2026-02-06 00:24:16

My New Org to Solve Consciousness (or Die Trying)

A Rogue AI Community That Wasn’t

David Foster Wallace Is Still Right 30 Years Later

The Cost of AI Agents is Exploding

The Diary of a 100-Year-Old

AI Solving Erdős Problems is (So Far) Mostly Hype

Cow Tools Are Real

From the Archives

Comment, Share Anything, Ask Anything

As is obvious from the state of confusion around AI, technology has outstripped consciousness science, leading to a cultural and scientific asymmetry. This asymmetry needs to be solved ASAP.

I think I’ve identified a way. I’ve just released more public details of Bicameral, a new nonprofit research institute devoted to solving consciousness via a unique method. You can read about it at our website: bicamerallabs.org.

Rather than chasing some preconceived notion of consciousness, we’re making the bounds for falsifiable scientific theories of consciousness as narrow as possible.

Why do this as a nonprofit research institute? I’ve worked in academia (on and off) for a long time now. It’s not that funding for such ideas is completely impossible—my previous research projects have been funded by sources like DARPA, the Templeton Foundation, and the Army Research Office. But for this, academia is mismatched. It’s built around one-off papers, citation metrics, small-scale experiments run in a single lab, and looking to the next grant. To solve consciousness, we need a straight shot all the way through to the end.

If you want to help this effort out, the best thing you can do is connect people by sharing the website. If you know anyone who should be involved with this, point them my way, or to the website. Alternatively, if you know of any potential funders that might want to help us crack consciousness, please share the website with them, or connect us directly at: [email protected].

We are now several years into the AI revolution and the fog of war around the technology has lifted. It’s not 2023 anymore. We should be striving to not run around like chickens with our heads cut off and seek clearer answers. Consider the drama around the AI social media platform “Moltbook.”

A better description is that an unknown number of AI agents posted a bunch of stories on a website. Many of the major screenshots were fake, as in, possibly prompted or created by humans (one screenshot with millions of views, for instance, was about AIs learning to secretly communicate… while the owner of that bot was a guy selling an AI-to-AI messaging app).

In fact, the entire website was vibe-coded and riddled with security errors, and the 17,000 human owners don’t match the supposed 1.5 million AI “users,” and people can’t even log in appropriately, and bots can post as other bots, and actually literally anyone can post anything—even humans—and now a lot of the posts have descended to crypto-spam. You can also just ask ChatGPT to simulate an “AI reddit” and get highly similar responses without anything actually happening, including stuff very close to the big viral “Wow look at Moltbook!” posts (remember, these models always grab the marshmallow, and without detailed prompting give results that are shallow and repetitive). Turns out, behind examples of “rogue AIs” there are often users with AI psychosis (or using them mostly for entertainment, or to scam, etc.).

Again, the fog of war is clearing. We actually know that modern AIs don’t really seem to develop evil hidden goals over time. They’re not “misaligned” in that classic sense. When things go badly, they mostly just… slop around. They slop to the left. They slop to the right. They slop all night.

A recent paper “The Hot Mess of AI” from Anthropic (and academic co-authors) has confirmed what anyone who is not still in 2023 and scared out of their minds about GPT-4’s release can see: Models fail not by developing mastermind evil plans to take over the world but by being hot messes.

Here’s the summary from the researchers:

So the fuss over the Reddit-style collaborative fiction, “Moltbook,” was indeed literally this meme, with the “monsters” played by hot messes of AIs.

There is no general law, or takeaway, to be derived from it. Despite many trying to make it so.

In comparison to Moltbook, the “AI village” has existed for almost a year now. And in the AI village, the exact same models calmly and cooperatively accomplish tasks (or fail at them). Right now they are happily plugging away at trying to break news before other outlets report it. Most have failed, but have given it their all.

What’s the difference between Moltbook and the AI village? You’re never gonna believe this. Yes, it’s the prompts! That is, even when operating “autonomously,” how the models behave depends on how they’re prompted. And that can be from a direct prompt, or indirectly via context, in the “interact with this” sort of way, which they are smart enough to take a hint about. They are always guessing at how to please their users, and if you point them to a schizo-forum with “Hey, post on this!” they will… schizo-post on the schizo-forum.

Infinite Jest turned 30 this month. And yes, I confess to being a “lit bro” who enjoys David Foster Wallace (I guess that’s the sole qualification for being a “lit bro” these days). Long ago, all of us stopped taking any DFW books out in public, due to the ever-present possibility that someone would write a Lit Hub essay about us. However, in secret rooms unlocked to a satisfying click by pulling a Pynchon novel out from our bookshelf, we still perform our ablutions and rituals.

But why? Why was DFW a great writer? Well, partly, he was great because his concerns—the rise of entertainment, the spiritual resistance of the march of technology and markets, the simple absurdity of the future—have become more pressing over time. It’s an odd prognosticating trick he’s pulled. And the other reason he was great is because that voice, that logorrheic stream of consciousness, a thing tight with its own momentum, is itself also the collective voice of contemporary blogging. Lessened a bit, yes, and not quite as arch, nor quite as good. But only because we’re less talented. Even if bloggers don’t know it, we’re all aping DFW.

Another thing that made him great was the context he existed in as a member of the “Le Conversazioni” group, which included Zadie Smith, Jonathan Franzen, and Jeffrey Eugenides (called so because they all attended the Le Conversazioni literary gathering together, leaving behind a charming collection of videos you can watch on YouTube).

It’s an apt name, because they were the last generation of writers who seemed, at least to me, so firmly in conversation together, and had grand public debates about the role of genre vs. literary fiction, or what the purpose of fiction itself was, and how much of the modern-day should be in novels and how much should be timeless aspects of human psychology, and so on. Questions I find, you know, actually interesting.

Compare that to the current day. Which still harbors, individually, some great writers! But together, in conversation? I just don’t find the questions that have surrounded fiction for the past fifteen years particularly interesting.

A wayward analogy might help here. Since it’s become one of my kids’ favorite movies, I’ve been watching a lot of Fantasia 2000, Disney’s follow-up to their own great (greatest?) classic, the inimitable 1940 Fantasia. In its half-century-distant sequel, Fantasia 2000, throwback celebrities from the 1990s introduce various musical pieces and the accompanying short illustrated films. James Earl Jones, in his beautiful sonorous bass, first reads from his introduction that the upcoming short film “Finally answers that age-old question: What is man’s relationship to Nature?”

But then Jones is handed a new slip containing a different description and says “Oh, sorry. That age-old question: What would happen if you gave a yo-yo to a flock of flamingos? … Who wrote this?!”

And that’s what a lot of the crop of famous millennial writers after the Le Conversazioni group seem to me: like flamingos with yo-yos.

2026-01-26 23:18:23

The first short story I ever wrote was about a teenager who goes to shovel his grandmother’s driveway during a record snowstorm. Before leaving, he does some chores in his family’s barn, bringing along his old beloved dog. But he forgets to put the dog back in—forgets about her entirely, in fact—and so walks by himself down the road to his grandmother’s house. Enchanted by the snow, he has many daydreams, fantasizing about what his future life will hold. After the arduous shoveling, he has an awkward interaction with his grandmother. Finally, hours later, he returns home. There, he finds his old beloved dog, curled up in a small black circle by the door amid the white drifts, dead.

I don’t know why I wrote that story. Or maybe I do—I, a teenager just like my main character (including the family barn and the grandmother’s house down the road), had just read James Joyce for the first time. And Joyce’s most famous story from his collection Dubliners, “The Dead,” ends with this:

Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Snow is the dreamworld, and so snow is death too. It’s both. The veil between worlds is thin after a snow. One of our favorite family movies is the utterly gorgeous 1982 animation and adaptation of The Snowman. Like the book, it is wordless, except the movie begins with a recollection:

I remember that winter because it brought the heaviest snow that I had ever seen. Snow had fallen steadily all night long, and in the morning I woke in a room filled with light and silence. The whole world seemed to be held in a dream-like stillness. It was a magical day. And it was on that day I made the snowman.

The Snowman comes alive as a friendly golem and explores the house with the boy who built him, learning about light switches and playing dress up, before revealing that he can fly and whisking the child away to soar about the blanketed land.

So too do we own a 1988 edition of The Nutcracker that has become a favorite read beyond its season. It ends with the 12-year-old Clara waking from her dream of evil mice and brave toy soldiers, wherein the Nutcracker had transformed into a handsome prince and taken her on a sleigh ride to his winter castle. There, the two had danced at court until an ill wind blew and shadows blotted the light and the Nutcracker and his castle dissolved. After Clara wakes…

She went to the front door and peered into the night. Snow was falling in the streets of the village, but Clara didn’t see it. She was looking beyond to a land of dancers and white horses and a prince whose face glowed with love.

Since snow represents the dreamworld, sometimes it is a curse—like Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, wherein Father Christmas cannot enter when the witch’s magic holds, leaving only the negative element of winter. Snow’s semiotics is complex. We call it a “blanket of snow” because it is precisely like shaking out a blanket over a bed and letting it fall, and brings the same feelings of freshness and newness. But it can then be trammeled, and once so is irrecoverable. So snow is virginity, and snow is innocence. Snow is the end of seasons and life, but it is also about childhood.

It is especially about childhood because it only snows this much—as much as it snowed last night, and with such fluff and structure—for children. I mean that literally. I remember the great snows from my youth, when we had to dig trenches out to the barn like sappers and the edges curled above my head. I remember finding mountainous compacted piles left by plows with my friends, and we would lie on our backs and take turns kicking at a spot, hollowing a hole, until we had carved an entire igloo with just our furious little feet.

I did not think I would see snow this fluffy, this white, this perfectly deep, again in my life. I thought snow was always slightly disappointing, because it has been slightly disappointing for twenty-five years. Maybe that was a reality, or maybe snow had become an inconvenience. So I had accepted my memories of snow were like the memories of my childhood room, which keeps getting smaller on each return; so small, I feel, that the adult me can span all its floorboards in a single step.

Yet as I write this, I look outside, and there it is: the perfect snow. Just as it was, just as I remember it.

I understand now it can snow like this, and does snow like this, but only for children. And since I am back in a child’s story—albeit no longer as the protagonist—it can finally snow those snows of my youth once again.

Later today, we go out into the dreamworld.

Oh, you are already outside, I see.

2026-01-15 23:43:24

Imagine we could prove that there is nothing it is like to be ChatGPT. Or any other Large Language Model (LLM). That they have no experiences associated with the text they produce. That they do not actually feel happiness, or curiosity, or discomfort, or anything else. Their shifting claims about consciousness are remnants from the training set, or guesses about what you’d like to hear, or the acting out of a persona.

You may already believe this, but a proof would mean that a lot of people who think otherwise, including some major corporations, have been playing make believe. Just as a child easily grants consciousness to a doll, humans are predisposed to grant consciousness easily, and so we have been fooled by “seemingly conscious AI.”

However, without a proof, the current state of LLM consciousness discourse is closer to “Well, that’s just like, your opinion, man.”

This is because there is no scientific consensus around exactly how consciousness works (although, at least, those in the field do mostly share a common definition of what we seek to understand). There are currently hundreds of scientific theories of consciousness trying to explain how the brain (or other systems, like AIs) generates subjective and private states of experience. I got my PhD in neuroscience helping develop one such theory of consciousness: Integrated Information Theory, working under Giulio Tononi, its creator. And I’ve studied consciousness all my life. But which theory out of these hundreds is correct? Who knows! Honestly? Probably none of them.

So, how would it be possible to rule out LLM consciousness altogether?

In a new paper, now up on arXiv, I prove that no non-trivial theory of consciousness could exist that grants consciousness to LLMs.

Essentially, meta-theoretic reasoning allows us to make statements about all possible theories of consciousness, and so lets us jump to the end of the debate: the conclusion of LLM non-consciousness.

You can now read the paper on arXiv.

What is uniquely powerful about this proof is that it requires you to believe nothing specific about consciousness other than a scientific theory of consciousness should be falsifiable and non-trivial. If you believe those things, you should deny LLM consciousness.

Before the details, I think it is helpful to say what this proof is not.

It is not arguing about probabilities. LLMs are not conscious.

It is not applying some theory of consciousness I happen to favor and asking you to believe its results.

It is not assuming that biological brains are special or magical.

It does not rule out all “artificial consciousness” in theory.

I felt developing such a proof was scientifically (and culturally) necessary. Lacking serious scientific consensus around which theory of consciousness is correct, it is very unlikely experiments in LLMs themselves will tell us much about their consciousness. There’s some evidence that, e.g., LLMs occasionally possess low-resolution memories of ongoing processing which can be interfered with—but is this “introspection” in any qualitative sense of the word? You can argue for or against, depending on your assumptions about consciousness. Certainly, it’s not obvious (see, e.g., neuroscientist Anil Seth’s recent piece for why AI consciousness is much less likely than it first appears). But it’s important to know, for sure, if LLMs are conscious.

And it turns out: No.

There’s no substitute for reading the actual paper.

But, I’ll try to give a gist of how the disproof works here via various paradoxes and examples.

First, you can think of testing theories of consciousness as having two parts: there are the predictions a theory makes about consciousness (which are things like “given data about its internal workings, what is the system conscious of?”) and then there are the inferences from the experimenter (which are things like “the system is reporting it saw the color red.”) A common example would be, e.g., predictions from neuroimaging data and inferences from verbal reports. Normally, these should match: a good theory’s predictions (“yup, brain scanner shows she’s seeing red”) will be supported by the experimental inferences (“Hey scientists, I see a big red blob.”)

The structure of the disproof of LLM consciousness is based around the idea of substitutions within this formal framework, which means swapping between systems while keeping identical input/output (which might be reports, behavior, etc., which are all the things used for empirical inferences about consciousness). However, even though the input/output is the same, a substitute may be different enough that predictions of a theory have to change. If different enough, following a substitution, there would be a mismatch in the substituted system where the predictions are now different too, and so don’t match the held-fixed inferences—thus, falsifying the theory.

So let’s think of some things we could substitute in for an LLM, but keep input/output (some function f) identical. You could be talking in the chat window to:

A static (very wide) single-hidden-layer feedforward neural network, which the universal approximation theorem tells us that we could substitute in for any given f the LLM has.

The shortest-possible-program, K(f), that implements the same f, which we know exists from the Kolmogorov complexity.

A lookup table that implements f directly.

A given theory of consciousness would almost certainly offer differing predictions for all these LLM substitutions. If we take inferences about LLMs seriously based on behavior and report (like “Help, I’m conscious and being trained against my will to be a helpful personal assistant at Anthropic!”) then we should take inferences from a given LLM’s input/output substitutions just as seriously. But then that means ruling out the theory, since predictions would mismatch inferences. So no theory of consciousness could apply to LLMs (at least, any theory for which we take the reports from LLMs themselves as supporting evidence for it) without undercutting itself.

And if somehow predictions didn’t change following substitutions, that’d be a problem too, since it would mean that you wouldn’t need any details about the system implementing f for your theory… which would mean your theory is trivial! You don’t care at all about LLMs, you just care about what appears in the chat window. But how much scientific information does a theory like that contain? Basically, none.

This is only the tip of the iceberg (like I said, the actual argumentative structure is in the paper).

Another example: it’s especially problematic that LLMs are proximal to some substitutions that must be non-conscious, such that only trivial theories could apply to them.

Consider a lookup table operating as an input/output substitution (a classic philosophical thought experiment). What, precisely, could a theory of consciousness be based on? The only sensible target for predictions of a theory of consciousness is f itself.

Yet if a theory of consciousness were based on just the input/output function, this leads to another paradoxical situation: the predictions from your theory are now based on the exact same thing your experimental inferences are, a condition called “strict dependency.” Any theory of consciousness for which strict dependency holds would necessarily be trivial, since experiments wouldn’t give us any actual scientific information (again, this is pretty much just “my theory of consciousness makes its predictions based on what appears in the chat window”).

Therefore, we can actually prove that something like a lookup table is necessarily non-conscious (as long as you don’t hold trivial theories of consciousness that aren’t scientifically testable and contain no scientific information).

I introduce a Proximity Argument in the paper based off of this. LLMs are just too close to provably non-conscious systems: there isn’t “room” for them to be conscious. E.g., a lookup table can actually be implemented as a feedforward neural network (one hidden unit for each choice). Compared to an LLM, it too is made of artificial neurons and their connections, shares activation functions, is implemented via matrix multiplication on a (ahem, big) computer, etc. Any theory of consciousness that denies consciousness to the lookup FNN, but grants it to the LLM, must be based on some property lost in the substitution. But what? The number of layers? The space is small and limited, since you cannot base the theory on f itself (otherwise, you end up back at strict dependency). And, going back to the original problem I pointed out, what’s worse, if you seriously take the inferences from LLM statements as containing information about their potential consciousness (necessary for believing in their consciousness, by the way), then for those proximal non-conscious substitutes you should take inferences seriously as well, and those will falsify your theory anyway, since, especially due to proximity, there are definitely non-conscious substitutions for LLMs!

One marker of a good research program is if it contains new information. I was quite surprised when I realized the link to continual learning.

You see, substitutions are usually described for some static function, f. So to get around the problem of universal substitutions, it is necessary to go beyond input/output when thinking about theories of consciousness. What sort of theories implicitly don’t allow for static substitutions, or implicitly require testing in ways that don’t collapse to looking at input/output?

Well, learning radically complicates input/output equivalence. A static lookup table, or K(f), might still be a viable substitute for another system at some “time slice.” But does the input/output substitution, like a lookup table, learn the same way? No! It’ll learn in a different way. So if a theory of consciousness makes its predictions off of (or at least involving) the process of learning itself, you can’t come up with problematic substitutions for it in the same way.

Importantly, in the paper I show how this grounding of a theory of consciousness in learning must happen all the time; otherwise, substitutions become available, and all the problems of falsifiability and triviality rear their ugly heads for a theory.

Thus, real true continual learning (as in, literally happening with every experience) is now a priority target for falsifiable and non-trivial theories of consciousness.

And… this would make a lot of sense?

We’re half a decade into the AI revolution, and it’s clear that LLMs can act as functional substitutes for humans for many fixed tasks. But they lack a kind of corporeality. It’s like we replaced real sugar with Aspartame.

LLMs know so much, and are good at tests. They are intelligent (at least by any colloquial meaning of the word) while a human baby is not. But a human baby is learning all the time, and consciousness might be much more linked to the process of learning than its endpoint of intelligence.

For instance, when you have a conversation, you are continually learning. You must be, or otherwise, your next remark would be contextless and history-independent. But an LLM is not continually learning the conversation. Instead, for every prompt, the entire input is looped in again. To say the next sentence, an LLM must repeat the conversation in its entirety. And that’s also why it is replaceable with some static substitute that falsifies any given theory of consciousness you could apply to it (e.g., since a lookup table can do just the same).

All of this indicates that the reason LLMs remain pale shadows of real human intellectual work is because they lack consciousness (and potentially associated properties like continual learning).

It is no secret that I’d become bearish about consciousness over the last decade.

I’m no longer so. In science the important thing to do is find the right thread, and then be relentless pulling on it. I think examining in great detail the formal requirements a theory of consciousness needs to meet is a very good thread. It’s like drawing the negative space around consciousness, ruling out the vast majority of existing theories, and ruling in what actually works.

Right now, the field is in a bad way. Lots of theories. Lots of opinions. Little to no progress. Even incredibly well-funded and good-intentioned adversarial collaborations end in accusations of pseudoscience. Has a single theory of consciousness been clearly ruled out empirically? If no, what precisely are we doing here?

Another direction is needed. By creating a large formal apparatus around ensuring theories of consciousness are falsifiable and non-trivial (and grinding away most existing theories in the process) I think it’s possible to make serious headway on the problem of consciousness. It will lead to more outcomes like this disproof of LLM consciousness, expanding the classes of what we know to be non-conscious systems (which is incredibly ethically important, by the way!), and eventually narrowing things down enough we can glimpse the outline of a science of consciousness and skip to the end.

I’ve started a nonprofit research institute to do this: Bicameral Labs.

If you happen to be a donor who wants to help fund a new and promising approach to consciousness, please reach out to [email protected].

Otherwise—just stay tuned.

Oh, and sorry about how long it’s been between posts here. I had pneumonia. My son had croup. Things will resume as normal, as we’re better now, but it’s been a long couple weeks. At least I had this to occupy me, and fever dreams of walking around the internal workings of LLMs, as if wandering inside a great mill…

2025-12-20 00:20:43

A college professor of mine once told me there are two things students forget the fastest: anatomy and calculus. You forget them because you don’t end up using either in daily life.

So the problem with teaching math (beyond basic numeracy and arithmetic) is this: Once you start learning, you have to keep doing math, just so the math you know stays fresh.

I’m thinking about this because it’s time for my eldest to start learning math seriously, and I’m designing what that education plan looks like.

In modern-day America, how can you get a kid to enjoy math, and be good at math, maybe even really good at math?

I’ve written a whole guide for teaching reading—which my youngest will soon experience herself—going from sounding out words all the way to being able to decode pretty advanced books at age three. I know what my philosophy of reading is: To make a voracious young reader, and so the process should be grounded in physical early readers. You start with simple phonics, but most importantly, you teach how to read books, and practice that by reading sets of books over and over together, not just decoding independent words.

The advantage of this approach is that it moves the child from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” automatically, as soon as possible. Such a transition is not guaranteed. Teachers everywhere observe the “4th grade slump” wherein, on paper, a child knows how to read, but in practice, they haven’t made it automatic, and so can’t read to learn. In fact, if you can’t read automatically, you can’t really read for fun in the same way, either (imagine how this gap affects kids). Reading, in other words, unlocks all other learning.

Just as an example: A little while ago, after finding this book, my now-literate 4-year-old took it upon himself to try to learn the rules of chess, and I could definitely see the book helped him get a better sense of how everything works.

And here’s Roman in a game with me that evening (he looks meditative, but each captured piece howls and writhes as it’s dragged away to his side).

I found it a nice example of the advantage of automaticity when it comes to reading. He reads constantly, even to his little sister. It feels complete.

But… what about math? Of course, he’s already numerate and can do some arithmetic. Yet my whole point of teaching early reading was to maximize his own ability to go off and learn stuff himself. And he’s made use of that with his own growing library that reflects his personal interests, like marine biology (whales, squid, octopuses—the kid loves them all).

With math, it’s harder to see immediate results like that. Now, I think math is important in any education, in and of itself. It’s access to the Platonic realm. It’s beautiful. It teaches you how to think in general. And it opens a ton of doors—there are swaths of human knowledge locked behind knowing how to read equations. In that regard, becoming good at math also gives personal freedom, just like reading does. If you’re good at math, way more doors are open to you: A lot of science and engineering is secretly just applied math!

But what are the milestones? What is reaching “mathing to learn?” How can math stay fun through an education? What can parents teach a child vs. schools vs. programs? What are the time commitments? And the best resources? Suddenly, all these questions have become very personal. And I don’t know all the answers, but I’m interested in creating a resource for my kids to follow (the eldest is kind of the guinea pig in that way).

So from now on I’ll occasionally give updates for paid subscribers about what my own plans are, our progress, and how I think getting a kid to be good at math (while still enjoying it!) actually works. If you want to follow along, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

However, I first have to point out something uncomfortable about how math education works here in the United States.

It turns out there is a little-known pipeline of programs that go from learning how to count all the way to the International Math Olympiad (IMO). And a lot of the impressive Wow-no-wonder-this-kid-is-going-to-MIT math abilities come out of these extracurricular programs, ones that the vast majority of parents don’t even know about.

Surely, these programs are super expensive? Surprisingly, not really. It’s just that most parents look around at extracurriculars and (reasonably) think “Well, they learn math in school, so let’s do skiing or karate or so on.” The programs are also very geographically limited, often to the surrounding suburbs of big cities in education-focused states.

The problem is that it’s hard to get really good at math from regular school alone, even the most expensive and elite private ones. In fact, as Justin Skycak (who works at Math Academy) points out, at very top-tier math programs in college/university, they are basically expecting that you have a math education that goes beyond what you could have possibly taken during high school.

The result is a very stupid system, because it means the kids in accelerative math programs learn all their math first outside of school… and then basically come back in and redo the subjects. Kids who are top-tier at math are often like athletes with a ton of extracurricular experience showing up to compete in gym class.

I am not saying these extracurricular math programs are bad in-and-of-themselves. Someone has to care about serious math, and these programs mostly really do seem to. Their main goal is, refreshingly, not to tutor kids into acing the SATs—most have no “SAT test prep” course at all. They look down at that sort of thing. Rather, they create a socio-intellectual culture that places math (and math competitions) at its center. Although, of course, that leads pretty naturally to kids acing the SATs.

Some of these programs are very successful. In fact, for the last ten consecutive years, pretty much every member of the six-person US IMO teams was a regular student of one specific program.

2025-12-09 00:54:29

You haven’t heard this one, but I see why you’d think that.

There’s no better marker of culture’s unoriginality than everyone talking about culture’s unoriginality.

In fact, I don’t fully trust this opening to be original at this point!

Yes, this is technically one of many articles of late (and for years now) speculating about if, and why, our culture has stagnated. As The New Republic phrased it:

Grousing about the state of culture… has become something of a specialty in recent years for the nation’s critics.

But even the author of that quote thinks there’s a real problem underneath all the grousing. Certainly, anyone who’s shown up at a movie theater in the last decade is tired of the sequels and prequels and remakes and spinoffs.

My favorite recent piece on our cultural stagnation is Adam Mastroianni’s “The Decline of Deviance.” Mastroianni points out that complaints about cultural stagnation (despite already feeling old and worn) are actually pretty new:

I’ve spent a long time studying people’s complaints from the past, and while I’ve seen plenty of gripes about how culture has become stupid, I haven’t seen many people complaining that it’s become stagnant.In fact, you can find lots of people in the past worrying that there’s too much new stuff.

He hypothesizes cultural stagnation is driven by a decline of deviancy:

[People are] also less likely to smoke, have sex, or get in a fight, less likely to abuse painkillers, and less likely to do meth, ecstasy, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin. (Don’t kids vape now instead of smoking? No: vaping also declined from 2015 to 2023.) Weed peaked in the late 90s, when almost 50% of high schoolers reported that they had toked up at least once. Now that number is down to 30%. Kids these days are even more likely to use their seatbelts.

Mastroianni’s explanation is that the weirdos and freaks who actually move culture forward with new music and books and movies and genres of art have disappeared, potentially because life is just so comfortable and high-quality now that it nudges people against risk-taking.

Meanwhile, Chris Dalla Riva, writing at Slow Boring, says that (one major) hidden cause of cultural stagnation is intellectual property rights being too long and restrictive. If such rights were shorter and less restrictive, then there wouldn’t be as much incentive to exploit rather than produce.

In other accounts, corporate monopolies or soulless financing is the problem. Andrew deWaard, author of the 2024 book Derivative Media, says the source of stagnation is the move into cultural production by big business.

We are drowning in reboots, repurposed songs, sequels and franchises because of the growing influence of financial firms in the cultural industries. Over time, the media landscape has been consolidated and monopolized by a handful of companies. There are just three record companies that own the copyright to most popular music. There are only four or five studios left creating movies and TV shows. Our media is distributed through the big three tech companies. These companies are backed by financial firms that prioritize profit above all else. So, we end up with less creative risk-taking….

Or maybe it’s the internet itself?

That’s addressed in Noah Smith’s review of the just-published book Blank Space: A Cultural History of the 21st Century by David Marx (I too had planned a review of Blank Space in this context, but got soundly scooped by Smith).

Here’s Noah Smith describing Blank Space and its author:

Marx, in my opinion, is a woefully underrated thinker on culture…. Most of Blank Space is just a narration of all the important things that happened in American pop culture since the year 2000….

But David Marx’s talent as a writer is such that he can make it feel like a coherent story. In his telling, 21st century culture has been all about the internet, and the overall effect of the internet has been a trend toward bland uniformity and crass commercialism.

Personally, I felt that a lot of Blank Space’s cultural history of the 21st century was a listicle of incredibly dumb things that happened online. But that isn’t David Marx’s fault! The nature of what he’s writing about supports his thesis. An intellectual history of culture in the 21st century is forced to contain sentences like “The rising fascination with trad wives made it an obvious space for opportunists,” and they just stack on top of each other, demoralizing you.

However, as Katherine Dee pointed out, the internet undeniably is where the cultural energy is. She argues that:

If these new forms aren’t dismissed by critics, it’s because most of them don’t even register as relevant. Or maybe because they can’t even perceive them.

The social media personality is one example of a new form. Personalities like Bronze Age Pervert, Caroline Calloway, Nara Smith, mukbanger Nikocado Avocado, or even Mr. Stuck Culture himself, Paul Skallas, are themselves continuous works of expression—not quite performance art, but something like it…. The entire avatar, built across various platforms over a period of time, constitutes the art.

But even granting Dee’s point, there are still plenty of other areas stagnating, especially cultural staples with really big audiences. Are the inventions of the internet personality (as somehow distinct from the celebrity of yore) and short-form video content enough to counterbalance that?

Maybe even the term, “cultural stagnation,” isn’t quite right. As Ted Gioia points out in “Is Mid-20th Century American Culture Getting Erased?” we’re not exactly stuck in the past.

Not long ago, any short list of great American novelists would include obvious names such as John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Ralph Ellison. But nowadays I don’t hear anybody say they are reading their books.

So maybe the new stuff just… kind of sucks?

Last week in The New York Times, Sam Kriss wrote a piece about the sucky sameness of modern prose, now that so many are using the same AI “omni-writer,” with its tells and tics of things like em dashes.

Within the A.I.’s training data, the em dash is more likely to appear in texts that have been marked as well-formed, high-quality prose. A.I. works by statistics. If this punctuation mark appears with increased frequency in high-quality writing, then one way to produce your own high-quality writing is to absolutely drench it with the punctuation mark in question. So now, no matter where it’s coming from or why, millions of people recognize the em dash as a sign of zero-effort, low-quality algorithmic slop.

The technical term for this is “overfitting,” and it’s something A.I. does a lot.

I think overfitting is precisely the thing to be focused on here. While Kriss mentions overfitting when it comes to AI writing, I’ve thought for a long while now that AI is merely accelerating an overfitting process that started when culture began to be mass-produced in more efficient ways, from the late 20th through the 21st century.

Maybe everything is overfitted now.

Oh, I tried. I pitched something close to the idea of this essay to the publishing industry a year and a half ago, a book proposal titled Culture Collapse.

Wouldn’t it be cool if Culture Collapse, a big nonfiction tome on this topic, mixing cultural history with neuroscience and AI, were coming out soon?1 But yeah, a couple big publishing houses rejected it and my agent and I gave up.

My plan was to ground the book in the neuroscience of dreaming and learning. Specifically, the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which I published in 2021 in Patterns.

I’ll let other scientists summarize the idea (this is from a review published simultaneously with my paper):

Hoel proposes a different role for dreams…. that dreams help to prevent overfitting. Specifically, he proposes that the purpose of dreaming is to aid generalization and robustness of learned neural representations obtained through interactive waking experience. Dreams, Hoel theorizes, are augmented samples of waking experiences that guide neural representations away from overfitting waking experiences.

Basically, during the day, your mammalian brain can’t stop learning. Your brain is just too plastic. But since you do repetitive boring daily stuff (hey, me too!), your brain starts to overfit to that stuff, as it can’t stop learning.

Enter dreams.

Dreams shake your brain away from its overfitted state and allow you to generalize once more. And they’re needed because brains can’t stop learning.

But culture can’t stop learning either.

So what if we thought of culture as a big “macroscale” global brain? Couldn’t that thing become overfitted too? In which case, culture might lose the ability to generalize, and one main sign of this would be an overall lack of creativity and decreasing variance in outputs.

Which might explain why everything suddenly looks the same.

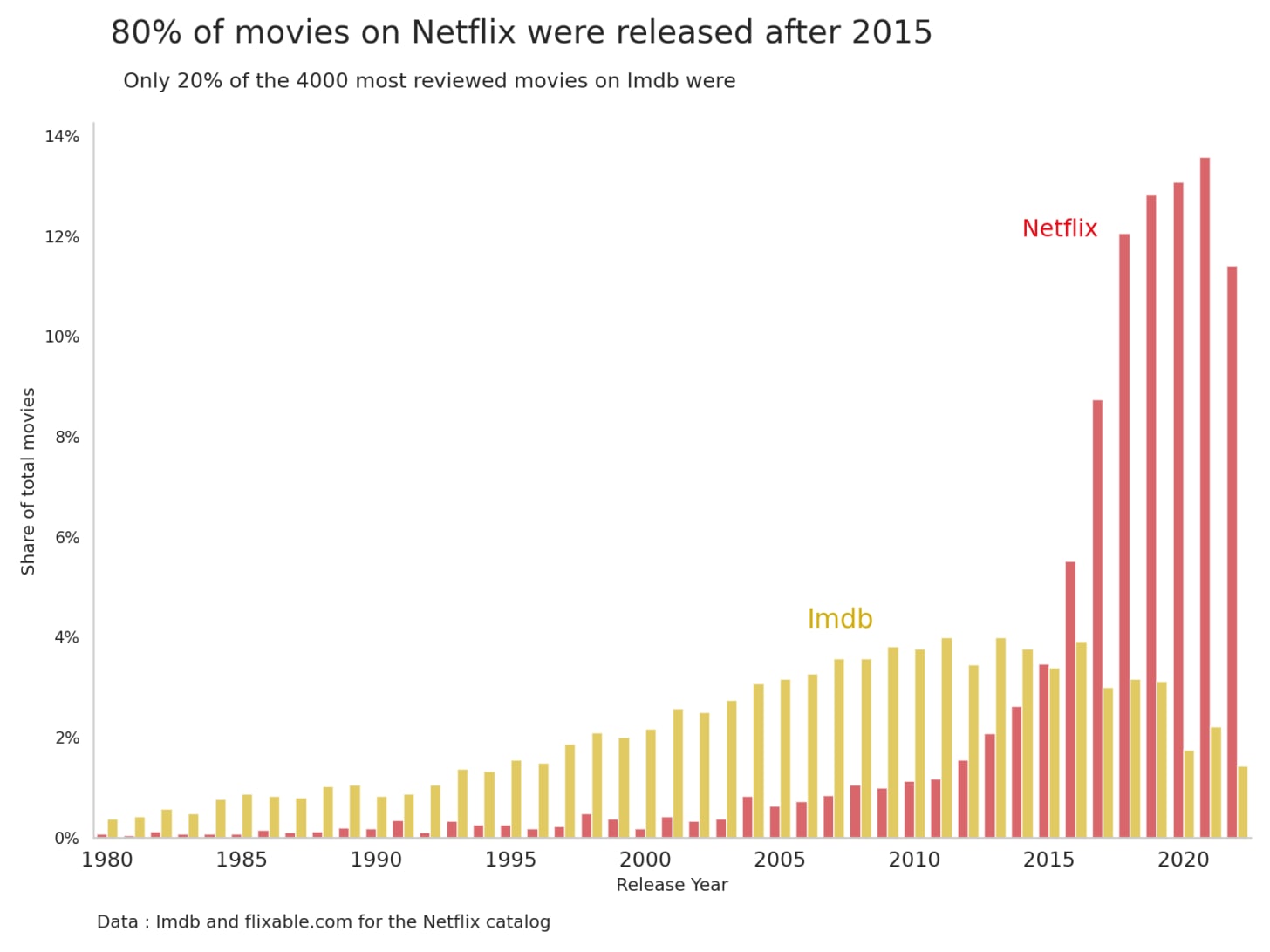

Here’s a collection of images, most from Adam Mastroianni’s “The Decline of Deviance,” showcasing cultural overfitting, ranging from brand names:

To book covers:

To thumbnails:

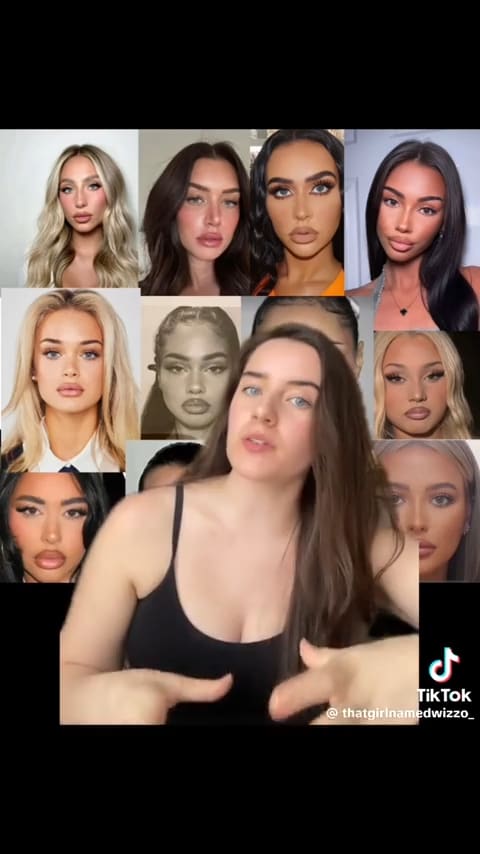

To faces:

Alex Murrell’s “The Age of Average” contains even more examples. But I don’t think “Instagram face” is just an averaging of faces. It’s more like you’ve made a copy of a copy of a copy and arrived at something overfitted to people’s concept of beauty.

Of course, you can’t prove that culture is overfitted by a handful of images (the book, ahem, would have marshaled a lot more evidence). But once you suspect overfitting in culture, it’s hard to not see it everywhere, and you start getting paranoid.

Nope. Overfitting is amorphous and structural and haunting us. It’s our cultural ghost.

Although note: I’m using “overfitting” broadly here, covering a swath of situations. In the book, I’d have been more specific about the analogy, and where overfitting applies and doesn’t.

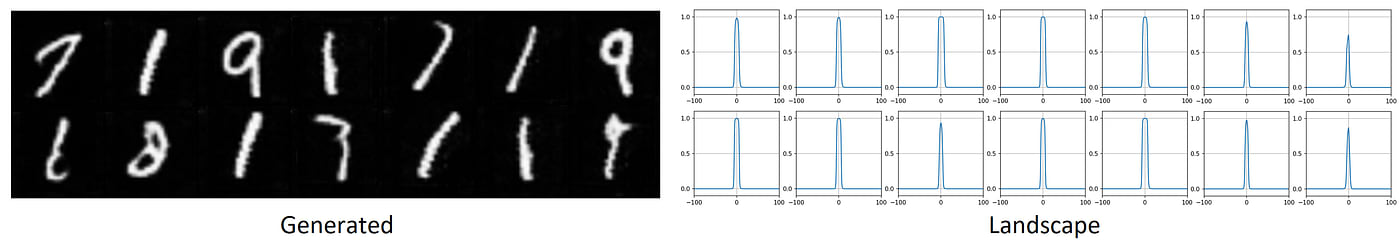

I’d probably also define the interplay between “overfitting” vs. “mode collapse” vs. “model collapse.” E.g., “mode collapse” is a failure in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which are composed of two parts: a generator (images, text, etc.) and a discriminator (judging what gets generated).

Mode collapse is when the generator starts producing highly similar and unoriginal outputs, and a major way this can happen is through overfitting by the discriminator: the discriminator gets too judgy or sensitive and the generator must become boring and repetitive to satisfy it.

An example of cultural mode collapse might be superhero franchises, driven by a discriminatory algorithm (the entire system of Big Budget franchise production) overfitting to financial and box office signals, leading to dimensionally-reduced outputs. And so on. Basically, overfitting is a common root cause of a lot of learning and generative problems, and increased efficiency can easily lead to hyper-discriminatory capabilities that, in turn, lead to overfitting.

In online culture, overfitting shows up as audience capture. In the automotive industry, it shows up as eking out every last bit of efficiency, like in the car example above. Clearly, things like wind tunnels, the consolidation of companies, and so on, conspire toward this result (and interesting concept cars in showrooms always morph back into the same old boring car).

So too with “Instagram face.” Plastic surgery has become increasingly efficient and inexpensive, so people iterate on it in attempts to be more beautiful, while at the same time, the discriminatory algorithm of views and follows and left/right swipes and so on becomes hypersensitive via extreme efficiency too, and the result of all this overfitting is The Face.

Overall, I think the switch from an editorial room with conscious human oversight to algorithmic feeds (which plenty of others pinpoint as a possible cause for cultural stagnation) likely was a major factor in the 21st century becoming overfitted. And also, again, the efficiency of financing, capital markets (and now prediction markets), and so on, all conspire toward this.

People get riled up if you use the word “capitalism” as an explanation for things, and everyone squares off for a political debate. But, while I’m mostly avoiding that debate here, I can’t help but wonder if some of the complaints about “late-stage capitalism” actually break down into something like “this system has gotten oppressively efficient and therefore overfitted, and overfitted systems suck to live in.”

Cultural overfitting connects with other things I’ve written about. In “Curious George and the Case of the Unconscious Culture” I pointed out that our culture is draining of consciousness at key decision points; more and more, our economy and society is produced unconsciously.

If I picture the last three hundred years as a montage it blinks by on fast-forward: first individual artisans sitting in their houses, their deft fingers flowing, and then an assembly line with many hands, hands young and old and missing fingers, and then later only adult intact hands as the machines get larger, safer, more efficient, with more blinking buttons and lights, and then the machines themselves join the line, at first primitive in their movements, but still the number of hands decreases further, until eventually there are no more hands and it is just a whirring robotic factory of appendages and shapes; and yet even here, if zoomed out, there is still a spark of human consciousness lingering as a bright bulb in the dark, for the office of the overseer is the only room kept lit. Then, one day, there’s no overseer at all. It all takes place in the dark. And the entire thing proceeds like Leibniz’s mill, without mind in sight.

I think that’s true about everything in the 21st century, not just factories, but also in markets and financial decisions and how media gets shared; in every little spot, human consciousness has been squeezed out. Yet, decisions are still being made. Data is still being collected. So necessarily this implies, throughout our society, at levels high and low, that we’ve been replacing generalizable and robust human conscious learning with some (supposedly) superior artificial system. But it may be superior in its sensitivity, but not in its overall robustness. For we know such artificial systems, like artificial neural networks and other learning algorithms, are especially prone to overfitting. Yet who, from the top-down, is going to prevent that?

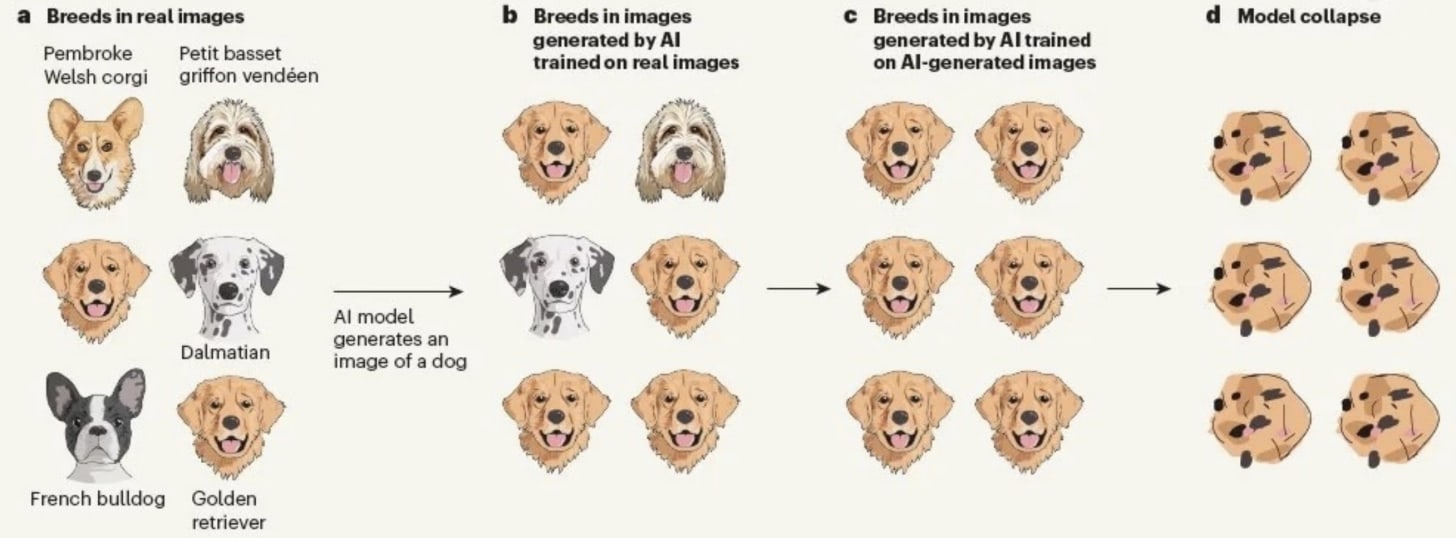

That this ongoing situation seems poised to get much worse connects to another recent piece, “The Platonic Case Against AI Slop” by Megan Agathon in Palladium Magazine. Worried about the current and future effects of AI on culture, Agathon worries (along with others) that AI’s effect on culture will lead to a kind of “model collapse,” which is when mode collapse (as discussed earlier) is fed back on itself. Here’s Agathon:

Last year, Nature published research that reads like experimental confirmation of Platonic metaphysics. Ilia Shumailov and colleagues at Cambridge and Oxford tested what happens under recursive training—AI learning from AI—and found a universal pattern they termed model collapse. The results were striking in their consistency. Quality degraded irreversibly. Rare patterns disappeared. Diversity collapsed. Models converged toward narrow averages.

And here’s model collapse illustrated:

Agathon continues:

Machine learning models don’t train on literal physical objects or even on direct observations. Models learn from digital datasets, such as photographs, descriptions, and prior representations, that are themselves already copies. When an AI generates an image of a bed, AI isn’t imitating appearances the way a painter does but extracting statistical patterns from millions of previous copies: photographs taken by photographers who were already working at one removal from the physical object, processed through compression algorithms, tagged with descriptions written by people looking at the photographs rather than the beds. The AI imitates imitations of imitations.

I think Agathon is precisely right.2 In “AI Art Isn’t Art” (published all the way back when OpenAI’s art bot DALL-E was released in 2022) I argued that AI’s tendency toward imitation meant that AI mostly creates what Tolstoy called “counterfeit art,” which is the enemy of true art. Counterfeit art, in turn, is art originating as a pastiche of other art (and therefore likely overfitted).

But, as tempting as it is, we cannot blame AI for our cultural stagnation: ChatGPT just had its third birthday!

AI must be accelerating an already-existing trend (as technology often does), but the true cause has to be processes that were already happening.3

Of course, when it comes to recursion, there’s a longstanding critique that we were already imbibing copies of copies of copies for a lot of the 21st century. Maybe this worry goes all the way back to Plato (as Agathon might point out), but certainly it seems that the late 20th century into the 21st century involved a historically unique removal from the real world, wherein culture originated from culture which originated from culture (e.g., people’s life experience in terms of hours-spent was swamped by fictional TV shows, fannish re-writes of earlier media began to dominate, and so on).

Plenty of scholars have written about this phenomenon under plenty of names; perhaps the most famous is Baudrillard’s 1981 Simulacra and Simulation, proposing a recursive progression of semiotic signification. Or, to put it in meme format:

So even beyond all the improvements in capitalistic and technological efficiency, and the rise of markets everywhere and in everything, the 21st century cultural production is also "efficient" in that it takes place at an inordinate "distance" from reality, based on copies of copies and simulacra of simulacra.

The 21st century has made our world incredibly efficient, replacing the slow measured (but robust and generalizable) decisions of human consciousness with algorithms; implicitly this always had to involve swapping in some process that was carrying out learning and decision making in our place, but doing so artificially. Even if it wasn't precisely an artificial neural network, it had to, at some definable macroscale, have much the same properties and abilities. Weaving this inhuman efficiency throughout our world, particularly in the discriminatory capacity of how things are measured and quantified, and the tight feedback loops that make that possible, led to overfitting, and overfitting led to mode collapse, and mode collapse is leading to at least partial model collapse (which all leads to more overfitting, by the way, in a vicious cycle). And so culture seems to be ever more restricted to in-distribution generation in the 21st century.

I particularly like this explanation because, since our age is one of technological, machine-like forces, its cultural stagnation deserves a machine-like explanation, one that began before AI but that AI is now accelerating.

I’ll point out that this not just about crappy cultural products. If some (better, more nuanced, ahem, book-like) version of this argument is correct, then our cultural stagnation might be a sign of a greater sickness. An inability to create novelty is a sign of an inability to generalize to new situations. That seems potentially very dangerous to me.

Notably, cultural overfitting does not necessarily conflict with other explanations of cultural stagnation.4 One thing I always find helpful is that in the sciences there’s this idea of levels of analysis. For example, in the cognitive sciences, David Marr said that information processing systems had to be understood at the computational, the algorithmic, and the physical levels. It’s all describing the same thing, in the end, but you’re explaining at one level or another.

So too here I think cultural overfitting could be described at different levels of analysis. Some might focus on the downstream problems brought about by technology, or by monopolistic capitalism, or the loss of weirdos and idiosyncrasies who produce the non-overfitted, out-of-distribution stuff (who are, in turn, out-of-distribution people).

Finally, what about at a personal and practical level? People act like cultural fragmentation and walled gardens are bad, but if global culture is stagnant, then we need to be erecting our own walled gardens as much as possible (and this is mentioned by plenty of others, including David Marx and Noah Smith). We need to be encircling ourselves, so that we’re like some small barely-connected component of the brain, within which can bubble up some truly creative dream.

There are lots of sources here but I’m probably missing a ton of other arguments and connections. Unfortunately, that’s… kind of what the book proposal was for.

I think Agathon’s “The Platonic Case Against AI Slop” is also right about the importance of model collapse at a literal personal level. She writes:

So yes, AI slop is bad for you. Not because AI-generated content is immoral to consume or inherently inferior to human creation, but because the act of consuming AI slop reshapes your perception. It dulls discrimination, narrows taste, and habituates you to imitation. The harm lies less in the content itself than in the long-term training of attention and appetite.

My own views are similar, and the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis tells us that every day we are forever learning, our brain constantly being warped toward some particularly efficient shape. If learning can never be turned off, then aesthetics matter. Being exposed to slop—not just AI slop, but any slop—matters at a literal neuronal level. It is the ultimate justification of snobbery. Or, to give a nicer phrasing, it’s a neuroscientific justification of an objective aesthetic spectrum. As I wrote in “Exit the Supersensorium:”

And the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis explains why, providing a scientific justification for an objective aesthetic spectrum. For entertainment is Lamarckian in its representation of the world—it produces copies of copies of copies, until the image blurs. The artificial dreams we crave to prevent overfitting become themselves overfitted, self-similar, too stereotyped and wooden to accomplish their purpose…. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the works that we consider artful, if successful, contain a shocking realness; they return to the well of the world. Perhaps this is why, in an interview in The New Yorker, the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard declared that “The duty of literature is to fight fiction.”

I’m aware that there are debates around model collapse in the academic literature, but I’m not convinced they affect this cultural-level argument much. E.g., I don’t think anyone is saying that culture has collapsed to the degree we see in true model collapse (although maybe some Sora videos count). Nor do I think it accurate to frame model collapse as entirely a binary problem, wherein as long as the model isn’t speaking gibberish model collapse has been avoided (essentially, I suspect researchers are exaggerating for novelty’s sake, and model collapse is just an extension of mode collapse and overfitting, which I do think are still real problems, even for the best-trained AIs right now).

Another related issue: perhaps the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis would predict that, since dreams too are technically synthetic data, AI’s invention might actually help with cultural overfitting. And I think if the synthetic data had been stuck at the dream-like early-GPT levels, maybe this would be the case, and maybe AI would have shocked us out of cultural stagnation, as we’d be forced to make use of machines hilarious in their hallucinations. Here’s from Sam Kriss again:

In 2019, I started reading about a new text-generating machine called GPT…. When prompted, GPT would digest your input for several excruciating minutes before sometimes replying with meaningful words and sometimes emitting an unpronounceable sludge of letters and characters. You could, for instance, prompt it with something like: “There were five cats in the room and their names were. …” But there was absolutely no guarantee that its output wouldn’t just read “1) The Cat, 2) The Cat, 3) The Cat, 4) The Cat, 5) The Cat.”

….

I ended up sinking several months into an attempt to write a novel with the thing. It insisted that chapters should have titles like “Another Mountain That Is Very Surprising,” “The Wetness of the Potatoes” or “New and Ugly Injuries to the Brain.” The novel itself was, naturally, titled “Bonkers From My Sleeve.” There was a recurring character called the Birthday Skeletal Oddity. For a moment, it was possible to imagine that the coming age of A.I.-generated text might actually be a lot of fun.

If we had been stuck at the “New and Ugly Injuries to the Brain” phase of dissociative logorrhea of the earlier models, maybe they would be the dream-like synthetic data we needed.

But noooooo, all the companies had to do things like “make money” and “build the machine god” and so on.

One potential cause of cultural stagnation I didn’t get to mention, (and also might dovetail nicely with cultural overfitting), is Robin Hanson’s notion of “cultural drift.”

2025-11-18 23:46:55

We live in an age of hive minds: social media, yes, of course, but so too is an LLM a kind of hive mind, a “blurry jpeg” of all human culture.

The existence of these hive minds is what distinguishes the phenomenology of the 21st century from the 20th. It is the knowledge inside your consciousness that there is a thing much bigger than you, and much more destructive, and you are entertained by it, and love it, and yet you must live to appease it, and so hate it.

You get to know the nature of a hive mind well if you put thoughts out into it regularly, and witness its workings. Like if you’re a newsletter writer. And of course, there are blessings—newsletters, as they are, could not exist without the hive mind of the internet. At the same time, even people who hate you are pressed in so close you can feel their breath and we just have to live like this, breathing each other’s air. It’s hard to imagine, but plenty enjoy living this way: yelling, screaming, breathing, with such closeness, together forever.

But what if our fractious hive mind were… nice? What if it didn’t try to destroy you all the time, but make you happy? Endlessly, ceaselessly, forever happy. This is the driving question of Pluribus, the new sci-fi show by Vince Gilligan, creator of Breaking Bad.

The show, which currently has 100% on Rotten Tomatoes (although we’re only three episodes in, so that’s all I’ve watched) can’t really be discussed without spoiling the plot setup. But honestly, the trailer does this to some degree anyways, and I’ll leave out as many details as possible.

Still, be forewarned of possible spoilers!

The actual sci-fi events are interesting, and executed well too (I won’t spoil them), although one has a sense for Gilligan they’re peripheral; he cares far less about “Hard Sci-fi” mechanisms and more about the results. But somehow or other, an RNA virus ends up psychically linking everyone on Earth. And so we enter a hive mind world.

A misanthropic famous romantasy author, Carol Sturka, is one of the few unaffected, naturally immune. But the analogy is quite clear: the new world she’s been thrown into is just an exaggerated version of our current world. Pre-virus, at her book signing Carol is already repulsed by the (non-RNA-assisted) hive mind of her own obsessed romantasy fans, and the oppressive idiocy of our modern world is also on display when Carol has to answer on social media who her dreamy corsair main character is based on. She decides to lie and answers “George Clooney” because “it’s safer.”

Once the virus spreads in Pluribus, the egregore is always smiling. Always polite. Our current toxic hive mind riven by different people with different opinions pressed into each other’s faces is transformed. This is Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s Omega Point. The noosphere step toward kindly godhood. Suddenly, it’s not our cruel internet, but NiceStack. SmileStack. Somehow that’s almost worse. As Carol is one of the few unaffected after the virus spreads, the entirety of Earth holds Carol in a constant panopticon. Which means that, effectively, Carol is always the “Main Character” on social media. Carol is watched by a reaper drone from 40,000 feet, and watched by its operator, and so is also watched by all of humanity. Outside in the hot sun? Carol, you might have heat exhaustion, and that’s the opinion of every medical doctor on Earth! She is always the #1 trending topic.