2025-12-30 01:03:33

Editor’s note: As a new year dawns, reflects on why New Year’s resolutions so often fail, and what might take their place.

The other day, I asked a friend what she wanted to let go of from this year. “Everything,” she said. “Complete self-erasure.” We laughed—at the absurdity of it, and at the thin, uncomfortable filament of truth running through the joke. How often we look back on a year with a prosecutorial eye, tallying what we didn’t finish, the habits we couldn’t break, the person we failed to become. By January, many of us are already exhausted by ourselves, and by the prospect of having to fix ourselves yet again.

I, too, have a tendency toward extremity. Over the years, I’ve subjected myself to all manner of New Year’s overhauls: I will seize the day. I will wake up at dawn to meditate. I will write 1,000 words by lunch. I will swear off sugar, start wearing sunscreen religiously, go to the gym three times a week, and never again sleep with my phone in my bedroom. By this time next year, I will have written a book and emerged calmer and fitter. Also morally superior. These resolutions were often launched simultaneously, as if sheer volume might improve my chances of seeing them through. I always began with zeal. I always burned out.

This all-or-nothing thinking is not a bug of resolutions; it’s the design. Resolutions are outcome-driven and binary: success or failure, repair or ruin. They rely on force and control to produce change. Unsurprisingly, they don’t work very well. Research suggests that most resolutions fail within a month—which means many of us spend the first weeks of the year not renewed but, at best, quietly chastened. At worst, like a complete and total failure.

When I was 24, I made a New Year’s resolution to run a half-marathon while in treatment for leukemia.

The logic, in my mind, was impeccable. A cancer survivor I’d read about in a magazine—a former professional athlete and reality TV star—had run the New York City Marathon shortly before entering the hospital for a second bone marrow transplant. He was a mythic figure in the cancer community, a cancer-lebrity, if you will. I thought, I want to be like him. I was two years into treatment, and unrecognizable to myself. I’d once planned to become a war correspondent, a life defined by motion and urgency; instead, I had spent the years since graduation in hospital rooms, watching my peers accelerate into adulthood.

I wanted the hero’s-journey arc I’d been promised: to emerge from the worst year of my life stronger, braver, somehow better for it. And so I did the sort of swift, deeply flawed math desperation excels at: he’d had two transplants and run 26 miles. I’d had one transplant, so surely I could manage 13.

I believed, naively, that I could simply decide I’m going to do this and that would be enough. What I failed to consider were several small but relevant facts. I was not a former professional athlete. I had never done any distance running. I had not even managed to complete the mandatory mile in high school gym class. I was still receiving maintenance chemotherapy and spending a good deal of my time horizontal.

None of this registered as disqualifying. As I saw it, I had done the only thing that mattered: I had resolved to do it, therefore it was to be. I had just survived a bone marrow transplant, had I not? I had been told, repeatedly, that I was so strong. Somewhere in this reasoning, I began to believe I might be even more prepared than the most determined of healthy marathon runners—confusing declaration with destiny, and wanting very badly for the two to be the same thing.

I jumped in with both feet. I registered for a benefit race, emailed friends and family asking for donations toward my fundraising goal, and signed up for a gym membership I could barely afford. I put a pair of fancy running shoes and a full set of thermal running gear on my credit card. When I put the whole outfit on and went out for my first jog, I asked my mom to take a photo—fist raised triumphantly—which I promptly posted. Announcing it publicly meant there was no way out.

I began to run-walk a single mile. Physically unprepared as I was, it might as well have been the half-marathon itself. I finished limpingly, wrecked with exhaustion. The next day, I hobbled around, wincing with every step. That weekend, I ended up in the emergency room with a hairline fracture in my foot.

My body had filed a formal complaint. The race was off. Case closed.

I look back now on the whole ordeal as comically doomed from the start. At the time, it felt intimate—not just a failed resolution, but an indictment of my capacity for change. For a brief moment, the plan had lifted me out of myself. I had something to train for, something that made the future feel legible again. When it collapsed almost immediately, it didn’t just knock me back to where I’d started. It confirmed my worst fear: that wanting change was itself a liability, another way to set myself up for disappointment.

Eventually, I stopped making resolutions altogether. Not because I stopped wanting change—but because I stopped trying to become someone else. The desire to work on myself never went away. It simply lost its appetite for spectacle. And so, in place of resolutions, I turned toward ritual.

Rituals are gentler than resolutions. Where resolutions chase outcomes, rituals attend to process. Georgia O’Keeffe took a 30-minute walk each morning in the desert, often alone, believing the walking itself was where the work of painting began. Toni Morrison rose at 5, made her coffee, and waited for the sun to appear—or, as she put it, “watched the light come.” Ludwig van Beethoven, also a devotee of coffee, approached the ritual differently, counting out exactly 60 beans for each cup, the number he believed produced the perfect brew. None of this was about efficiency or output. It was about creating the conditions in which the work—and the self doing it—could come into being.

Rather than control, rituals are relational. They create atmosphere. They offer rhythm and containment. Where resolutions depend on willpower—a finite resource, especially in times of illness or uncertainty—rituals build scaffolding. They don’t ask us to muscle through. They anchor us in time, place, and meaning. Rituals are not impressive. That, I’ve come to believe, is one of their chief virtues. They don’t demand overnight transformation. They ask only that we return—to the canvas or the page, to the body, to ourselves—and see what shows up.

Over time, my rituals have taken many forms, some encompassing a day or a week, others a season. Whenever I reach the point in a workday where my brain begins to feel like a baked potato—soft, inert—I turn, every time, to the same 15-minute guided breathwork to reset. Over the summer, my first cup of coffee became a ritual: sitting in the hammock, cup in hand, no phone, no music, just five minutes in my own company before the day made its demands. During the pandemic, some friends and I ended each day with what we optimistically called “cold plunging”—skinny-dipping in a nearby swimming hole—until winter arrived and the water iced over, restoring our common sense.

Alongside these, I turn to another ritual that has shaped my life in subtler, more durable ways: a 30-day journaling project at the start of each year. Not forever. Not flawlessly. No page requirement, no rules, no obligation to sound wise or write well. Sometimes it’s three pages; sometimes it’s a single sentence or a closed-eye drawing of a giraffe. The only instruction is to show up, to take the lapses in stride, to keep going.

One of my great teachers in this manner of working is the designer and educator Michael Bierut, who originated what became known as the 100-Day Project. He didn’t create it as a challenge or a dare. It arose organically in the aftermath of September 11, when he, like many New Yorkers, felt unmoored. Each day for a year, he chose a single image from the newspaper and used it as the basis for a drawing—sometimes lingering on it for hours, other days finishing in a few strokes. “The practice had less to do with the output and more with getting myself in the proper frame of mind,” he told me. Later he refashioned this ritual for a graduate course and invited his students to do one small creative act that they could repeat for 100 days.

People often imagine such projects as feats of endurance, as something to white-knuckle their way through. He never thought of it like that. “If I’d woken up on January 1 facing the sheer cliff of a year’s worth of drawings, I probably would have gone back to bed,” he said. “I just thought, Why don’t I do this today? And then I did it again the next day.”

That’s how rituals work. They steady us. They open us up to possibility without demanding performance. They keep us from the all-or-nothing thinking—from what Michael Bierut described as the sensation of walking a tightrope, peril increasing with each step until you freeze, convinced you’ll never make it across.

That’s what ritual gives me now. Not a guarantee, not an outcome, not a transformation on a deadline, but a means of staying in motion without hardening, to keep my balance without gripping so tightly. In the pages of my journal, I can exist as my messiest, most unedited self. Within the simple container of 30 days, structure makes room for play.

There is no grand reinvention here—only the patient work of showing up, again and again, nudging myself millimeter by millimeter toward the person I’m becoming.

2025-12-24 01:30:02

No doubt you’ve seen your share of gift guides already, but if you’ve run out the clock and are still searching for the perfect thing, we’re here to help. There are plenty of reasons why a subscription makes a great gift—but at this point, the most salient one is that it’s guaranteed to arrive on time.

To help you explore beyond the bounds of your own inbox, we reached out to a few well-read Substackers and asked them to share their favorite subscriptions. We’ve organized their picks around the kind of last-minute gift you might otherwise grab on your way out the door. These Substacks are better.

of Broke but Moisturized, “a slice of life newsletter on beauty and aging, dispatched from American suburbia,” recommends . “It’s like being part of a secret society of people who use salt crystals as deodorant and roast themselves in sauna blankets and have astrologers on speed dial.”

, the cultural commentator and fashion columnist behind , is pulling for ’s . “In a sea of 2s and 3s, Max is—and will always be, quite frankly—the 1. He’s sharp, incisive, aware, prescient, evocative. He knows his shit and he knows how to write about it, two separate skill sets that Venn diagram so perfectly in this newsletter that is honestly a ‘can’t miss’ for me. I feel lucky to have Max’s writing to look forward to each week.”

James Beard Award–winning cookbook author of the tailors her recommendation to well-dressed travelers: “ has exquisite taste in just about everything. Her Substack is chockablock with her takes on places to go, places to stay and eat and see when you get there, people to know about, and, yes, fashion.”

As the editor of SSENSE and the writer behind , a health and wellness newsletter, has several recommendations. “I love a few of the big fashion Substacks, like and ’s The Molehill,” he told us, “but a semi slept-on newsletter that I’ve been loving this year is ’s The Bengal Stripe, which brings a thoughtful, non-snarky approach to menswear coverage that isn’t just recycled advice from a 2012 issue of GQ. To my mind, he’s one of the best-dressed guys anywhere: a curious and genuine enthusiast in a space where clothes are often treated as trends and are, at least by that logic, rendered disposable.”

Journalist, podcaster, and writer of culture newsletter has just the thing for thrifters: by . “Nora does the hard work of sifting through pages and pages of eBay search results on your behalf, assembling a tightly curated list of things you will absolutely want to buy. Plus, I always leave her newsletter with some great ideas for new keywords to search to find hidden gems.”

And , the journalist and writer behind Read Max, offers stylish readers a twist. “ ’s is about furniture, and sometimes also raw milk.”

For the friend who doesn’t need more stuff—but does love to obsess—these picks skew pleasantly niche.

, the writer behind , a newsletter devoted to innovation and delight, has a pick specifically for fans of New York: “For my friends in NYC (or who just happen to love it) I’d gift ’s The Neighborhoods. Every week, Rob, a terrific writer and photographer, profiles a different section of the city based on his own quirky sensibilities. It’s reliably funny and fascinating.”

She doesn’t ignore those beyond the five boroughs, either: “For everyone else, I’d gift ’s , a delightful deep dive into the quotidian. Some of my favorite past issues were dedicated to security envelope patterns, spatula design, prescription labels and the history of binder clips. So much fun!”

writes Experimental History, a narrative examination of people, data, and science, and recommends . “Great historians uncover how history is far stranger and more interesting than we ever expect. Anton Howes is a great historian.” He also suggests The Egg and the Rock by : “This guy wrote the Minecraft End Poem and now he’s rewriting the history of the universe. It’s the most interesting scientific work happening on Substack right now, and I have no idea how it’s going to turn out.”

And several writers turned to the past. Talía Cu recommends for the budding collector. “ has the most beautiful vintage brooch collection!” Max Read took a nostalgic view. “There are thousands of newsletters about AI and only one (as far as I know) about old Sony gadgets.” He and Kyla Scanlon both also recommend , a Substack that offers exactly what the name promises. “What else do you need to know?” Max asks.

And Emily Kirkpatrick looks to the entertainment of yore. “Give the pop culture know-it-all in your life a crash course in the sacred texts of Y2K with a subscription to Nicstalgia. Whether you’re looking for a pop-culture history lesson or are a millennial who just wants to have their memory viciously jogged, is a masterful curator of these early internet archives.”

Dorie Greenspan recommends a classic: ’s . “Anyone who loves food and great writing will appreciate it. Ruth’s career in food is long and splendid, and luckily for us, she’s saved endless memorabilia, including dreamy menus, and she remembers all the delicious details.”

Emily Kirkpatrick is also in it for the story, which is why she recommends Eat Your Feelings by . “A lot of newsletters will give you a recipe. But how many newsletters will give you a recipe alongside a story about a threesome and some heartwarming marital advice? That’s the beauty of Eat Your Feelings.”

Both Kyla Scanlon and Max Read recommend a boozy favorite: James Beard Award–winning author ’s . Max recommends it for “the cocktail recipes and liquor recommendations, but especially for the yearly three-part gift guide, which alerts me to all kinds of mail-order American cheese and candy treasures and which I refer to year-round for thank-you presents.” (We have chosen to overlook this brazen gift guide Trojan horse.)

Talía Cu, a fashion journalist, educator, and illustrator who writes Latin Zine by Talia Cu, recommends by , “a wonderful archive for learning how to make Mexican conchas or fermented tacos, created by a sourdough expert.”

, the author and illustrator behind ¡Hola Papi!, a Substack that dissects culture, has a rec for the friend who loves to eat out but is trying to cook more in the new year. “The Secret Ingredient is my foodstack go-to, for one reason: has great taste in restaurants, and his recipes are often copycats of those restaurants’ best dishes. For example, the squash bread at San Francisco’s Quince, which I would like delivered to my home weekly but, sadly, cannot afford to do so (yet). If you’re a foodie, you’ll probably see one of your favorite restaurants on his page and, if you’re lucky, a recipe for your favorite menu item.”

John Paul Brammer is a fan of . “For me, when it comes to pop culture, there is only Hunter Harris at . I wish I had some undiscovered gem to include here, but Hunter is the only source I need on this front. It’s like she knows what I want to talk about before I even know what I want to talk about, like Lily Allen’s ‘West End Girl,’ aka ‘Innit Lemonade.’ Keep an eye on this young woman, I think her Substack’s going places!”

Chris Gayomali recommends by . “Deez Links is where I get 69% of my news these days, unfortunately. Delia is one of those twisted geniuses whose brain never seems to get scrambled even as she’s scraping from the most rat-infested corners of the internet. Her ability to neatly synthesize all these disparate threads about people I often find noxious is a gift that I would not wish on anyone.”

Talía Cu recommends , for “all things pop culture, delivered with a snarky and witty perspective.” Meanwhile, for Max Read, “no one is a better or funnier gossip columnist than [of Gossip Time].”

Dorie Greenspan recommends turning to an expert. “’s is definitely the Substack for this obsessive. The force behind bringing Vanity Fair back to life and shaking up The New Yorker, Brown is supersmart, fearless, and a terrific writer. Fresh Hell covers politics and news, but also pop culture and, well, everything that catches her eye and tickles her brain. Brown could write about watching paint dry and I’d want to read her.” Emily Kirkpatrick agrees: “ has a way of delivering the news that makes you feel like a close friend just called to dish up some hot gossip.”

Skip the book they’ve probably already read. These recommendations run the gamut from the analytical to the literary, but all are opinionated, rigorous, and thoughtful.

, who writes , a newsletter about politics, tech, culture, and media, recommends : “It began as primarily a literature review magazine but is evolving to become a veritable general culture magazine. As editor-in-chief has said, a person can have only so many paid subscriptions; why not make one of them a publication that gives you many writers, some world-renowned, some up-and-coming like the Miami miracle ?”

writes the Substack and translates ancient Chinese poetry in . He recommends by : “A charming, no-pressure newsletter where you get to read great books with Robert. I love how he keeps it casual but not shallow.”

For those interested in economic history, Max Read recommends ’s for a “thorough and approachable review of economic history texts. His overview of the medieval-history scholar Chris Wickham’s body of work (and the larger arguments and issues through which Wickham was working) this year was a model of accessible academic writing.”

Kyla Scanlon recommends , of . “Joey covers macroeconomics with exceptional clarity, and his charts are a work of art. His ability to make complex trends feel understandable and grounded in real-world dynamics is absolutely one of a kind.”

Chris Gayomali recommends going straight to the source: subscribing to a novelist. “I’m such an unapologetic fanboy, but she really is one of the best essayists of our generation. I love how her Substack is a glimpse into a slightly more unhinged (lol) and bloggy version of her print writing: sometimes she’ll bowl you over with a sentence so perfect and nasty in its zags that it feels like a brush with God.”

Emily Kirkpatrick turns to the experts: “ is my love, my life. They have literally never led me astray when it comes to choosing what book I want to read next. Their selections have introduced me to so many books I wouldn’t have read otherwise, and every time I am blown away by the quality of storytelling.”

Max Read and Kyla Scanlon, ever in sync, chose to turn up the charm. They both recommend , where “ and , two of North America’s finest picture book authors, [are] doing wonderful critical reads of their favorite picture books.”

And John Paul Brammer recommends . “You’re gonna want to trust me on this. If you’re looking for book recs you won’t find anywhere else, seek out Harold. He’s criminally underfollowed, but the dude reads. I don’t know where he finds the time to read as much as he does, but when he posts a book rec, I buy that book. Like with Schattenfroh, a recent English translation of a titanic, ambitious German novel that could serve as a blunt weapon in an emergency.”

Happy holidays, and may your procrastination go unnoticed into the new year.

2025-12-20 22:02:27

This week, we’re losing our grip on attention, deciding San Francisco’s fate, reviving 19th-century catchphrases, appreciating Geese, and preparing to catch Sinterklaas when he comes down the chimney.

A note: The Weekender will be on hiatus next week. We’ll be back in your inboxes on Saturday, January 3. Happy holidays!

Remembering Rob Reiner: Following the tragic deaths of Rob Reiner and his wife, Michelle, last weekend, Substackers took to the platform to share the impact Reiner and his films have had on their lives. describes learning to comprehend death as a child thanks in part to Reiner’s film Stand by Me. In , remembers his surprising kindness and humility. wrote about Reiner’s versatility—deftly jumping from mockumentaries to rom-coms to horror to drama—in . In , praises Reiner as having been not just a talented force in Hollywood but a warm one as well. And, in a very on-brand memorial, notes that Reiner was “the reason people care about Katz’s Delicatessen.”

Live from Substack: A variety of Substackers took to the airwaves (webwaves?) this week. In a wide-ranging conversation, comedians and discussed everything from a life in showbiz to the Epstein files. of and of went live to discuss the winners and losers of 2025’s creator economy. And the team behind magazine invited viewers to crash their pitch meeting (and inform editor in chief that he looked like a “gay bear Steve Jobs”).

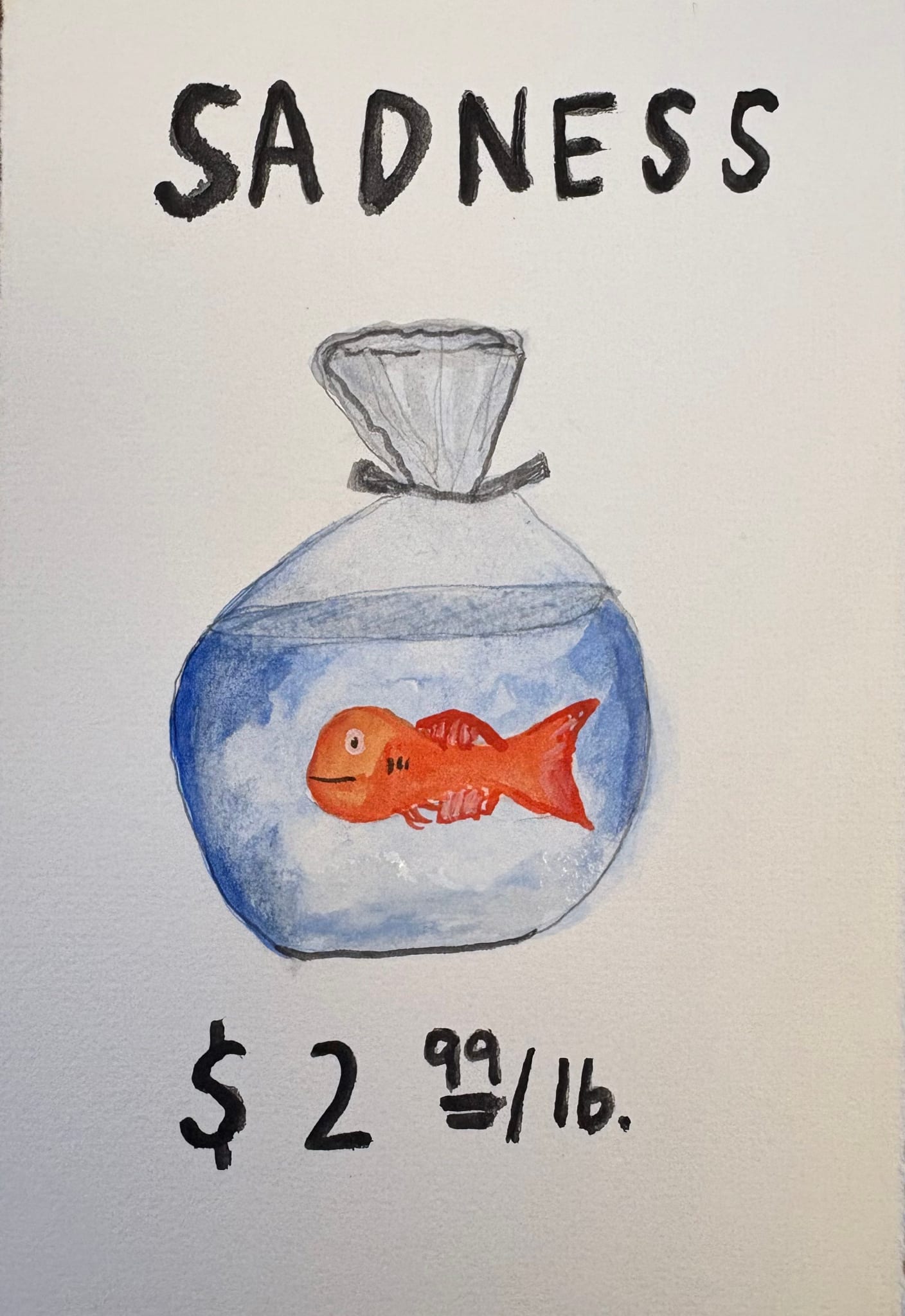

Data doesn’t lie: Believe it or not, the people yearn for more gift guides. According to Substack’s data team, “gift guide” was the most searched-for term this month. A few of the stranger ones we’ve encountered: shared a weird medieval gift guide. The Scoop’s “Grift Guide,” a sort of hater’s guide to 2025, reviewed “grifts” like the New York Times’s Cooking app claiming it takes five minutes to prepare a salmon and the “vaguely sinister” marketing behind Dubai chocolate. Finally, ’s poem “Gift Guide” may not include any helpful links, but it will give you a renewed appreciation for buttered pasta.

In Blackbird Spyplane, Jonah Weiner considers how technology and social media reshape the way we perceive the world.

—Jonah Weiner in

For a time, when I was much more active on Twitter than I am now, I’d find myself, e.g., washing dishes and, without wanting to, thinking about various mundane things in the form of tweets. Some nascent half-kernel of an idea would come to me and, like a hack comedian for whom every banal thing is material, I would immediately start working it over for any and all tweet-like potential.

Maybe there was a tiny bit of dish soap left at the bottom of the bottle, and I considered diluting it with water to get it out more easily and make the bottle last longer. I wouldn’t simply think that. Thanks to Twitter, I’d think something exponentially more inane and annoying, such as, “The masculine urge to water down the dish soap…” or “The two genders [picture of brand-new dish soap vs. picture of old diluted dish soap]…” or “Choose your fighter [same two pictures again]…” or “Wake up, babe, new diluted dish soap just dropped” or “Men will dilute the last millimeter of dish soap rather than go to therapy…” or “No but the way I just diluted the dish soap…”

And so on. Just cycling through a procession of dumb, Twitter-borne phraseologies as they ran through my head, like a radio on the fritz skipping stations. It was a bit like I was idly playing a “brain teaser” puzzle, and a bit like my brains were oozing out of my ears. I’d spent so many hours of so many days reading tweets—encountering other people’s thoughts filtered through the specific character limits and idiomatic conventions of that site—that the seams between my own experiences, thoughts, and tweets began, on some level, to delaminate.

I worry that something analogous has happened in my relationship to looking. The same way that an idea would occur to me and I’d immediately reach for a Stock Twitter Phrase to give it form, whenever I see anything that interests me now, there’s a looming sense in which my phone is there with me, framing and constituting the sight, even if I never post the picture, even if I never look at it again and, weirdest of all, even if don’t take out my phone.

The same way I once conditioned myself to think in tweets, I’ve conditioned myself to see in “posts,” in “grid pics,” in “stories,” in flicks texted to the group chat, in .HEICs, and so on.

This is the underside of what people mean when they describe an extremely “sticky” piece of technology: It can stick to you, like the facehugger from Alien, even when you’re not using it.

Last week, hosted Substack’s Utopia Debates in San Francisco. Over 400 people crowded Bimbo’s 365 Club to see debaters argue about whether we should be creating superbabies and if it’s possible to teach an AI taste. First up: went head-to-head with to decide: Is San Francisco back?

An investigation into Victorian England’s most common slang and catchphrases, which just goes to show: it’s human nature to be annoyingly mimetic.

— in

The mid-19th century was catchphrase heaven. Among them, ‘all serene’, ‘go it you cripples (crutches are cheap)!’, ‘Jim along Josey’, ‘do you see any green in my eye?’ ‘who shot the dog?’ and ‘not in these boots.’ The origins were various, but they sprang mainly from the music hall and from popular plays.

Some, however, had no obvious origin. Such was bender! which appears in 1812 and in effect meant ‘bullshit!’ As defined in James Hardy Vaux’s Vocabulary of the Flash Language, it was ‘an ironical word used in conversation by flash people; as where one party affirms or professes any thing which the other believes to be false or insincere, the latter expresses his incredulity by exclaiming bender! Or, if one asks another to do any act which the latter considers unreasonable or impracticable, he replies, O yes, I’ll do it—bender; meaning, by the addition of the last word, that, in fact, he will do no such thing .’ An ancestor for modernity’s not. By 1835, bender had become over the bender, which apparently reflected a tradition that a declaration made over the (left) elbow, as distinct from not over it, need not be held sacred. The Victorians also used over the left, i.e., pointing with one’s right thumb over one’s left shoulder, implying disbelief.

Charles Mackay’s classic sociological study, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions (1841), was especially interested in the phenomenon of catchphrases. Aside from Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang & Unconventional English (1936-84), which included ‘catchphrases’ in its subtitle, his study represents the great single concentration of the type. Mackay (1814-89) was a poet and journalist, who mixed such posts as that of the Times’ special correspondent during the American Civil War with the writing of song lyrics and of a wide variety of books, many on London or the English countryside. The first volume of Memoirs deals with a variety of such delusions—among them religious relics, witch and tulip manias, the crusades and economic ‘bubbles’—and in the second turns to ‘Popular Follies in Great Cities’.

These, it transpires, are catchphrases, which are ‘repeated with delight, and received with laughter, by men with hard hands and dirty faces—by saucy butcher lads and errand-boys—by loose women—by hackney coachmen, cabriolet drivers, and idle fellows who loiter at the corners of streets.’ He also notes that each one ‘seems applicable to every circumstance, and is the universal answer to every question; in short, it is the favourite slang phrase of the day, a phrase that, while its brief season of popularity lasts, throws a dash of fun and frolicsomeness over the existence of squalid poverty and ill-requited labour, and gives them reason to laugh as well as their more fortunate fellows in a higher stage of society. London is peculiarly fertile in this sort of phrases, which spring up suddenly, no one knows exactly in what spot, and pervade the whole population in a few hours, no one knows how.’

In the prelude to an interview with Cameron Winter that touches on Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and Gregorian chants, Grayson Haver Currin explores what makes Winter’s songs so compelling.

— in

A year ago next week, I paid my friend Brad Cook a holiday visit. In another lifetime, we were longtime roommates who briefly ran a record label together, but we now live on opposite sides of the country, married men with jobs and pets, steadily approaching middle age. We stop by when we can.

I’d been there for just a few minutes when Brad asked if I’d heard Cameron Winter’s solo album, Heavy Metal. When I hemmed and hawed about not entirely loving Geese, he told me he agreed but that, still, I needed to listen. Our pal Jake Lenderman had once felt that way about Geese, but he was now obsessed with Heavy Metal and had recommended it to Brad, who, in turn, recommended it to everyone he encountered. So I followed him into his garage, the same space where he’s made records with Mavis Staples, Waxahatchee, Hurray for the Riff Raff, and Snocaps during the last few years. He played “Nausicaä (Love Will Be Revealed)” so loudly that his dog scampered into the next room. Brad grinned: “Isn’t that the best song you’ve heard all year, Gray?” I relented that he might be right.

A few weeks later, Brad texted to ask me if, when I listened to Heavy Metal, I heard Albert Ayler at all. Maybe that seems like a ridiculous question about a piano-playing singer-songwriter who was just barely drinking age, but I remember the day Brad got an enormous Ayler tattoo on his right arm, so I told him to go on. The music, he suggested, almost always moved in vague opposition to Winter’s voice, like two teams pitted against one another on opposite sides of a ball. Brad said this reminded him of Ayler’s great bands, and, again, I had to relent. We talked about what other phantoms we heard in the music, like strains of the late and overlooked Chris Whitley, and wondered if Winter, then 22, had ever heard any of this old-man music. Probably not?

About eight months later, I was sitting with Winter outside of Dinosaur Coffee in Silver Lake. It was the second in a series of long interviews for a GQ profile of Geese, who were a few weeks away from releasing Getting Killed. At one point, I decided to trot out Brad’s theory, and Winter smiled. “That makes perfect sense,” he said, explaining that he felt that way on 3D Country, too, because he was trying to fight against the perfection of the band with what he called unapproachable vocals. “I like that tension.”

Winter wasn’t putting it on, either. Almost instantly, he started talking about Ayler’s polarizing and brilliant New Grass, the gravity of Sonny Sharrock, and the legacy of Ornette Coleman. I envied him a little in that moment. I am 42, meaning that I’m just at the age when learning about Sharrock or Coleman or Merzbow or Angus MacLise (others who came up that day) meant expensive orders from Forced Exposure at the record store where Brad and I worked, not too terribly long ago. But led by voracious listening interests and a predilection to be a student of sound, Winter had not only streamed so much of this relatively obscure stuff but also learned its lessons, internalizing them as he started to make his own music. Maybe they show up in Heavy Metal or Getting Killed, and maybe they don’t; I still sensed he understood a staggering amount about the landscape of somewhat esoteric sound.

I was reminded of this a week ago, when I reviewed Winter’s funny, heavy, sad, sweet, and masterful debut at Carnegie Hall for GQ. In that review, I mentioned how the live renditions of those songs reminded me of the astounding Ukrainian pianist Lubomyr Melnyk (if you don’t know Melnyk’s music, it is a gift for the world) and of black metal at large, music that may seem off-limits for piano songs that, at times, can be called something like pop. Thinking back to those interviews, though, I wouldn’t be surprised if Winter has at least some familiarity with something in those lanes. That’s what, in part, makes his songs so compelling—they pull the unfamiliar into the familiar, feeding an old fire new wood.

Please pay special attention to the cache-nez, or “hide-nose.”

The Illustration Department breaks down how illustrators slowly transformed Saint Nicholas, the “tiny, pipe-smoking, soot-covered elf” from Clement Clarke Moore’s poem, into the jolly man in red we now know as Santa Claus.

— in

The name “Santa Claus” comes from Sinterklaas—the Dutch nickname for Sint Nikolaas, or Saint Nicholas. Sinterklaas was inspired by Saint Nicholas of Myra, otherwise known as Nicholas of Bari (where my parents are from). St. Nick was known to secretly dole out a gift or two. He often left coins in people’s empty shoes. His biggest claim to fame involved giving three Christian women dowries so they didn’t have to become prostitutes.

Thomas Nast’s Santa Claus in Camp was the first known, official introduction to modern-day Santa. It appeared in the January 3, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

“In this image,” wrote librarian and archivist Rachael DiEleuterio, “Santa visits a Union encampment, distributing gifts to soldiers. Most notably, Nast dressed Santa in a coat patterned with stars and trousers striped like the American flag. Santa holds a puppet labeled ‘Jeff,’ a not-so-subtle swipe at Confederate president Jefferson Davis. The message was unmistakable: even Santa supported the Union cause. Over the years, Nast continued to refine and elaborate Santa’s image. His illustrations provided the first known references to Santa living at the North Pole and maintaining a toy workshop—details that soon became fixtures of the Santa Claus mythology.”

Ryan Hyman, a curator at the Macculloch Hall Historical Museum in Nast’s hometown of Morristown, New Jersey, pointed out that Nast fashioned Santa—all bearded and rotund—on himself.

Then, in 1917, the Saturday Evening Post publishes J.C. Leyendecker’s rather svelte sidewalk Santa. He’s clothed in red and white. Why red and white? Well, in those days, a palette of red, yellow, white, and black is all an illustrator needed to create a “full-color” piece. It was faster to paint with a limited palette. And easier (and cheaper) to print.

So, if anything, Santa is red and white today because of creative expediency and printing limitations.

Art & Photography: , , ,

Video & Audio: and

Writing: , , ,

The Wall Street Journal has launched , a newsletter from the Opinion desk. It “will address questions and controversies arising from the culture. We won’t ignore Washington and Wall Street, but we’ll cast a wider net.”

The designer joined Substack, where she’s been sharing details about her December garden (we expect it will look great in spring) and a holiday gift guide.

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

2025-12-13 22:02:11

This week, we’re learning to distrust our eyes, selling out at Art Basel, hunting for vintage cookbooks, and appreciating a Nintendo soundtrack.

Everybody wants Warner Bros: Shortly after Netflix’s proposed $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros Discovery sounded alarm bells throughout Hollywood, Paramount launched its own hostile takeover bid, offering $108 billion. Although Netflix, with its dominance of streaming and well-documented skepticism of theatrical releases, has provoked special concern, does it really matter which giant takes over the WB? In an op-ed in , Jane Fonda writes about the dangers posed to both art and jobs when studios consolidate, regardless of who winds up holding the keys. As notes, this is hardly the first time the WB has been bought and sold. And many—including —see these most recent bids as not just bad for Hollywood, but illegal: “It’s just a merger to monopoly, and everybody knows it.”

Disney’s deal with OpenAI: Disney—historically one of the most IP-protective companies in the world—has signed a deal with OpenAI that includes licensing over 200 of its characters to be used in Sora, OpenAI’s video generator, along with an investment of $1 billion. To , this seems like a bad idea on many levels, from Disney’s bottom line to the impact on creative workers already struggling. As points out, this may not be great news for OpenAI, either; Disney has a history of investing in ventures just before they go belly-up.

Legacy media on Substack: and have both joined Substack in the past couple of weeks, with a plan to share stories from their magazines with readers on the platform. The New Yorker’s first essay was especially appropriate for the new space: Jay Kang considers whether the internet has been good or bad for readers, citing Substacker and critic to explore the question. Though the answer may seem obvious, there are no easy answers here; or, as puts it (borrowing a phrase from ), the piece is “nuanced AF.”

In her guide to appreciating craft and artistry, Kendall Waldman ventures into a vintage cookbook shop filled with strange treasures.

— in

“I’m not a scholar of anything,” Joanne Hendricks told me, unconvincingly, moments after describing a treasured piece she regrets selling: an 1884 Percy Bysshe Shelley essay on vegetarianism she once found at the Shelley Society, just to the right of the Spanish Steps in Rome. As evidence of her professed lack of scholastic expertise, she cited her sister-in-law, “who knew absolutely everything,” a real scholar, she insisted, the kind of woman who could name the exact town where Shelley died. “Lerici,” she added, a beat later.

“That thrilled me,” Joanne said, in her soft, whistling teakettle voice. “And I’ve never been able to find another copy.”

Joanne Hendricks, Cookbooks, is a perfect place. You’ll know it by its silvery, splintered door, weathered by a thousand seasons, and a small brass plaque where the mail slot might be, simply engraved: Cookbooks. It’s a portal into someone’s lifelong obsession.

Inside the townhouse where Joanne and her family have lived since the late ’70s, the front parlor has been repurposed into a treasure trove of gastronomic history: cookbooks, cookware, engravings, dishes, oddities, ephemera, all manner of delights relating to food, eating, and the pleasure of the senses. (There are enough gardening and flower books to illustrate this expanded worldview.) A centerfold from Andy Warhol’s illustrated cookbook Wild Raspberries hangs, framed, on the wall. The whole room is as one would hope: giddy, romantic, creaking.

I knew I wanted a book, though they’re not cheap, and soon I was sitting on the floor, greedily surrounded by the volumes I’d pulled: M.F.K. Fisher’s novel with the perfect title I’m almost reluctant to share, Not Now but Now; The New Chinese-Kosher Cookbook; 365 Orange Recipes; Tiffany’s Table Manners for Teen-Agers (when did we stop spelling it like that?); an omelette book that begins “How I Came to Be an Omelette Maker”; The Potato Book; a 1973 Hampton Day School potato recipe anthology with a foreword by Truman Capote.

I left with an unusually sized Japanese Country Cookbook, published by Nitty Gritty Productions in 1969. The paper is textured like corrugated cardboard, ironed for supper. These details are the mark of things made differently, made for the joy of making, and for the delight of someone who’d notice.

Joanne is a living example of the craft of taste—a woman who has spent her life in the flow of curiosity, in pursuit of the undiscovered, in the protection of things worth preserving and skills worth memorializing. Taste is often treated like little more than an inheritance or a personality trait, but in reality it’s a craft, a skill one has to hone through attention, revision, revisitation, and a devotion to getting something as ineffable as one’s own preferences just right, like a perfectly clarified broth.

At Art Basel Miami, “Elon Musk” is on all fours, pooping. The viral installation reaches for subversion, but, Brendon Holder notes, “centering money in the world’s biggest art mall isn’t the ‘gotcha’” the artist thinks it is.

— in

On the ground floor of Art Basel Miami’s convention center, Elon Musk is on all fours, pooping. Next to him is Jeff Bezos, prancing about on his hind legs while Mark Zuckerberg, paws to the floor and ass to the sky in a deranged Child’s Pose, peers into the crowd with his signature slack gaze. Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol are there, too, completing the sausage fest with Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple, the creator of the art installation.

The installation, named “Regular Animals,” features freakishly fleshy replicas of the men’s heads affixed to the bodies of beige robot dogs that jitter and tweak in a square, short fence. Beeps putter out from the litter as the pups step over an array of discarded photos they have ejected out of their robotic anuses. Pictorial excrement. The porous details of their faces earn an impressive verisimilitude, which, in turn, achieves the desired spectacle.

When I saw the installation on Thursday, the last day before the Art Basel convention became open to the public, there was already a mob of spectators and collectors with phones snapping up the mockery of the most powerful men on the planet, mouths smirking at the canine fuckery as if their snarls could somehow adjust the imbalance of power held by the figures. A few spectators—all men—stepped into the dog ring to pick up the sheets the DOGE-coded doggies were shitting out. The bums of each “Regular Animal” produced sheets of paper, a photo of the crowd, because, of course, these dogs were also surveilling and recording us as we were surveilling and recording them. Each photograph was rendered to the artistic viewpoint of the personified puppy: for Picasso, the photos were abstracted with the geometrical edges of Cubism; for Warhol, it was tinged with the vibrant hues of Pop Art; and for Musk, it was bleak, black, and white.

According to Beeple, the alignment of these wealthy men with Warhol and Picasso is meant to represent a shift in cultural custodians, moving from agents of artistry to agents of algorithms and AI. The work posits that technology has become the dominant canvas of culture today, and, as a result, Mark, Jeff, and Elon are meant to be viewed in tandem with some of the art world’s legacy acts. I suppose the work is meant to confront, to be urgent, to subvert, but the installation’s positioning at Art Basel Miami, which is estimated to generate hundreds of millions in art sales and over half a million dollars for Ron DeSantis’s Florida, tips its hat to another theme—that the art world, and popular culture, has not only become completely interlocked with capital and corporate funding, but that money has perhaps become the art world’s most prevalent muse.

By relegating the richest men in the world to tweaked-out beasts, Beeple’s “Regular Animals” reaches with strained fingers at subversion, attempting to make the men victims of their own technology through didactic allegory. But all abstraction is lost when the fixture is placed within the Art Basel convention center, only a five-minute escalator from the Chubb Insurance Collectors Lounge, navigated through the UBS-powered Art Basel mobile app, and the surrounding beach parties funded by Chase Bank. And this isn’t a knock on Art Basel; the goal of the convention is to sell and get artists paid. No one walks into the convention center unaware of its reliance on patrons. Yellow stickers that indicate the sale of a piece are proudly placed next to a work, “just to let ya know” it has been taken off the market in a private sale days before the convention’s public opening, and you’ve, unfortunately, missed out—rats! “Regular Animals”’s unhooding of the power men who fund the circus doesn’t do anything to disempower them; the artists, the gallerists, and the surrounding partygoers are acutely aware of who is picking up the check. Positioning their heads on animals is as effective as a double-underlined sentence: excessive, loud, rudimentary, and in poor taste.

Centering money in the world’s biggest art mall isn’t the “gotcha” Beeple believes it to be. Despite the aesthetic success of the installation’s surrealism and its captivating images of body horror, the piece’s effect is that of realism. It just feels like we are saying the loud part, well, out loud.

Wii Tennis’s theme song may be nostalgic, but it’s also more complex than it might seem—and the work of one of Nintendo’s most influential composers.

— in

Stripped of the emotional context, Kazumi Totaka’s theme for Wii Sports could be mistaken for just background music. It is bright, bouncy, and vaguely jazzy, designed to welcome your parents or grandparents to motion-controlled tennis. Which is exactly the point.

Totaka is Nintendo’s most quietly influential composer. He’s been with the company since 1990, provides the voice for Yoshi, and has hidden a 19-note personal melody called “Totaka’s Song” in at least 25 different games—sometimes requiring you to wait several minutes on an obscure menu screen to hear it. In Animal Crossing, the character K.K. Slider is named “Totakeke” in Japanese, a direct reference to him. He’s both a signature and a ghost in the machine.

But the Wii Sports theme is actually pretty damn deep. Hooktheory’s analysis calls it “more complex than the typical song,” with above-average scores in chord complexity, melodic complexity, and chord-bass melody—sections modulating through B major, C major, A major, and D-flat major. It draws on bossa nova, lounge, and what one music critic called “that Classic Nintendo Fusion Jazz Sound” to create something that occupies a peculiar audio niche no one else has quite filled.

Also interesting: the scale of its reach is staggering, approaching Nokia theme song levels (but not quite). The Wii sold over 100 million consoles. Wii Sports sold nearly 83 million copies, making it the best-selling single-platform game ever. It was bundled with every console outside Japan, but that alone doesn’t explain its cultural penetration. Retirement communities formed Wii Bowling leagues, physical therapists prescribed it for stroke recovery, and, importantly, it redefined gaming demographics so completely that Nintendo’s marketing showed grandparents before it showed teenagers.

There’s a case to be made that Totaka’s theme may be among the most-heard compositions of its generation. Eighty-three million copies in living rooms from Tokyo to Toledo, playing on startup for families, seniors, and people who had never touched a video game controller.

It needed to feel welcoming without being cloying, sophisticated without being intimidating, memorable without demanding attention. That’s harder than it sounds.

As AI image generation improves, people have begun mourning the end of photographic evidence. But as Julien Posture points out, photographic skepticism has a history as long as the art of photography itself.

— in

Last week marked the end of photographic evidence, or so I heard.

The two pictures that tolled the bell of evidentiality depicted a woman in a restaurant, her eyes closed as her hand supported her head as she smiled softly. In front of her was a cocktail, a mug, a glass of water and a small vase with a few sprigs in it. In the background, a bartender was making another cocktail at the counter. While the two images depicted the exact same scene, the pictures were strikingly different, yet in ways difficult to describe. For lack of better words, one ‘looked’ fake and the other real.

The difference between the two was not explained in terms of their qualities but their provenance: ‘Nano Banana vs Nano Banana Pro’ the caption read. This is typical of AI fans’ chronology, where time is measured and marked by the release of new models, each new one supposedly heralding a new era. Over the past few years, we have been through so many of these technologically induced epochal shifts, it is hard to summon the attention and energy to feel amazed by them. And yet, something about the ‘Nano Banana Pro revolution’ (sigh) gave me pause.

On Instagram, many people reposted the images with similar captions like ‘2 months of progress has made AI indistinguishable from real life’ or ‘images are no longer witnesses and now they are mere hypothesis’. ‘You cannot trust your eyes anymore,’ said another one. In a popular repost on Twitter, a user wrote: ‘And just like that, the age of photographic evidence is over. 1826-2025. Update your epistemology accordingly.’ Oh boy.

Was our “epistemology,” i.e. the way we know things, really over? Was it the end of photographic evidentiality? Did November 2025 mark a paradigm shift as we entered yet a new epistemic era? Maybe I’m blasé, but I had hoped such upheaval would feel like something. But maybe, just maybe, nothing has changed.

The year 1826, often evoked by those comments as the beginning of photographic evidence, refers to the date of the first known photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras by French icon Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Back then, Niépce had to leave his camera obscura to soak in photons for a whole day to get this image. In 1839 came the first public announcements of the official invention of photography in France and the UK, but it wasn’t until 1860 that photographs would be used in court. The medium was quickly associated with objectivity, as it was a direct imprint of the sun. But even then, the courts had to contend with and make room for the kind of evidentiality photographs afforded.

In one of my favourite metaphors about what kind of evidence a photograph is, archivist Rodney Carter explains how in an 1865 court case, ‘Contradictory testimony regarding the photographs submitted into evidence was given, leading the plaintiff’s counsel to argue that […] the photographs were nothing but “hearsay of the sun.”’ As soon as photographs were invented, they were also manipulated, retouched and doctored, a threat which cast a shadow (pun laboriously intended) on their evidentiality.

Art & Photography: , , ,

Video & Audio:

Writing: , , ,

, “the premier literary-intellectual magazine in the English language,” has joined Substack, where the editors will offer articles, interviews, and “a range of other ephemera, essays, investigations, and criticism.”

The team behind the Points Guy has launched , where they’ll be sharing tips and tricks for travel deals.

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

2025-12-06 22:01:46

This week, we’re rewriting Dostoevsky, remembering Tom Stoppard, building community, and time-traveling back to the days of bulky iMacs and AIM.

And the Pantone color of the year is. . . white. Pantone released its annual color choice for 2026: Cloud Dancer, a “billowy white.” For some, the color is a “comfort neutral” or a “blank canvas,” exactly what we need as we face a new, likely turbulent year. For others, the lack-of-color color is everything from boring to a recession indicator to a subtle reminder of the Sydney Sweeney “good genes” controversy. Hard to say whether Cloud Dancer is being received any better than 2025’s Mocha Mousse (though, to be fair, people have worn a lot of brown this year).

The $140,000 poverty line: Substackers are debating what it costs to raise a family in the United States. In his Substack and for The Free Press, financial executive Michael W. Green took aim at the federal poverty calculation. Adjusting for modern expenses, he argues, the poverty line for a family of four should be raised from about $32,000 a year to about $140,000. Some have pushed back, including economist Noah Smith, who wrote a post in Noahpinion arguing that the idea was “very silly.” In The Purse, Lindsey Stanberry and Alicia Adamczyk took a practical approach, examining a few real families making that much and describing their lifestyle.

Spotify Wrapped is here. The “listening age” was an especially savvy addition this year, judging by the number of 20- and 30-somethings sharing their geriatric stats. Meanwhile, Substacker created his own version specifically for Substack publishers. Go forth and wrap!

Patrick Kho reports on a new vision for third spaces—those gathering spaces beyond the workplace and the home. This new version is less a physical space where communities might (or might not) interact, and more intentional collectives that are “people first, space second.”

— in

Athena is among several young people creating what I call “traveling third spaces”: new communities that are people-first, space-second. Traveling third spaces are not physically fixed; they move across cafes, malls, restaurants, and host various programming for a singular community in a particular city. And they exist around the world—in London, a community of the name One House Social Club brings people together in “London’s Best Spots”; in New York, a traveling dinner series called (get this) 3rd Space gathers creatives and entrepreneurs for three-course meals around the city.

The traveling third space recognizes that public spaces are not a guarantor of belonging; they are merely a base upon which people form connections and bond over shared interests.

Ivana Duong, a graphic designer, is engaging in similar work. She’s the creative producer of Critical Mass, a collective/community with regular, twice-monthly meetups for creatives in Hong Kong.

“Once you graduate college and settle more into having a more adult lifestyle, it’s harder to find community,” Ivana says. “With Critical Mass, we niched down particularly to artists and creatives because that’s what the team’s familiar with.”

Critical Mass’ recurring meetup (named “House Party”) is held at Heath Mall every other Wednesday. The draw, Ivana says, is just for a “low-stakes hangout.” Spontaneity is a key part of their programming: people can intersperse in and out at any given time and hang out. It’s also completely free. The collective regularly hosts workshops around zine-making, tattoo design, and logos-making on Figma—activities which continue to attract people with a creative sensibility. (Full disclosure: I’m actively involved in Critical Mass’ programming, and can attest to this firsthand.)

Having a group of creative people in one place “sets a theme” and so “allows for a certain audience to gather” in a way that just going to the park or a cafe might not. At a Critical Mass House Party, you already have common ground with people, as opposed to just, say, approaching someone at a bar. “It establishes beyond the basic need of a place to relax [after work],” says Ivana. “Like, oh, creatives are here!”

Tina Brown dives into the unconventional life and brilliance of the playwright Tom Stoppard, who died last week at the age of 88.

— in

No, not Tom Stoppard, too! In the verbal slop of modern culture, the loss of his flashing, ambidextrous wit and his playful erudition is a literary blow especially hard to bear. His writing was the enemy of the turgid absolutes that blight our contemporary discourse. He once said: “I write plays because dialogue is the most respectable way of contradicting myself.”

I have been obsessed with the great Tom since our first meeting, when I was sixteen. He was then the rising—or, rather, the already blazing—thirty-one-year-old star of British theatre. The blaze had been ignited by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which burst from a humble venue at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and wound up at the National Theatre in 1967. When asked later, in New York, what the play was about, he replied, “It’s about to make me very rich.” And it did.

In 1969, Tom showed up at my childhood home in Buckinghamshire to see my film producer father, George Brown, about the possibility of bringing his most recent play, The Real Inspector Hound, to the screen. He lived only twenty minutes away, and eventually bought a country manor nearby for a new life with his second wife, Miriam, a glamorous TV doctor. They became, in a way, the first media power couple, until Tom blew up his marriage in 1990 for one of his leading ladies, Felicity Kendal. (Cf. Charlotte, the wife in The Real Thing, his play about marital infidelity: “There are no commitments, only bargains.”)

He turned up that day at our home, I recall, wearing black and yellow patent shoes, flared velvet trousers, and a trailing student scarf. He chain-smoked as if sipping through a straw. The whole camp look was set off by that sardonic but measured voice and the exotic way he emphasized his ‘r’s. When Tom uttered words like “meretricious” or “rancorous,” the liquid consonants rolled off his tongue with languorous precision. He probably had one of the three most voluptuous mouths of the mid-20th century; the other two were possessed by his friend Mick Jagger and the late Martin Amis. I was mesmerized (though, as an awed teenager, ignored) by a playwright who was also, to all appearances, a rock star.

Tom later became a treasured friend and, five decades later, I still find The Real Inspector Hound the most screamingly funny work in the entire Stoppard oeuvre. Hound is so simple, yet so ingenious in its cavorting concept of a play within a play, centered on two pretentious theatre critics, the lofty Birdboot and the embittered second string, Moon, who get pulled into the country house murder-mystery they have come to review. The play opens with a dead body onstage that remains there for the entire performance, ignored by all the characters, who seem not to notice that it’s a leading clue. The housekeeper, Mrs. Drudge, answers the phone in such Mousetrappish stage-direction lingo as, “Hallo, the drawing room of Lady Muldoon’s country residence one morning in early Spring?”

Here was classic, joyful absurdity, devoid of the political confrontation then in vogue in the work of playwrights such as Howard Brenton and David Edgar. “I get deeply embarrassed by the statements and postures of ‘committed theatre,’” Stoppard told an interviewer in 1973. “I’ve never felt that art is important. That’s been my secret guilt.” It’s extraordinary to think that none of Tom’s plays would be staged at the Royal Court Theatre until Rock ’n’ Roll, in 2006. There was a feeling among advocates of committed theatre that Tom was little more than a “university wit”—pretty rich considering that, by choice, he never went to college. Who needed Oxford or Cambridge when you could satisfy your passion for finding things out by shoe-leather reporting? For a time, he held down the job of motoring correspondent for the Western Daily Press, even though he couldn’t drive. (“I used to review the upholstery,” he explained.) Unburdened by a degree, Stoppard spent the rest of his life in a kind of autodidactic frenzy, risking one deep dive after another into subjects as varied as linguistic philosophy, landscape gardening, and nineteenth-century Russian revolutionaries. But not once did he drown in solemnity.

Vāneçka has begun transposing Dostoyevsky’s classic Notes from Underground into a modern context, translating the text faithfully while updating it to a contemporary setting. In so doing, he brings out the original’s comedy, eschewing the “archaic translations” that “completely bury its manic, self-contradictory energy.”

— in

I’m a sick man. . . I’m a spiteful man. Unattractive man I am. I think I have depression. Although I don’t understand anything about my condition and don’t know whether I have it at all. I’m not in therapy and never been to therapy, though I respect psychology and have read Freud. Besides, I constantly self-diagnose; well, at least enough to respect the profession (I’m smart enough not to self-diagnose, but also educated enough to self-diagnose). Nah, I won’t go to therapy out of spite. You won’t understand it. But I do understand. I obviously can’t explain to you for whom exactly things are worse because of my spite; I know perfectly well that I’m not hurting therapists by not going to therapy; I know better than anyone that I’m only fucking myself over with all this and nobody else. But still, if I don’t go to therapy, it’s out of spite. I’m depressed, so let me get even more depressed!

I’ve been living like that for a while—maybe twenty years. Now I’m forty. I used to work, now I don’t. I was a toxic IT support guy. I was rude and took pleasure in it. I mean, I didn’t steal company equipment, so I had to compensate myself somehow. (Bad joke; but I won’t delete it. I wrote it thinking it was witty, but now that I see I just wanted to show off pathetically—I’m deliberately leaving it in!) When users would come to my desk with their tickets, I’d grind my teeth at them and feel inexorable pleasure when I managed to upset someone. Almost always managed to. Mostly they were all timid types: you know—users. But among the self-important ones there was some middle manager I especially couldn’t stand. He refused to submit and kept stubbornly following up on tickets. I had a war with him over his tickets for a year and a half. I finally broke him. He stopped following up. Though this happened when I was younger. But do you know, dear readers, what the main point of my spite was? The whole thing, the nastiest thing, was that every minute, even in moments of my strongest bile, I shamefully realised that I was not only not spiteful, but not even a bitter person, that I was just barking at shadows for nothing and amusing myself with it. I’m foaming at my mouth, but bring me some little treat—a cup of coffee or whatnot—and I’ll calm down. I’ll even feel touched, though afterwards I’ll grind my teeth at myself and suffer from insomnia for months. That’s just my way.

I lied to you above, lied that I was a toxic IT guy. Lied out of spite. I was just messing around with the users and that one guy, but in reality I could never be mean to anyone. I was constantly aware of many, many other feelings opposite to that. I felt them swarming in me, these opposite feelings. I knew they’d been swarming in me my whole life and trying to get out, but I wouldn’t let them, I didn’t, never did. They tortured me to the point of shame, brought me to convulsions and—I was completely fed up with them! Don’t you reckon, dear readers, that I’m repenting something before you now, that I’m asking your forgiveness for something? . . . I’m sure that you do reckon. . . But anyway, I assure you, I don’t care even if you do. . .

Drew Austin on the adolescence of the internet, and the difficulty of capturing the moment in media.

— in

Last week, I went to a party at my friend’s parents’ house, and her lime green iMac from high school had been taken out of storage and placed on a side table in one of the rooms. Long since functional, it sat on display like a sculpture and got a lot of attention. Not just an iconic piece of Y2K-era industrial design and a perfect visual emblem of an idealized pre-9/11 culture, the iMac G3 is also a powerful source of personal nostalgia for older millennials, evoking a phase of youth as reliably as the AOL Instant Messenger pings and chimes that would issue from its speakers nonstop. Before computers flattened into two-dimensional screens and effectively disappeared, when they still possessed some awkward heft, this was about as good as they ever looked.

That was my second encounter with a candy-colored early-’00s iMac in the last two weeks. An identical one appeared in a play called “Initiative” I’d just seen, currently showing at the Public Theater for another week, which takes place over four years of high school between 2000 and 2004. The play is a coming-of-age story about a group of friends who live in suburban California and bond over an ongoing Dungeons & Dragons game that runs the course of their high school years. The play was excellent (and five hours long), but what initially interested me about it was the choice to set it in the early ’00s, not just because I’ve been paying attention to how aging millennials like myself are reflecting upon our own past and narrativizing it but because those years remain a surprisingly under-historicized era—now as far in the past as the ’70s were in 2001, yet somehow not feeling all that distant or entirely separate from the present, the way prior decades did (in contrast, the ’80s already felt quite dated in the ’90s). The lime green iMac and similar props, along with constant AOL Instant Messenger usage and occasional references to background events like 9/11, thus perform an important function in the play: Without those details, the setting might pass for contemporary. The mall attire that the suburban teenage characters wear, for example, represents the early ’00s but has also returned in various forms in the years since, and still does. You don’t have to look too hard to find “Y2K fashion” or cargo pants today.

“Initiative” is not specifically about the internet, but it captures the technology’s rapidly growing role in early-’00s social life. The specific time period it portrays, between the summers of 2000 and 2004, bookended by misplaced Y2K anxiety and the arrival of Facebook, was solidly the AOL Instant Messenger era: AIM was released in 1997, peaked in 2001, and declined more rapidly after 2005, losing ground to SMS texting and social media. Early in the play, one character’s younger brother helps him download it, telling him that “AIM isn’t nerdy, it’s just a way to talk to people online.” The play is peppered with such amusing reminders of what it felt like to be figuring out the internet, before it was all so obvious (“message boards aren’t real life!”), and the janky early-’00s internet forms a backdrop for the characters’ similarly awkward adolescence: simultaneous spoken AIM conversations overlapping with in-person dialogue, case-sensitive usernames with underscores projected onto the walls of the set, Goatse links spelled out verbally by a character.

I rarely think about AIM today, despite the huge role it played in my life as a teenager. And when I saw the lime green iMacs, I realized I never think about those anymore either. Napster endures in memory as an inflection point for media consumption and the music industry. But overall, that era will increasingly seem like a transitional phase, more difficult to place as time passes and history is divided into two parts, before and after the internet. September 11 was the ultimate historical event, meanwhile, occurring right in the middle of all this, during AIM’s peak year of usage. Perhaps 9/11 has drawn all the air out of the room, dominating our memory of that time so completely that it’s hard to see anything that didn’t align with the seriousness it dictated. Any work of fiction set around that time must carefully measure its proximity to that event or risk being somehow “about” 9/11—a problem that ’80s and ’90s period pieces rarely face.

The migration of culture into digital space has surely made the recent past feel more ahistorical. In that sense, the early ’00s were the end of something as well as the beginning of something else. It’s not that any less happened then but that more of what did happen resists straightforward depiction. The challenge of portraying online activity in film and TV has always fascinated me, because it raises uncomfortable questions about how we use that technology as well as how storytelling works. Showing a screen on another screen usually feels like the worst solution to the problem. Another option is to set the story in a time or place where screens don’t exist. There is an archaic but persistent idea that any drama worth portraying happens in real life, not on a screen, but that is probably just a holdover from when screens were one-way channels of static, pre-packaged entertainment, not portals to a dynamic environment where a lot does happen. People like to point out that screens never appear in our dreams, suggesting that deep down we all long to get off our phones, but as I’ve wondered before, maybe it’s just that the dream is the screen, our phones framing our reality so comprehensively that we already think we live inside of them.Keep reading

Art & Photography: , ,

Video & Audio:

Writing: , , ,

, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, has joined Substack. As he says, “Communication is changing, and I want to be a part of that. People have a right to know how decisions that affect them are taken and why. That’s why I’m now on Substack.”

also joined Substack this week. The former Vice President’s welcome video echoes Keir Starmer’s message: “I think it’s so important to be where people are, and speak with people where they are, and that includes online and here on Substack.”

has joined Substack, launching as “a book club, but for magazine articles.” Each week the editors will share a New Yorker story for free, for readers to enjoy and discuss.

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

2025-11-29 22:02:23

This week, we’re analyzing home-screen metaphors, considering suffering and God vis-à-vis Peanuts, and learning to write grammatically correct greeting cards.

The bubble popper: , the investor and hedge fund manager best known for recognizing and profiting off the subprime mortgage crisis (as detailed in The Big Short), joined Substack with a bang. In his first post, he argues that the AI market displays all the classic hallmarks of a bubble. It prompted a swift reaction: Nvidia sent a memo to Wall Street refuting his points, but Burry’s second post pokes yet further holes in their assertions.

Lizzo on flute, and weight loss: We welcomed another pop star into the Substack constellation. This week, joined with an impassioned essay about publicly losing weight in the midst of the Ozempic boom. She followed it up with a video of herself performing a flute solo to the tune of “Berghain.” Your move, Rosalía.

The Nuzzi-Lizza saga continues: For those following the political and media scandal surrounding Olivia Nuzzi and , the bombshells haven’t stopped dropping. This week Lizza released Part 2: She Did It Again and Part 3: Catch and Kill. Come for the firsthand account from Lizza, stay for ’s characteristically incisive review of the whole ordeal. As Kate Lindsay puts it, “Watching a breakup get rehashed back and forth through New York Times profiles and book excerpts and lore drops on Substack has me thinking we might be in a promising era of media after all.”

Adam Aleksic on the ways the digital realm mimics the domestic, while offering only an illusion of privacy and control.

— in

The wooden stairs in my childhood home had a creaky step. I can still vividly picture the way it groaned under pressure. It was such a loud, incriminating sound that I would usually hop over it on my midnight runs to the kitchen. Otherwise, I would wake the entire house.

It takes an incredibly intimate familiarity to develop that kind of habit. Once you really start knowing a place, you develop your own navigational idiosyncrasies like that. My roommate says he would always grab the railing in a particular way when walking upstairs in his childhood home.

I also see myself developing unique behaviors in the digital space. Only I have the motor memory to immediately open the notes app on my phone. A stranger would have to look for it, but my fingers subconsciously understand where to go. Much like with my childhood home, I have an embodied knowledge of my home screen.

That phrase—“home screen”—has been on my mind recently. The language of the smartphone invites you to think of it as a house. You can “choose your wallpaper,” just like with a real house; you can “lock” your phone like a front door. The metaphor is that this is a private refuge from the outside world. It is a tiny dwelling in your pocket, which you can customize like an actual dwelling to affirm your identity. In doing so, you “tame” the technology, making it feel natural in your everyday life.

The phone, like your house, is a focal point. Everything revolves around it. When you need comfort in the physical world, you go back to the home; in the digital world, you go back to your home screen. There is something calming about a deeply personal environment. It provides a grounding presence which we can retreat to.

A computer, meanwhile, remains more functional. Phrases like “desktop” and “taskbar” create a metaphor that this is a workstation; you have “trash” and “files.” Of course, there are still work-like aspects to the phone and home-like aspects to the computer, but the phone takes on a far more domestic role in our lives. It is not a utility: it is an extension of self.

In his book The Poetics of Space, the philosopher Gaston Bachelard argues that our intimate spaces are deeply intertwined with our imagination and sense of being. When you curl up in a comfortable nook in your home, for example, your consciousness is gathered inward. You have control over this small space, in contrast to the wild, turbulent outdoors. You can focus attention differently in miniature.

As I move between apps on my phone, I notice a vague emotion that I am entering different rooms, each with its own character. The settings app is the basement; the dating apps are the bedroom. No matter where I go, though, there is that coziness of being in a nook. This is my corner of the world; I am free to do what I want. I can let my mind relax, for I am safe and secure from the vast, terrifying world.

Of course, phones only give us the illusion of privacy and control. If apps are rooms, then every room in your house has someone peeking through the blinds. And you might be able to customize your experience to some degree, but automatic updates are a reminder that you don’t really have agency over your cute little space.

Steven D. Greydanus explores the biblical influences on Charles Schulz’s 50-year meditation on suffering, baseball, and childhood.

— in

Schulz wrote and drew Peanuts for nearly a half century—and, while it’s widely agreed that his creative peak was from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, the singular sensibility, ruthless brilliance, and empathy that characterized his work was present from the beginning to the end. Schulz’s 50-year run has been called “arguably the longest story ever told by one human being”; it is too rich and varied a body of work to be encapsulated in a single strip. When I think of Peanuts, among many other things, I think of . . .

Snoopy’s fantasy life;

Charlie Brown haplessly seeking psychiatric help from Lucy, and even more haplessly trying to kick Lucy’s football;

Peppermint Patty consistently pulling D-minuses, and Charlie Brown regularly getting his socks and various other articles of clothing knocked off him by line drives in one losing baseball game after another; and

various unrequited loves (Sally adores Linus, who crushes on Miss Othmar; Lucy is fascinated with Schroeder; and both Peppermint Patty and Marcie are sweet on Charlie Brown, who, of course, is infatuated with the Little Red-Haired Girl).

I also think of allusions to and quotations from various literary sources: Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, Tolstoy, Mark Twain, Scott Fitzgerald, and many others. Above all, the Bible, most often quoted by Linus, though it’s also referenced by Lucy, Charlie Brown, Sally, and even Snoopy.

The Bible has a lot to say about evil and suffering, of course, and suffering is a major theme in Peanuts. All of the bulleted themes above include disappointment, hardship, and suffering. Even in Snoopy’s fantasy life, the World War I Flying Ace often had the worse of his encounters with the Red Baron, and the World Famous Writer’s literary efforts were generally rebuffed by publishers.

Unsurprisingly, Schulz repeatedly referenced the book of Job, which is all about the problem of evil. (He also turned more than once to Ecclesiastes.) The Sunday strip below, from September 1967, embraces Schulz’s preoccupations with baseball, suffering and loss, theology, and the Bible, particularly the book of Job; I know of no one Peanuts strip that sums up more of Schulz’s sensibility than this.

Marion Teniade on the role that turned rom-com rules on their head: Julia Roberts as Jules in My Best Friend’s Wedding.

— in

The titans of the ’90s rom-com—the household names who held the title of “America’s Sweetheart” at various points during the era—each had their signature thing. A Meg Ryan character, for example, was gonna be perky, and kind of fussy, and seem like she read a lot of books. A Sandra Bullock character was often lonely, surprisingly goofy, and the most likely to join a game of flag football. A Drew Barrymore character would inevitably be painfully earnest and also possibly a little bit high.