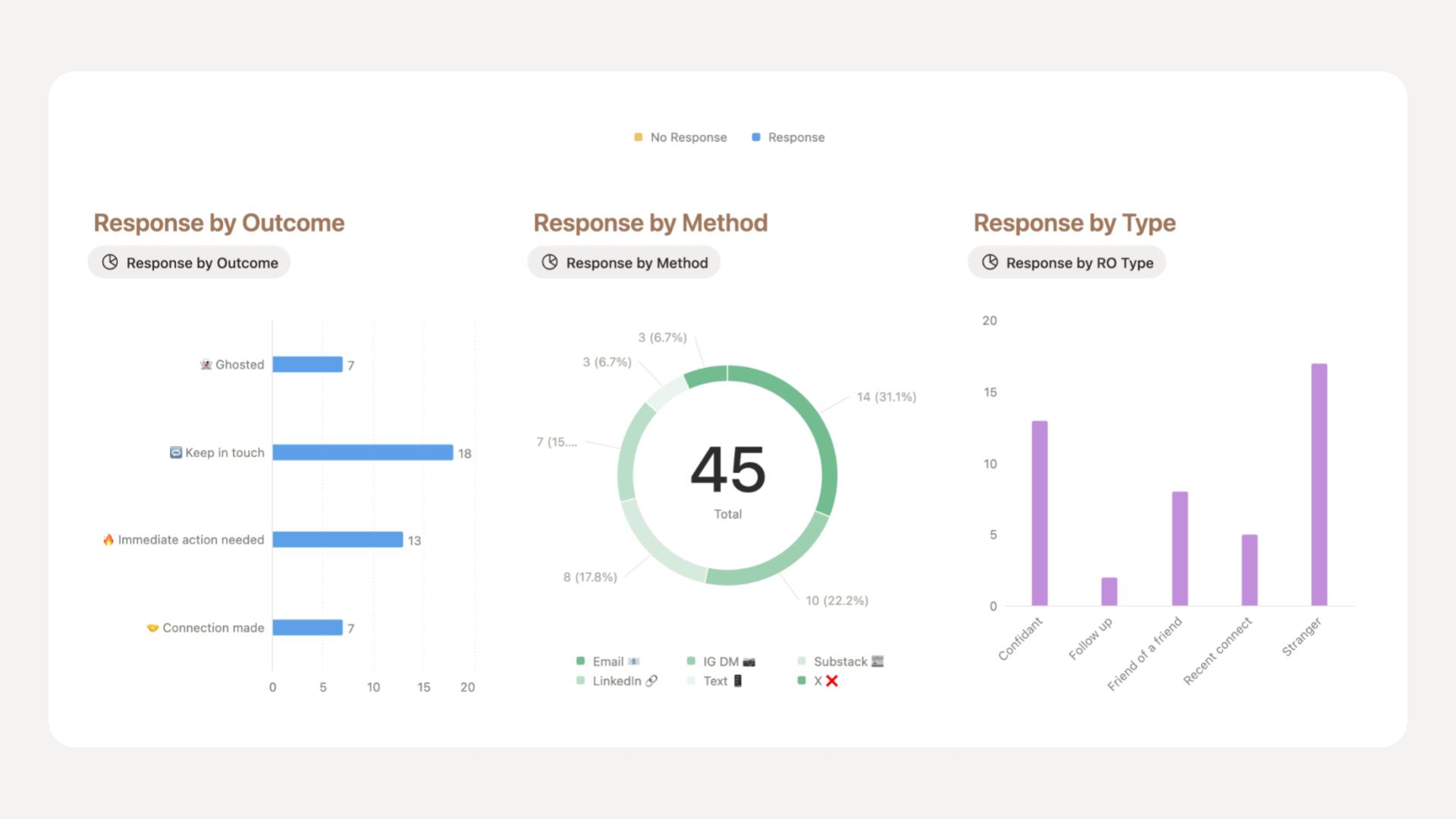

There’s a Data Plot feature that visualizes your progress and shows you your results in real time. You can track response rates, rejection rates, and most importantly, just see that you’re doing the thing consistently. That visibility is motivating.

The Resource Row is a growing collection of tips, examples, and templates. Real examples of messages that worked (and some that didn’t), frameworks for different scenarios, prompts for when you’re stuck. It’s designed to make digital networking feel soft and warm instead of cold and scary.

There’s also a Mood Board for collecting good vibes and a Challenge Center for those of you who like tiny experiments.

Who is using TETHER today and what are some of the main ways they’re using it?

Creative people. Artists, writers, freelancers, consultants, founders, investors, portfolio-careerists. TETHER’s functionality adapts for anyone in any industry, but works best for people that are ready to change their relationship to networking.

One pattern I love is that lots of people seem to be using TETHER to navigate big life changes, from career pivots to moving to a new city.

Some people do daily challenges like I did originally. Others commit to weekly. Some use it more for maintenance, checking in to make sure important relationships don’t slip through the cracks.

What about you, how do you personally use TETHER?

I’m currently in the middle of my second 100-day challenge. Reaching out to one person every working weekday.

My daily rhythm looks like this: I open TETHER and head to my tracker. Sometimes I have a few new people in the queue, sometimes I’m following up, sometimes I come across someone totally unexpected I want to reach out to.

Most days, the reach out itself takes about 20 minutes total. Even though I believe in the value of this practice so much, most days I still really don’t want to do it. It takes a lot of emotional energy to put yourself out there knowing you could be rejected.

I come back to TETHER once I’ve hit send and celebrate my progress before clicking out of it and continuing with my day!

What I love about using it myself is seeing my progress compound. It keeps me showing up. After 50+ days of consistent reaching out, my response rate, my confidence, and my sense of what works have all improved dramatically. I can see patterns I never would have noticed otherwise.

Looking ahead, how do you see TETHER evolving over the next few years?

I believe that treating connection as a practice can change your life, and I want to help as many people as possible experience that.

In the near term, I’m focused on building out the educational component. More templates, and frameworks for specific goals and situations. I’m also developing a more built out version for Reach Out Party, my mastermind that pairs TETHER’s system with accountability and coaching for reaching specific goals.

Longer term, I look forward to building software to support more ways to treat our network like the gorgeous garden it can be.

What I’m most excited about, honestly, is the cultural shift I’m starting to see. More people wanting genuine connection. TETHER is one tiny part of a larger movement toward building intentional relationships.

I really believe the future belongs to those who invest in soft skills. As AI makes automation the norm, our ability to build real human relationships becomes the ultimate edge. I want to be part of helping people develop that edge. Not through hacks, but through the slow, beautiful, compounding practice of reaching out.

Thank you so much for your time, Carly! Where can people learn more about Tether?

Thanks for having me! You can learn more about TETHER on the website, Substack, LinkedIn and Instagram. There’s also a dedicated page with more information about Reach Out Party. I’ve got about 4 spots left for the cohort that starts in March 2026. If you mention Ness Labs in your application, you’ll get $100 off.

The post Nurture your network with Carly Valancy, founder of TETHER and Reach Out Party appeared first on Ness Labs.

2026-01-29 21:37:58

Welcome to this edition of our Tools for Thought series, where we interview founders on a mission to help us think better and work smarter. Dr George Sachs is the co-founder of Inflow, a science-based app created by ADHD clinicians and psychologists. In this interview, we talk about the importance of self-reflection, strategies for time management and task initiation, the power of combining psychoeducation and practical tools with in-the-moment support, and much more. Enjoy the read!

On your site, you describe Inflow as a program built specifically around ADHD and executive function challenges. How did that specific audience shape your approach to design and development?

A lot of my work, as a psychologist and through Inflow, is about helping people shift the way they relate to their brains. Many people come to ADHD support believing they are disorganized or lazy, when in reality they are dealing with a brain and nervous system that processes attention, time and motivation differently.

Understanding your neurodivergent brain is not about labeling yourself or lowering expectations. It is about gaining clarity. For many people, that process starts with simply reflecting on their own patterns. When you understand why certain things are hard, you can stop wasting energy fighting yourself and start designing your life in a way that actually works for you. From personal experience, I know that this kind of understanding can become the foundation for healthier productivity and emotional wellbeing.

The idea for Inflow grew out of my clinical work with people with ADHD. I realized that in therapy, I could teach skills and offer psychoeducation, but that kind of support is expensive, time consuming and simply not available to most people who need it.

I wanted to build something that could help any adult struggling with ADHD-related challenges. A tool that was evidence-based, but also honest about how ADHD shows up in real life.

Before we ever built the app, my co-founders and I spent a lot of time speaking directly with people living with ADHD. We ran interviews, talked to early users, and built an initial waitlist that grew to over 10,000 people. Those conversations shaped what we built and how we built it.

Our founding team and early contributors included perspectives from clinicians alongside people with lived experience of ADHD, so everything was shaped by clinical evidence and real-world use from the start.

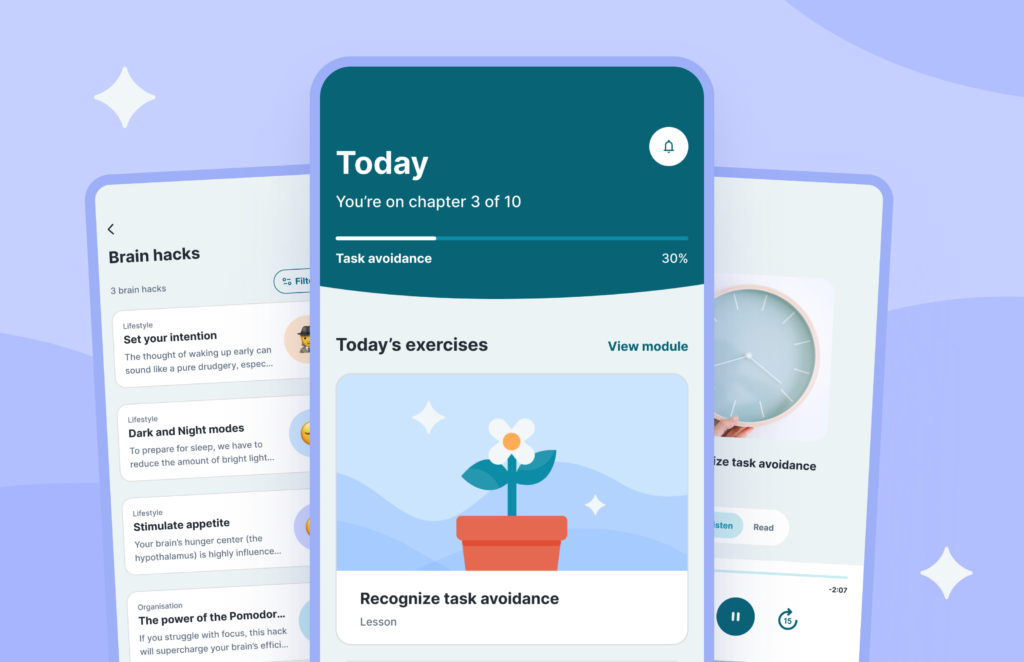

We knew long lessons, dense language or rigid programs would not work. Instead, we focused on short, focused lessons that translate directly into everyday life. We use language that feels accessible and nonjudgmental.

We are intentional about grounding the product in research, not just theory. Inflow has been evaluated through a usability and feasibility study and more recently in a randomized controlled study exploring how people engage with the app and how it may support everyday functioning. Participants reported improvements in areas like quality of life, organization, time management, and planning skills, particularly among those who engaged more deeply with the app.

Let’s talk about how Inflow works. The app combines educational content, in-app exercises, and coaching-style tools. Why did you choose that format instead of, say, a traditional course or a simple planning app?

Before we even thought about app features, we spent a lot of time listening. Listening to the community, listening to potential users, and reflecting on our own lived experience of ADHD. What became clear very quickly was that most people were not failing because they lacked information. They were struggling because support was fragmented or built around assumptions that did not match their reality.

That insight shaped a lot of what came after. We were not trying to build the most comprehensive course or the most powerful productivity system. Our goal was to help people understand themselves better, reduce shame and build self-acceptance alongside practical support for ADHD.

For many people with ADHD, habit-building on its own can feel like another place to fall short if they do not understand why certain things are hard in the first place.

That is why Inflow is designed as specialist ADHD support rather than a traditional course or planning app. The app combines short, evidence-based psychoeducational modules that help people make sense of how ADHD affects things like time perception, task initiation and emotional regulation, alongside in-app exercises and interactive elements that let them practice skills in real life.

We think of Inflow as an evidence-based ADHD self-help app designed to complement clinical care when someone has access to it, and to offer structured, evidence-based self-help support when they do not.

ADHD is not consistent from day to day, so support cannot be either. People need something that is flexible and easily accessible that helps them respond to what is actually happening today.

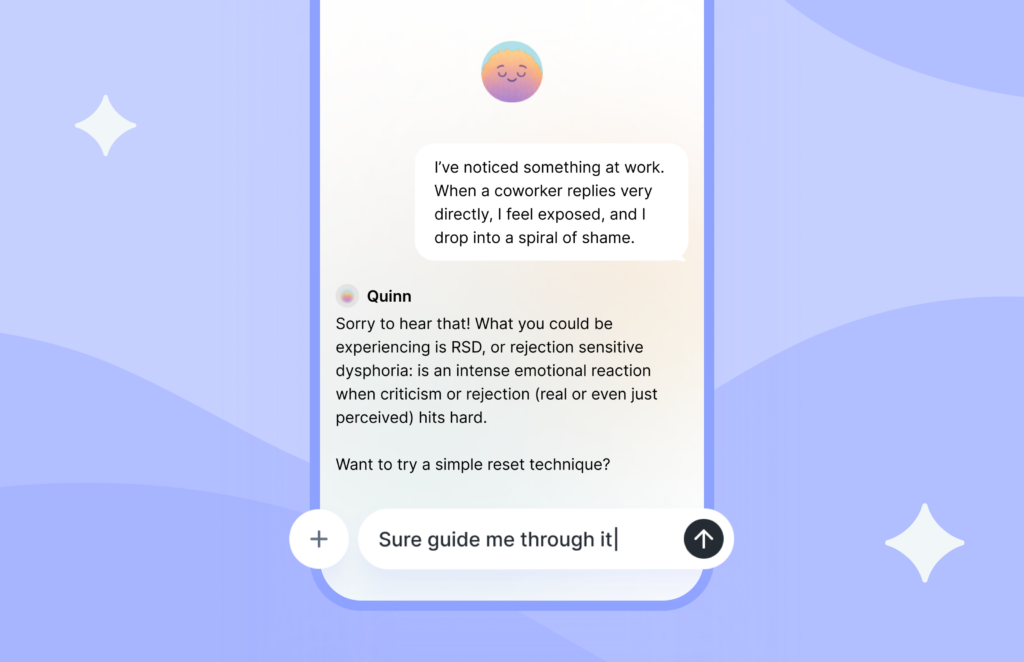

Alongside this, Quinn, our AI-driven support, helps bridge the gap between learning and action. It allows people to ask questions about the content, think through priorities when they feel stuck, and reflect on emotional patterns in the moment. Rather than offering generic advice, Quinn is designed to support reflection and decision-making. We see it as a responsible use of AI that augments human understanding rather than replacing it and one that can be a gamechanger for individuals with ADHD-related challenges.

Again and again, users told us they did not want another system to keep up with or something they would procrastinate on and eventually abandon. They wanted support that felt flexible, forgiving and responsive to real life.

By combining psychoeducation, practical tools, and in-the-moment support, we were able to design Inflow to work with ADHD rather than against it. At its core, the app is about helping people move from understanding to action in a way that feels sustainable and compassionate.

For us, that balance between clinical grounding and real-world usability continues to guide how we evolve the product. Inflow has been evaluated through a usability and feasibility study and more recently through a randomized controlled trial that showed meaningful improvements. For us, that balance between evidence and real-world usability is critical.

In the app and on your blog, you talk about approaches like breaking tasks into very small steps, using visual timers, and body doubling for focus. Why did you decide to emphasize these particular strategies?

We emphasise those strategies because they map very closely to how ADHD brains process time, attention and task initiation. Challenges like time blindness, task paralysis and distractibility are core features of ADHD. They are not about effort or intention, but about how the brain regulates focus and translates intention into action.

Strategies like breaking tasks into very small steps, using visual timers and body doubling work because they provide external structure for processes that are less reliable internally for people with ADHD.

A visual timer helps make time tangible for an ADHD brain that struggles to sense it passing. Breaking tasks down lowers the activation energy required to start when initiation feels stuck. Body doubling supports sustained attention by adding a gentle external anchor rather than relying on internal motivation alone (something ADHDers really struggle with).

We chose to build product features and lessons around these approaches because they consistently help in both clinical practice and lived experience. Standard to-do lists assume that remembering, prioritizing, and starting tasks are the main challenges. For many people with ADHD, the difficulty is actually initiating, staying engaged and re-engaging when attention drops.

By designing around how ADHD brains work rather than how they are expected to work, the Inflow app offers sustainable support for everyday life for adults with ADHD.

Who is using Inflow today, and what are some of the main ways they’re using it?

We see a very broad range of people using Inflow today. Some are newly exploring ADHD and trying to understand patterns they have struggled with for years. Others were diagnosed a long time ago but still feel overwhelmed by day-to-day life, and are looking for support that feels practical and sustainable.

People use the app in different ways depending on where they are and what they need in the moment. For many, what brings them to Inflow is a period of overwhelm, when things start to feel unmanageable and they’re looking for a way to slow down and find their footing again.

Some focus on routine-building, time awareness and task initiation. Others use it more for emotional regulation, understanding overwhelm, rejection sensitivity or burnout. This can support their own wellbeing and contribute to healthier relationships over time. For many, simply having language for experiences they have never been able to explain before is a meaningful starting point.

Quinn, our AI-driven support, also plays a key role here. It helps personalize and contextualize the experience day to day by allowing users to ask questions about the content, reflect on what is going on emotionally, and think through how a strategy applies to their specific situation. It helps bridge the gap between learning something and actually putting it into practice.

For many users, one of the most meaningful outcomes is simply feeling less alone. The community board and the daily rotating question give people a low-pressure way to reflect and see that others are dealing with similar challenges.

We also see a lot of people getting real value from body doubling sessions. For some users, that shared structure and presence makes a noticeable difference for focus and follow-through, especially when working alone feels isolating or overwhelming.

Most people do not use just one feature in isolation. That flexibility is intentional, because ADHD needs can change from moment to moment.

What about you, how do you personally use Inflow, if at all?

I use Inflow in much the same way many of our users do. Not as something I engage with perfectly or consistently, but as a support I return to when I need it.

I often use the psychoeducational content as a reminder rather than as new information. When I notice myself getting frustrated or stuck, revisiting a short lesson can help me reframe what is happening and respond with more compassion.

I also use Quinn to think through priorities when my head feels cluttered or when I am emotionally charged and need help slowing things down.

What has probably surprised me the most is how much Inflow has reinforced something I already knew as a psychologist but sometimes forget in daily life. Support does not have to be all or nothing to be effective. Even brief moments of reflection or structure can make a meaningful difference.

Using Inflow has deepened my belief that ADHD support works best when it is integrated into real life rather than treated as something separate you have to keep up with.

Looking ahead, how do you see Inflow evolving over the next few years?

Looking ahead, our focus is on deepening personalization and making support more responsive to where someone is in the moment. ADHD is not static and support for it shouldn’t be either. We want Inflow to adapt to users’ patterns, needs and goals over time, rather than offering a one-size-fits-all experience.

A big part of that work is recognizing that ADHD-related challenges often show up alongside other experiences. Many people are navigating anxiety, low mood, burnout, sleep issues or difficulties with emotional regulation and those factors can meaningfully shape how executive function challenges show up day to day.

Inflow is designed to be inclusive and accessible, and people do not need a formal ADHD diagnosis to benefit from the support.

We are continuing to expand our content and tools to better reflect this broader picture, so support feels relevant to the person rather than tied to a single label. Many users are also reflecting more broadly on their neurodivergence and wondering whether some of the traits they recognize might relate to autism, or other overlapping experiences. Rather than focusing on diagnosis, our approach is to help people understand patterns in their lived experiences in a grounded and responsible way.

That perspective also shapes how we think about personalization. We are expanding the role of Quinn as a guide that helps people connect insights across the app, reflect on what is working, and adjust strategies over time without feeling like they are starting from scratch.

Personalization, for us, means meeting people where they are and responding to their capacity, context and emotional state, not pushing them toward a fixed idea of productivity or functioning. More broadly, we want to continue expanding beyond narrow ideas of productivity. Executive function challenges affect every area of daily life. From work and creativity to relationships, rest, self-esteem and mental health. Our long-term vision is for Inflow to support people across those domains in a way that remains grounded in clinical evidence and consistently human and usable. Over time, we see Inflow playing a role in a more connected care ecosystem, helping people bridge between everyday self-support and clinical or telehealth care in a way that feels clearer and more integrated.

Thank you so much for your time, George! Where can people learn more about Inflow?

Thanks for featuring Inflow. For readers who want to reflect more deeply on how ADHD might show up in their daily lives, Inflow’s free ADHD traits quiz is a good place to start.

The post Understand your neurodivergent brain with Dr George Sachs, co-founder of Inflow appeared first on Ness Labs.

2026-01-22 18:16:42

Jan 21, 2026 | Watch on YouTube | Download the transcript

When Dr Anne-Laure Le Cunff was told she might die, her first instinct was to check her calendar. In this talk, she reveals how our desperate need for control keeps us stuck and how tiny experiments can set us free. Dr Anne-Laure Le Cunff is a neuroscientist, author, and entrepreneur who studies curiosity – both in the lab and in life. Her research at King’s College London explores how our brains seek, learn, and adapt, spanning areas from ADHD to AI and mental health. She founded Ness Labs, a science-based learning platform helping people live more experimental lives. Her bestselling book Tiny Experiments offers a practical guide to transforming uncertainty into curiosity, creativity, and self-discovery. Through her research and writing, she bridges science and everyday life, showing how curiosity can help us loosen control, embrace change, and uncover who we truly are.

In that moment, despite the seriousness of the diagnosis, or perhaps because of it, I wanted to feel in control. I wanted to believe that I could stay in charge of what happened next. And so when I heard the news, instead of shifting my footing, I held on tighter to the calendar, to the identity of being the one who never falls behind.

I’m sure you’ve had your own version of that moment when something cracked open in your life and your first instinct was to ask, “How do I stay in control?” In those moments, we tell ourselves, “I’m the productive one. I’m the calm, the quiet, the supportive one, the one who never drops the ball, the one who always has it together, the one who keeps everyone happy.” We all carry these deep assumptions about who we are. And when life feels uncertain, we tighten our grip, not just on the situation, but on the identity we’ve built.

So, here’s the question I’d like to explore with you. What if the thing keeping you stuck isn’t your circumstances, but your grip on who you think you need to be? Let me explain how that works. Our minds crave a sense of order. So, when real control disappears, the brain will manufacture an artificial sense of control however it can. That’s why when things feel uncertain, we reach for anything, absolutely anything that helps us feel steadier. How many of us have added another app, another routine, another system when life felt chaotic? We all do this to the point where this behavior has a name.

Psychologists call it compensatory control, which is our attempt at restoring order by creating structure, even if it’s artificial. And we’re not just wired that way. We’re trained this way. Our schools and our societies reward us for being prepared, for being certain, for being right. And so when things feel wobbly, we try to escape that liminal space as quickly as possible rather than pausing to explore.

And now here’s the tricky part. In the short term, it feels like it works. Predictable structures help lower the perceived threat and downregulate the stress response. Planning feels responsible and productive, so you feel a bit calmer, and yes, in control. But over time, this artificial sense of control narrows your options.

You can’t receive what life is actually offering when you’re too busy managing what you think it should be offering. And when you’re trying to control everything, you leave no room for discovering anything, including about yourself. And that’s the real trap. Control doesn’t just keep us stuck in our circumstances, it keeps us stuck in our current identity.

So if control isn’t the answer, what is? That’s what I started wondering after this absurd moment at the hospital. And I know, I know that in that kind of talk, you’re supposed to say that you had a big breakthrough. But in my case, the shift came from something a bit smaller. It came from a little bit of experimentation.

See, as a neuroscientist, I’ve been trained to conduct experiments in the lab. But I’ve come to realize that experimentation is much more than just a scientific method. It’s everywhere. It’s how nature evolves. It’s how species adapt. It’s how we learn to walk and talk as children. Experimentation is the fundamental way life moves forwards.

And there’s something in particular that’s very interesting about experimentation, something that can help us move forward while loosening our grip. The thing is, we don’t run experiments to get to a specific outcome. If we already knew the outcome, there would be no point running the experiment in the first place. We experiment to learn something new, whether that’s a new data point, a clearer picture of reality. Instead of asking how can I stay in control, we ask what can I try?

So if compensatory control is really about clinging to what you know, or what you think you know, experimentation is about letting go of the illusion of certainty. So I started wondering, how can we take this experimental mindset out of the lab and into our daily lives? The beauty of lab experiments is in how actionable they are. You know exactly what you’re going to test and how you’re going to test it.

And it turns out you can bring that same sense of forward momentum to your everyday life by distilling your own experiments down to just two essential elements. Just like a scientist who needs to know, first, what they’re going to try, and second, the trial period. You can choose a specific action to experiment with for a specific duration. I call these tiny experiments, and they follow a very simple formula. It’s like a mini protocol where you just say: I will [action] for [duration].

That’s it. This is not a habit. You’re not committing to this for the rest of your life. This is not a goal either. You’re not trying to get to a specific outcome. This is just an experiment. No targets, no success metrics, no illusion of certainty, just the courage to be curious for a moment and to step outside the story you’ve been telling yourself about who you need to be. Let me show you what that looks like in practice with a few examples from people I worked with.

I’m going to start with Jay. Jay was stuck in that familiar spiral that I think we’ve all experienced, so busy with work that he had lost touch with many of his friends. Weeks turned into months of radio silence. But every time he thought about reaching out, he’d freeze up and tighten his grip. He thought he had to craft the perfect message, to find the right timing, the perfect words to explain everything. And obviously all of this overthinking just kept him stuck. So instead, he said, “I will message one friend every week for four weeks.” No perfect apology, no grand explanation, just a tiny experiment.

What happened? Well, his friends were generally happy to hear from him. Nobody demanded an explanation or an apology or made him feel guilty about the silence. And now here’s what really shifted. Jay started seeing himself as someone who belonged in those friendships, even after the silence, not someone who needed to earn his way back in.

I have thousands of examples from people from my community. People who painted watercolor for 20 minutes every day. People who practiced saying no for just 24 hours. People who stopped consuming social media content for 5 days. And each and every one of them, in the process of experimenting, discovered something unexpected about themselves.

I’m actually one of those examples. When I started writing online, I was pretty anxious. I thought, I’m not a writer. English is not even my first language. And my instinctive response to that anxiety was control. To craft the perfect plan with subscriber targets, a content calendar, marketing strategies. But having learned everything that I had learned about the power of experimentation, I decided to apply an experimental mindset and I said: “I will write one short essay about neuroscience every day for 100 weekdays.” Again, no specific goal other than learning more about the world, about my work, and about myself and the process.

That shift from control to curiosity changed everything. I discovered a new professional path and parts of myself I hadn’t fully known yet. All because I decided to let go of that limiting fixed sense of identity and to experiment instead.

[Pause] So, huh… Let me take a deep breath. That wasn’t planned but that’s experimentation too. When I started experimenting, I also experienced an immense sense of freedom… Just like what I just did. Because when you start experimenting, when you start approaching life like a scientist, you break out of binary thinking. There’s no success or failure, right or wrong, fixed or broken. All you do is collect data. There is no imaginary leaderboard. All there is is your own personal laboratory.And now here’s the fun part. The uncertainty that once felt threatening starts feeling energizing. Just like a scientist, not knowing becomes exciting. There’s almost a sense of… An anticipatory quality, a sense of juiciness. What will I discover? What will I learn? And this is what makes those experiments very powerful.

In that way, experimentation rewires your relationship with uncertainty instead itself. Instead of trying to control everything, you let go of this illusion of knowing what happens next. Instead of forcing answers, you give yourself space to learn. And that very same uncertainty that once triggered your need for control becomes a doorway for discovery.

But now, what if you’re so frozen that even a tiny experiment feels impossible? What if the problem is so charged that you can’t even get close to it? This is when, and I know this is going to go against every instinct you might have, but this is when you need to loosen your grip even further by letting go of solving the problem directly.

Not all experiments need to happen inside the problem space. In fact, some of the most powerful ones don’t. Think of Julia Child, unfulfilled as a diplomat’s wife, who didn’t seek marriage counseling but enrolled in French cooking classes. Or Pierce Brosnan, faced with his wife’s cancer, who returned to painting. In both cases, the experiment seemed unrelated to the problem at hand, but not only did it help them cope, but it also reconnected them with their sense of agency.

Again, it might feel counterintuitive, but if the problem is too painful to touch directly, experimenting with something completely different can be more effective than pushing through. That’s because it bypasses resistance. By shifting your focus to a lower stake domain, your psychological defenses don’t get triggered. You’re not confronting the fear, you’re side-stepping it.

And this is where lateral experiments come in. Small tests in a completely different area of your life. They follow the exact same protocol, I will [action] for [duration], but with no attempt at solving the original issue. All you want to do here is try something new and observe what it opens up.

One woman I worked with had been trying to write to her estranged feather for over a year. But every time she sat down, she froze. The stakes were too high. So instead, she decided to experiment for something unrelated. She said, “I will attend one pottery class every Saturday for six weeks.”

On the surface, this had nothing to do with family. But pottery is messy. You start over, you get it wrong, you try again. And slowly her belief that everything had to be perfect started to loosen. She discovered she was someone who could tolerate messiness, and even embrace it. Until one day, she finally wrote that letter to her father.

Someone else was stuck in a job that wasn’t right, but couldn’t get himself to leave. Every attempt to plan an exit led to more paralysis. He was thinking, what about the money? What will my family think? So instead, he experimented with something uncomfortable. He said: “I will swim in cold water every morning for 10 days.”

Turns out, he could handle it. This experiment was all about discomfort. Physical immediate chosen discomfort. And the cold water revealed someone who could choose that discomfort, someone braver than the person stuck in that job. And so two weeks later, he resigned.

As you can see, these experiments weren’t aimed at solving the original problem. They were aimed at changing the conditions around it, at creating an environment where something new could emerge, at creating space for a surprising insight. And this is really what makes them so powerful.

By experimenting in this way, you interrupt the story you’re stuck in, and you let a new story start to form. You surprise yourself not because you tried to change, but because you stepped outside of the frame that was keeping you stuck. And when you surprise yourself, you create a new insight which can become a new story about who you are.

Writing your own story and keeping that story alive, this is really what living an experimental life is all about. Every experiment brings you closer to becoming you. And this is how you become the fullest, freest version of yourself. Not through self-improvement, but through self-discovery.

Tiny experiments help you release control. They teach you that you can act without knowing the outcome, that you can learn from uncertainty instead of being paralyzed by it. They teach you that curiosity is the key and that every time you loosen your grip, you let life become your laboratory.

At a deeper level, they expand your sense of self. Every time you act outside of your usual patterns, you discover parts of yourself that were hidden or stuck. Parts of yourself you didn’t even know were there.

Whether you decide to experiment directly or laterally, the result is the same. You stop trying to control who you think you should be, who you’ve trained yourself to be, and you start uncovering who you already are.

So now, here’s my invitation for you. Design one tiny experiment that you can start this week. Not next week, not after you’ve planned it perfectly. Think of an area where you feel stuck, and then use the protocol that I shared with you: I will [action] for [duration].

If the problem is too painful, too overwhelming, too charged to approach directly, then forget about that problem completely. Don’t try to be strategic. Pick something completely unrelated. Something where the stakes are low but your curiosity is high. Something creative, playful, physical, maybe a little bit uncomfortable. Something that has nothing to do with solving the problem at hand and everything to do with discovering who you are.

Know that the path to discovering yourself isn’t straight. Sometimes you have to go to pottery classes to write a difficult letter. Sometimes you have to swim in cold water to quit the wrong job. But with practice, whenever you feel stuck, you won’t panic about losing control. You’ll take a breath. Maybe you’ll smile. And you’ll ask: “What tiny experiment could I try?” Because you’ll know, you’ll truly know, that control keeps you small but curiosity sets you free. Thank you. [Applause]

The post How tiny experiments can set you free | Anne-Laure Le Cunff | TEDxNashville | Transcript appeared first on Ness Labs.

2026-01-15 18:24:17

When we’re stuck creatively, productively or intellectually, we often tend to frame the problem as a lack of ideas, discipline, or motivation. So we try to push, to think harder, or to optimize our tools and systems.

But “stuckness” is rarely a thinking problem. It’s a nervous system state, which can be regulated much more efficiently through the body than through effortful thought.

Cognition doesn’t operate in isolation. It’s continuously shaped by signals from the body, whether that’s your posture, movement, breathing, muscle tension, or other sensory input. These signals all modulate arousal, attention, and threat perception before conscious thought even begins.

This is why small physiological changes can have surprisingly large cognitive effects. A slight change in breathing pace, a brief bout of movement, or a shift in posture can alter how clearly you think and how flexible your cognition is.

Somatic regulation is the practice of using your body to change cognitive and emotional states instead of relying on top-down thinking alone.

You may have heard the term somatic healing. Somatic regulation uses similar tools, but with a different orientation:

| Somatic Healing | Somatic Regulation |

| Past-focused | Present-focused |

| Release | Momentum |

| Long protocols | Tiny experiments |

Somatic regulation treats bodily signals as useful inputs, creating the conditions for movement – mental movement included.

There are many ways to feel stuck. Rumination, avoidance, and perfectionism… These loops tend to persist because there’s a mismatch between what the task requires and your current physiological state. Change the state, and the loop often loosens on its own.

Here are three ways to get unstuck, depending on the kind of “stuckness” you’re experiencing:

1) Creatively stuck. Creative work benefits from variability. Changing posture – such as sitting to standing, collapsed to upright – or changing location can be enough to introduce new sensory input. A short walk outside without additional stimulation (no phone, no podcast) can also help when you feel creatively stuck.

2) Productively stuck. Difficulties with being productive often reflect an arousal mismatch: your energy may be too low or too high for the task. Brief, gentle movement such as stretching, swaying, or light dancing can help bring your arousal level into a workable range. So get up from your desk, put your favorite song on, dance like no one’s watching, and then only get back to work!

3) Intellectually stuck. Deep thinking relies on working memory and a sense of safety to give the task your full attention, both of which degrade under stress. Slowing the breath slightly, especially by lengthening the exhale, can help reduce stress and give your nervous system a cue of safety before returning to the problem you’re trying to solve.

After the state shift, reflect to notice patterns. What kind of stuckness was this? What changed after adjusting the state?

This simple metacognitive practice doesn’t have to take a lot of time. One or two sentences in your journal or note-taking app.

Over time, these field notes will become a personal map of how different states interact with different kinds of work and tasks.

Getting unstuck is rarely about better ideas or stronger discipline. It’s about restoring movement – first physical, then emotional and cognitive. When you feel stuck, start below the neck. Change the state first.

The post How to Get Unstuck: Simple Somatic Regulation Practices appeared first on Ness Labs.

2026-01-08 17:55:17

Most advice about consistency sounds the same: try harder, be more disciplined, push through resistance. Discipline is often seen as the difference between people who succeed and people who don’t. And if you fall off, the explanation is usually moralized: not enough willpower, lack of grit, laziness.

But people don’t fail because they don’t try hard enough. They fail because the system they’re operating in makes sustained effort too costly.

From a scientific perspective, discipline is the ability to apply self-control to override impulses in service of longer-term goals.

Decades of research suggest that self-control does predict positive outcomes. But it also shows something more subtle: self-control works best when it’s used sparingly. When people rely on constant “effortful inhibition” (forcing themselves to act) their performance degrades over time.

That’s because this kind of effortful inhibition activates brain networks that are metabolically expensive and sensitive to stress and fatigue.

Instead, research finds that people who appear highly disciplined are not constantly exerting more willpower. Rather, they tend to rely on habits, routines, rituals to maintain their wellbeing, and ways to design their environment that reduce the need for active control.

This is where devotion becomes a more useful tool than discipline. Etymologically, devotion comes from the Latin devovēre: to dedicate by a vow, to promise solemnly. Devotion implies commitment rooted in meaning and identity rather than forceful compliance with a rule.

When you’re devoted to an action, you don’t force yourself to act; the action expresses something you value.

Instead of effortful inihibition, this maps onto what researchers call “harmonious passion” – engagement that is freely chosen and integrated into your identity. Harmonious passion has been linked to greater persistence, better well-being, and being more likely to get in the flow.

You’ve probably noticed that caring deeply about something doesn’t guarantee that you can act on it consistently. That’s because devotion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and its impact depends heavily on friction – the total resistance between intention and action.

Friction can come from your environment, from a lack of skills or routines, or from the activation energy required to get started.

Two people can be equally devoted and have radically different outcomes because one is operating in a low-friction system and the other in a high-friction one.

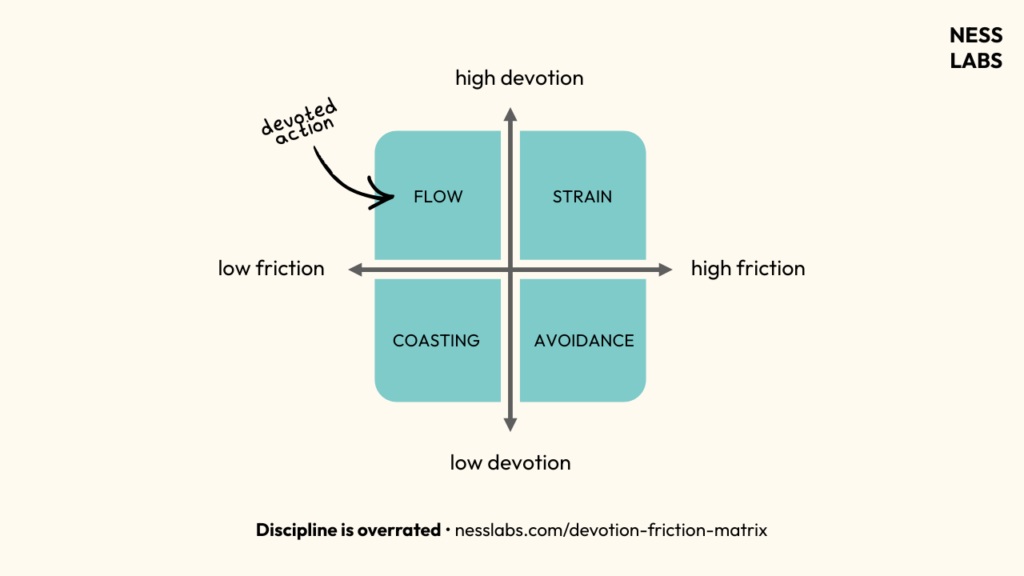

The Devotion-Friction Matrix of devoted action has four states:

There’s no point optimizing for maximal devotion or minimal friction in isolation. To get in the flow, you need to optimize for devoted action, where what you care about deeply is also easy enough to do repeatedly.

Here are three evidence-backed ways to do that:

1. Lower your activation energy. You might care a lot about working out or writing, but find yourself procrastinating. When that happens, stop focusing on finishing and focus on starting instead. For example, don’t say you’ll do a work out. Just put on your running shoes and step outside. Don’t say you’ll write the piece. Just open the document and write one sentence.

2. Design your environment. Make the desired action the default and the distractions slightly inconvenient. For instance, eave your book on your pillow and charge your phone in another room, or make unhealthy ones high-friction by putting them out of reach.

3. Run tiny experiments: Turn curiosity itself into an act of devotion. Pick one action to test for a specific duration, playing with variables such as timing, location or accountability, then observe what reduces effort and increases intrinsic reward.

If you want to show up reliably, don’t ask how to force yourself to work harder. Ask what you’re devoted to and what unnecessary friction is standing in the way. This way, consistency becomes a property of the system itself.

The post Discipline is Overrated: The Devotion–Friction Matrix appeared first on Ness Labs.

2025-12-18 21:42:32

This year hit me like a bulldozer. There was no amount of reading and research that could have prepared me for this level of intensity, and I want to start this annual review by saying thank you.

I’m grateful to my body and brain for mostly holding up. I’m grateful I have access to spaces and tools such as psychedelic medicine, ecstatic dance, and entrepreneur retreats that have helped support my mental health throughout this journey.

Most of all, I’m grateful to the people in my life – my family, friends, colleagues, and the entire Ness Labs community – who all showed up in wonderful ways this year.

So much happened, but here’s a quick bullet-point overview before I dive in:

I consider myself a child of the internet. As a teenager, I had a hand-coded blog and a community of online friends from all over the world, whom I’d only ever communicated with in writing via phpBB forums and our ‘blogring’ (remember those?).

Although I had a bunch of odd jobs when I was younger, my first ‘real’ job was at Google, and Ness Labs is largely an online business – with an online newsletter, online community, and online courses.

So I thought I was prepared for the influx of online attention I’d get when launching the book. Boy, was I wrong.

Going on dozens of podcasts was not only exhausting at times, but getting featured on big YouTube channels meant millions of people heard from me for the first time – and not all of them were nice. When the book came out in March, I really struggled with the rare but still hurtful comments on my accent, my appearance, and my supposed unchecked privilege.

I didn’t have to deal with Tim Ferriss levels of threats, but to give you an idea, some commenters said my accent made their ears bleed, that I must be funded by my parents, and that I should go back to my country. I knew I shouldn’t care, but I did, and it took a couple of months to build a digital immune system.

In general, my physical and mental health wasn’t great during the launch. Being in the US meant I didn’t have my healthy routines, including my favorite snacks, familiar local walks, and coffee catch-ups with close friends. I did go to ecstatic dance a couple of times in New York and Austin, but it wasn’t the same as having my regular practice in London.

All the traveling also meant I cancelled meaningful annual rituals. Each year, we organize a psilocybin ceremony with my best friends; that didn’t happen (but I did get to organize one for my family). I spent part of my teenage years with a foster family and normally visit my second mom once a year; that also didn’t happen.

I gained weight, my sleep was all over the place, and I even skipped many days of daily journaling – something I hadn’t done in years.

Part of me felt guilty about promoting a book that includes an entire chapter on mindful productivity when clearly I still had lots to learn myself. But I was also incredibly grateful for the tools and mindset I’d developed that kept me from completely burning out, even if this pace wasn’t sustainable long-term.

Then, in July, when I had planned to take a much-needed break, I discovered that the French translation of Tiny Experiments was so bad that I couldn’t bear the idea of putting my name on it. So I ended up spending the entire month translating my own book into French. This didn’t help with my mental health, but it gave me deep appreciation for the craft of a translator.

Fortunately, just when you’re stuck in a rut, life has a way of jolting you awake – even if it’s not how you’d choose to be woken up.

This year, my mom turned 70, and for her birthday she asked that we all go back to Burning Man as a family so they could renew their wedding vows. This was a magical week. Not just the serendipitous encounters, the heart-opening conversations, the art and the music, but having my phone off for an entire week, with no sense of time, waking up and going to bed when my body wanted to, eating when I was hungry and not as a way to cope with stress, and walking, cycling, dancing every day – it healed me deeply.

That is, until the last day, when my dad collapsed in my arms and had to be rushed via helicopter to the hospital in Reno, where he was unconscious for the longest 48 hours of my life.

I wrote about it elsewhere so I won’t repeat it here, but this terrifying experience had the effect of reconnecting me with what truly matters: to share the precious little time we have on this earth with the people we love, to connect with other human beings on this messy journey that is life, and to be as present as possible for each of those beautiful, challenging, magical moments.

The second half of the year was a slow process of rebuilding, reprioritizing, recentering. I decided to let go of two members of the extended Ness Labs team and to invest more in the growth of core team members. We agreed on shared mental models to drive our day-to-day business decisions and built new systems to support these.

In the spirit of learning in public, I also decided to publicly embrace the messiness of the process, letting go of my fear that people wouldn’t trust my expertise if I looked like I was still figuring it out.

When I froze on stage during my TEDx talk in front of 800 people, I decided to share that experience instead of hiding it in shame. The post went somewhat viral and resulted in many new people discovering my work. I also shared screenshots of some of the rude comments and emails I received instead of processing them on my own.

I think this vulnerability played a big part in the growth of the Ness Labs community this year by attracting like-minded people who want to live more openly, honestly, and kindheartedly. Tiny Experiments sold more than 60,000 copies in its first six months, and my Instagram account grew from 3,000 to more than 50,000 followers in the past twelve months.

And ultimately, the kind and constructive messages from people of all ages and backgrounds around the world vastly outnumbered the hurtful ones.

I write an annual review every single year because looking back helps me move forward. Reflecting on 2025, I see several themes I’d like to keep exploring and trends I’d like to shift.

Professional life – I couldn’t have hoped for more success in this area, but a lot of it was built on sheer effort and willpower, which aren’t sustainable. Moving forward, I’d like to keep building systems with my team and say no more often so I can focus on the projects that can truly have a meaningful impact.

Intellectual life – While I did manage to produce research, my academic work felt very output-oriented: data collection tasks, grant proposals, ethics applications. In 2026, I want more space for reading and thinking. I know how it might sound after the year I’ve had, but I’m also starting to outline my next book, which shows me that I truly love writing (or that I might be a bit crazy, or both).

Spiritual and personal life – Rituals and time in community are crucial to maintaining my physical and mental health. I want to build my life around those foundations, with work fitting around them rather than the other way around.

Lastly, this year made me even more grateful for the amazing people in my life. I’ve been terrible at staying in touch – my WhatsApp is an absolute mess and I’ve been slow to respond or completely missing messages. Thankfully, my friends are wonderful and nobody resented me for not being a great friend this year. If you’re someone I haven’t replied to, please follow up with me; that would be the best holiday gift

Thank you for reading, and happy new year!

The post 2025 Year in Review: Presence versus Performance appeared first on Ness Labs.