2026-02-27 17:21:52

I kind of want to write about AI every day these days, but I’ve got to pace myself so you all don’t get overloaded. So here’s a roundup post with only one entry about AI. Just one, I promise!

Well, OK, there’s also a podcast episode about AI. I went on the truly excellent Justified Posteriors podcast to talk about the economics of AI with Andrey Fradkin and Seth Benzell. It was truly a joy to do a podcast with people who know economics at a deep level!

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup.

Erik Brynjolfsson believes that AI caused a productivity boom last year:

Data released this week offers a striking corrective to the narrative that AI has yet to have an impact on the US economy as a whole…[N]ew figures reveal that total payroll growth [in 2025] was revised downward by approximately 403,000 jobs. Crucially, this downward revision occurred while real GDP remained robust, including a 3.7 per cent growth rate in the fourth quarter. This decoupling — maintaining high output with significantly lower labour input — is the hallmark of productivity growth…My own updated analysis suggests a US productivity increase of roughly 2.7 per cent for 2025. This is a near doubling from the sluggish 1.4 per cent annual average that characterised the past decade…

Micro-level evidence further supports this structural shift. In our work on the employment effects of AI last year, Bharat Chandar, Ruyu Chen and I identified a cooling in entry-level hiring within AI-exposed sectors, where recruitment for junior roles declined by roughly 16 per cent while those who used AI to augment skills saw growing employment. This suggests companies are beginning to use AI for some codified, entry-level tasks.

But Martha Gimbel says not so fast:

There are three reasons why what we are seeing may not actually be a real jump in productivity—or an irreconcilable gap between economic growth and job growth…

First, productivity is noisy data…We shouldn’t overreact to one or even two quarters of data. Looking over several quarters, we can see that productivity growth has averaged about 2.2%. That is strong, but not unusually so…

Second…for GDP growth in 2025, we’re still waiting for [revisions to come in]. Note that any comparison of jobs data and GDP data for 2025 is comparing revised jobs data to unrevised and incomplete GDP data…

Third…GDP data has been weird in 2025 partly because of policy and behavioral swings around trade. If you look at job growth relative to private-domestic final purchases…[job growth] is still low, but not as low as it is relative to the GDP data…

[E]ven if you trust the productivity data…there are other explanations besides AI…One reason job growth in 2025 was so low was because of changes in immigration policy. If the people being removed from the labor force were lower productivity workers, that will show up as an increase in productivity even though the productivity of the workers who remain behind has not changed…

Second, if you look at the productivity data, it appears that much of the boost is coming from capital utilization due to increased productive investment…[A]t this point it is people investing in AI not people becoming more productive by using AI.

Meanwhile, in January, Alex Imas had a very good post about AI and productivity:

Alex gathers a bunch of studies showing that AI improves productivity in most tasks. But in the real world, productivity improvements from new technology famously come with a lag, as companies retool their business models around the new tech. For a while, productivity actually falls, then starts to rise once the new business models start working. This is called the productivity J-curve. Brynjolfsson thinks we’ve hit the rising part of the J-curve, but Alex thinks we haven’t:

At the macro level, these [micro] gains [from AI] have not yet convincingly shown up in aggregate productivity statistics. While some studies show a slow down in hiring for AI-exposed jobs—which suggests that individual workers are either becoming more productive or tasks are being automated—the extent and timing of these dynamics are currently being debated. Other studies have found no changes in hours worked or wages earned based on AI use.

Also, Brynjolfsson thinks that job loss in AI-exposed occupations is a sign of growing productivity. But that may not be the case; new technologies can grow productivity while increasing hiring, by creating new tasks for humans to do. A new survey by Yotzov et al. finds that although corporate executives in the U.S., Australia, and Germany expect AI to cut employment, employees themselves expect it to provide new job opportunities:

We survey almost 6000 CFOs, CEOs and executives from stratified firm samples across the US, UK, Germany and Australia…[A]round 70% of firms actively use AI…[F]irms report little impact of AI over the last 3 years, with over 80% of firms reporting no impact on either employment or productivity…[F]irms predict sizable impacts over the next 3 years, forecasting AI will boost productivity by 1.4%, increase output by 0.8% and cut employment by 0.7%. We also survey individual employees who predict a 0.5% increase in employment in the next 3 years as a result of AI. This contrast implies a sizable gap in expectations, with senior executives predicting reductions in employment from AI and employees predicting net job creation.

And a new study by Aldasoro et al. finds that in Europe, AI adoption seems to be increasing employment at the companies that adopt it:

Our results reveal three key findings. First, AI adoption causally increases labour productivity levels by 4% on average in the EU. This effect is statistically robust and economically meaningful…[T]he 4% gain suggests that AI acts in the short term as a complementary input that enhances efficiency…

Second, and crucially, we find no evidence that AI reduces employment in the short run. While naïve comparisons suggest AI-adopting firms employ more workers, this relationship disappears once we account for selection effects through our instrumental variable approach. The absence of negative employment effects, combined with significant productivity gains, points to a specific mechanism: capital deepening. AI augments worker output – enabling employees to complete tasks faster and make better decisions – without displacing labour. [emphasis mine]

Everyone seems to just assume that AI is a human-remover, and in some cases it is. But overall, it might actually turn out to be complementary to humans, like previous waves of technology; we just don’t know yet. The lesson here is that we don’t really know how technology affects productivity, growth, employment, etc. until we try it and see. The economy is a complex machine that reallocates a lot of stuff in very surprising ways.

So stay tuned…

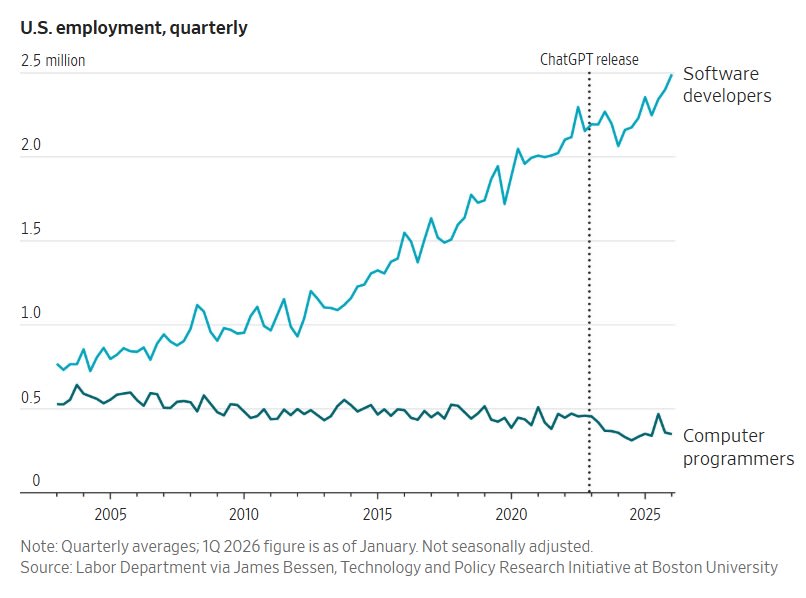

Update: Here is a good chart from the excellent Greg Ip of the Wall Street Journal:

Also, for what it’s worth, here’s Goldman Sachs:

One of the most fun posts I’ve ever written was about how building high-end housing can reduce rents for lower-income people. I called it “Yuppie Fishtank Theory”:

The basic idea is very simple: If you build nice shiny new places for high earners (“yuppies”), they won’t go try to take over the existing lower-cost housing stock and muscle out the working class.

This is important because a lot of people believe the exact opposite. They think that if you build new market-rate (“luxury”) housing in an area, it’ll attract rich people, cause gentrification, and raise rents.

Over the years, my theory has been proven right — and the “gentrification” theory has been proven wrong — again and again. Here was a roundup I did of the evidence back in 2024:

Now Henry Grabar flags some new evidence that says — surprise, surprise — that Yuppie Fishtank Theory is still true:

A new study lays out exactly how a brand-new building can open up more housing in other, lower-income areas, creating the conditions that enable prices to fall…

In the paper, three researchers looked in extraordinary detail at the effects of a new 43-story condo project in Honolulu…What the researchers found was that the new housing freed up older, cheaper apartments, which, in turn, became occupied by people leaving behind still-cheaper homes elsewhere in the city, and so on…The paper estimates the tower’s 512 units created at least 557 vacancies across the city—with some units…creating as many as four vacancies around town…

To figure this out, the researchers…traced buyers arriving at the new apartments back to their previous homes and then, in some cases, they traced the new occupants of those homes back to prior addresses. The study found that the Central’s new residents left behind houses and apartments that were, on average, 38 percent cheaper, per square foot, than the apartments they moved into.

Yuppie Fishtanks win again!

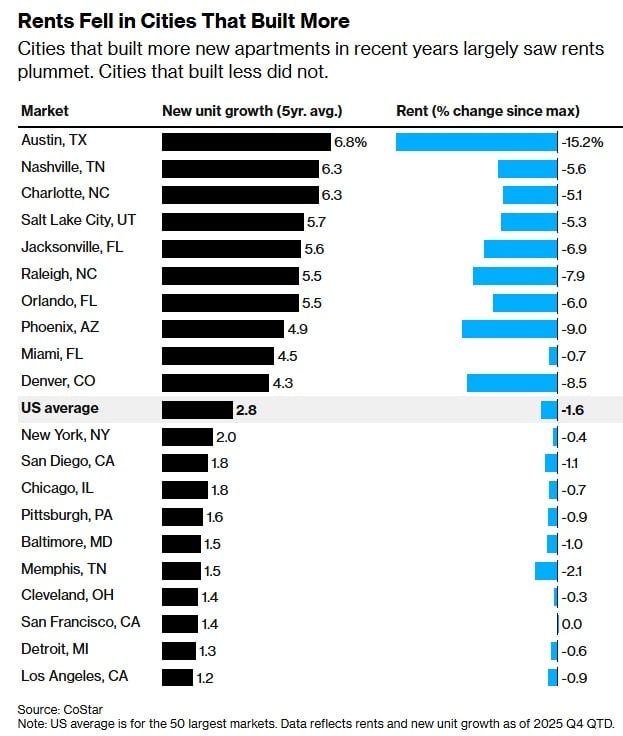

Cities that are applying Yuppie Fishtank Theory are seeing their rents fall. Here’s a Bloomberg story from December:

Rents got cheaper in several major cities this past year, thanks to an influx of luxury apartment buildings opening their doors and luring tenants to vacate their old homes…New building openings are bringing rents down as wealthy tenants trade up, forcing landlords to drop prices for older apartments. Rents for older units have fallen as much as 11%, and some are now on offer at rates as low as homes that are usually designated as “affordable”…The changed dynamic in the rental market is challenging the idea that luxury housing doesn’t help the broader ecosystem.

Overall, cities that build more housing are seeing lower rents:

At this point, “building housing reduces rent” is as close to a scientific law of the housing market as we’re likely to find.

Build more housing!!

Three years ago, David Oks and Henry Williams wrote a long post claiming that economic development was dead — that poor countries had done great in the post-WW2 decades when they sold raw materials to fast-growing rich countries, but that their growth in the 90s, 00s, and 10s was a bust. That was nonsense, and I wrote a lengthy rebuttal here:

Instead of rehashing that debate, I just want to link to Oks’ latest post, in which he expresses extreme pessimism about global poverty:

He cites a recent post by Max Roser of Our World in Data (the excellent site where I get many of the charts for this blog). Roser notes that extreme poverty — defined as the fraction of people living on less than $3 a day — has declined so much in South Asia, East Asia, and Latin America that it has basically vanished. This leaves Africa as the only region with an appreciable number of extremely poor people left (except for some parts of Central Asia). And since African poverty rates are not declining, and African population is growing much faster than population elsewhere, this means that the number of extremely poor people in the world is set to start rising again:

The first thing to note is that by using this chart, and by making this argument, David Oks directly contradicts his thesis from his 2023 article. In 2023, Oks argued that global development since 1990 had been disappointing; in his new post, Oks argues that poverty reduction in 1990-2024 everywhere outside of Africa was so incredibly successful that it basically went to completion and has nowhere left to go!

Oks’ old post was pessimistic about the entire developing world — South Asia, Latin America, Africa, and so on. In this new post, he retreats to pessimism about Africa alone. This is a significant retreat — it’s an implicit acknowledgement that development was very very real for the billions of poor people who lived outside Africa in 1990.

As for whether Oks is right about Africa, only time will tell. But note that the rising global poverty in the chart above is entirely a forecast. If African growth surprises on the upside — say, from solar power and AI — and African fertility falls faster than expected, then we could see Africa follow in the footsteps of the other regions.

Our goal should be to keep the pessimists embarrassed.

On paper, the U.S. is a lot richer than most other rich countries — including Canada:

In terms of per capita GDP, Canada is poorer than Alabama, America’s poorest state. Canada is a little less unequal than America, so the difference in median incomes between the two countries is smaller — only about 18% higher as of 2021 (though the gap is growing). But that’s still a sizeable gap!

Europeans, Australians, and Canadians who visit America’s disorderly and crime-ridden city centers can sometimes balk at this fact. They instinctively start groping for some reason the numbers must be wrong. But reporters from Canada’s Globe and Mail traveled to Alabama, and discovered that the numbers don’t lie — America really is just a very, very rich place, even compared to other countries. Here are some excerpts from their article:

For eons, Canadians have viewed Alabama as a small state that, save for a few pockets, is dirt poor…For an ego check, The Globe and Mail travelled to the Deep South to understand how this happened. Immediately, it was obvious Alabama is misunderstood. In Huntsville, there are as many Subaru Outbacks as there are pickup trucks, and the geography in Alabama’s two largest metropolitan areas – Birmingham and Huntsville – looks nothing like the historical imagery…

Alabama is also home to five million people…and its economy is booming. The state’s unemployment rate is now just 2.7 per cent, versus 6.5 per cent in Canada, and its major employers include Airbus SE and giant defence contractor Northrop Grumman Corp. The state has also morphed into an auto manufacturing powerhouse with plants from Mercedes-Benz AG, Toyota Motor Corp., Hyundai Motor Co. and more. In 2024, Alabama made nearly as many vehicles as Ontario…

As for Birmingham itself, there’s the beauty of the rolling hills, which deliver stunning fall foliage. And the city’s becoming a foodie hub. A new restaurant, Bayonet, was named one of America’s 50 best restaurants by The New York Times last fall. And despite the bible thumping, Birmingham has a sizable LGBTQ+ community and scored the same as Boston on the Human Rights Campaign’s Municipal Equality Index.

The Globe and Mail article notes that Alabama has a higher poverty rate and lower life expectancy than Canada — and being a newspaper in a progressive country, it fails to mention the much higher crime rate. But the fact is, for most Alabamans, the material standard of living is more comfortable than what prevails in much of Canada.

People who believe America’s wealth is fake need to go there and see for themselves that it’s real.

In general, economists find that immigration’s economic effect on the native born is either positive or zero. But one famous economist, George Borjas, consistently finds negative effects. This makes Borjas beloved of the Trump administration and the nativist movement in general — it’s very common to hear MAGA people cite Borjas in debates.

It’s very odd that one economist keeps getting results about immigration that are so out of whack with what everyone else finds. Well, it turns out that if you look closely at George Borjas’ methodologies, you find a lot of dodgy stuff. I wrote about this several times back during the first Trump administration, when I worked for Bloomberg. Here’s what I wrote in 2015:

[I]n 2015, George Borjas…came out with a shocking claim -- the celebrated [David] Card result [about the Mariel Boatlift not harming American workers], he declared, was completely wrong. Borjas chose a different set of comparison [cities]…He also focused on a very specific subset of low-skilled Miami workers. Unlike Card, Borjas found that the Mariel boatlift immigration surge had a big negative effect on native wages for this vulnerable subgroup.

Now, in relatively short order, Borjas’ startling claim has been effectively debunked. Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov, in a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper…find that Borjas only got the result that he did by choosing a very narrow, specific set of Miami workers. Borjas ignores young workers and non-Cuban Hispanics -- two groups of workers who should have been among the most affected by competition from the Mariel immigrants. When these workers are added back in, the negative impact that Borjas finds disappears.

But it gets worse. Borjas was so careful in choosing his arbitrary comparison group that his sample of Miami workers was extremely tiny -- only 17 to 25 workers in total. That is way too small of a sample size to draw reliable conclusions. Peri and Yasenov find that when the sample is expanded from this tiny group, the supposed negative effect of immigration vanishes.

All of this leaves Borjas’ result looking very fishy.

And here was a follow-up in 2017:

Recently, Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development and Jennifer Hunt of Rutgers University found an even bigger problem with Borjas’ study. Clemens and Hunt noted that in 1980, the same year as the Mariel boatlift, the U.S. Census Bureau changed its methods for counting black men with low levels of education. The workers that Borjas finds were hurt by the Mariel immigration include these black men. But because these workers generally have lower wages than those the Census had counted before, Borjas’ finding of a wage drop among this group, the authors claim, was almost certainly a result of the change in measurement.

And here’s what I wrote in 2016:

Borjas has written a book…called “Immigration Economics.”…However, University of California-Berkeley professor David Card and University of California-Davis’ Peri have written a paper critiquing the methods in Borjas’ book. It turns out that the way Borjas and the economists he cites do immigration economics is very, very different from the way other researchers do it.

One big difference is how economists measure the number of immigrants coming into a particular labor market…[I]nstead of using the change in the number of immigrants, Borjas just uses the number of immigrants itself…This creates a number of problems.

Let’s think about a simple example. Suppose there are 90 native-born landscapers in the city of Cleveland, and 10 immigrant landscapers. Suppose that demand for landscapers goes up, because people in Cleveland start buying houses with bigger lawns. That pushes up the wages of landscapers, which will draws 100 more native-born Clevelanders into the landscaping business. But the supply of immigrants is relatively fixed. So the percent of immigrants in the Cleveland landscaping business has gone down, from 10 percent to only 5 percent, even though the number of immigrants in the business has stayed the same.

Borjas will find that the percent of immigrants in the business goes down just as wages go up. But to conclude that native workers’ wages went up because immigration went down would be totally incorrect, because immigration didn’t actually fall! In fact, Borjas’ method is vulnerable to reaching exactly this sort of erroneous conclusion. Card and Peri point out that if you use the more sensible measure, there’s not much correlation between immigrant inflows and native-born workers’ wages and income mobility.

In other words, there’s a clear pattern of Borjas using strange and seemingly inferior methods, and arriving at conclusions that diverge radically from his peers. So I was not exactly surprised when Jiaxin He and Adam Ozimek looked at Borjas’ recent work on H-1B workers also contained some very dodgy methodology:

Borjas’s February 2026 working paper attempted to answer whether H-1B workers earn less than comparable native-born workers by combining data on actual H-1B earnings with American Community Survey data on native workers. The conclusions are negative, with H-1B holders earning 16 percent less. But these findings result from substantial data errors.

…The most significant mistake is a crucial temporal mismatch between his H-1B and native-born samples: the H-1B applications span 2020-2023, while the ACS data covers just 2023.

Nowhere did the paper mention controlling for inflation or wage growth. Given 15.1 percent inflation and an 18.7 percent wage increase for software occupations alonefrom 2020 to 2023, comparing wages of H-1B workers from 2020 to 2023 to… native-born wages from 2023 only produces negatively biased results that overstates the wage gap…A simple approach is to directly compare the 2023 H-1B observations (FY 2024) to 2023 ACS data. Alternatively, we can use all years but adjust for inflation and convert all years to real 2023 dollars. Both approaches cut the wage gap roughly in half…

The second error stems from controlling for geographic wage drivers using each worker’s PUMA (public use microdata area)…The problem is that Dr. Borjas uses the PUMA where visa holders work alongside the PUMA where native workers live. Consider a native-born software developer working at Google in Mountain View who resides in a cheaper area like Fremont. If residential areas have lower average wages than business districts, this mismatch systematically inflates the apparent native wage and negatively biases the H-1B wage gap.

Another Borjas paper with serious methodological errors, and an anti-immigration conclusion that disappears when you correct the errors? Shocking!

By this point, it should be clear that whether these mistakes are intentional or not, Borjas’ anti-immigration conclusions tend to vanish when the mistakes are corrected. Borjas is not a good source of information on immigration topics; every time someone cites him in a debate, you know they haven’t looked seriously at the literature.

2026-02-26 15:06:54

I’ve been wanting to write this post for a while, actually. What triggered it was seeing this tweet:

Extreme tolerance of public disorder, and downplaying the importance of crime, is a hallmark of modern progressive American culture. There are plenty of Democrats who care about crime — Joe Biden recently tried to increase the number of police in America by a substantial amount — but there is constant pressure from the left against such measures. On social media, calls for greater public order are instantly met with accusations of racism and classism:

(And this was far from the most radical post on the topic.)

Nor is this attitude confined to anonymous radicals on social media. When Biden announced his Safer America Plan, the ACLU warned that putting more cops on the streets and punishing drug dealers would exacerbate racial disparities:

[I]n this moment of fear and concern, the president must not repeat yesterday’s mistakes today. He calls for hiring 100,000 additional state and local police officers – the same increase in officers as the 1994 crime bill. This failed strategy did not make America safer, instead it resulted in massive over-policing and rampant rights violations in our communities…And while it is important that the president’s plan commits to fixing the racist sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, it regrettably also perpetuates the war on drugs by calling for harsh new penalties for fentanyl offenses.

“While we are pleased with the president’s commitment to investing in communities, we strongly urge him not to repeat the grave errors of the 1990s — policies that exacerbated racial disparities, contributed to widespread police abuses, and created our current crisis of mass incarceration.

The ACLU is very wrong about policing and crime — there’s very solid evidence that having more cops around reduces the amount of crime, both by deterring criminals and by getting them off the streets.

In fact, the idea that tough-on-crime policies are racist is a pillar of progressive thought. It’s the thesis of Michelle Alexander’s influential 2012 book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which argues that mass incarceration is a form of racial segregation. Ta-Nehisi Coates, perhaps the most important progressive thinker of the 2010s, relentlessly attacked the “carceral state”.

A major progressive policy initiative, meanwhile, has been the election or appointment of district attorneys who take a more tolerant approach toward criminals. These “progressive prosecutors” really do prosecute crime less, although evidence of their impact on actual crime rates is mixed.

I am not going to claim that progressive attitudes are the reason America’s crime rate is much higher than crime rates in other countries. The U.S. has probably been more violent than countries in Asia and Europe throughout most of its history, and the divergence certainly long predates the rise of progressive ideology. It’s possible that the progressive prosecutor movement, the decarceration movement, and the depolicing movement exacerbated America’s crime problem a bit, but they didn’t create it.

What those progressive attitudes do do, I think, is to prevent us from talking about how important the crime problem is for the United States, and from coming up with serious efforts to solve it.

The thesis of this post is that when you compare America to other countries, what stands out as America’s most unique weakness is its very high crime rate — not just violent crime, but also public chaos and disorder. That statement might come as a shock to people who are used to hearing about very different American weaknesses.

For example, it’s common to hear people say that Europeans and Asians “have health care”, and that Americans don’t. That’s just fantasy. Around 92% of Americans, and 95% of American children, have health insurance, and those numbers keep going up.

Yes, U.S. health care is too expensive — we spend half again or double the fraction of GDP on health as many other countries, while achieving similarly good outcomes. That’s a real problem, and we should try to bring costs down. But this is tempered by the fact that Americans spend a lower percent of their health care costs out-of-pocket compared to people in most other rich countries:

And if you took health spending entirely out of the equation, Americans would still be richer than people in almost any other country. So our high health costs are more of a nuisance than a big difference in quality of life.

If not health care, what about health itself? America’s life expectancy has started to rise again, but it’s still 2 to 4 years less than other rich countries. The size of this gap tends to be overhyped — Germany’s life expectancy advantage over America is smaller than Japan’s advantage over Germany. And the difference is mostly due to America’s greater rates of obesity and drug/alcohol overdose — diseases of wealth and irresponsibility, rather than failures of policy.1 This stuff usually doesn’t affect quality of life unless you let it — if you don’t overeat, drink too much, do fentanyl, or kill yourself, your life expectancy in America is going to be similar to, or better than, people in other rich countries.

What about inequality and poverty? It’s true that America is more unequal than most other rich countries. About a quarter of Americans earn less than 60% of the median income, compared to around one-sixth or one-fifth in most other rich nations. But this is not because America is a uniquely stingy country where conservatives have managed to block government redistribution. In fact, the U.S. fiscal system — taxes and spending — is more progressive (i.e., more redistributionary) than that of most other rich countries, and we spend about as much of our GDP on social welfare as Canada, the Netherlands, or Australia. In fact, America’s system has become continuously more progressive over time.

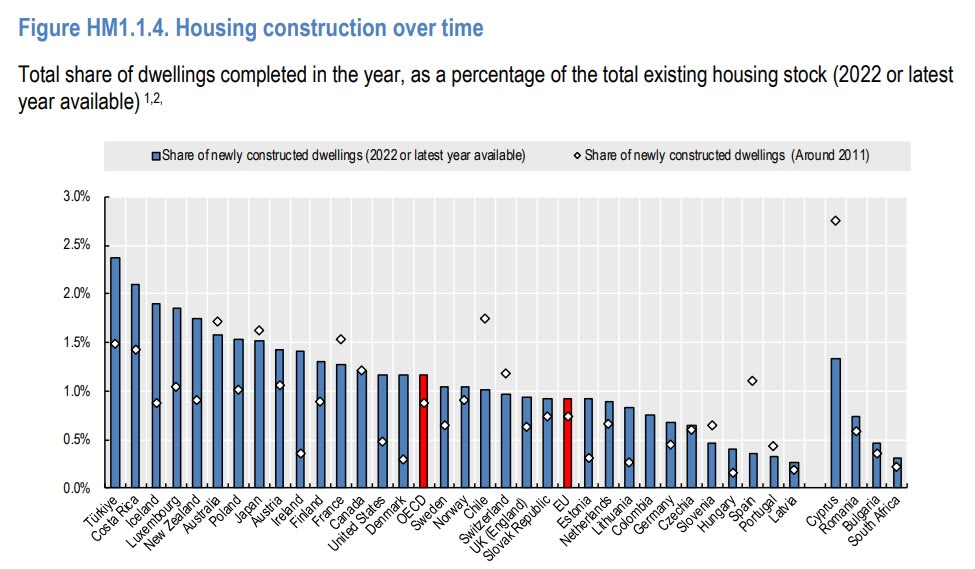

How about housing? You may have read the “Housing Theory of Everything”, which blames housing shortages for a variety of social and economic problems. It’s true that housing is very important, and that America doesn’t build enough of it. It’s also true that housing is a bit more expensive in America than elsewhere — according to the OECD, house prices relative to incomes are about 12% higher than in the average rich country. But U.S. houses are also much bigger than houses in most other countries, so it’s natural that they’d cost a little bit more. And America has actually been above average in terms of housing production in recent years, after lagging in the 2010s:

So it’s more accurate to say that housing is a big problem, but it’s a big problem all over the globe, not something that’s special to America.

How about transit and urbanism? Here, America is certainly an exception. The U.S. has the least developed train system in the developed world, and worse than many poor countries as well. America is famous for its far-flung car-centric suburbs, with their punishing commutes and paucity of walkable mixed-use areas. Only a few rich countries are more suburbanized than America, and those countries tend to have very good commuter rail service.

This is a real difference, though whether it’s good or bad depends on your point of view. Lots of people in America and elsewhere love suburbs and love cars. But I’m going to argue that to the extent that America’s urban development pattern is more suburbanized and more car-centric than people would like, it’s mainly due to crime.

So in almost all cases, the difference between America’s problems and other rich countries’ problems is minor. But when it comes to crime, the difference between the U.S. and other countries is like night and day.

The best way to compare crime rates across countries is to look at murder rates. Other crimes are a lot harder to compare, because A) reporting rates are very different, and B) definitions of crimes can differ across countries. But essentially every murder gets reported, and the definition is pretty universal and unambiguous. And although murder isn’t a perfect proxy for crime in general — you could have a country with a lot of theft but very few murders — it’s probably the crime that people are most afraid of.

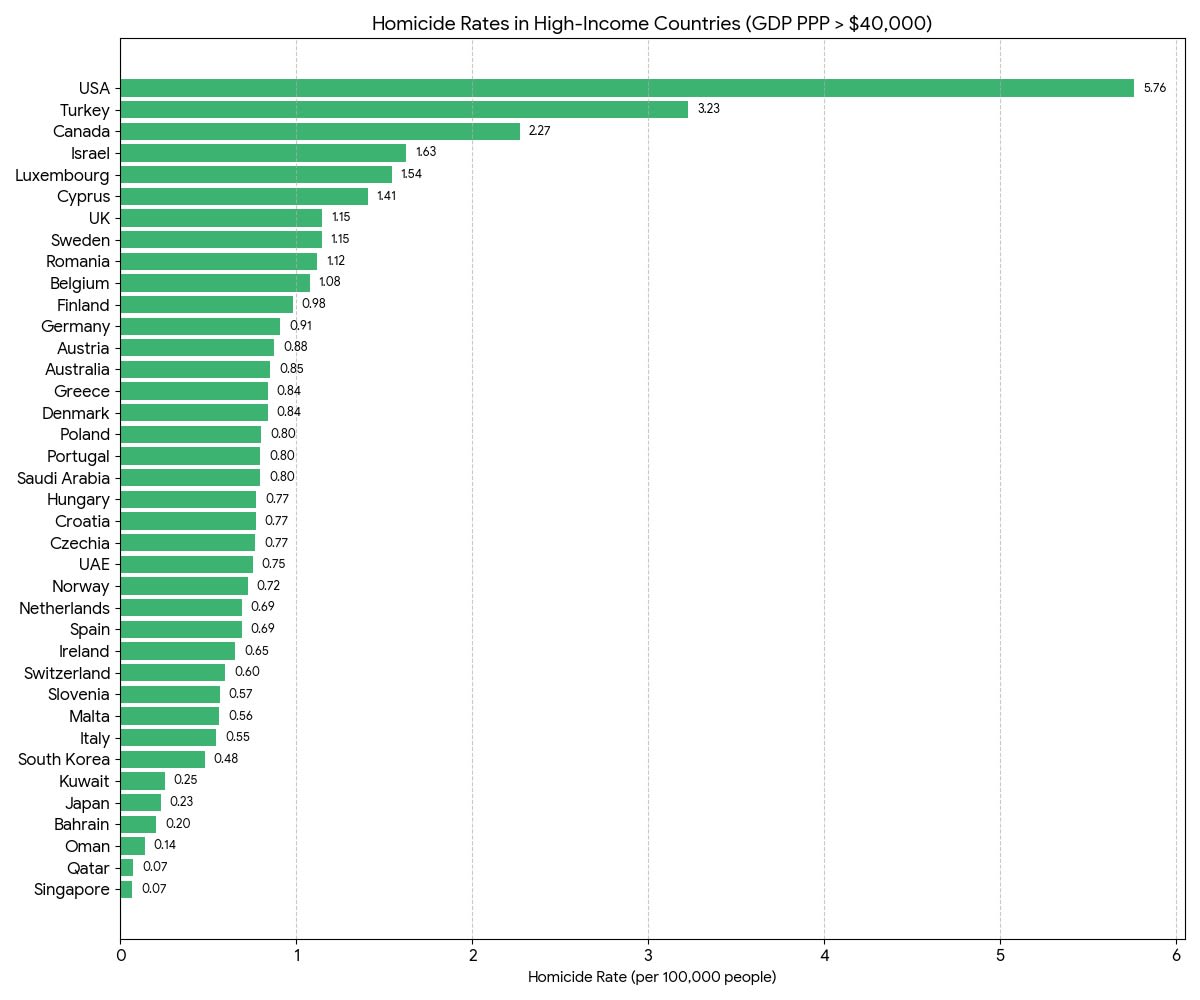

So when we look at the murder rate, we see that among rich countries,2 the United States stands out pretty starkly:

This is an astonishingly huge difference. America’s murder rate is between five and ten times as high as that of most rich countries.

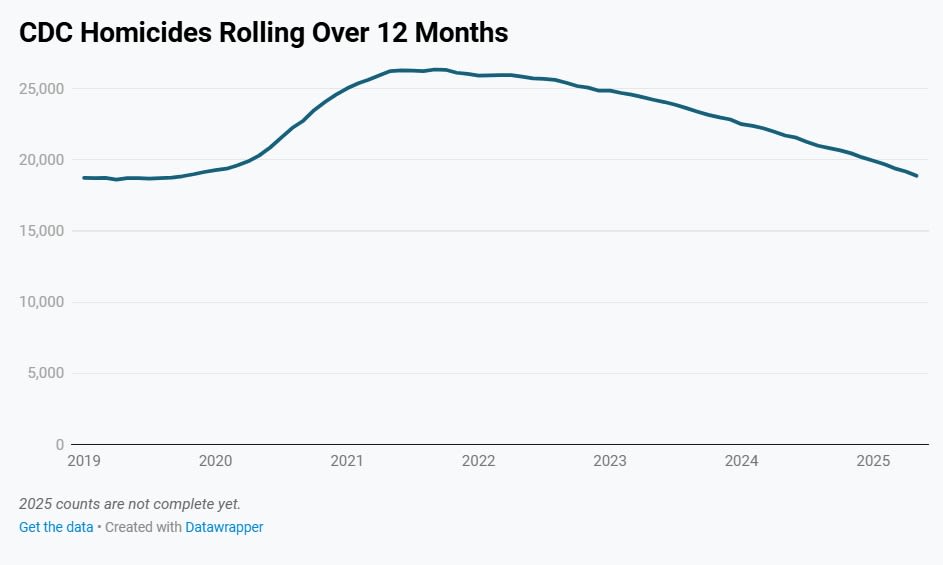

Many progressives will protest that violent crime has gone down in America since 2022. And in fact, murder really has gone down a lot.3 Here’s the CDC’s count of homicides:

But even after this decline, the U.S. homicide rate is still five to ten times higher than other rich countries! The recent improvement is welcome, but it hasn’t yet changed the basic situation.

Anyway, while murder is the most important crime, public order also makes a big difference. Here were some replies to the tweet about tolerating destructive behavior on American trains:

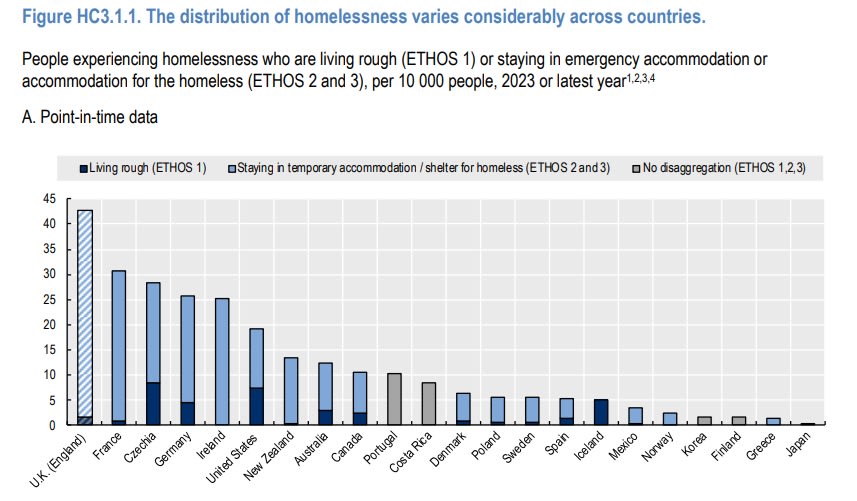

The tragic and disturbing scenes of mentally compromised people shouting, peeing, pooping, defacing property, and acting menacing in public — so familiar to residents of cities like San Francisco — are not entirely unique to America. I have been to a place in Vancouver that has similar scenes, and twenty years ago I even walked through a dirty and dangerous-seeming homeless camp in Japan. But overall, the differences between the countries are like night and day, and other countries seem to have made a concerted effort to bring order to their streets in recent years. The U.S., on the other hand, has seen a huge rise in the number of unsheltered homeless people in recent years:

And although America’s overall homelessness rate doesn’t stand out, it has a much higher unsheltered (“living rough”) population:

Obviously, unsheltered homelessness and public disorder aren’t the same thing — you can have lots of violent or threatening people on the streets who do have homes, and most homeless people are harmless. But homeless people do commit violent crime at much higher rates than other people, so when people walk down the street and see a bunch of seemingly homeless people, they’re not wrong to be scared.4

The ever-present threat of crime in U.S. cities has devastated American urbanism. In the mid 20th century, there was a huge exodus of population from the inner cities to the suburbs; this is often characterized as “white flight”, but middle-class black people fled the cities as well. Cullen and Levitt (1999) look at the effects of changes in the criminal justice system, and find that crime has been a big factor in Americans’ preference for suburban living:

Across a wide range of specifications and data sets, each reported city crime is associated with approximately a one-person decline in city residents. Almost all of the impact of crime on falling city population is due to increased out-migration…Households with high levels of education or with children present are most responsive to changes in crime rates…Instrumenting using measures of criminal justice system severity yields larger estimates than OLS, which suggests that rising city crime rates are causally linked to city depopulation.

It’s no surprise that America’s short-lived and minor urban revival in the late 1990s and 2000s followed a big decline in crime. But crime rates are still very high in the U.S., and Americans are still trying to move from the cities out to the suburbs and the far-flung exurbs.

Meanwhile, crime damages American urbanism in other ways. NIMBYs use the threat of crime to block affordable housing projects; this reduces housing supply, driving up prices everywhere, and making it difficult to build the multifamily apartment buildings that enable the kind of dense, mixed-use urbanism that prevails in Europe and Asia. The “housing theory of everything” is partially a story about crime.

Crime also makes it a lot harder to build good transit systems. Trains are a public space, and when there are violent, destructive, or menacing people on the train, it deters people from wanting to ride the train. There’s research showing this, but I also thought that a recent post by the blogger Cartoons Hate Her was especially vivid in explaining how the fear of disorder keeps women and parents away from transit:

When my daughter was a little over a year old, we were walking down the street in broad daylight (she was strapped to my chest and facing outward) when we heard a man about twenty feet away shout “I’M GOING TO FUCKING KILL YOU!”…[A]t least we had an easy safe option to escape…But if we had been on a subway, we would have had no easy choice. We could have waited for the train to stop and then switched cars—but what if he saw us leave and took that as a message, prompting the threat to move from “vaguely directed at my delusions” to “at the next person who triggers me?” What if we couldn’t get to the door in time? What if he followed us? What if he escalated before the train stopped?…

I’ve been told many times that people who are uncomfortable with this type of behavior need to just stay put, don’t make noise, and “avoid eye contact.” After all, asking someone to turn down their music could get you stabbed. You just need to keep your head down and you’ll be fine. That’s apparently all it takes, right? Except for Iryna Zarutska, who quietly sat down in front of a visibly deranged, pacing man on the bus, only to be stabbed to death shortly after. Or the young woman in the Chicago subway who was randomly lit on fire by a severely mentally ill subway rider? Or Michelle Go, the woman who was pushed in front of a subway to her death in New York City by a total stranger?…

Since 2009, assaults on public transit in New York City have tripled…Subway assaults also often involve strangers. When the attack is sexual, the victim is almost always a woman—and New York City alone accounts for around 4,000 sex crimes on public transit every year. These cases are likely underreported and limited to more severe crimes. Many women experience flashing, sexual harassment, groping, and public masturbation, and then never report it, assuming nothing would come of the report. (And honestly? They’re correct.)

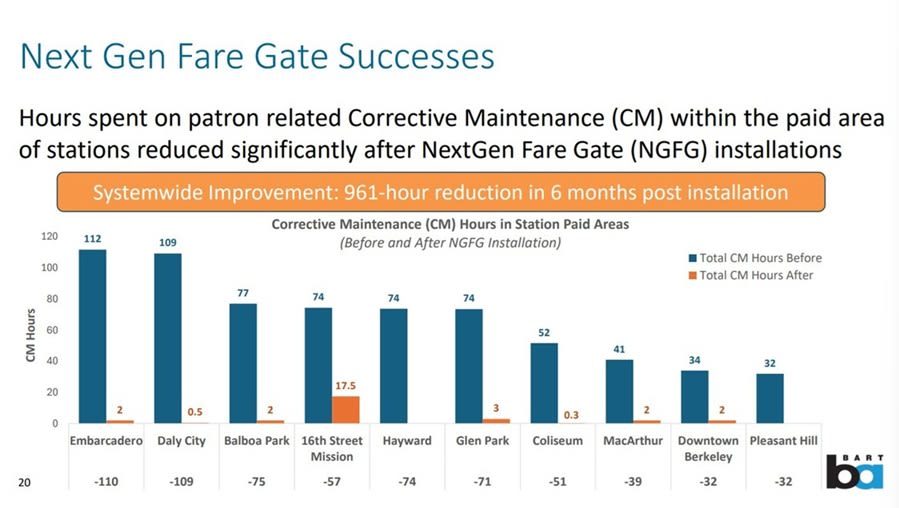

In fact, we have evidence that this fear is very rational. When BART installed ticket gates at their train stations that prevented people from riding for free — over the loud objections of progressives — crime on the train went down by 54%, and the amount of disorder and bad behavior on the train absolutely collapsed:

Fear of crime — often rational fear — also stops people from allowing train stations and bus stops in their neighborhood in the first place. There are a number of studies linking train stations and bus stops to increased crime, both in the immediate area and at areas linked to the same transit line. Criminals ride the bus and the train, so in a high-crime country like America, people don’t want trains and buses in their neighborhood. This is probably a big reason why almost no U.S. city has a good train system.

In other words, while car-centric suburbanization is partially about people wanting lots of cheap land and big houses and peace and quiet, part of it is a defense-in-depth against America’s persistently high crime rates.

As an American, when you go to a European city or an Asian city — or even to Mexico City — and you see pretty buildings and peaceful clean streets and there are nice trains and buses everywhere, what you are seeing is a lack of crime. The lack of crime is why people in those countries ride the train, and encourage train stations to be built in their neighborhoods instead of blocking them. The lack of crime is why people in those countries embrace dense living arrangements, which in turn enables the walkable mixed-use urbanism that you can enjoy only on vacation.

In other words, this tweet is right:

Of course, urbanism is not the only thing that benefits from low crime rates — health costs are lower, families are more stable, and of course fewer people die. But the big differences that Americans notice between the quality of life in their own cities and the seemingly better quality of life in other countries that are less rich on paper are primarily due to the fact that those other countries have gotten crime largely under control, while the U.S. has not.

As for the root causes of American crime, and what policies might bring it down to a more civilized level, that’s the subject for another post. The point of today’s post is simply to say that we can’t ignore our country’s sky-high crime rates just because we’ve lived with them our whole lives. Nor should we comfort ourselves with the fact that crime is down from the recent highs of 2021. We are still living in a country that has been devastated by violence and public disorder, and which has never really recovered from that. Someday soon we should think about getting around to fixing it.

Update: As if on cue, here’s a paper by Bencsik and Giles showing that electing a Republican prosecutor reduces crime and mortality rates:

This paper investigates the causal relationship between approaches taken by local criminal prosecutors—also called district attorneys—and community-level mortality rates. We leverage plausibly exogenous variation in prosecutorial approaches generated by closely contested partisan prosecutor elections, a context in which Republican prosecutorial candidates are commonly characterized as “tougher on crime.” Using data from hundreds of closely contested partisan elections from 2010 to 2019…we find that narrow election of a Republican prosecutor reduces all-cause mortality rates among young men ages 20 to 29 by 6.6%. This decline is driven predominantly by reductions in firearm-related deaths, including a large reduction in firearm homicide among Black men and a smaller reduction in firearm suicides and accidents primarily among White men. Mechanism analyses indicate that increased prison-based incapacitation explains about one third of the effect among Black men and none of the effect among White men. Instead, the primary channel appears to be substantial increases in criminal conviction rates across racial groups and crime types, which then reduce firearm access through legal restrictions on gun ownership for the convicted.

On one hand, progressives have to reckon with the fact that their prosecutors’ soft-on-crime approach is getting a bunch of Black men needlessly killed. On the other hand, conservatives need to reckon with the fact that the most important mechanism seems to be preventing people from owning guns. More about both of those things in the follow-up post.

The remaining difference is almost entirely due to traffic accidents, suicide, and violent crime.

I excluded a few small Caribbean nations like Trinidad and Tobago, Bahamas, and Guyana.

At this point, someone in the comments will ask me about Dobson (2002), who claimed that medical advances that prevent gunshot victims from dying have masked a big increase in attempted homicides. But we have tons of recent survey data on rates of violent crime victimization, and there was definitely a huge decline in assaults, gun violence, and so on in the 1990s. As for the difference between today and the 1930s, a more likely explanation is that many attempted murders went unreported or unprosecuted back then.

Note that progressives tend to staunchly oppose getting homeless people off the streets. When Zohran Mamdani reinstated homeless sweeps after realizing that pausing them would lead homeless people to die en masse from exposure to the elements, progressive activists were outraged.

2026-02-24 11:04:52

If you don’t like posts about AI, I have some bad news: For the next few years, there are probably going to be a lot of them. It’s not often one gets to live through an industrial revolution in real time, especially one that moves so quickly. There will be very few pieces of the economy — if any — that this revolution doesn’t touch, and it will have major implications for other things I write about (geopolitics, society, etc.). AI is not going to be a special, compartmentalized topic for a long time; it’s going to be central to a lot of what’s going on. If you find that boring, well, all I can say is, we don’t get to choose the times we live in.

Anyway, today’s post is about the macroeconomics of AI, so that’s fun. I started out writing about macro long ago, and I haven’t really kept up with it in recent years.

Every couple of weeks, someone comes out with a big post about how AI is changing everything, and the post goes viral and everyone talks about it for a few days. A couple of weeks ago it was Matt Shumer’s “Something Big is Happening”. This week it’s Citrini Research’s “THE 2028 GLOBAL INTELLIGENCE CRISIS” (yes, the title is in all caps):

The post paints a picture of a future in which AI disrupts lots of different kinds of white-collar work and service-industry business models in industries like software, finance, business services, and so on, and in which this disruption causes an economic crisis.

This is really two theses in one — a microeconomic thesis about which industries and jobs AI will disrupt, and a macroeconomic thesis about what this will do to the economy overall. People are debating both. For a counterargument to the idea that AI is about to take all the white-collar jobs, I recommend this post by John Loeber:

And I also recommend this post from January by Seb Krier, which of course doesn’t address the Citrini piece, but which does paint a vivid scenario for how humans might still have jobs in the age of AI.

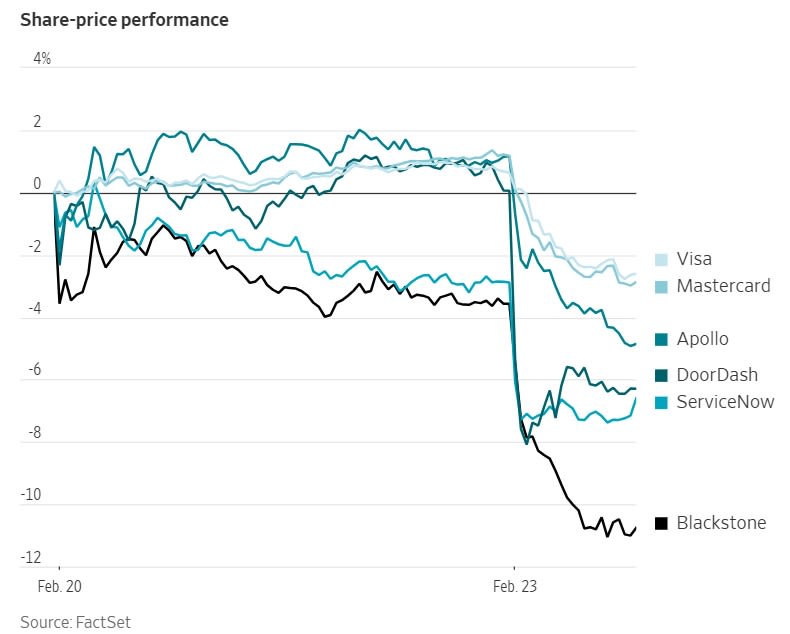

I don’t really have a dog in this microeconomic fight, because, frankly speaking, I don’t have an expert-level understanding of either the industries or the jobs in question. It has been interesting to see the market react to the Citrini post, though. A bunch of software and finance stocks fell, including many companies that Citrini mentioned by name:

This is pretty interesting, from a finance perspective. It’s pretty normal these days to see companies’ stocks falling based on news of AI’s disruptive potential — IBM just fell when Anthropic revealed that its AI models can handle COBOL,1 and a bunch of cybersecurity stocks fell a few days ago when Anthropic’s models found a bunch of security flaws.2 But those were real announcements of model capabilities; Citrini’s post was just a scenario for how some current business models could be disrupted.

Was that scenario really news? Did none of the analysts tasked with keeping tabs on Visa and Mastercard stock really think about the possibility of AI disruption until a blogger sketched out a sci-fi future mentioning those companies by name? I have my doubts. Instead, this smells more like a wave of sentiment — basically, a bunch of traders read the post, got spooked, and coordinated their panic-selling on the stocks that the post mentioned.

(The inclusion of DoorDash in the stocks that fell suggests this as well. DoorDash is no marvel of software engineering; it was always easily possible to clone the platform even before AI. Its profits are based on a first-mover advantage and network effect, which Claude Code can’t simply conjure up out of nothingness.)

But in any case, time will tell whether Citrini was right about those companies and those business models. I have a lot more to say about the macroeconomic thesis — the idea that the rapid destruction of a bunch of American companies will cause a financial crisis and a recession. Citrini posits an unemployment rate of over 10% — Great Recession levels — as well as a drop in consumption.

Citrini doesn’t use an explicit macroeconomic model, so we can’t really see what assumptions they’re making; it’s not clear how they think the economy works in the first place, so we don’t know exactly why they think the economy crashes. But we can make a couple of guesses. In fact, I see two vaguely plausible ways that an AI-driven service productivity boom could actually end up crashing the economy. Neither one is very likely, though.

2026-02-22 17:46:47

In case you haven’t heard, the Supreme Court just ruled many of Donald Trump’s tariffs illegal:

[T]he Supreme Court ruled that the unilaterally imposed [tariffs] were illegal…No longer does Trump have a tariff “on/off” switch…Future tariffs will need to be imposed by lengthy, more technical trade authorities — or through Congress…

In a 6-3 ruling, the Supreme Court said that affirming Trump's use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) would "represent a transformative expansion of the President's authority over tariff policy."…Chief Justice John Roberts said that IEEPA does not authorize the president to impose tariffs because the Constitution grants Congress — and only Congress — the power to levy taxes and duties.

This doesn’t mean that Trump’s tariffs are going to suddenly vanish. More are on the way. There are older laws passed by Congress in the 1960s and 1970s that authorize the President to raise tariffs under certain circumstances. Here’s a summary by the Yale Budget Lab:

[T]he president has other sources of legal authority to enact tariffs without further congressional action. These authorities generally fall into two groups: those that require investigations by federal agencies but have few if any restrictions on the eventual tariffs imposed (Sections 201, 232, and 301) and Section 122, which provides a temporary authority to impose tariffs without an investigation, but is limited to a 15 percent rate for only 150 days. There is another authority, under Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (otherwise known as Smoot-Hawley) that would allow the President to impose a 50 percent tariff with no investigation or time limitations, but no President has used this authority before, raising again concerns about future legal challenges.

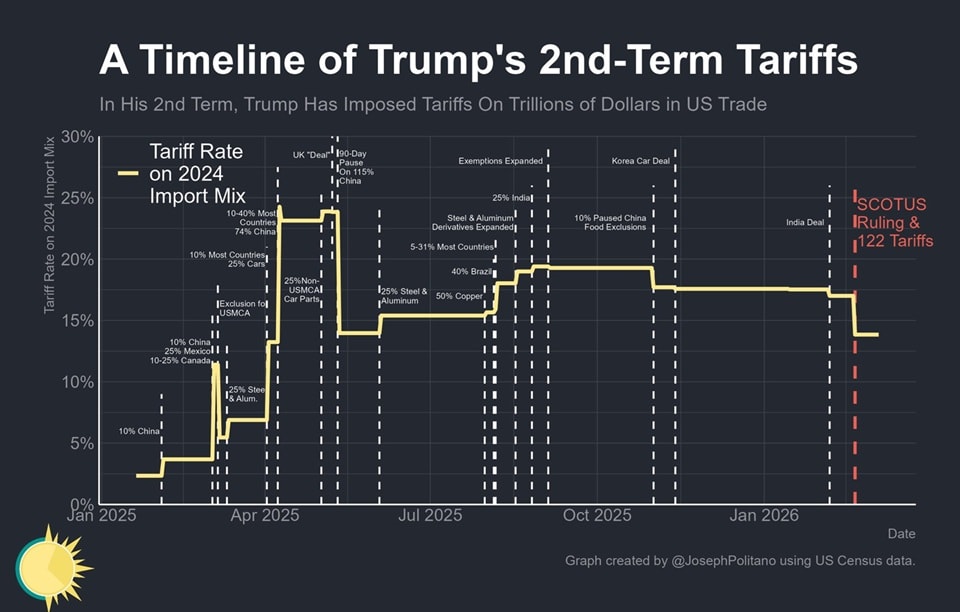

For now, all those other laws still stand, and Trump is going to use at least some of them. He immediately invoked one of the other laws, called Section 122, to put a 10% tariff on all imports from all countries, and then raised that to 15% a day later. This means the overall statutory tariff rate on U.S. imports (or at least, on the mix of imports from 2024), which would have fallen to around 9% after the SCOTUS ruling, will actually fall only a tiny bit:

But tariffs are very complex, and there are a ton of exemptions. Because these tariffs are more blanket than the ones SCOTUS just struck down, and because they interact with other tariffs that are still on the books, the new regime could raise effective tariff rates to even higher levels than before the SCOTUS decision.

That Section 122 tariff is supposed to be temporary — it only lasts 5 months — but Trump can presumably just renew it for another 5 months when it ends, until he gets sued again and it goes back to the Supreme Court. Then if that doesn’t work, he can use the various other laws, getting sued each time. In other words, Trump will be able to keep imposing large tariffs for the rest of his term in office.

So the fun continues. Whee!!

What was the point of these tariffs? It has never really been clear. Trump’s official justification was that they were about reducing America’s chronic trade deficit. In fact, the initial “Liberation Day” tariffs were set according to a formula based on America’s bilateral trade deficits with various countries.1 But trade deficits are not so easy to banish, and although America’s trade deficit bounced around a lot and shifted somewhat from China to other countries, it stayed more or less the same overall:

Economists don’t actually have a good handle on what causes trade deficits, but whatever it is, it’s clear that tariffs have a hard time getting rid of them without causing severe damage to the economy. Trump seemed to sense this when stock markets fell and money started fleeing America, which is why he backed off on much of his tariff agenda.

Trump also seemed to believe that tariffs would lead to a renaissance in American manufacturing. Economists did know something about that — namely, they recognized that tariffs are taxes on intermediate goods, and would therefore hurt American manufacturing more than they helped. The car industry and the construction industry and other industries all use steel, so if you put taxes on imported steel, you protect the domestic market for American steel manufacturers, but you hurt all those other industries by making their inputs more expensive.

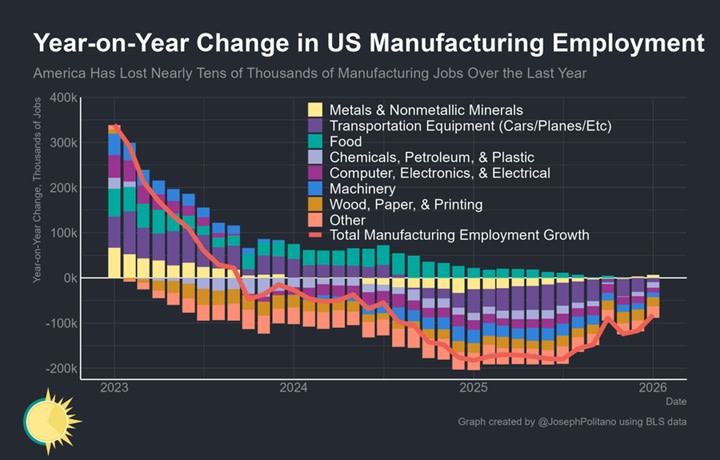

And guess what? The economists were right. Under Trump’s tariffs, the U.S. manufacturing sector has suffered. Here’s the WSJ:

The manufacturing boom President Trump promised would usher in a golden age for America is going in reverse…Manufacturers shed workers in each of the eight months after Trump unveiled “Liberation Day” tariffs, according to federal figures…An index of factory activity tracked by the Institute for Supply Management shrunk in 26 straight months through December…[M]anufacturing construction spending, which surged with Biden-era funding for chips and renewable energy, fell in each of Trump’s first nine months in office.

And here’s a handy chart, via Joey Politano:

Trump didn’t cause all of the slowdown — it began a few months before he took office — but manufacturers consistently report that tariffs are making things worse. Tariff cheerleaders like Oren Cass, who goes around shouting that economists don’t know anything and that economics isn’t a science, have gone strangely silent in the face of this clear victory for textbook economics.

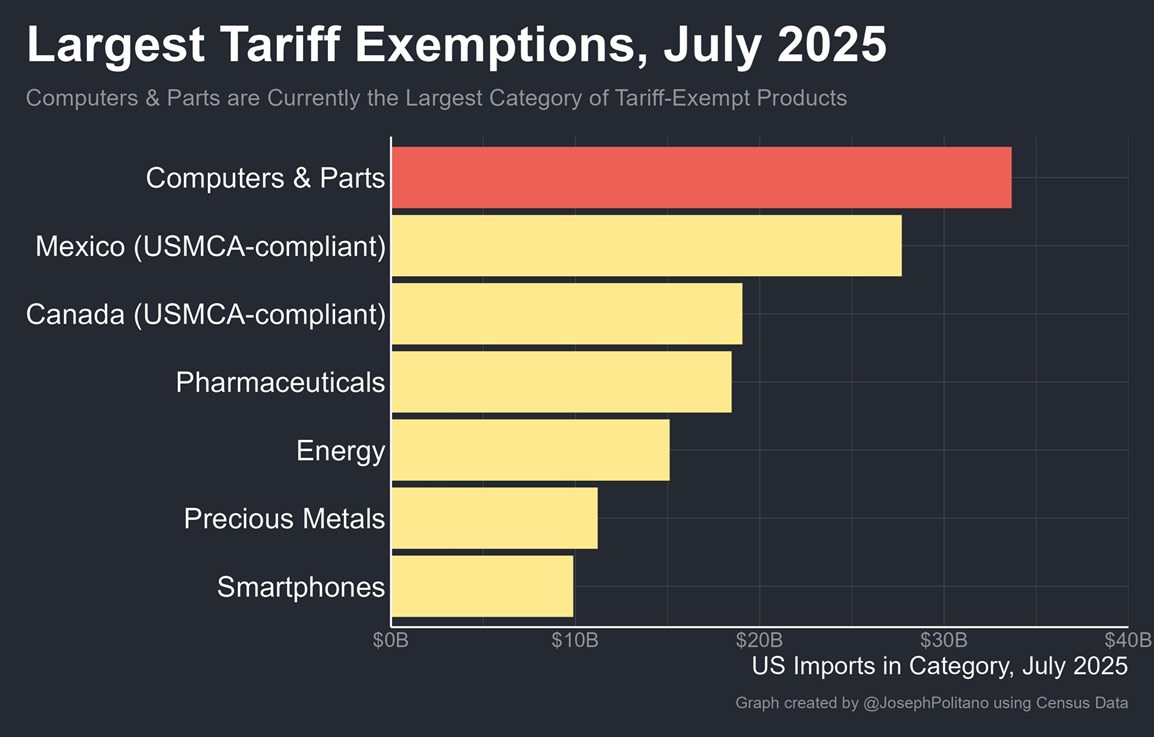

On some level, Trump — unlike pundits like Cass — seems to realize the basic economics of how tariffs hurt American industry. Recognizing the AI boom’s importance to the current economic expansion, he has granted huge exemptions for the computers that are being used to build AI data centers:

Macroeconomically, the tariffs haven’t been as big a deal as initially feared. Growth came in slightly weak in the final quarter of 2025, but that was mostly due to the government shutdown, and will rebound next quarter. Inflation keeps bumping along at a little bit above the official target, distressing the American consumer but failing to either explode or collapse. The President’s cronies have taken to holding up this lack of catastrophe as a great victory, but this sets the bar too low. If you back off of most of your tariffs and the economy fails to crash, you don’t get to celebrate — after all, the tariffs were ostensibly supposed to fix something in our economy, and they have fixed absolutely nothing.

Instead, the tariffs have mostly just caused inconvenience for American consumers, who have been cut off from being able to buy many imported goods. The Kiel Institute studied what happened to traded products after Trump put tariffs on their country of origin, and found out that they mostly just stopped coming:

The 2025 US tariffs are an own goal: American importers and consumers bear nearly the entire cost. Foreign exporters absorb only about 4% of the tariff burden—the remaining 96% is passed through to US buyers…Using shipment-level data covering over 25 million transactions…we find near-complete pass-through of tariffs to US import prices……Event studies around discrete tariff shocks on Brazil (50%) and India (25–50%) confirm: export prices did not decline. Trade volumes collapsed instead…Indian export customs data validates our findings: when facing US tariffs, Indian exporters maintained their prices and reduced shipments. They did not “eat” the tariff. [emphasis mine]

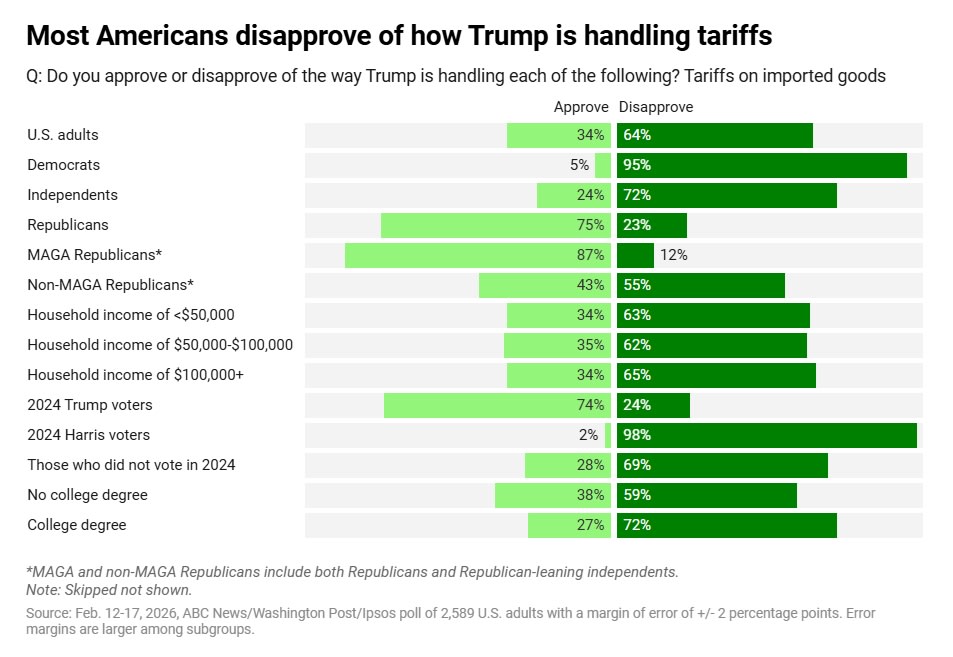

So it’s no surprise that the most recent polls show that Americans despise the tariffs:

A Fox News poll found the same, and Trump’s approval rating on both trade and the economy is underwater by over 16 points despite a solid labor market. Consumer sentiment, meanwhile, has crashed:

Trump has belatedly begun to realize the hardship he’s inflicting on voters. But instead of simply abandoning the tariff strategy, he’s issuing yet more exemptions and carve-outs in an attempt to placate consumers:

Donald Trump is planning to scale back some tariffs on steel and aluminium goods as he battles an affordability crisis that has sapped his approval ratings…The US president hit steel and aluminium imports with tariffs of up to 50 per cent last summer, and has expanded the taxes to a range of goods made from those metals including washing machines and ovens…But his administration is now reviewing the list of products affected by the levies and plans to exempt some items, halt the expansion of the lists and instead launch more targeted national security probes into specific goods, according to three people familiar with the matter.

Tariffs — or at least, broad, blanket tariffs on many products from many different countries — are simply a bad policy that accomplishes nothing while causing varying degrees of economic harm. But despite all his chicken-outs and walk-backs and exemptions, Trump is still deeply wedded to the idea. When news of the Supreme Court ruling reached him, he flew into a rage and accused the Justices of serving foreign interests:

He called the liberals a “disgrace to our nation.” But he heaped particular vitriol on the three conservatives [who ruled against him]. They “think they’re being ‘politically correct,’ which has happened before, far too often, with certain members of this Court,” Mr. Trump said. “When, in fact, they’re just being fools and lapdogs for the RINOs and the radical left Democrats—and . . . they’re very unpatriotic and disloyal to our Constitution. It’s my opinion that the Court has been swayed by foreign interests.”

JD Vance, rather ridiculously, called the decision “lawless”:

Why are the President and his loyalists so incensed over the SCOTUS decision? The tariffs are a millstone weighing down Trump’s presidency, and his various walk-backs confirm that he realizes this. It would have been smarter, from a purely political standpoint, to just let SCOTUS do the administration a favor and cancel the tariffs. Instead, Trump is going to the mat for the policy. Why?

One possibility is simply that Trump hates having his authority challenged by anyone. Tariffs were his signature economic policy — something he probably decided on after hearing people like Lou Dobbs complain about trade deficits back in the 1990s. To give up and admit that tariffs aren’t a good solution to trade imbalances would mean a huge loss of face for Trump.

Another possibility is that Trump ideologically hates the idea of trade with other nations, viewing it as an unacceptable form of dependency on foreigners. Perhaps by using ever-shifting uncertainty about who would be hit by tariffs next, he hoped to prod other countries into simply giving up and not selling much to the United States.

A third possibility is that tariffs offer Trump a golden opportunity for corruption and personal enrichment. Trump issues blanket tariffs, and then offers carve-outs and exemptions to various companies and/or their products. This means companies line up to curry favor with Trump and his family, in the hopes that Trump will grant them a reprieve.

But the explanation I find most convincing is power. If all Trump wanted was to kick out against global trade, the Section 122 tariffs and all the other alternatives would surely suffice. Instead, he was very specifically attached to the IEEPA tariffs that SCOTUS struck down. Those tariffs allowed Trump to levy tariffs on specific countries, at rates of his own choosing, as well as to grant specific exemptions. That gave Trump an enormous amount of negotiating leverage with countries that value America’s big market.

This is the kind of personal power that no President had before Trump. It allowed him to conduct foreign policy entirely on his own. It allowed him to enrich himself and his family. It allowed him to gain influence domestically, by holding out the promise of tariff exemptions for businesses that toe his political line. And it allowed him to act as a sort of haphazard economic central planner, using tariffs like a scalpel to discourage the kinds of trade and production that he didn’t personally like.

In other words, I think that although the tariffs had their origin in 1990s-era worries about trade deficits, they ended up as a way to make the Presidency more like a dictatorship. That is almost certainly why the Supreme Court struck the IEEPA tariffs down, citing concerns over presidential overreach instead of more technical considerations.2

For much of the modern GOP, I think, autocracy has become its own justification. To many Republicans, tariffs were good because they made the President powerful, and SCOTUS’ ruling is anathema because it pushes back on the imperial Presidency.

In this case, America’s democratic institutions held the line. But there will be a next case.

The formula, which was probably AI-generated, involved lots of bad assumptions.

For example, SCOTUS could have ruled that IEEPA was fine in general, but that trade deficits don’t constitute the kind of “national emergency” that would justify IEEPA’s use.

2026-02-20 18:49:56

Let’s continue with the AI theme. We’ve done the dire warnings of doom, so now let’s be a little more pragmatic and optimistic.

A friend called me up the other day and asked me what I thought Democrats could offer Americans in terms of economic policy in this day and age. We discussed the limitations of the progressive economic program that coalesced in the late 2010s and was implemented during the Biden years. We then talked about possibilities for how AI might affect the economy, and what Democrats could offer in various scenarios. I promised my friend I would write a post outlining my thoughts, so here you go.

My basic argument is that the next Democratic policy offering should be robust to uncertainty. AI technology is changing very fast, and it will probably end up changing other technologies very quickly as well — robotics, energy, software, and so on. That rapid technological progress creates great uncertainty. Looking even just 10 years into the future, we basically don’t know:

What kind of jobs humans will be doing (and which will pay well)

What the macroeconomy — inflation, growth, and employment — is going to look like

How the distributions of income and wealth will change

Those are essentially all of the biggest questions in economics, and we don’t really know any of them. So what do you do when you can’t predict the future? You come up with ideas that will be likely to work no matter what the future ends up looking like. In other words, you try to be robust. AI is like a storm that’s buffeting the whole economy; Democrats need to be the rock in that storm.

In fact, I have several ideas for how Democrats can create a robust economic offering even in the face of radical uncertainty. My three basic principles are:

Abundance

Government taking an ownership stake in the corporate system

Policies to promote human work

Before I talk about those, however, I want to briefly go over what the 2010s progressive program looked like, and why Democrats can’t just keep pushing that.

The progressive economic ideas of the 2010s were, in large part, a reaction to the Great Recession and to the rise of inequality since the 1970s. But they also had their roots in political considerations — progressive activism, and the need to manage the emerging Democratic political coalition.

In a nutshell, the progressive program was:

Have the government spend money to sustain full employment

Spend money on subsidizing health care, education, and child care

Spend money on cash benefits for people with children

Spend money on mitigating climate change

Fund this spending by taxing billionaires

Attack corporate power in order to reduce political opposition to the progressive agenda

This was a pretty cohesive program — there was at least a bit of real research to back up most of these ideas,1 and these proposals seemed like they would both satisfy the core Democratic interest groups while also potentially having broad appeal.

But it turned out there were lots of problems with this approach. The first, as I wrote back in 2024, was that it basically assumed we were still in the macroeconomic environment of 2009 or 2016:

In 2009 or maybe even 2016, the economy still had a shortage of aggregate demand — spending more money had the potential to create jobs while also bringing inflation back to target. In fact, a high-pressure economy, along with higher local minimum wage laws, did raise low-end wages disproportionately in the 2010s.

But by the time progressives actually got into power in 2021, progressives’ diagnosis was no longer correct. In the years after the pandemic, America’s main macroeconomic problem was no longer underemployment — it was inflation. And by pushing aggregate demand even higher with massive deficit spending, the Biden administration probably exacerbated that inflation.

The warnings were there in advance. In 2021, the macroeconomist Olivier Blanchard used a standard, simple Keynesian economic analysis — the same kind of back-of-the-envelope exercise that would have been screaming “spend more money!” back in 2009 — to predict that Biden’s American Rescue Plan would raise inflation. Progressives ignored these warnings and charged ahead anyway. The result — exacerbated inflation — probably contributed marginally to Kamala Harris’ election loss in 2024.

The second problem was the natural tension between providing jobs in care industries and actually providing care services cheaply to the American populace. If you subsidize health care, education, and child care, the prices of these things will go up. This is exactly what happened with artificially cheap student loans, which drove up the cost of college. I pointed this out in 2021:

The progressive retort was that it doesn’t matter if the price that care providers charge goes up, as long as the price consumers pay goes down. The subsidy makes up the difference — it makes care services feel cheaper to the public, but also creates jobs in those industries. This is expensive, of course, but progressives planned to square the circle by taxing billionaires.

The problem was that the billionaire taxes never happened. Biden and Harris and progressives in Congress made a lot of noise about taxing the super-duper-rich, but it turns out that it’s very hard to get super-duper-rich people’s money. It’s a lot easier to get money from millionaires instead of billionaires, but millionaires had become the Democrats’ base, so they were reluctant to do this. And so instead, subsidies for care industries became giant deficit-funded make-work programs.2

Meanwhile, core parts of the progressive agenda turned out not to be as popular as their creators had hoped. Cash benefits failed to garner broad support, and Americans ended up not caring that much about climate change.

This is not to say that the progressive economic program failed completely, either in an economic or in a political sense. A high-pressure economy really did lift wages at the bottom and reduce wage inequality. Biden’s cash benefits and climate subsidies did some good for a while. And the program probably did help Biden get elected in 2020.

Overall, though, the progressive program was pretty underwhelming. And more importantly, the economic situation has changed so much that the program is no longer relevant. Democrats can’t just cruise on autopilot on the promise of more health care subsidies, more child tax credits, more green jobs, and more promises of billionaire taxes. In the late 2020s and early 2030s, this will be neither a winning program nor an effective one.

Which brings me to my own ideas about what the Democrats should do next.

Abundance is one of the big ideas on the American left at the moment, and deservedly so. Instead of ideology about how to run an economy — big government, small government, etc. — it focuses on what Americans will get. It promises cheap housing, cheap energy, cheap food, cheap health care, etc.

This prioritization of goals over methods comes from the YIMBY movement. YIMBYism is being embraced by Democrats across the spectrum, from J.B. Pritzker to Zohran Mamdani:

Abundance is basically YIMBYism for everything.

Abundance is the right move for the Democrats because it deals with the cost of living, which is Americans’ most pressing concern right now. But it also provides a very smart and robust way of dealing with the disruptions from the rise of AI.

AI will disrupt patterns of specialization and comparative advantage across the economy. In simple terms, this means that a lot of people don’t know what kind of work they’ll be doing in ten years.

The traditional progressive approach to this uncertainty is to promise people jobs in certain industries — health care, education, etc. — that seem like they might be more resistant to AI. But while it’s true that those industries have provided a lot of jobs in recent years, that doesn’t mean they should function as a giant make-work program for people displaced by AI. That’s expensive and economically inefficient, and it very obviously raises questions about whether the people doing care jobs are really just on welfare.3

A second approach is to hand people cash. This is Andrew Yang’s preferred solution. But as we saw with Biden’s expanded Child Tax Credit, it can be hard to build political support for even a modest version of this sort of welfare program. A workable Universal Basic Income would cost far more than what Biden tried.

But abundance creates a third option here. If people know that they’ll have enough housing, food, energy, and the other basics of life, the threat of losing their jobs will be far less dire. And the cheaper the basics become, the more modest of a welfare check will be needed in order to sustain a minimum quality of life.

Democrats should therefore make it a priority to build more housing, build more energy, and provide more food and health care. This can mean cutting regulation, or it can also mean direct government provision. In general, it will mean a mix of both.

But in the age of AI, abundance will require a third approach: reserving resources for human consumption.

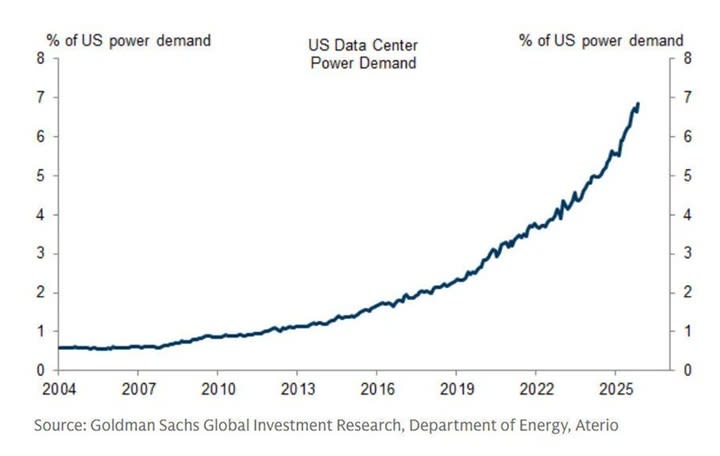

AI is incredibly hungry for computing power, and compute costs electricity. Data centers are consuming an exponentially rising fraction of America’s electric power production:

This means that AI and human consumers are going to increasingly be in direct competition for resources — electricity, land, and water. Right now it’s mostly electricity. But as AI continues to scale exponentially, hyperscalers will try to outbid farmers for land and convert their farms to data centers and power plants, driving up the cost of food. They will try to outbid residential real estate developers, making housing more expensive. In effect, AI will be muscling out the human race, without any army of robots involved.

And that’s a problem for Abundance Agenda 1.0. Abundance is about creating more supply, but if that supply just gets gobbled up by data centers, then abundance is failing.

The answer here is not to ban new data centers, as Bernie Sanders has called for. Instead, it’s to reserve some amount of land and other resources for human consumption — for food production, housing, and the production of electricity for households. This can be easily done with various zoning and land use policies. The implementation might be local and patchwork, but the message — “reserve resources for humanity” — is very simple.

This sort of “human reservation” policy fits very naturally into the overall abundance framework. It helps address both the cost-of-living problem and the fear of AI, and it’s complementary to efforts to produce more housing, energy, and so on.

One big worry with AI is that by substituting for human labor, it will decrease the fraction of the nation’s income that goes to human workers. It’s easy to imagine a dark future where the lucky people who own the robots get everything, while people who depend on their own effort and smarts to earn a living are forced to the margins of society.

In fact, labor’s share of national income has already been going down, since the turn of the century:

Worryingly, it took another sharp dive just in the third quarter of 2025. That probably isn’t AI — it’s too soon and too sudden — but a lot of people are going to be worried. And the longer trend is already disturbing.

The obvious solution here is redistribution. Contrary to what some progressives will tell you, the U.S. actually does a good job redistributing from the rich to the poor, and has been doing more and more of this over time:

The question is how to do it. These days, we mostly take from the rich using personal income taxes, and we give to the poor via government welfare and health care programs.

But if capital keeps eating the world, will we be able to do more of this? And will this satisfy the populace? I have my doubts. First of all, it turns out that it’s both politically and logistically difficult to raise taxes by a meaningful amount of GDP:

This is partly because rich people are pretty good at tax avoidance, and because Republicans periodically come into power and cut taxes.

There is another way. The government could use its tax revenue to acquire shares in companies. Then it would have a claim on those companies’ future profits in perpetuity. If Nvidia and OpenAI and Google end up eating more and more of the economy, and the government owns part of those companies, then the government can just redistribute part of those companies’ profit to the American people — either via welfare programs, or just by mailing everyone a dividend check.

This latter approach is what the Alaska Permanent Fund does. A U.S. sovereign wealth fund would do the same thing, except instead of getting its money from resource revenues, it would get its money from corporate dividends and share buybacks. Essentially, if AI is the new oil — a source of boundless wealth that needs very few human beings to produce — then a U.S. sovereign wealth fund should have a claim on that revenue stream.

Donald Trump has proposed creating a sovereign wealth fund, and has already started having the U.S. government take equity stakes in various companies. But this is a haphazard approach — it means the government owns part of some companies and not others, which can limit competition, distort the markets, and open up avenues for corruption.

The Democrats should simply systematize the process — have the U.S. sovereign wealth fund automatically buy a stake in the entire stock market, as well as large, established closely held companies like OpenAI. That way, no matter which companies succeed, the government will own a piece of that success. If capital’s share of income increases, the government can redistribute it, supplementing dwindling labor income.

There is a big question of how the fund would be funded. It could be funded by deficit spending, or it could be funded by increased taxes. One possible solution would be a temporary increase in the corporate tax, with the proceeds earmarked for the sovereign wealth fund. Companies would basically be handing money over to the government via corporate tax payments, only to see that money come right back to them as share purchases.

At this point, someone will probably point out that corporate taxes themselves work like government stock ownership — if you take 20% of a company’s profits every year, that’s not too different from owning 20% of it. But in fact, the sovereign wealth fund approach has several advantages.

First of all, like every other type of tax, corporate tax rates can be lowered as soon as a Republican gets into office — in fact, Trump did this in 2017. But Republicans are unlikely to have the government dump corporate shares, as this would cause the stock market to tank. Sovereign wealth funds are thus probably a lot more robust to the changing winds of political fortune.

It’s also possible to fund a sovereign wealth fund using taxes that are less distortionary than corporate tax. That would allow companies to reinvest more of their earnings, so that the payouts would be greater down the line.

Finally, a sovereign wealth fund probably conveys some intangible political advantages. Taxes naturally seem adversarial — a government taking money from its own citizens. Government ownership stakes, on the other hand, seem like an alignment of interests — the people of the nation having a direct stake in the success of their country’s businesses. Although the math isn’t much different, the optics could convey more of a message of “We’re all in this together” — a very Rooseveltian idea. And although the idea of a sovereign wealth fund might seem wonkish and cerebral, the slogan that everyone in America deserves a stake in the AI that their nation created could have some real populist appeal.

In fact, a few people on the left and in the center have been proposing this idea for a while. Democrats should do it.

Finally, the rise of AI gives our leaders a chance to do something they ought to have done long ago — give American companies an incentive to invest more in their human workers.

Companies don’t train their employees nearly as much as they ought to. The reason is well-known — if you spend a bunch of money and time training an employee, and then they leave, you’ve paid to train someone else’s worker. This is why U.S. corporate training is so paltry and halfhearted — our workers are highly mobile.

In the age of AI, this problem will be even worse. Old types of work are becoming obsolete every day. In order to properly value their human workers, companies essentially need to engage in continuous research, experimenting with new types of workflow and complementarity. But if a company spends time and money figuring out new ways for humans to work with AI, those new insights will quickly spread to other companies, including their competitors. So instead, companies have a perverse incentive to simply try to replace human workers with AI, even if using both together would actually be more productive!4

In other words, on-the-job training is now a public good. And public goods need to be subsidized by the government.

The easiest way to do this is to have governments subsidize hiring. By some accounts, hiring of new graduates at big tech companies has almost completely collapsed:

The government can put its thumb on the scale for the humans here. It can pay companies to hire employees for at least two years. This will give companies an incentive to have more humans around. And while a company has some humans around, it might as well try to figure out how to get valuable work out of them, by having them try using AI in various ways.

Essentially, the government will be subsidizing private-sector research in the field of human-computer interaction.

If AI starts causing massive layoffs in white-collar industries, instead of just slowdowns in hiring, the government can also give temporary retention incentives. If keeping humans around for a while becomes cheap, companies will go back to hoarding labor like they did before the 1980s. And while those workers stick around, companies will have an incentive to find new types of jobs for them to do.

Hiring incentives and temporary retention incentives are not the same thing as paying companies to employ more humans over the long run. I am not calling for the government to put its thumb on the scale for humans over AIs. Economically speaking, my idea is really just a research subsidy. But importantly, the political optics of my idea might be just as good — in an age when everyone is scared of being replaced by machines, American workers will probably appreciate the government paying companies to hire humans.

All of these policies I’ve suggested are things that don’t really depend on how AI progresses over the next decade. They work just as well in a world of total human replacement as they do in a world where AI goes bust. These are rock-in-the-storm policies, meant to shield American workers from the winds of technological uncertainty and rapid change.