2026-02-13 02:00:44

Through no fault of Apple, Face ID is having a moment — and not in a good way.

Sure, the biometric security feature works as well as it ever does, using a face scan to unlock your iPhone, confirm mobile payments and generally an extra layer of protection between your digital data and the prying eyes of the outside world.

But we live in a time of increasing unrest, and with it comes a concern about biometric security features in general. Run afoul of what purports to be law-and-order these days, and your own face can be used against you by police who can compel you to use Face ID unlocking against your will. A security writer at PC Mag goes so far as to suggest you should stop using Face ID entirely.

I’m not sure I want to take that drastic a step with my own iPhone. While concerns about biometric locks are certainly valid, I find Face ID pretty convenient to use when I’m out and about and my phone remains firmly in my possession. Glancing at my iPhone to unlock is certainly quicker than tapping out a passcode every time, and I like using Face ID to lock down everything from health data in my health care provider’s app to images I’ve got stashed in separate Photos folders.

That said, when I attend a protest (and it seems like I’m showing up at a lot of those lately), I do disable Face ID before heading out. The protests I’m attending haven’t ever gotten out of hand, but better safe than sorry, I reckon. While there’s not much stopping law enforcement from making you use your face or thumbprint to unlock a device, you aren’t compelled to share your passcode if you’re detained.

Turning off Face ID requires you to dive into the Settings app, tapping the Face ID & Passcode menu and then entering in that passcode when prompted. Only then can you toggle off the feature. And while that’s simple enough to do, it’s not a feature you can turn off discretely or quickly should you remember that Face ID is enabled as someone’s approaching you with ill intent.

There’s a shortcut of sorts: Just press and hold the side button on the right side of your iPhone at the same time you press and hold the volume-up button. iPhone veterans will recognize this as the button combo that brings up the Slide to Power Off command, which is exactly what will happen. As a neat bonus feature, you’ll even get some haptic feedback to let you know that the Slide to Power Off screen has appeared, allowing you to discretely pull of this manuever without even looking at your phone.

“But I just want to shut down Face ID, not power off my iPhone,” you may be saying. And my friend, shutting down Face ID is exactly what you’ve just done.

Tap the Cancel button on the Slide to Power Off Screen, and you’ll bring up your phone’s lock screen. Only now, the only way to unlock your iPhone is to enter a passcode. Face ID remains disabled until the next time you unlock your phone, giving you some measure of protection from having the Face ID feature used against you.

As a workaround, the Slide to Power Off move will do in a pinch. But I’d like there to be an even easier way to turn off Face ID, whether that’s through a Shortcut or with the help of Siri.

Poking around the built-in Shortcuts app on the iPhone, you can find pre-populated controls for silencing your phone, adjusting connectivity or the iPhone’s display, and more. But if there’s a way to quickly access the Face ID & Passcode menu in the Settings app, I couldn’t find it. (You can use Shortcuts’s Open URL action and the URL pattern prefs:root=PASSCODE to create an action that opens it, but you’ll still need to enter your password and flip the switch manually.) Likewise, there’s no tappable shortcut in the Control Center, which would seem like a natural place for a quick on-screen way to turn off Face ID. (You could even put the shortcut right there on the lock screen now that we’re firmly living in the brave new world of iOS customization.)

Likewise, Siri is no help when it comes to handling Face ID management. In the current version of iOS 26, a simple “Turn off Face ID command” will have Siri apologetically telling you that it doesn’t understand what you’re talking about. Perhaps that could be some of the smarts Siri is supposed to pick up in a coming update to iOS 26.

And really, this is the sort of thing Apple should add. The company makes the privacy features of its products a central part of the case for why you should buy Apple, with most of the recent TV spots focusing on keeping your browsing data private. But I would contend an even bigger privacy concern would be having everything that’s stored on your iPhone—text messages, emails, photos—made available on command to a some mask-wearing federal agent just because you’re using a biometric feature as intended.

The central role that phones play in our lives coupled with uncertain times at home and abroad have people rethinking how they should approach Face ID. Apple needs to be doing the same.

2026-02-12 05:07:56

Our best automations on macOS or iOS, our expense tracking tools, online age verification, and the fitness devices we’ve used recently.

2026-02-12 01:00:29

Sometimes I can’t help myself.

The other day, while watching an episode of “Animal Control”1, I realized that I have been writing about technology so long that I can’t even turn off my brain to stop from shouting troubleshooting advice at the made-up people on my TV during a half-hour of light comedy.

Here’s the scenario: Our hero, Seattle Animal Control Office Frank Shaw (expertly played by Joel McHale), has been roped into ferrying around his arch-nemesis, a Cesar Millan-esque dog whisperer played by guest star Ken Jeong. (Kudos to you if you immediately picked up on this mini-“Community” reunion.) Joel McHale’s character has recorded a video on his phone of Ken Jeong having an encounter with an aggressive dog that will cause the latter no small amount of professional and personal embarrassment.

Ken Jeong manages to guilt Joel McHale into deleting the video from his phone by spinning a sob story that (if you know the kinds of characters Ken Jeong plays) is completely made up. But Joel McHale falls for it and deletes the video, only to have Ken Jeong turn the tables and cause McHale no small amount of professional and personal embarrassment. Joel McHale is left to fume about his missed opportunity.

“There’s gotta be a way to recover lost footage,” he says, while impotently turning his phone’s flashlight on.

And where other people might chuckle at this little interlude, a person in my position finds himself shouting at the screen, “There is! There is, you big galoot!” as if Joel McHale is going to answer back.

We do not have to guess as to what phone Joel McHale’s character is using — it is very clearly an iPhone. Given the camera array that I spotted when reviewing the footage with the same frame-by-frame intensity that JFK conspiracy theorists study the Zapruder film, I’d suggest that it’s an iPhone 16 Pro, but that’s neither here nor there. The point is, Frank is using a recent iPhone, so we’ll assume the on-board software is relatively up-to-date.

Everybody who’s used any piece of tech for any length of time knows that nothing’s truly deleted — at least not right away. In the case of photos and videos that you remove from your iPhone, by default they sit in a folder for 30 days before they disappear completely.

In the case of this particular “Animal Control” episode, all Frank would have to do to get that damning video back would be to fire up the Photos app on his iPhone, tap on the Collections tab and find the Recently Deleted folder tucked away in the Utilities section. Frank would tap on the deleted video, select Recover, and sit back and smile while that nasty Ken Jeong finally gets what’s coming to him.

Near as I can tell, there’s no way to disable the Recently Deleted folder feature so that deleted photos and videos go directly to that big trash can in the sky, nor is there a way to extend the stay of execution beyond those 30 days.

Frank could also avoid these kind of situations altogether by backing up his photos and videos to a third-party cloud service. (iCloud wouldn’t work in this case, as deleting things off your phone removes them from Apple’s syncing service.) But considering his tendency to repeatedly turn on his iPhone’s flashlight, that might be a backup best practice beyond his skill set.

2026-02-12 00:00:00

Lex does the robot, Dan is popular online and Moltz enjoyed the fireworks.

2026-02-10 22:39:22

The other day a Slack pal wondered aloud if there was a way to remove a previous recipient from a family member’s iPhone. The address wasn’t in their contacts, but it kept showing up in the autocomplete for the recipient line.

This tickled something in my brain and sure enough, I wrote about this very topic more than a decade ago—but I only covered how to do it on the Mac. Which got me wondering if it was possible to do on iOS.

Sure enough, it is, but you’d be excused for not finding it, since it’s a bit buried.

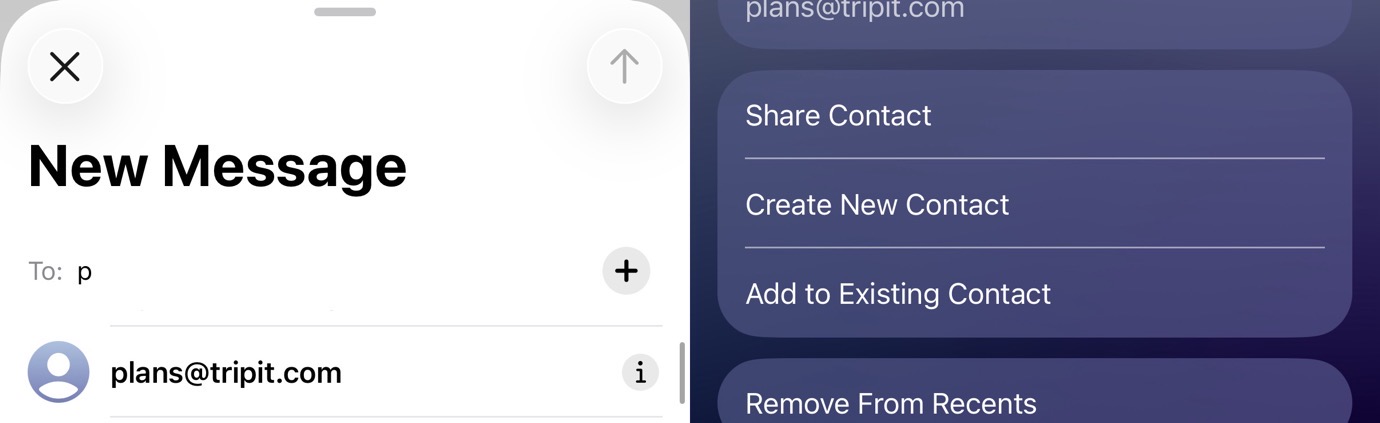

First, start typing the address in Mail’s To field until you see it show up in the dropdown menu. If it’s not in your contacts1 you’ll see it has a little “i” icon next to it. Tap that to bring up a screen where you can add it to your contacts or, more relevantly, scroll to the bottom and you’ll find “Remove From Recents.” Tap that and it should banish it…well, at least until you send them another email.

So there we are, only eleven years later. And, if you’re wondering, the macOS instructions above still work, even if the UI looks a little different these days.

2026-02-10 06:44:41

Eddy Cue comes down hard on a would-be Apple service; we try to figure out what the new low-end Mac laptop might be, Tim Cook calls an important meeting to say a lot of words, and we tackle all aspects of the Super Bowl plus some curling!