2026-03-14 02:29:13

1M context is now generally available for Opus 4.6 and Sonnet 4.6

Here's what surprised me:Standard pricing now applies across the full 1M window for both models, with no long-context premium.

OpenAI and Gemini both charge more for prompts where the token count goes above a certain point - 200,000 for Gemini 3.1 Pro and 272,000 for GPT-5.4.

Tags: ai, generative-ai, llms, anthropic, claude, llm-pricing, long-context

2026-03-14 01:14:29

Simply put: It’s a big mess, and no off-the-shelf accounting software does what I need. So after years of pain, I finally sat down last week and started to build my own. It took me about five days. I am now using the best piece of accounting software I’ve ever used. It’s blazing fast. Entirely local. Handles multiple currencies and pulls daily (historical) conversion rates. It’s able to ingest any CSV I throw at it and represent it in my dashboard as needed. It knows US and Japan tax requirements, and formats my expenses and medical bills appropriately for my accountants. I feed it past returns to learn from. I dump 1099s and K1s and PDFs from hospitals into it, and it categorizes and organizes and packages them all as needed. It reconciles international wire transfers, taking into account small variations in FX rates and time for the transfers to complete. It learns as I categorize expenses and categorizes automatically going forward. It’s easy to do spot checks on data. If I find an anomaly, I can talk directly to Claude and have us brainstorm a batched solution, often saving me from having to manually modify hundreds of entries. And often resulting in a new, small, feature tweak. The software feels organic and pliable in a form perfectly shaped to my hand, able to conform to any hunk of data I throw at it. It feels like bushwhacking with a lightsaber.

— Craig Mod, Software Bonkers

Tags: vibe-coding, ai-assisted-programming, generative-ai, ai, llms

2026-03-13 11:44:34

Shopify/liquid: Performance: 53% faster parse+render, 61% fewer allocations

PR from Shopify CEO Tobias Lütke against Liquid, Shopify's open source Ruby template engine that was somewhat inspired by Django when Tobi first created it back in 2005.Tobi found dozens of new performance micro-optimizations using a variant of autoresearch, Andrej Karpathy's new system for having a coding agent run hundreds of semi-autonomous experiments to find new effective techniques for training nanochat.

Tobi's implementation started two days ago with this autoresearch.md prompt file and an autoresearch.sh script for the agent to run to execute the test suite and report on benchmark scores.

The PR now lists 93 commits from around 120 automated experiments. The PR description lists what worked in detail - some examples:

- Replaced StringScanner tokenizer with

String#byteindex. Single-bytebyteindexsearching is ~40% faster than regex-basedskip_until. This alone reduced parse time by ~12%.- Pure-byte

parse_tag_token. Eliminated the costlyStringScanner#string=reset that was called for every{% %}token (878 times). Manual byte scanning for tag name + markup extraction is faster than resetting and re-scanning via StringScanner. [...]- Cached small integer

to_s. Pre-computed frozen strings for 0-999 avoid 267Integer#to_sallocations per render.

This all added up to a 53% improvement on benchmarks - truly impressive for a codebase that's been tweaked by hundreds of contributors over 20 years.

I think this illustrates a number of interesting ideas:

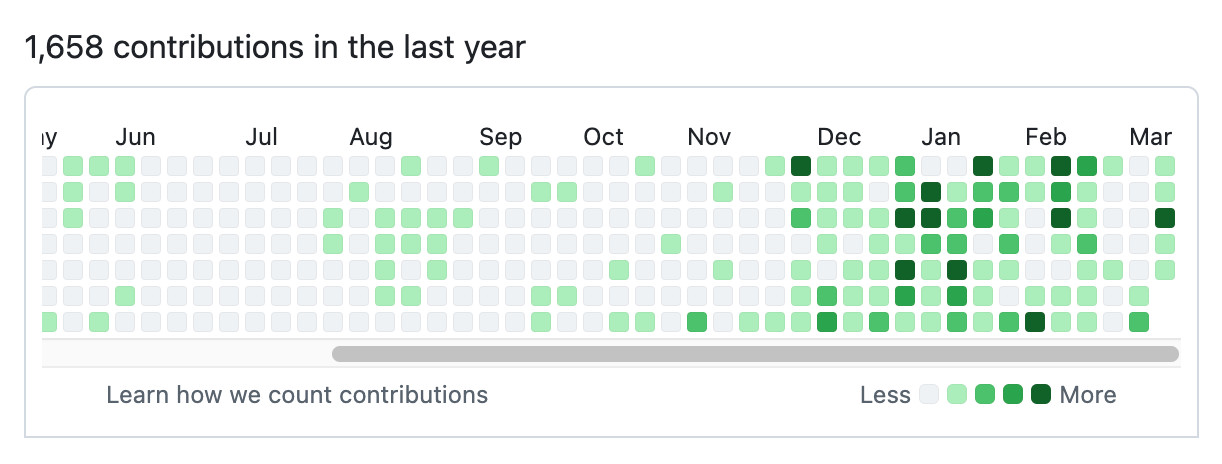

Here's Tobi's GitHub contribution graph for the past year, showing a significant uptick following that November 2025 inflection point when coding agents got really good.

He used Pi as the coding agent and released a new pi-autoresearch plugin in collaboration with David Cortés, which maintains state in an autoresearch.jsonl file like this one.

Via @tobi

Tags: django, performance, rails, ruby, ai, andrej-karpathy, generative-ai, llms, ai-assisted-programming, coding-agents, agentic-engineering, november-2025-inflection, tobias-lutke

2026-03-13 04:08:55

MALUS - Clean Room as a Service

Brutal satire on the whole vibe-porting license washing thing (previously):Finally, liberation from open source license obligations.

Our proprietary AI robots independently recreate any open source project from scratch. The result? Legally distinct code with corporate-friendly licensing. No attribution. No copyleft. No problems..

I admit it took me a moment to confirm that this was a joke. Just too on-the-nose.

Via Hacker News

Tags: open-source, ai, generative-ai, llms, ai-ethics

2026-03-13 03:23:44

Coding After Coders: The End of Computer Programming as We Know It

Epic piece on AI-assisted development by Clive Thompson for the New York Times Magazine, who spoke to more than 70 software developers from companies like Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, plus other individuals including Anil Dash, Thomas Ptacek, Steve Yegge, and myself.I think the piece accurately and clearly captures what's going on in our industry right now in terms appropriate for a wider audience.

I talked to Clive a few weeks ago. Here's the quote from me that made it into the piece.

Given A.I.’s penchant to hallucinate, it might seem reckless to let agents push code out into the real world. But software developers point out that coding has a unique quality: They can tether their A.I.s to reality, because they can demand the agents test the code to see if it runs correctly. “I feel like programmers have it easy,” says Simon Willison, a tech entrepreneur and an influential blogger about how to code using A.I. “If you’re a lawyer, you’re screwed, right?” There’s no way to automatically check a legal brief written by A.I. for hallucinations — other than face total humiliation in court.

The piece does raise the question of what this means for the future of our chosen line of work, but the general attitude from the developers interviewed was optimistic - there's even a mention of the possibility that the Jevons paradox might increase demand overall.

One critical voice came from an Apple engineer:

A few programmers did say that they lamented the demise of hand-crafting their work. “I believe that it can be fun and fulfilling and engaging, and having the computer do it for you strips you of that,” one Apple engineer told me. (He asked to remain unnamed so he wouldn’t get in trouble for criticizing Apple’s embrace of A.I.)

That request to remain anonymous is a sharp reminder that corporate dynamics may be suppressing an unknown number of voices on this topic.

Tags: new-york-times, careers, ai, generative-ai, llms, ai-assisted-programming, press-quotes, deep-blue

2026-03-13 00:28:07

Here's what I think is happening: AI-assisted coding is exposing a divide among developers that was always there but maybe less visible.

Before AI, both camps were doing the same thing every day. Writing code by hand. Using the same editors, the same languages, the same pull request workflows. The craft-lovers and the make-it-go people sat next to each other, shipped the same products, looked indistinguishable. The motivation behind the work was invisible because the process was identical.

Now there's a fork in the road. You can let the machine write the code and focus on directing what gets built, or you can insist on hand-crafting it. And suddenly the reason you got into this in the first place becomes visible, because the two camps are making different choices at that fork.

— Les Orchard, Grief and the AI Split

Tags: les-orchard, ai-assisted-programming, generative-ai, ai, llms, careers, deep-blue