2025-12-27 02:05:02

After I shared my novel theory of why warm countries are poorer, your avalanche of amazing comments prompted me to respond with two articles. But I kept thinking about some of them, especially this theme, summarized in Astral Codex Ten:

I find this very interesting, and far more thoughtful than most attempts at this question, but I’m pretty concerned about his answer here to the objection that India, Cambodia, etc birthed great empires while being hot and non-mountainous. He says that they may have had high GDP, but always had low GDP per capita, which he pinpoints as the real measure of wealth. My impression is that pre-Industrial Revolution, all countries had low GDP per capita, because they were in a Malthusian regime where economic improvement translated to population density rather than increasing per capita GDP. Any differences between regions reflected minor fluctuations in the exact parameters of their Malthusianism and were not of any broader significance. So I think the India etc objection still stands and is pretty strong.

In other words: In the past, wealth always became people, because humans would simply convert their money into food to feed more children, up until they couldn’t afford to feed any more people.

I respect the author, , tremendously, so that gave me pause, and I’ve been pondering this ever since.

Eventually, I concluded that we could explore this question together on a trip around the world: Fly over a multitude of countries, zoom in on their most characteristic features of development, and from what we see, draw some rules of development and explore how heat and mountains might have affected them.

I’ve been wanting to do this forever anyway, and Christmas week is the perfect time, so please take your seat, fasten your seatbelt, pull up the window shade, and get ready for an adventure!

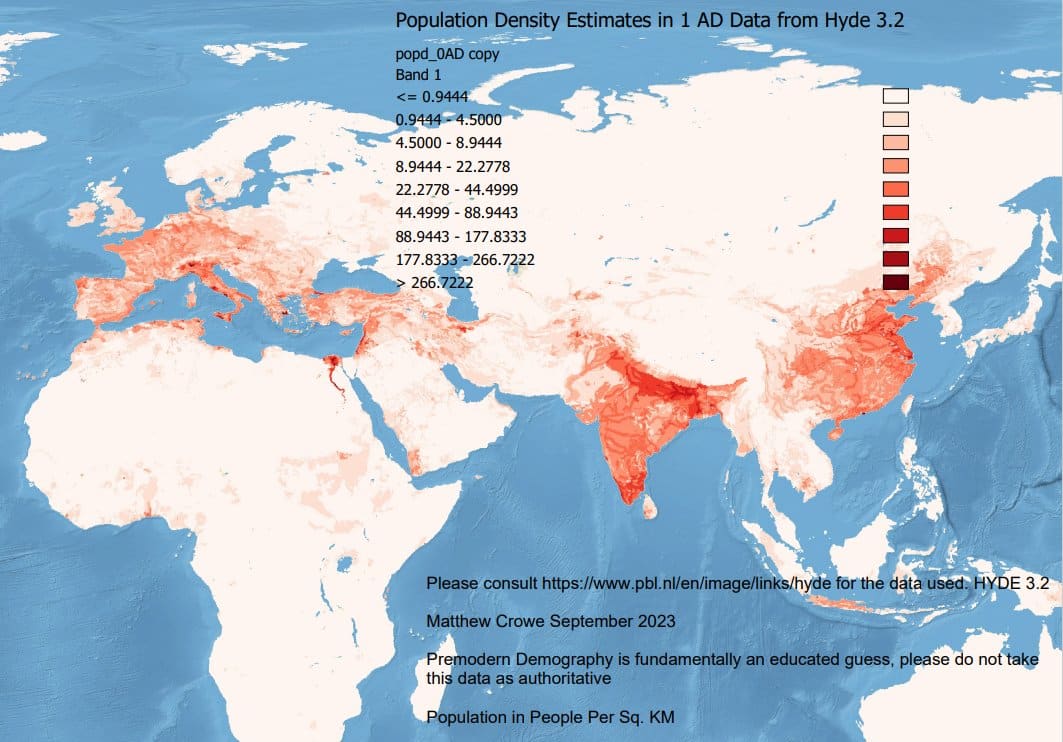

I have a very hard time finding maps of world population density before 1800. Here’s one from 1 AD:

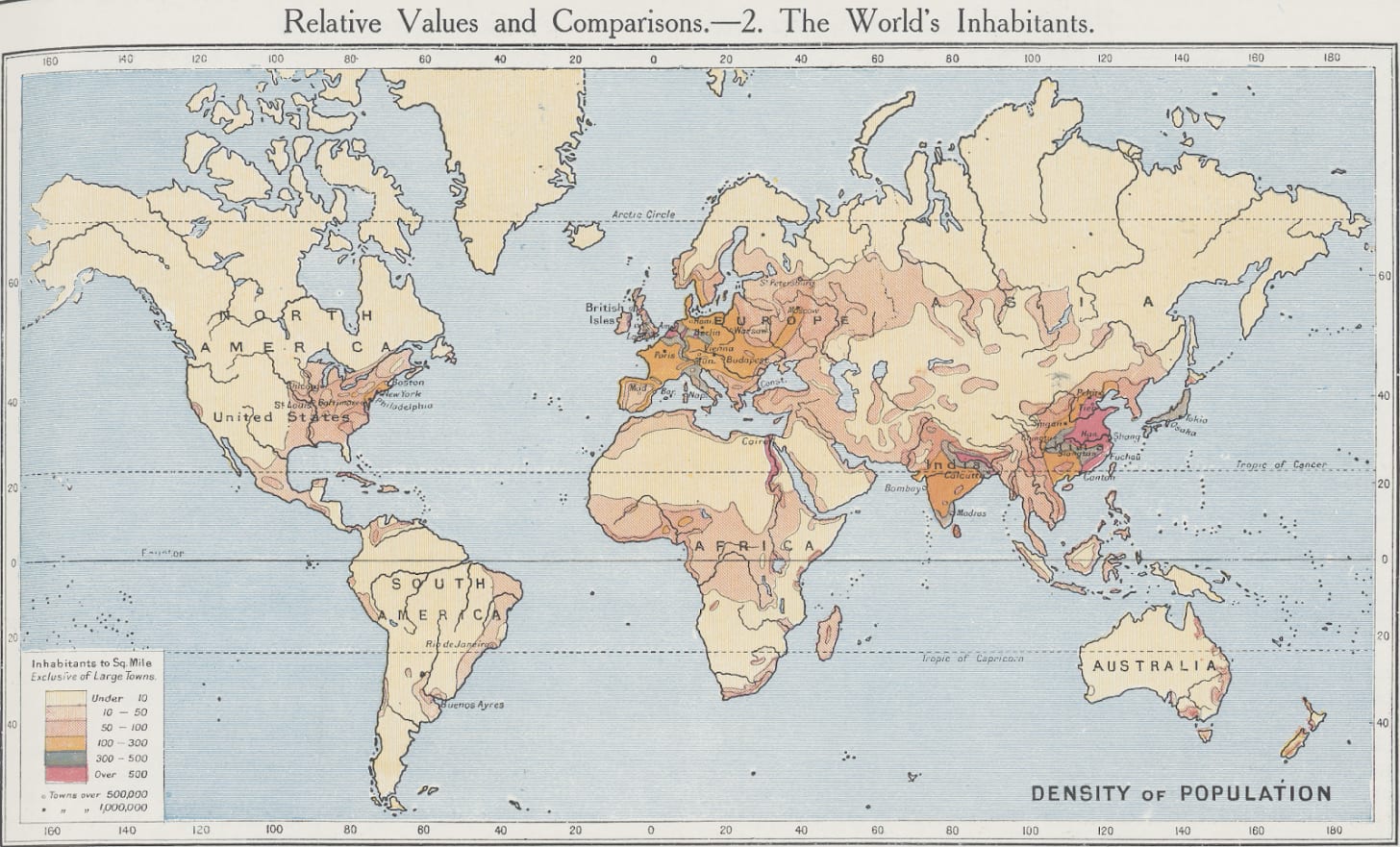

Which reminds me a lot to this map:

And this population density map for 1908:

Put together, we can conclude that the places that had any substantial native population before the Industrial Revolution were:

Europe, and more recently its temperate offshoots (Eastern US, Australia / New Zealand, Buenos Aires, South Africa)

The Middle East (Turkey, Mesopotamia, and the Levant)

India

China

Japan

Egypt

What patterns can we notice?

Most of these are outside the tropics.

There is, indeed, a dearth of population around the equator.

The biggest outlier is India, especially southern India, which is densely populated yet close to the equator.

There are some other pockets of population: the island of Java in Indonesia, Nigeria, western Yemen, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Nigeria, Mesoamerica, or Northern Colombia and Venezuela.

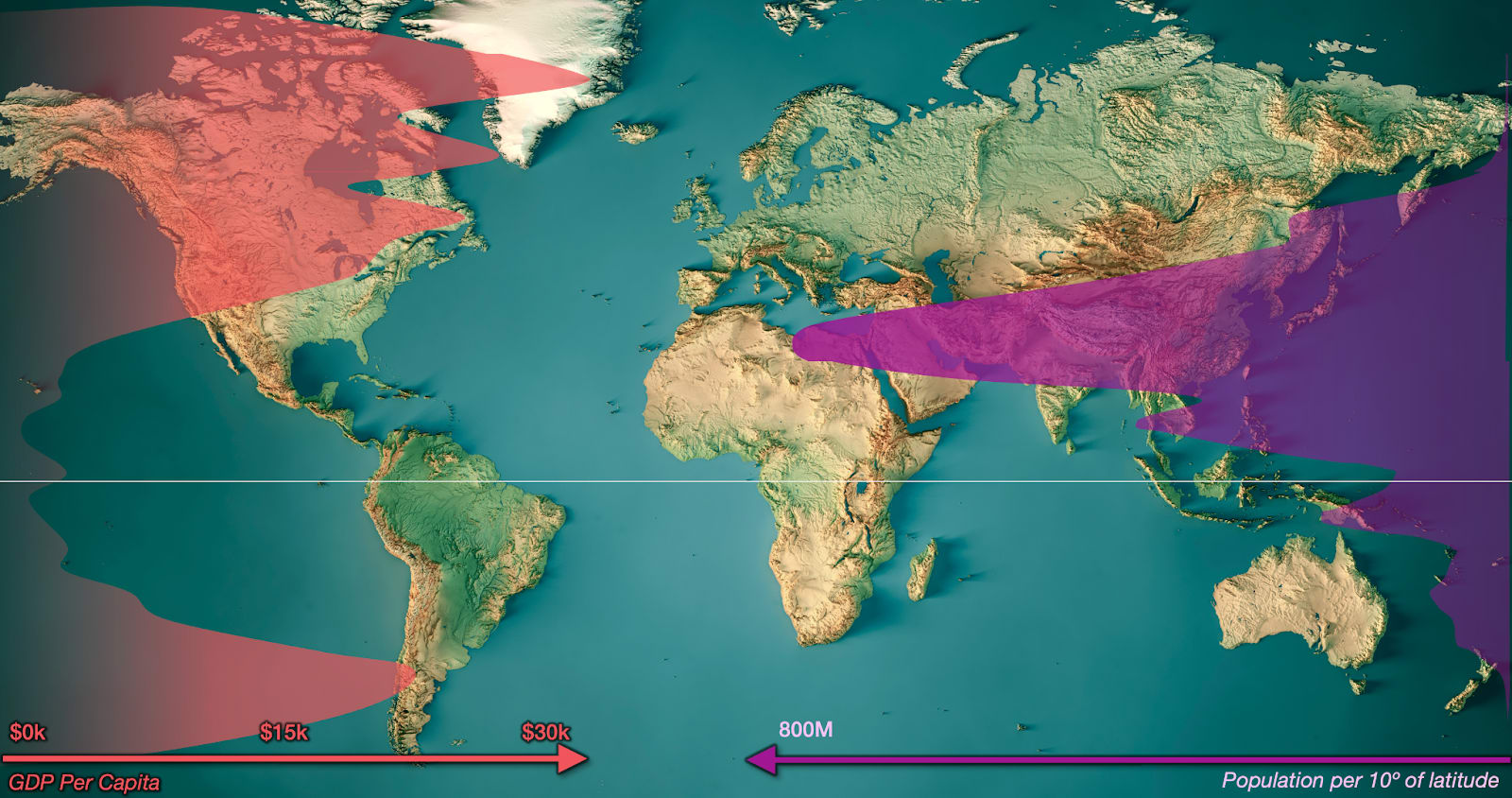

Let’s compare this to a map of population and GDP per capita per latitude today:

We can basically see four main regions:

The very cold and rich region in the Northern Hemisphere, in blue

The rich temperate regions in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, in green

The poor equatorial region, which is also not very densely populated

The transition region, which is poor but very densely populated

Regions 1 through 3 fit the theory that cool countries are richer pretty well. The key question is around region 4: If it is poor today on a GDP per capita basis, why are there so many people? Why has it hosted big empires throughout history?

I don’t think we need to rehash why region (2) is good, so our trip will take us quickly to the polar region (1) first. Then, we’ll switch out the heater for the AC to travel to the equatorial region (3). Finally, we’re going to the more contentious tropics (4).

If you look at a map of population density, you’ll realize this wealth just describes Europe’s Nordic countries.1 It’s nearly all Finns, plus some Swedes, Norwegians, and a handful of Icelanders and Russians.

Their development patterns are quite similar to those of slightly more temperate regions, because they have a similar climate:

They’re just farther north in Europe because the Gulf Stream (and the AMOC) warms them up.

OK so (1) is basically like (2), the temperate regions, extended upwards by the unique shape of Europe and the rotation of the Earth. This also explains the southeastern diagonal of temperatures and populations we saw before: Europe is warm despite being farther north because of the Gulf Stream.

Now let’s travel to the equatorial region, and here is where it starts getting interesting.

You can see it’s quite poor and not very populated.

You might assume that it’s less populated simply because it has less landmass, not because its population density is lower, but this map displaying population density per latitude shows basically the same thing:

If we look again at a population density map today:

The only part here that also seemed to have a big population centuries ago is India. We will look at it later on. Right now, we should wonder the opposite: Why are there so many very empty areas here? Here is a map of global annual precipitation:

Note how rainfall is brutal in Latin America (LatAm) between southern Mexico and Brazil, in Africa (from Guinea Bissau in the west to the Congo in the center), and Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia and Malaysia). Now let’s compare that to a map of erosion caused by rainfall:

Basically the same places that have lots of rainfall also have terrible erosion from rains. And this is a map of land quality:

Virtually all the regions hit by lots of continuous rains have crappy land. Let’s take a few examples, starting with America, because the continent is the only one elongated across all latitudes, so it clearly gives a sense of what happens at each one.

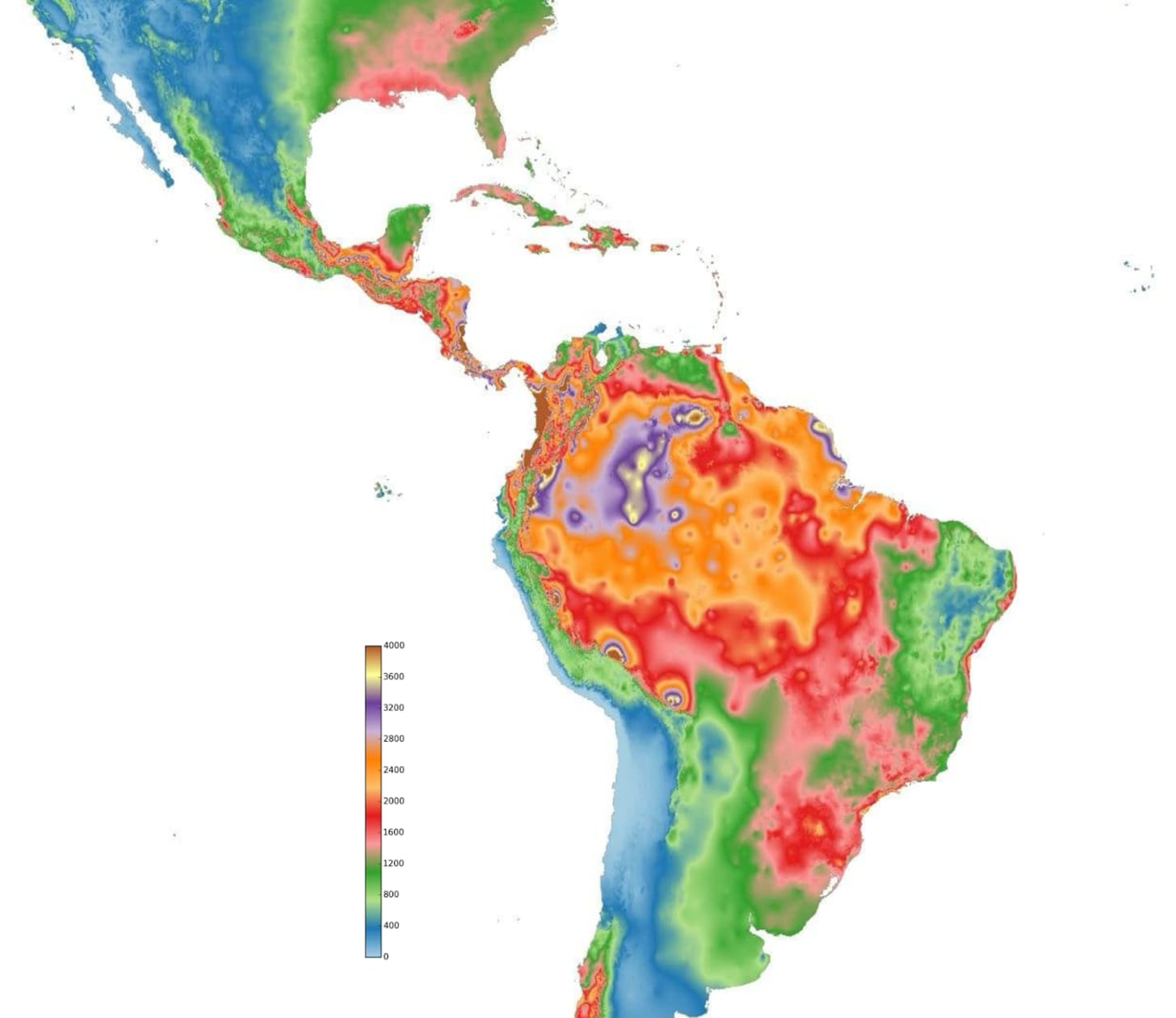

Let’s zoom in on that precipitation map.

When we looked at Brazil, I shared the country’s topography and population density:

Most people live on the mountainous coasts. São Paulo is 760 m high, for example. The south (cooler) is more populous than the north. And most of the cropland is actually to the south, as far from the equator as possible (and in the mountains!):

And more importantly and tellingly, the Amazon is completely empty. Yet it’s a massive flatland irrigated by a river system that competes with the Mississippi’s in terms of volume and number of big tributaries. Equivalent rivers in temperate regions (the Nile, the Ganges, the Yellow River, the Yangtze, the Mississippi, the Paraná…) are all densely populated.

If the Amazon had been in a temperate region, it would be massively populated and rich like them. But it’s empty, and not because of environmental protection efforts. It’s because its land is absolutely terrible for agriculture. When you hear that people are destroying the Amazon Rainforest, that’s not really true. The heartland is protected by geography. It’s the edges that are being destroyed. The Amazon is barren for agriculture because of the constant rainfall erosion.

It’s not the only issue. Diseases, of course. But we can’t just take a map of current disease, because there are so many confounders. For example, more populous areas will have more sick people by definition, even if the population is healthier. They will tend to have more infectious diseases simply because there is more density. More advanced societies tend to have their particular diseases. What we want to get at, though, is what diseases prevented development in the first place. For that, I think we should take as proxies the diseases that are known to have caused the most trouble to humans throughout their development, and at the top of the list is malaria.

It’s especially active in the Amazon rainforest. Flat, low-lying, and rainy.

To escape this terrible fate, Colombians live in the mountains, as we have seen.

Here’s Medellín:

In contrast, the Pacific coast is completely uninhabited, because it’s the hottest, rainiest part of the country, full of impenetrable jungle and hard to turn into cropland. Then, if you look around on the Internet, you’ll hear some of the themes we’ve discussed:

People from there are called lazy

Rife with disease

Very little infrastructure

The infrastructure that does exist gets destroyed frequently by the weather

Here’s a map of ethnicities in Colombia:

Basically the mountains in the middle are mostly mestizo or white, while the rainy, low-lying regions of west coast and the Amazon are Afro-colombian and indigenous respectively.

Meanwhile, the northwestern coast is actually somewhat populated. How come?

It doesn’t rain as much!

So we’re anecdotally seeing four factors directly affecting warm countries’ development in action

Rainfall: Extremely high around the equator, making farming nearly impossible, and hence big populations.

Disease: They affect the warm, humid, low-lying areas the most.

Mountains: People living higher up avoid so much rain and heat.

Sometimes, even close to the equator, some areas might not have as much rain, and the population is higher there than where it rains a lot.

Race: White people are especially prone to disease, so in these latitudes they tend to live in mountains. As we saw in the previous article, White presence is a market of development, even if we don’t know the causality (it can simply represent a higher transfer of human capital from the more developed Europe back then).

Now if we move east to Venezuela, it’s at the same latitude so we should see the same process. Do we?

This is a map of topography vs population density:

As you can see, most of the population is in the mountains. Caracas is at 900-1400 m of elevation.

Moving south, the same Colombian pattern of population can be found across the Andes, in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia:

As we discussed, this is where we find the only equatorial civilization that emerged independently in the world, the Incas.

As we move south and we enter temperate regions, the pattern reverses, and the populations appear on the lower plains of Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile.

If we move north from Colombia, towards Panama, we find the Darién Gap, a region so brutally rainy that there is still no road that connects these countries! The Pan American Highway, which reaches both polar seas and traverses virtually all climates across dozens of countries, can not close this 100 mile (160 km) gap.

This is a zoom in on the area:

And this is what the Darién Gap looks like on the ground:

You can see many of the things we’ve discussed here. The quantity of water is hostile. It creates rivers, it creates mud, it erodes the soil (hence the mud. Look at the exposed tree roots), the humidity brings disease…

This is where the Panama Canal was meant to be built, but the disease burden prevented it from happening. It was pushed north, but the construction still cost tens of thousands of lives from disease. This is Wikipedia on the French attempt to build the canal:

From the beginning, the French canal project faced difficulties. Although the Panama Canal needed to be only 40 percent as long as the Suez Canal, it was much more of an engineering challenge because of the combination of tropical rain forests, debilitating climate, the need for canal locks, and the lack of any ancient route to follow. Beginning with Armand Reclus in 1882, a series of principal engineers resigned in discouragement. The workers were unprepared for the conditions of the rainy season, during which the Chagres River, where the canal started, became a raging torrent, rising up to 10 m (33 ft). Workers had to continually widen the main cut through the mountain at Culebra and reduce the angles of the slopes to minimize landslides into the canal. The dense jungle was alive with venomous snakes, insects, and spiders, but the worst challenges were yellow fever, malaria, and other tropical diseases, which killed thousands of workers; by 1884, the death rate was over 200 per month. The French effort went bankrupt in 1889 after reportedly spending US$287,000,000 ($10 billion in 2024); an estimated 22,000 men died from disease and accidents, and the savings of 800,000 investors were lost.

As you move north across Central America, the pattern continues.

Across every country, the population gathers on the mountains, seldom on the plains.

Many of these mountains, by the way, are volcanoes.

We saw exactly the same thing in Mexico.

So, the two big empires to come from Latin America, the Incas and the Aztecs, were born in the mountains.2 Interestingly, in this entire area, the only other civilization to emerge was the Maya. Crucially:

The Maya lived in the driest parts of the region, as you can see on the map below

A sizable share of their settlements were on the mountains.

They were never a huge, centralized civilization.

They fell several times—maybe due to big rains and diseases?

If we look at a map of malaria prevalence in the region today, it won’t be a perfect reflection of historic conditions, because lots of work has been done to eradicate it, but here’s what we have:

It’s consistently prevalent on the biggest plains close to the equator.

Now look at this map, showing the risk of landslides in Central America:

This adds one more factor to our framework: Mountain societies also have to deal with landslides as an obstacle to development.

So that’s it for America. Let’s move on to Africa.

Let’s compare rainfall with topography and population:

There’s a ton going on here, so let’s break it down. We’re going to move quickly through the areas we visited in the original article and dive deeper into the more interesting ones.

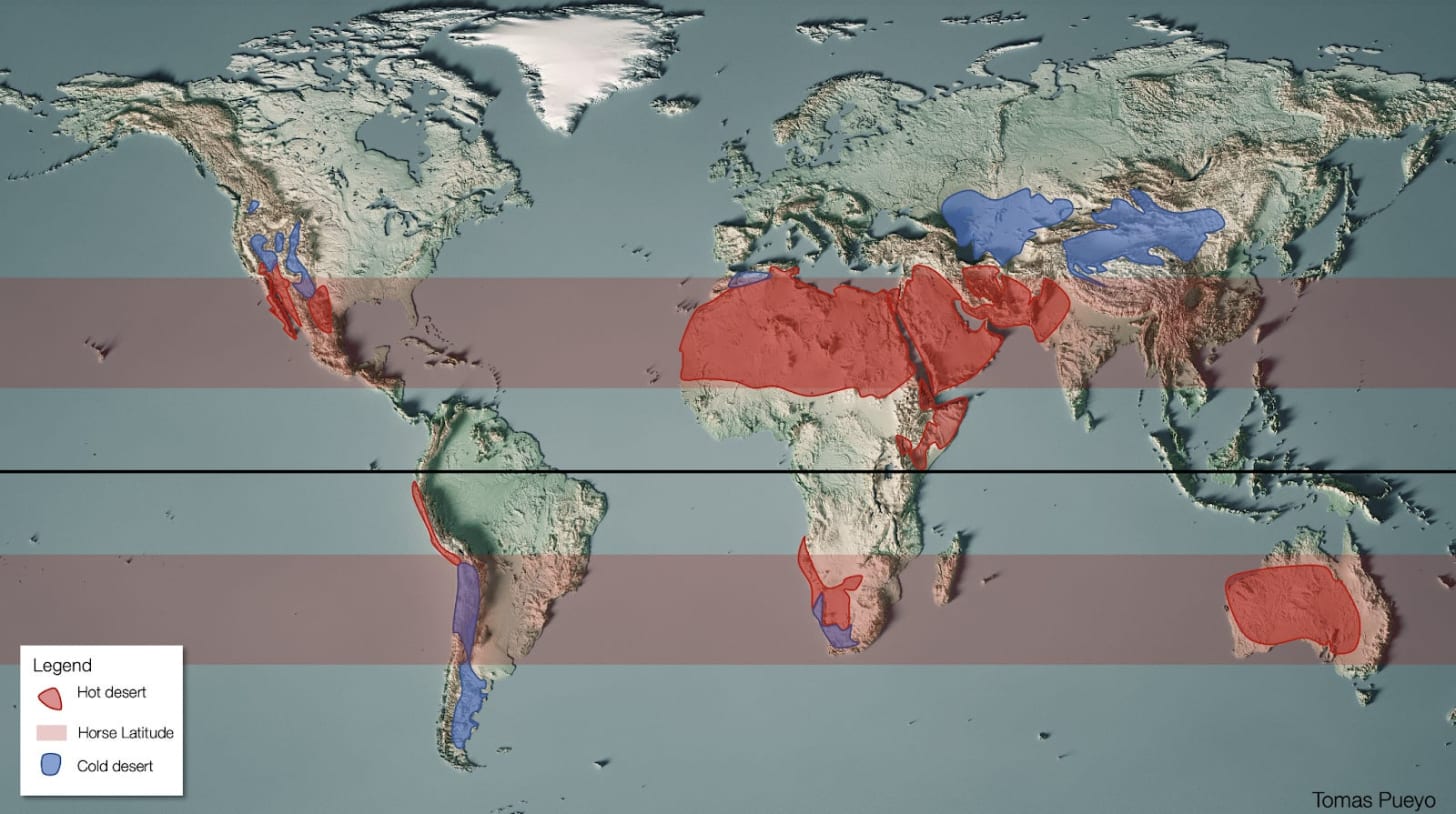

When there’s no rain, there’s no people. The Sahara, the Kalahari, and Somalia are empty. This is common in horse latitudes around the world, because of latitude and the atmosphere.

Ethiopia’s mountains catch the monsoon rains that would otherwise go to Somalia, so it’s cooler and rainier. That’s why it’s Africa’s 2nd most populous country.

The Rift Valley is the mountain chain that concentrates the most population in Africa... and it’s in the highlands.

The Maghreb in northwestern Africa is on the southern border of temperate regions. Mountains catch rainfall, and people live on them (as they’re more fertile) or on the coast, which is dry but includes the rivers from the mountains.

Let’s zoom in a bit on Egypt, which as we know is just the Nile.

It’s farther south than most other big ancient civilizations, which makes it a bit of an outlier. It’s quite warm. But it’s also extremely dry because it’s in the horse latitudes. The dryness means no diseases, and no leaching of soil from excessive rainfall. You still get the problem of lower productivity because of the heat, but does it matter here?

The heart of Egypt is the Nile, and it spawned a hugely successful civilization because it has lots of water flowing through flatland and so it fertilizes itself! In How Rivers Shaped States, we saw how the annual flooding of the Nile swamped the riverbanks with water and sediment. This is also why a very strong state emerged, as it was so easy to calculate the potential for food production of every plot (just note the high water mark), that taxation was simple. Crucially, the land didn’t require much work at all. Only during some key periods, so the productivity cost that comes from heat was bearable. It’s also why, I assume, the Egyptians could build the pyramids: There was so little work involved in agriculture that, outside of harvest times, the state could recruit this surplus of labor for its vanity projects.

So I’d say Egypt corresponds quite well to our theory.

The Congo is another country that corresponds perfectly. It’s the 2nd biggest country in Africa, but only the 4th in population. It’s 37th out of 54 in population density, and that’s despite basically occupying the entire Congo river basin!

The Congo River is the 2nd biggest in the world by discharge, basically the Amazon River of Africa.

Yet no big civilization has ever emerged here. Of course, the logic is the same as in the Amazon: too much rainfall, too much leaching, soils are bad for agriculture.

And the endemic diseases are terrible. Hence why most of the population in the region lives on cooler mountains.

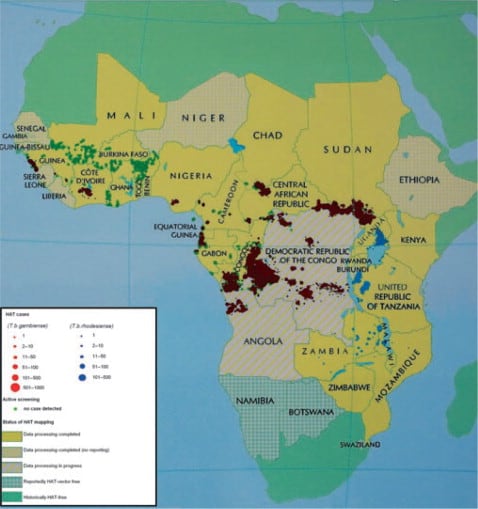

Now, adding malaria:

You can see most of the regions with big population centers tend to be in the mountains, where malaria is less problematic. The Congo is the most illustrative example, as it’s basically one big blob of malaria because it’s a large, low-lying, super wet, equatorial region. In comparison, the population centers in the highlands of the Rift Valley and Nigeria / Cameroon have the least malaria.

It is not the only disease. Here’s a map of trypanosomiasis, the sleeping sickness spread by the tsetse fly.

It thrives around the equator, especially in and around the Congo, and it doesn’t just incapacitate humans, but also big mammals. Spread by the tsetse fly, it kills essentially all horses and roughly 70–100% of cattle in the areas it inhabits.

Reader Rhea added this comment on Cameroon:

Douala, the metropolitan and extremely hot region, is considered lazier than the cooler mountainous city of Bamenda. I recall attending the state fair on a very hot day. I was exhausted and slow in mind and body. I recall a man telling my parents “it’s the heat, it affects the brain.”

So we’ve accounted for central Africa. There is, however, a big population center in a low-lying area of Africa that doesn’t fit our theory as well.

This is West Africa:

As you can see, from south to north it changes from jungle to savanna, then Sahel, and finally becomes the Sahara desert. Thus, it’s not surprising to see high population density in the savanna, sahel, and northern jungle:

It is not so flat:

Most of the major population centers are on these highlands. Here you can see the corresponding croplands:

Although this region has been populated for quite some time, it was never as populated as other world regions, and has never created a significant, lasting empire. The most famous ones are these:

They were all built around the Niger River, which has an inland delta, in the savanna and in the Sahel. This prevented it from creating the type of structure that exists in Egypt, which gets a single continuous river that reaches the sea and never dries up. Instead, most of these empires’ economic booms were not due to agriculture, but to gold and slaves. When the gold ran out, so did the empires.

But when you look at the mouth of the Niger, you see this:

Here:

It rains a lot. The latitude corresponds closely to that of the hyperrainy Colombian Pacific region.

It’s flat and coastal.

Yet it has cropland.

And it’s hyperpopulated today.

That said, by far the biggest crop in Nigeria today is cassava, which comes from America, a clue that suggests the population of this specific delta was likely not as high in the past.

Here’s my guess as to why:

Historically, this region was not nearly as populated as others like Egypt, India, China, or Europe. This is why it has not generated any significant empire.

It’s very close to other regions that don’t have as much rainfall and do have large population centers, so it can always be replenished by people from elsewhere when famine or disease strikes.

At the mouth of the Niger, it receives a ton of sediment to fertilize the land, so it has some agricultural productivity despite terrible soil (because it’s old and leached by rainfall).

It gets a lot of rain, but seasonally, from the monsoon, which means it’s not battered by daily leaching rains like the Amazon or the Congo, allowing some of that fertilizer to be retained.

It’s still rife with tropical diseases, which have hindered its development in the past.

The heat, humidity, and nearby mountains have probably hindered its productivity, so its GDP per capita has never been high.

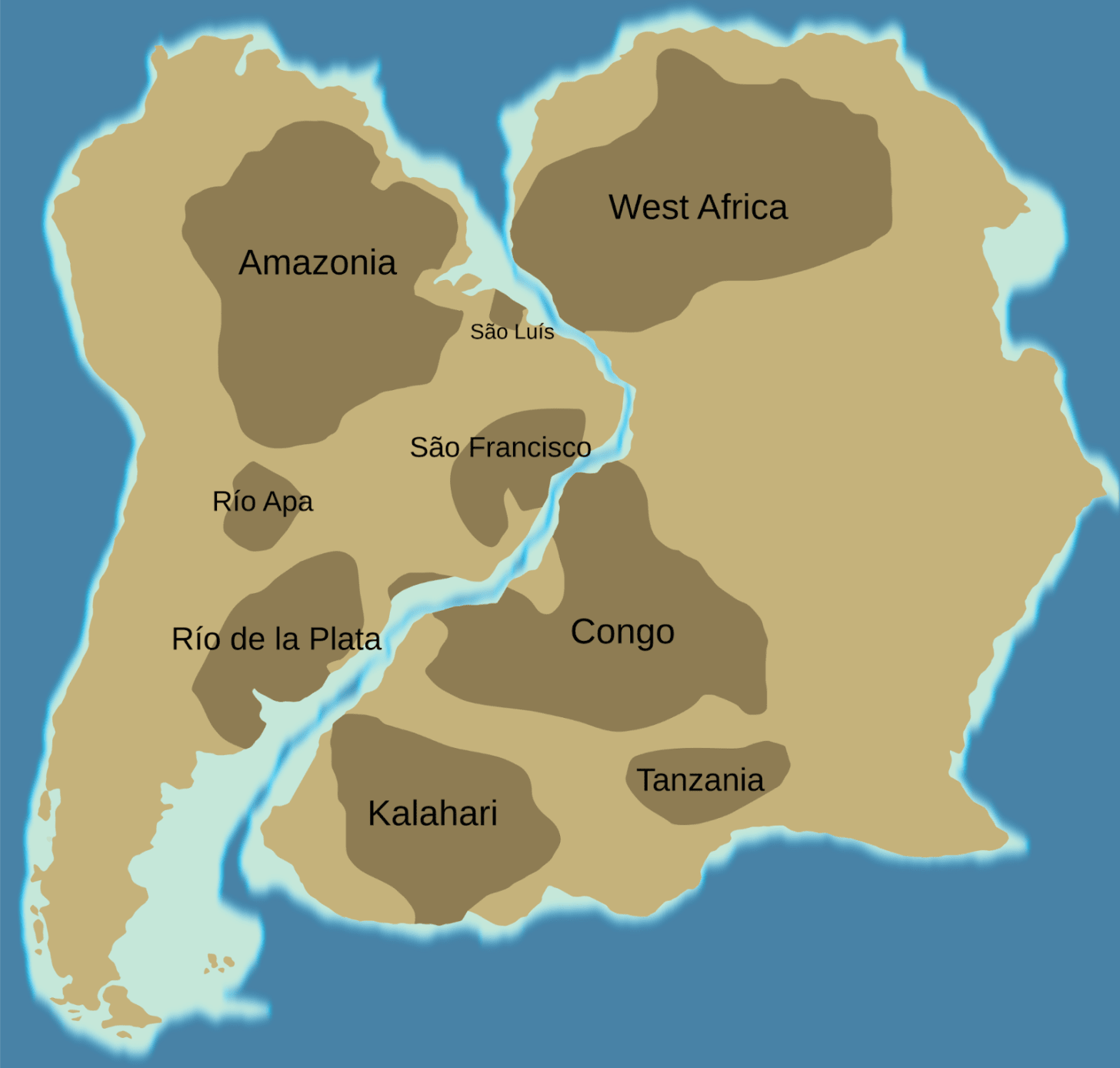

There’s one more thing that South America and Africa share.

Parts of both continents are very old, so their soil has been leached for eons, making it quite poor for agriculture. Yet another reason it was hard for big civilizations to emerge there.

I’ve never mentioned Madagascar, but it’s a pretty good illustration of the dynamics we’re discussing, so here it is:

The highest density is in the mountains, there’s a secondary center of population on the windward coast (which gets more rain), and all regions are quite poor.

OK so I think we’ve got a good sense of what’s happening in Africa. Let’s move to Oceania, and then finally to Asia.

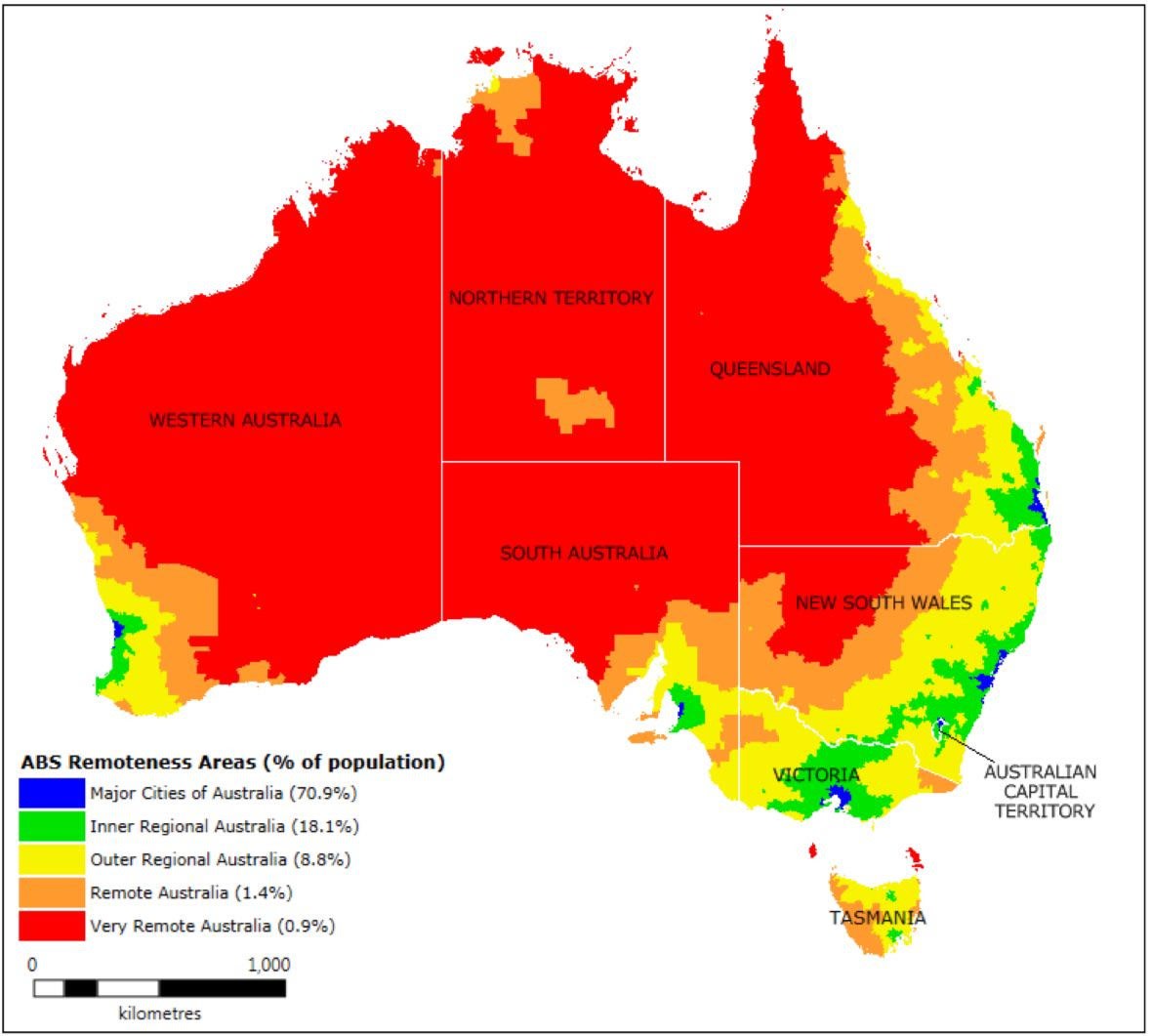

There are many examples here that illustrate our theory, starting with Australia.

From the previous article on the topic, from a commenter:

By area it is mostly a hot desert, but its institutions and GDP have flourished on its temperate southern coast and the entire country has benefitted from them.

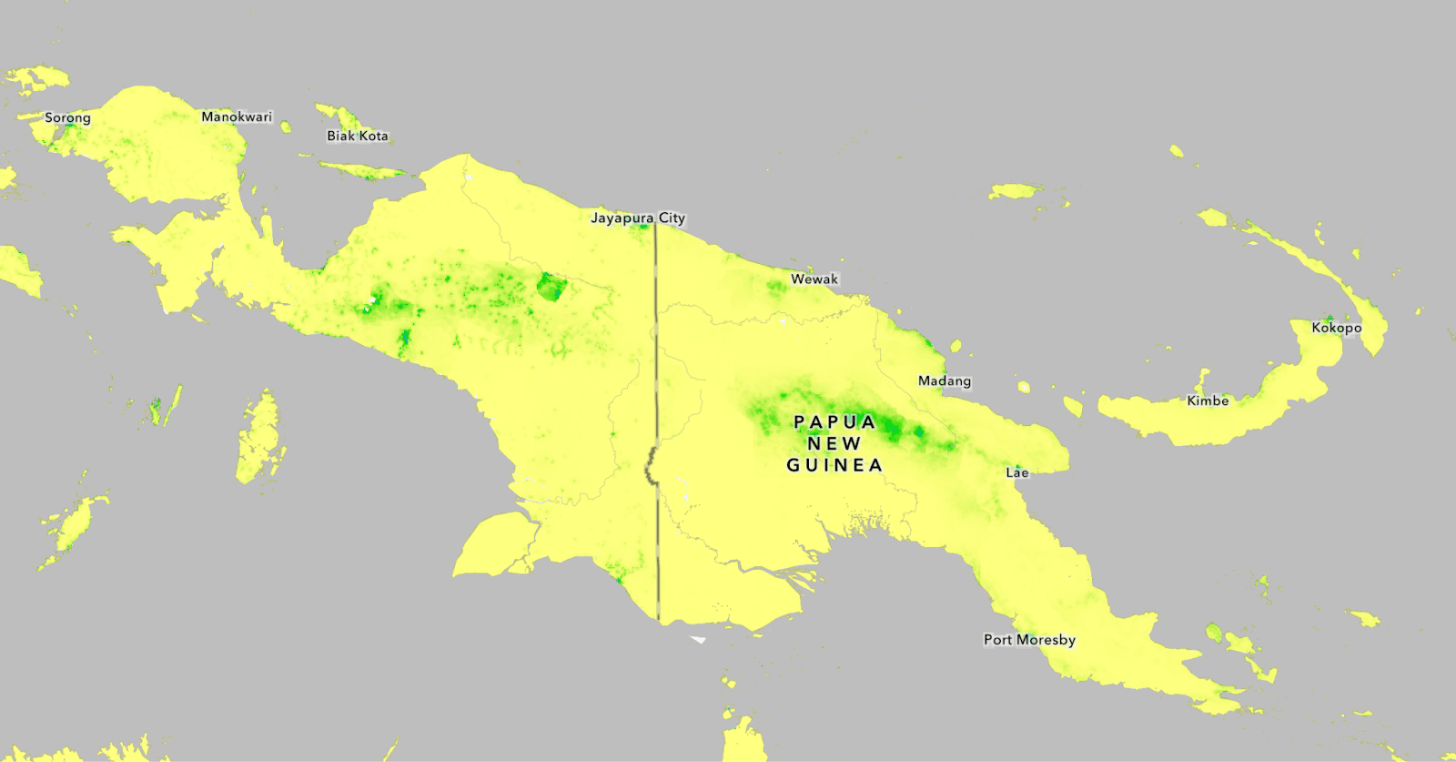

An equatorial island with flatlands and mountains down the middle. Where do people live?

Yeah, mostly on the mountains.

Malaria, however, is exactly where you’d guess.

New Guinea is also famous for its unbelievable diversity (hundreds of languages!) and its corresponding proclivity to conflict.

This is the poster child. New Guinea is tropical, mountainous, poor, multicultural, and prone to diseases in lowlands and conflicts in highlands.

But in the same region, there’s one big outlier that seemingly defeats the theory.

Java, with 156 M people, has a bigger population than Russia. From the article on the island:

Java’s population density is 1,100 people per square km.

This is 3x the density of Japan or the Philippines, 7x that of China, 30x that of the US. It’s nearly the density of Houston, Texas. For an entire island! With volcanoes!

Even weirder: Its neighboring islands in Indonesia are not that densely populated.

Compared to its biggest neighboring islands, it’s 8x more densely populated than Sumatra and 30x more than Borneo!

Why!? What made this island so special?

The answer is volcanoes.

Basically all the islands in the region are like Congo or the Amazon rainforest: They have massive amounts of rain leaching the soil, and they can’t easily farm anything. But the ash from Java’s volcanoes constantly fertilizes the soil there, making it incredibly productive.3

This is why it’s so populated today, but this is a reasonably recent phenomenon. Back in the 1800s, its population was smaller than Germany, France, or the UK.

This is also true of other countries like Thailand, Malaysia, or the Philippines (which also benefits from volcanic fertility, but without the equatorial leaching rains). In fact, it’s time for us to move on to the most important region, Asia.

We discussed in the original article on Mountains how Iran embodies the theory perfectly.

But of course, neighboring Turkey also does. Its capital, Ankara, is at 1,000 m altitude (~3,000 ft).

Afghanistan never had a big enough population to create a strong local civilization because it’s too elevated and dry.

But it’s a good example of some of the dynamics we have discussed. Infrastructure is very hard. As a commenter said:

Seasonal rains have been known to completely destroy bridges—not destroying the bridge itself, but by washing out the approaches, leaving the bridge perfectly intact in the middle of a new wider river.

He also added that balkanization is intense here.

China is a poster child of our theories.

Its heartland is in the north—the perfectly temperate North China Plain. Over time, China conquered the south little by little. But the farther it went, the harder it was, as it confronted more mountains, mosquitoes, and malaria. It took the north a very long time to finalize dominion over the south, and even today, the mountainous Yunnan region has about 50M people, who are still ethnically different from the Han, and politically remote. In that region, you start seeing communities on plateaus that you don’t see in the north—like the capital, Kunming.

Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia are also quite informative.

Lots of mountains and jungle here, but wherever you have a big valley with a river, you also have a decently-sized civilization today.

So it doesn’t look like this is close enough to the equator for populations to grow better in mountains. But also this region doesn’t have elevated plateaus, so we don’t have a counterfactual example. What we can tell, however, is that the farther south you go, the less population there tends to be:

The Malay peninsula, farthest south, is not very populated.

In Vietnam, the south has the Mekong River valley and delta, and they’re much bigger than the north’s Red River valley and delta. However, the Red’s valley is much more populated than the Mekong’s in Vietnam.4

The valley of the Chao Phraya in Thailand, which extends into Cambodia, is huge, yet in the past its population wasn’t as massive as China’s.

If we look at rains in the region:

It seems like a key condition is to not have rain year-round. The tip of the Malay Peninsula, like the islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea, have rain year-round, and none are highly populated. We saw the same pattern in America (e.g. the Darién Gap), and Congo vs Nigeria.

Interestingly, a similar pattern can be seen in the Philippines: The northernmost large island (Luzon) is much more densely populated than the southernmost large one (Mindanao). Within Mindanao, the least populated part is the east coast, which receives rains virtually all year long.

Also, we can see how Java is actually south enough to get at least some dry season across the majority of the island.

There have been a couple of empires in this region in the past, the Khmer in Cambodia, Siam in Thailand, Burma, and Vietnam. But most of these only emerged in the 1200s or later, and none had big populations. The Khmer, in Cambodia, emerged earlier, but their apogee was also in the 1200s, and its population didn’t even reach 1M back then (700k-900k). For comparison, Rome 1,000 years earlier had 60M-75M, similar to China’s and India’s. Egypt had 4-8M thousands of years earlier.

This leads us to our final destination.

India is a mix of everything we’ve seen.

Most of the population is actually in the north:

It follows the Ganges River Valley. The population in the rest of the country is less dense. But it also tends to live more on mountains!

Bangalore, for example, one of the southernmost big cities in India, is 1,000 m (~ 3,000 ft) high.

Also, if you go back to the animation of rainfall throughout the year, you’ll notice the long annual periods of drought, which make sense since most of the country occupies similar latitudes to Arabia and the Sahara desert. But the drought periods are followed by the intense monsoon that then brings sediments down to fertilize the Ganges Valley. This wet-dry cycle reduces soil leaching and diseases.

If we summarize:

Temperate means population and wealth.

The most prolific societies have tended to develop in the yellow / brownish / green areas below: US, Canada, Mesoamerica, Incas, Argentina / Chile, Europe, the Atlas / Maghreb, South Africa, the Rift Valley, Ethiopia, Levant, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Persia, China, Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand…

Even in smaller countries, we see a similar pattern where people tend to live in cooler mountains than on the coasts, like Madagascar, Cameroon, and New Guinea.

Near the equator, there are few, poor people

This is because the intense, continuous heat produces intense, continuous rains, which in turn leach soils and cause disease. This is why populations and wealth have been very limited in the Amazon Rainforest, any low-lying region in Central America, the Congo, Malaysia, Indonesia, and most of New Guinea.

In my previous post, I had not noted the importance of constant rains and their consequence:

Lots of soil leaching, so little agriculture, so little food, and fewer people

Even more disease than elsewhere, imposing a productivity toll

Exceptions are rare and very telling. The main one is Java, which fights the leaching through volcano ash. Another is the Niger Delta in Nigeria, which seems to have developed recently, has a dry season, and is fertilized by the Niger’s sediments.

The transition between equatorial and temperate climates creates unique situations based on local conditions, so you have to pay attention

Here, there aren’t constant rains anymore, so leaching and disease are less prevalent. It’s still hot, so elevated plateaus in these regions did give birth to civilizations (e.g., Mesoamerica, Iran, Anatolia). But they aren’t necessary for civilizations to emerge:

Egypt is hot but it doesn’t have any leaching, and the burden of disease is low thanks to the year-long dryness of the environment. Fertilizer is brought by the Nile.

In Indochina, there’s more development as you move north. The southern tip gets year-long rains, and has very little population. All regions that developed have strong fertilization via rivers (which brought the sediments leached by the seasonal local monsoon). The civilizations that did emerge did so later, with smaller populations than in other regions, probably due to the harder conditions.

India has both a dry and a wet season. The north is the most populous. It also happens to have the Ganges (and the Indus in Pakistan), a great, year-long source of water and fertilization. The south is more mountainous, and the elevated regions are quite populated. My guess is that heat and disease burden have hindered the country along its history, even if not enough to stop it from becoming so populous.

This also brings us back to Malthus and the sources of wealth. Today, we’ve mixed GDP with GDP per capita, because of the Malthusian idea that more wealth meant more people. But this is not completely accurate.

Agricultural productivity used to be the determining factor of civilizations, because virtually all the economy was focused around food. So everything we said today is relevant broadly until the Industrial Revolution. For agriculture, heat and humidity are fantastic, but leaching and disease are not. This is why, until the 19th century, the poorer regions were those very close to the equator, where leaching and disease were the worst.

This also means there is a discontinuity in agricultural productivity: It’s really bad close to the equator, but the more humans escaped year-long rains—which happens around both tropics—agricultural conditions quickly improve. This is why wealth measured as people or GDP is more common in warm countries than GDP per capita.

That was before the Industrial Revolution. Afterwards, the productivity of agriculture matters less. And outside of agriculture, leaching doesn’t matter at all, but disease and human productivity still do. So temperature and humidity have hindered the rest of the economy. This has happened a lot directly, but also by pushing people to live in the mountains. This factor is more continuous than leaching though, so the farther from the equator, the better.

I would also like to add some theories from commenters, which I haven’t independently verified but sound reasonable:

Steven Weisz argues that more seasonal variance requires more planning, which in turns begets more human capital development to make it happen, and probably a more adapted culture and institutions.

Al MacDonald suggests that people living in the mountains have less oxygen, which might make it harder to exert yourself.

If we add up everything, this is what we get:

I hope you took advantage of the holidays to read and enjoy this massive article! Next week, we’ll be back to close 2025 with a retrospective of two topics we’ve explored during the year: Robotaxis and AI. I’m extremely excited about what comes next, which I’ll share very soon. In the meantime, merry Christmas and happy holidays!

And maybe a bit of the oil & gas regions of Russia.

Tellingly, the earliest predecessors to the Aztecs were the Olmecs, on the coast, but their civilization was never as rich or populated. Teotihuacan followed, and it was much bigger and powerful—and on the mountains.

Unsurprisingly, many of its biggest cities are nested around volcanoes, like Bandung or Malang.

I’m going to guess this is an underdiscussed reason why the north beat the south in the Vietnam War.

2025-12-20 21:02:33

Lots of interesting stuff, just jump to what’s interesting to you! Today:

Were the Dark Ages actually dark?

What we’ve learned about US history: civilizations older than Egypt, super early settlements, the role of silver in the US’s independence, how the US kick-started its industries, and how that influenced the North-South war.

When Spain wanted to conqu…

2025-12-19 01:34:12

This is the quarterly review of all the new learnings on GeoHistory topics we’ve covered.

Today:

The Future of Nation-States: How countries are overspending and trying to tax the rich, who flee, while state control is becoming flimsier by the day.

Cities: A new one, what we’ve learned about the existing ones, SF, and how specialized cities must be to thrive.

The latest on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Hint: Not looking good for the long term.

Later this week (premium):

Were the Dark Ages dark?

What we’ve learned about US history

When Spain wanted to conquer China

The importance of transportation

And more

One of the big themes of Uncharted Territories is how the entitlements that Western countries have committed to are incompatible with the wealth concentration and uprooting allowed by the Internet, AI, and crypto. Overspending states will try to tax rich people, but these are quite mobile, and therefore, hard to tax. Recent news has been confirming this thesis.

In Europe, if a company pays €60k per year for your services, how much of that do you keep?

In countries like France or Italy, you barely keep 40%. Most of what you make goes to the government! How much more can they tax? I argue not that much. They’ve already maxed out what they can take.

Of course, they’ll try to get more, and the go-to victim is rich people. Alas.

Storonsky is just one example of many.

This follows a recent increase in UK capital gains taxes, from 10% to 18% for standard gains, and from 20% to 24% for high earners.

Quick back-of-the-envelope calculation of the ROI of this move:

Storonsky owns 18% of Revolut.

Say it’s worth $200B when it goes public.

That’s $36B ownership.

If he were to sell, the UK capital gains bill on this would be 24%, or $8.5BN.

In the UAE, it will be $0.

Over 8 billion dollars for a change of residence sounds like a nice ROI. For Storonsky. For the UK, it’s devastating. But it’s just the beginning of their weakening grip.

States control the land. If something is connected to the land, states can track it, demand payments, and send their guns to enforce their demands. So real estate, energy generation and transmission lines, airports, roads, telecom cables… All of these are their tools of power. Tools like remote work and solar energy are their enemies.

SpaceX’s Starlink is the tool that will untether communications. And they’ve recently moved one step closer to this vision: As I mentioned recently, they’ve just trademarked “Starlink Mobile” and they’ve bought a bunch of mobile spectrum to operate in the US—probably the first of many countries for which they will do this.

Can states still control telecommunications in this scenario? What if, say, a country like Iran tried to block mobile access the way they tried to block Starlink Internet?

For a direct satellite-to-cell operation to work, you need the satellites, the frequencies to emit the communication, the devices, and some land facilities like network operations centers and gateways.

Governments like Iran can’t control the satellites. They will be able to emit in this new spectrum (the range of frequencies Starlink just bought) in 2 years.

Devices need to be able to handle the same spectrum. Today, phones don’t support the spectrum SpaceX has bought, but SpaceX is working on phone makers enabling it. Musk claims it will also be a reality in two years.

Theoretically, governments could block the sale or ownership of enabled devices, but it would take a forward-thinking government to do this. I guess China could do it, but I’m skeptical any other will.

Alternatively, Starlink could bypass this by illegally using spectrum it doesn’t own, if no other company is using it. I assume, as a rule of thumb, most countries have more spectrum than they’re using. If Musk is forward-thinking, he will enable satellites to handle a broad array of frequencies.

Countries could jam the frequencies Starlink uses, but that would cost billions of dollars in jammers. It would probably only be possible in big cities, so people who want to bypass their government’s control would simply live elsewhere.

These don’t need to be in any specific country, they can be in neighboring ones, so no control here.

That leaves physical control as the only tool states have to control direct-to-cell communications. It’s basically like what Iran did to suppress Starlink Internet during the war with Israel, trying to jam the satellite internet in urban areas, and spot and confiscate the devices. I’m sure they caught some people, but I doubt they suppressed it. With direct-to-cell, it’s the same thing, except there are no dishes to spot, only phones. And you have to be able to distinguish satellite connected phones from the rest. Almost impossible.

Note that none of this applies to a country like the US, though, because the US controls SpaceX, but also Apple, Google, Qualcomm… It could intervene at any of these layers. But this state capacity is not shared by most other states. Overall, it sounds to me like this will dramatically undermine the power of most1 nation-states: They won’t be able to stop their citizens from communicating anymore!

Another big consequence of the End of Nation-States is that all citizens will be able to understand each other better, so ideas will flow across countries, and people from different countries will feel much more like each other than today. A few years ago, I thought this would happen through everyone learning English, but I’m less and less sure. It looks like AI translation is becoming frictionless faster than people are learning English.

With direct-to-cell communication, people won’t even need a Starlink device to surf the web or talk to anyone, anywhere on Earth. And the grip of governments will grow even looser still.

The pattern that emerges from the 40 or so articles I’ve written about cities is that there’s a science behind the good ones, but we’re mostly unaware of it. We don’t know what makes cities appear and thrive. So every time we discover a new factor, I pay attention. Like noise.

How do you quantify the cost of noise to society? This paper did it intelligently: It looked at how much people were willing to pay to live in a calmer area. How? They looked at the prices of homes along noisy thoroughfares before and after the construction of noise barriers.2 After they were built, prices became 7% higher than in areas with no noise barriers. In other words, people were willing to pay a 7% premium to live in less noisy areas. Researchers estimated that, considering all the real estate value across the US, the cost of noise was $110B! What would be the equivalent cost if applied to cars? Nearly $1,000 per car per year! That’s what cars should pay on average if they covered their externality, the negative impact of their noisy existence.

Luckily, electric vehicle engines barely make any noise, so their use will improve the quality of life in cities. However, that’s only true at low speeds:

Starting at ~40-50 km/h (~25 mph), most of the noise a car makes comes from the rolling, not the engine roaring. For trucks, that comes later, at around 60 km/h (~40 mph). Which means that small roads and streets will have much less noise than today, but highways won’t.

The amazing Jan Sramek and his California Forever are building the most exciting new city in the West. They’ve just submitted concrete plans for incorporation.

It will include Solano Foundry (America’s largest manufacturing park), Solano Shipyard (the largest shipyard3), and walkable neighborhoods for 400,000 Californians.

I’ve talked with Jan in the past. He’s one of the most joyful, optimistic, intelligent, driven founders I know. His vision is very ambitious.

More importantly, I think his plan will work. He’s been at it for a long time, and the last time we spoke, it seemed like he had finally figured out how to navigate the political side of city-building.

More on this plan here.

This new paper looked at a measure they called coherence: How concentrated cities’ economies are.4 They found that big cities are well diversified, but small cities’ economies are not. Those tended to be highly concentrated in one or a few industries. As cities grow, however, they diversify, for example, moving from craftsmanship to engineering and manufacturing.

This resonates strongly with everything we’ve seen in Uncharted Territories: Unmistakably, big cities today started as specialized small cities. These specializations tended to be around trade. For example, since Chicago is the trading hub between the Mississippi Basin and the Great Lakes, it specialized in the transportation and trade of the local commodities: beef, wheat, corn, and timber. From there, it started diversifying into more and more industries.

This has a lesson for new cities: You gotta have some specific industry you’re catering to, and focus all your attention on that. The more concentrated your industry cluster, the stronger you will be.

The only cities that should focus on diversification are those that are quite big, but still heavily concentrated in too few industries. Dubai went from oil to transportation, from there to trade (of the transported goods), to finance (of the trades), and from there to other industries like real estate, healthcare, and education. Detroit and Pittsburgh were not diversified enough, and they suffered when their industries collapsed.

In light of this, is California Forever’s plan a good one? I guess the manufacturing foundry and shipyard make sense, but are they similar enough to feed each other? Maybe it’s too diversified already? What makes CF unique is that it’s a satellite city (to San Francisco and Sacramento), so it could quickly attract enough people to cater to both industries. Maybe that makes the double focus sensible. What do you think?

Speaking of California cities, I love this image.

In my 10-part series on Israel and Palestine, I concluded that the conflict would only be resolved when Palestinians wanted peace. So how’s that going?

The Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), a pretty neutral Palestinian non-profit, has just released an update to its polls.

A majority of Palestinians support Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7th 2023.

When you look at Gaza, you could see a huge support just after the events, but support cratered as Israel methodically destroyed Hamas, and with it Gaza.

It seems like support is increasing as things have calmed down.

What would you conclude from this?

One could imagine most Palestinians being against the original attack, and as Israeli destruction has rained upon them, their hatred and desire for vengeance would have increased. Instead, we’re seeing the opposite: They supported Hamas… As long as they thought it was winning. As it appeared to lose, support cratered. Now that it seems like they might survive in power, their support increases. Might makes right.

If this were true, and we took it to its logical conclusion, the end of the conflict will only come when one of the two sides fully prevails.

Let’s see more data from that report. More than half of Palestinians don’t support the two-state solution.

This means that what they support is Arab Palestinians controlling the entire region, as in the elimination of Israel. 40% still support armed struggle.

If that sounds radical to you, note that this is a pretty typical interview with Palestinians.5

Ergo there won’t be peace in Palestine.

The Arab / Hashemite king of Jordan, who is no friend of the Palestinian leadership—because after the country hosted them, they tried to organize a revolution—thinks no international peace troops will ever enforce non-violence in Gaza.

So my hopes on the conflict remain as high as ever: There will be no peace in Palestine in the next few years and decades.

I hope at some point, my idea of intervening in Palestinian (and Israeli) education and culture won’t seem so naive. It’s either destruction or reeducation.

China, and maybe some other high-state-capacity countries, might also be able to.

It controls for other aspects by looking at barrier construction events, and comparing the places where barriers were not erected on that road vs other places where they were. There’s obviously a small confounding factor but I think it’s probably minimal.

In terms of land surface, it will be more than twice as big as the 2nd in the US.

They measured this through data like how closely related the industries of random pairs of workers were.

This comes from The Ask Project, which has hundreds of videos like this. I’ve seen many dozens, and this is the norm, not an outlier. I don’t understand Arabic so I can’t judge that part, but the English part is quite unbiased. I’ve watched dozens of interviews with Israelis too, and the questions are usually quite similar, if not identical, and the pushback seems equivalent on both sides. It also corresponds to the interviews I carried out myself in the West Bank. So unless somebody brings evidence, I will consider The Ask Project quite unbiased, and those attacking it without data as biased.

2025-12-12 22:57:31

It’s time for the quarterly magazine. In the coming days, I’ll be sending a few smaller-than-usual articles on all the news relevant to topics we’ve covered in Uncharted Territories. Today, I’ll share eight thoughts on a topic I’ve touched in many conversations behind doors across the world this quarter: the shifting of power between China, the US, Russia, and the EU.

After the Network States Conference this year (I’ll write about it in the future), I went to visit Srinivasan at his Network School in Forest City, which I’ll talk about another day. As we walked around the city, we spoke at length about the future of the world. He had an interesting take: In the war with Ukraine, China will keep supporting Russia for as long as it takes.

In China’s view, it’s the perfect conflict:

The US must focus on Europe, preventing its shift to China.

It sinks Europe’s time, attention, and money.

Russia loses power, population, resources, reputation, and wealth, making it immensely dependent on China.

The longer the conflict rages, the more Russia unties itself from Europe, and so the more it must tie itself to China.

This is why Balaji predicted Russia was eventually going to prevail, or at least not lose.

Meanwhile, I had the same take on the other side. It’s unknown whether the US will continue supporting Ukraine, but if it doesn’t, I really think Europe will pick up the slack: Whereas the US’s support in Ukraine is largely a symbol of its power, for Europe it’s not a symbol, it’s very much a life-or-death situation, as illustrated by very recent history:

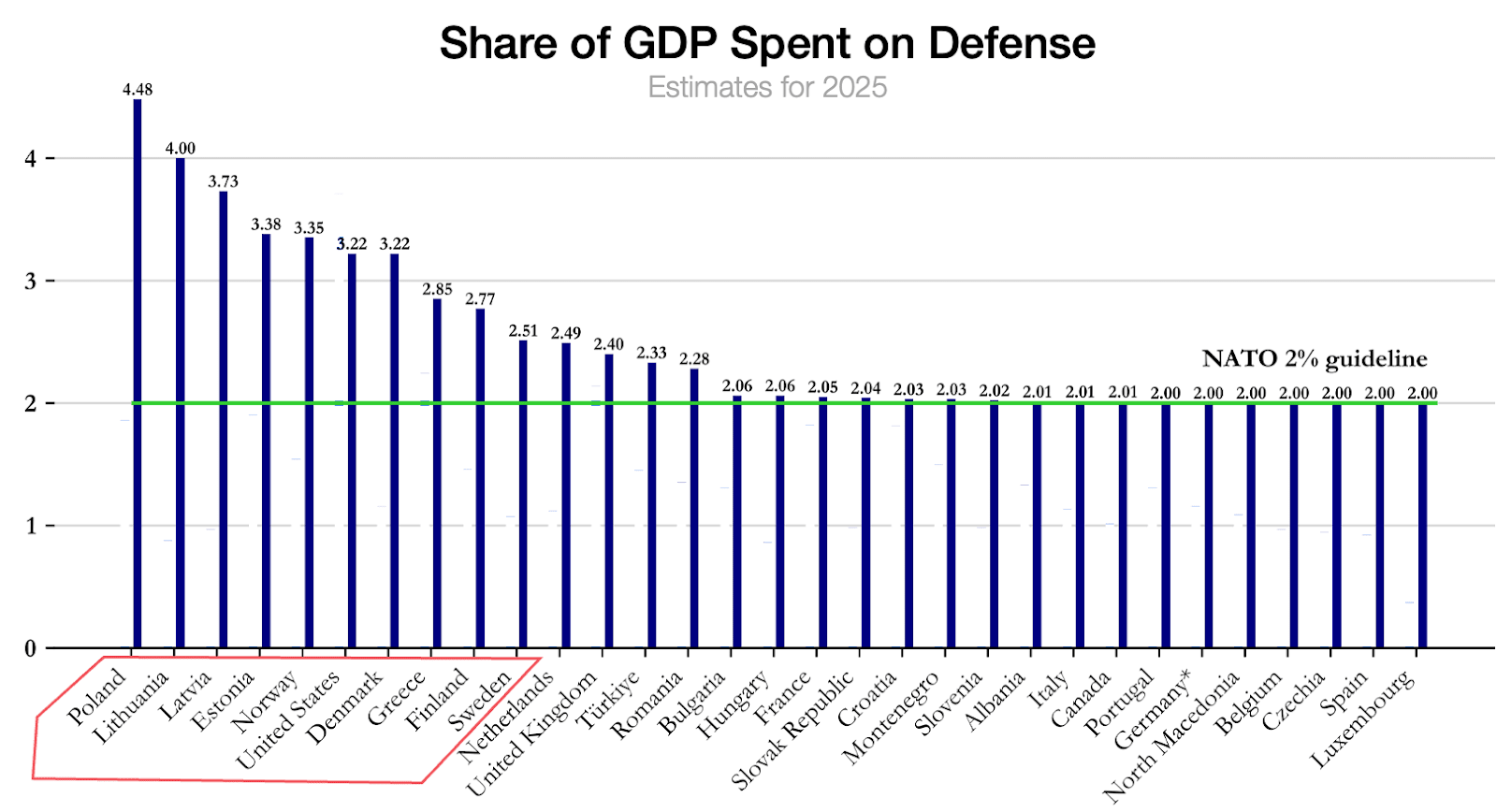

Hence the fact that now the US is only the 6th biggest spender on defense in the NATO alliance as a share of GDP, and all the biggest spenders share borders with Russia.1

This does not bode well for the war between Russia and Ukraine, which by the end of January 2026 will have lasted longer than Russia’s involvement in WW2. Prepare for a long war of attrition. Exactly what’s convenient for China.

As we explained in this article, Russia already has a very weak grip on the eastern side of its empire, Siberia: It’s far from the capital, and transportation is inefficient between east and west.

And that grip is going to weaken as Russia weakens:

Because of the war with Ukraine

It has had a poor fertility rate for a long time already, with a population that’s been shrinking for decades

Most of its economy and government run on oil and gas revenues, which will soon disappear (I’ll talk about this in a future article)

Meanwhile, it’s not news that China is becoming stronger, and as we said, Russia is growing more dependent on China.

I found this tweet interesting:

What are these territories the Qing was forced to surrender to Tsarist Russia?

Would it stop there? I don’t think so. The same way Tsarist Russia took advantage of its superior power to take over some regions of Chinese influence, so would China do the same in the reverse situation. And it already has an excuse

Translated with this

This video, circulating in China with millions of views, claims that if Russia loses the war in Ukraine and disintegrates like it did in the 1980s, China should march northwards and take over parts of Siberia, because otherwise the US would do it, and that would be too threatening for China.

I found myself at another conference a few weeks ago, talking in private about different people’s perspectives on China: diplomats, investors, politicians, entrepreneurs… They shared some ideas anonymously, so here they are.

China annexed Tibet 75 years ago. It is in the process of assimilating the Uyghurs from western China. Now that the US has vacated Afghanistan, China is increasing its influence there. A very well connected source in Afghanistan told me they are feeling a heavy Chinese presence on the ground.

A US diplomat said something very interesting about China’s economic prospects:

There’s this Russian saying: “In Russia, if you have money and no power, you have no money.”

The same is true in China. The only way to allocate capital well is for the private market to do it, as it has much more information and its incentives are better aligned than the government’s. But for private markets to allocate money, they need to be sure that money will remain theirs, have long-term assurances that the government won’t take it. This would mean the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would have to relinquish power (the power to seize economic assets and redirect the economy). The CCP will never do that, so the private market won’t invest efficiently.

I thought the Belt and Road Initiative (a global economic and infrastructure strategy to connect China with its trade partners) was shrinking every year, but no, that was a COVID thing. It’s reaching new records:

Initially, I thought it was destined to fail: So much money hastily invested around the world could only fail. I’ve changed my mind. These investments make a lot of sense:

They increase China’s influence around the world.

They increase China’s military presence around the world.

They allow it to bypass US choke points in the sea, notably the Strait of Malacca, through which most of China’s oil circulates.

China has construction overcapacity. These deals allow the country to keep building with this overcapacity.

They diversify China’s investments.

This is especially valuable because China used to buy a lot of US debt with its trade surplus, but that made it dependent on the US, so China has been shrinking its US treasuries for over a decade.

A US investor in Africa said something that I had never heard before:

Chinese people go to Africa because they say competition is lower. Everybody works extremely hard in China and has a lot of education. They’re competing for the same jobs. They say they have no competition in Africa because, according to them, “Africans are lazy and dumb.”

It reminded me of the documentary Empire of Dust, in which a Chinese contractor complained about how the Congolese behaved at work and in managing their infrastructure. Some excerpts here:

This highlights how Chinese investment and infrastructure will continue in the future, but also points at conflict: Economic power in the region will have to come with political power, but the last time foreigners had a strong economic and political footprint in the region, it didn’t go so well.

Meanwhile, according to a diplomat in Africa, China so far has utterly failed at conquering the hearts of Africans. They all consume US media, follow US or European sports, sing and dance to English songs, and all aspire to move to America or Europe. I’m not sure of the best way to win this battle of hearts: The US approach of making movies like Black Panther and fighting for the rights of Black people (think Black Lives Matter), or the Chinese approach of building infrastructure while berating Africans for their stupidity.

Why does this matter?

Here’s one visceral way to convey China’s demographic crash:

Contrary to many people’s beliefs, I think the US got better thanks to the competition with the USSR.

Usually, we remember the bad (especially the wars, like in Korea or Vietnam, or McCarthyism), more than the good. But there was more good. And not limited to the space race. Thanks to the competition with the USSR, the US had to make efforts to compete in ideology. It was more egalitarian, progressed more in welfare, and focused on the shiny city on the mountain more than MAGA. It courted international friends instead of putting America First. It cared more for the world and making better international institutions.

Since 1991, the US has had no rival, and the result has been more inequality, deindustrialization, less attention to international organizations, more political polarization…

But since China’s power has grown, the US is shining in the areas where there’s most competition. It’s trying to reindustrialize (eg, Build Back Better), invests heavily in AI, has given a legal framework to crypto… And we can expect the US to become a beacon of freedom in opposition to China’s authoritarianism.

Conversely, China’s century of humiliation was caused by its backwardness, which in turn was due to the fact that it had no rival in the region.

Competition is good.

Except for Greece, which has always had a big military spend to fend off Turkey. Note that Finland and Sweden were not even in NATO before the war.

2025-12-10 02:18:37

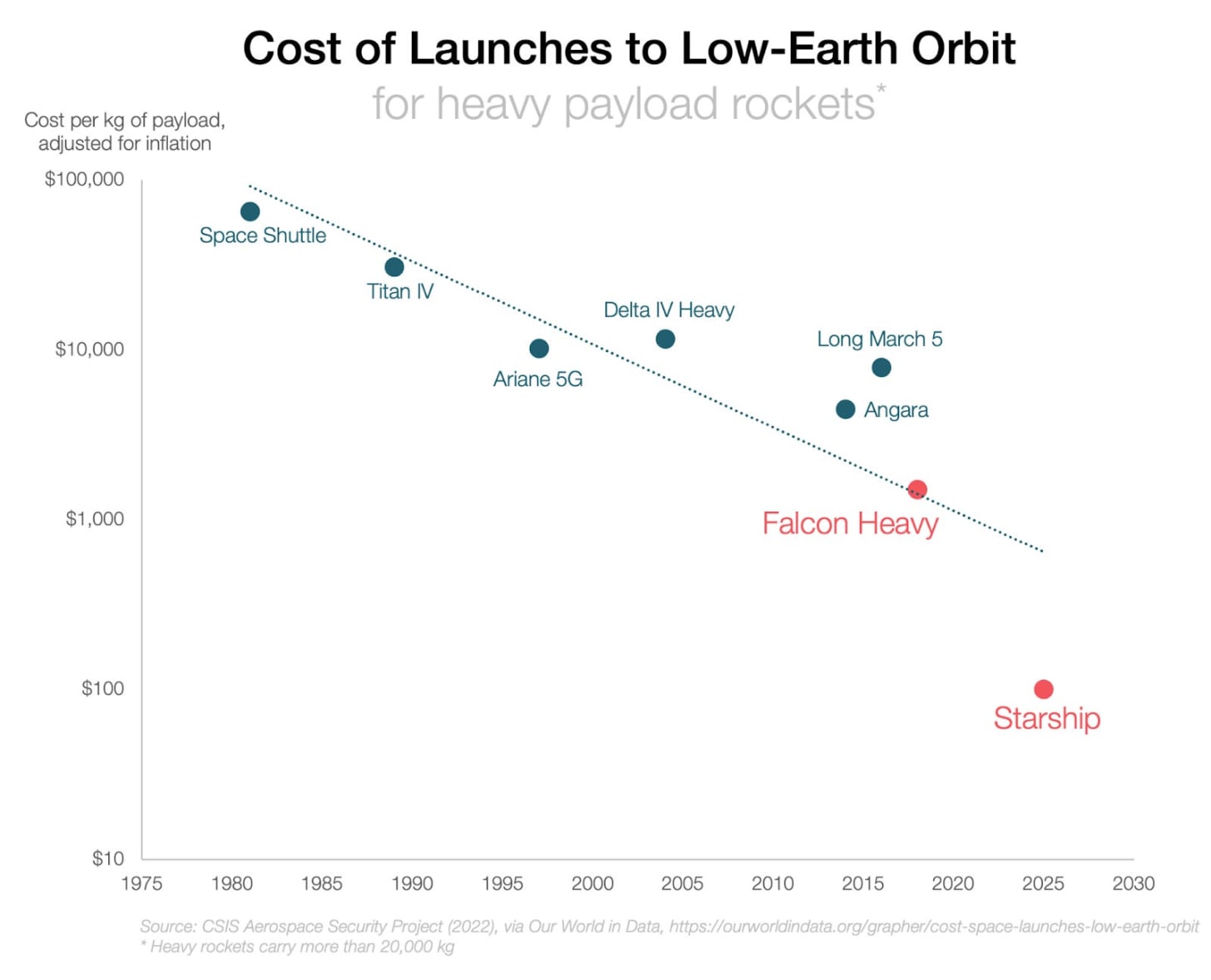

In Starship Will Change Humanity Soon, we saw how the cost of sending stuff to space is dropping, and that will enable new industries to emerge.

In No Room for Deep Space, we realized most of these industries will be close to the Earth, including space tourism, Earth imagery, space mining & manufacturing… Now, we’re getting specific examples of this.

Of course, the biggest example is SpaceX’s Starlink, which has just trademarked “Starlink Mobile” and it has bought a bunch of mobile spectrum to operate in the US—probably the first of many countries for which they will do this. This is leading SpaceX to a valuation of $800B.

But today, I want to look at less well-known examples:

Helium on the Moon

Pharma manufacturing

AI Data Centers

In No Room for Deep Space, I said it was not economically viable to mine anything far from Earth:

Let’s assume the cost of transportation to space is $5,000/kg, and mining there costs an additional $5,000/kg. That’s a total of $10k/kg penalty for space mining. That means you need some scarce element that costs more than $10k/kg on Earth. What elements cost more than that on Earth? Not a lot.

We would need first to find these elements in deposits so concentrated that the mining plus shipping would cost less than directly mining from the Earth. So far, we haven’t found such highly concentrated deposits anywhere.

I was wrong! We have! The 3rd one on that list.

Turns out the Moon has plenty of Helium-3! According to this paper, there is 10,000x more He-3 on the Moon than on Earth! A total of ~700,000 tons, vs the Earth’s ~30 tons. What? How come?

Our Sun shines because it fuses hydrogen into helium. Some of that helium is the more stable He-4, but some is the radioactive He-3. Some of these helium particles are expelled from the Sun in solar winds. The Earth is protected from these winds by its magnetic field and its atmosphere, which is why we have little He-3.

But the Moon has no magnetic field and barely any atmosphere! So apparently helium lands on its surface and is captured by the ground’s regolith. Wow!

So He-3 is scarce on Earth, but what is the demand for it? According to Bluefors, the company who promised to buy so much of it:

As one of the world’s largest consumers of helium-3, Bluefors utilizes it in its cryogenic measurement systems for applications in quantum technology, physics research, and the medical and life sciences industries. These systems provide the extremely low temperatures of under 10 millikelvin (sub -458ºF/-272°C), needed for the atom-stopping cold, essential for the operation and stability of qubits in quantum computers. Recent breakthroughs from companies such as Google, IBM, Intel, Amazon, and Microsoft indicate that widespread commercial adoption of quantum computing is imminent. In the coming years, the demand for helium-3 will rise sharply to power this next phase of quantum industry growth.

Bluefors leads the market with the most extensive installed base worldwide, having delivered over 1,500 dilution refrigerators and more than 15,000 cryocoolers to date.

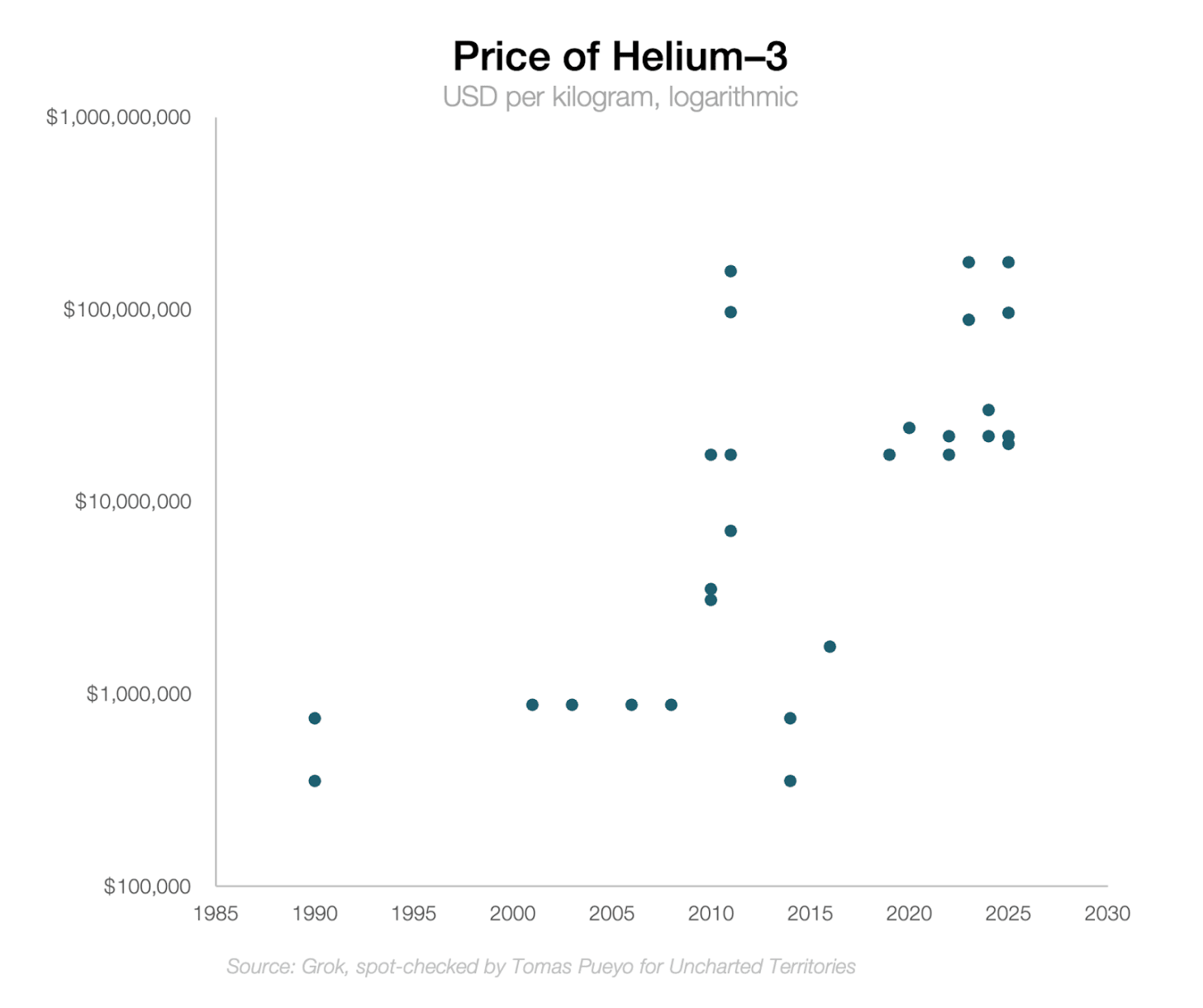

OK so we need radioactive helium to make quantum computers (!!). Wait, it gets better! Helium used to cost something like $1M/kg, but its price has been skyrocketing.

And why is that? Listen to this. Because He-3 used to be a by-product of nuclear arms programs,1 but as nuclear weapon production has dwindled, so has He-3 production on Earth.

That’s why Helium-3 costs about $20M per kg today. Now, if we start bringing a lot of He-3 to Earth, its price would shrink. But Bluefors has committed to spend $300M over 10 years for 10,000 L per year, or 100,000 L in total, which means 11.5 kg, or $26M/kg.2 My guess is they were seeing prices skyrocket, and they decided to secure them for the next 10 years by sourcing the helium from space!

In any case, if your price per kg is $26M, that gives you a lot of leeway to harvest and bring that thing to Earth. How much?

A Falcon 9 mission to Mars would cost ~$67M and could carry ~4 tons. That’s about $17,000/kg, but as of today people pay mostly to send stuff to space, so there is plenty of empty cargo space for the return. Still, let’s be conservative and assume SpaceX would charge $17k/kg. That’s less than 0.1% of the value of He-3! The trip back would not be that expensive.3 What would cost, though, is sending all the machines to the moon to operate this harvest. How much would that be?

Interlune has designed a harvester that can process 100 tons of regolith per hour.

Over 28 days, that’s 33,600 tons4, which backs out to about 0.49 kg per harvester per month.5 Two years of operation would yield about 13 kg, more than the entire cargo that Bluefors has requested for 10 years of operation.

That harvester will weigh about 3 tons.6 ChatGPT tells me you need to add 12 tons of other stuff (processing plant, solar panels, storage, radiators, cryoseparation…), for a total of 15 tons.

15 tons is three Falcon 9 missions, so about $200M.7

If all of this works well, Bluefors will be paying $300M to Interlune so that it can spend $200M of that on sending hardware to the Moon. That leaves $100M to develop all this tech and bring the helium back to Earth. Once that’s done, Interlune would have the entire thing paid for in two years, and it would then have an ongoing harvesting operation on the moon, producing millions per kg of helium.

This is freaking science fiction, but it sounds like it’s happening, and it’s worth summarizing.

We are building quantum computers, for which we need cryogenic cooling that only one element, Helium-3, can provide. Until now, the only place we could harvest it economically was from aging nuclear warheads, and it cost millions per kg. But as nuclear arms have dwindled, the price of that element has skyrocketed to tens of millions per kg, so we’re trying to figure out where to get the damn stuff. It turns out there’s a lot of it on the freakin’ moon. It has accumulated there over millions of years because that’s precisely what the Sun produces when it fuses hydrogen and then sends it flying through space. We don’t catch it because Earth has an electromagnetic shield and an atmospheric shield, which the moon doesn’t have, so the Moon bakes the helium into its soil. We’re now about to send lunar harvesters via reusable rockets so that they can automatically harvest the helium with energy from solar panels, but only two weeks at a time because of lunar cycles.

Fuck. Yeah.

2025-12-06 02:57:32

What was the first metal humans used? You probably won’t guess it.

What did the first metals have in common? It will blow your mind.

What metal promoted the first intercontinental trade?

How did this lead to the first civilizations?

How did its replacement usher in a radically new world?

The stages of human civilization after the Stone Age are the Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age… Why these materials? Why did the Copper Age come first? Why did the Iron Age come later? What came after that? Why did we discover some metals before others? What did each enable? How did the order of metals we discovered influence human history?

These are the questions we’re going to answer today: How metals shaped our early civilization—because they determined the types of tools humans could use, and the civilizations we could build with them.

Ready for the first metal humans discovered and used? Gold!1

Whaaaat!?

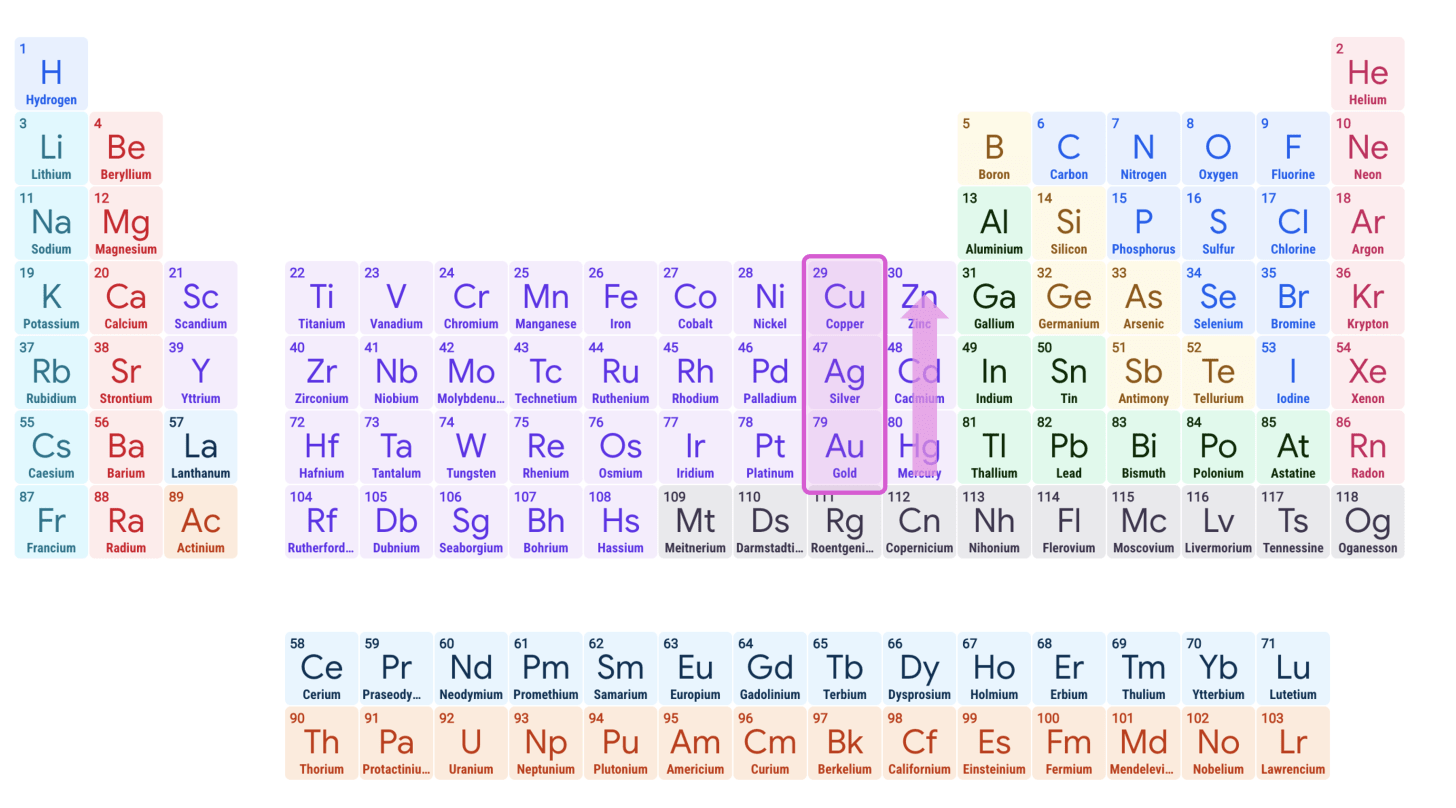

OK here’s another crazy fact: The first three metals that humans discovered were gold, silver, and copper, probably in this order, and here’s how they appear in the Periodic Table.

After your head explodes, you should put it back together and wonder: IS THAT A COINCIDENCE?? I think not. I can hear your brain gears turning: What do they have in common? How did that make them the first metals? How did that determine the history of humans? And then: Oh God, is Tomas going to mix history, geography, physics, geology, and chemistry again? Why yes, yes I am.

But fear not, for I will hold your hand through these scary landscapes and by the end of this article, not only will you better understand the history of humanity, but you’ll also learn some physical and chemical properties of crucial metals for humanity: gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, bronze, iron, and steel.

What the first three have in common—gold, silver, and copper—is that all are native metals: You can find them in their pure form in nature!

How come primitive tribes carried gold as jewelry and not other metals? Here’s a clue:

Here’s another one:

Yes, ancient humans just stumbled upon gold! What a crazy gift from nature! A metal that is valuable because it’s malleable, doesn’t oxidize, is found in nuggets, with a distinctive shiny yellow color to make it easy to find, and a heavy weight to help separate it from rocks in a pan!

How is that possible? you wonder.

In the Earth’s crust, liquid magma separates materials through different temperatures and pressures. Since gold is so stable, it doesn’t mix well with other materials, and when liquid with a high concentration of gold solidifies, gold veins appear.

Once rocks with gold veins are pushed to the surface, erosion carries the other elements away, which are:

Easier to mix with common elements like water, oxygen, silicon…

Lighter, so easier to carry away.

This leaves behind the gold, which is inert and heavy. This is why people find gold nuggets in small mountain streams: Gold doesn’t travel too far, but it can be carried downstream by violent torrents that erode the materials around it. It tends to accumulate in quiet spots in rivers that follow turbulent sections.

So that’s why we had gold first. What about silver?

The first difference between gold and silver is that silver tarnishes.

This made it less common than gold early on, because it bonds very easily with sulfur. To form in its pure metallic form, it needs to be in an environment completely devoid of sulfur, or with agents that take the sulfur out and precipitate the silver back into its pure form.2 These are uncommon, but they exist, and form silver in small wires, sheets, and nuggets.

Given its rarity, early on it was just decorative, until we discovered how to get more of it from ore. We’ll see later when that happened.

So gold and silver were, paradoxically given their actual scarcity, some of the earliest metals to be discovered and used by humans. And what did they do with them at the time?

Gold has always been the perfect store of value, because it’s available, yet very scarce, it’s durable (it doesn’t oxidize), malleable (you can shape it easily, so you can easily mint it into coins, and it’s divisible), portable (valuable enough that it contains lots of value per gram, so you can carry lots of value with you), fungible (two pieces are the same), and it looks beautiful, with its shiny yellow color… The other reason why it was so valuable depended on how many hours of work did it take to produce one kg? The more work it took, the more value a metal could store, and gold was still very rare in native form.

However, gold is too heavy and malleable to be a tool or a weapon, so people had no actual use for it except as a store of value… That’s why gold was used as jewelry and for other decorative items: a perfect way to display your wealth.

Silver is similar, but early on it was much less abundant, and less durable because it oxidizes lightly, so it was much less widespread as a decorative element.

Like gold and silver, copper also exists in native form.

But we said before that native silver was rarer than gold because it binds to other elements more than gold. Well, copper binds to other elements even more than silver.

So we ended up in a situation where, although copper is much more common as an element than silver, and silver more common than gold, their native form is the opposite, so the order of human usage and discovery was the exact opposite!

In other words, gold was the first metal to be known and used precisely because it’s so noble: Since it doesn’t interact with other elements, it accumulated in nuggets that could be easily identified.

Meanwhile, not only is copper rarer than gold or silver in native form, but it’s also much lighter3 and harder than the others, which meant it was more coveted for tools and weapons.

So when we stumbled upon a way to make more copper instead of picking it up from the ground, we paid attention.

Most metals react too much with other elements to remain in native form. They aren’t pure. They might mix with oxygen and form oxides, sulfur to make sulfides, silicon and oxygen to make silicates…

Some of them are pretty nice, like malachite.

So people used these pretty materials among other things as pigments, some of which they used to decorate their pottery.

They already had kilns, big ovens that could reach high temperatures to turn clay into pottery, tiles, and bricks.

When they added these pigments, they might have seen copper form! Copper melts at 1,085ºC, which is higher than fire pits (400-600ºC), but a temperature some prehistoric kilns could reach. Under these temperatures, the carbon from the wood (for fuel) would bond to the oxygen, hydrogen, and other elements in the ore, and extract them. Liquid copper would be released.

Maybe ore like malachite or azurite found itself in kilns as a pigment, or maybe for some other reason, or maybe it was another type of copper ore. In fact, all of the above probably happened in different places at different times. The result was ground-breaking, though: For the first time, humans could make metal.

And this metal was extremely useful, because it’s hard enough to work as a tool like simple hoes or sickles, it could be shaped into pipes and cauldrons, it can have an edge to become a knife, sword, or arrowhead… So the discovery of copper dramatically improved agriculture, cooking, and violence, which led to a population boom and the ability to wage war.

Copper is also reasonably stable (because it’s in the Group 11 we saw before, along with silver and gold), so it could work as money, enabling more trade, wealth accumulation, and the payment of wages necessary to wage war at scale.

In other words, copper made kingdoms possible. That’s why it’s called the Copper Age.

But before we could move into the next age, we needed another couple of metals.

Lead and tin were the next two elements to be discovered.

From Pliny’s writings it appears that the Romans in his time did not realize the distinction between Tin and Lead.—Stannum Tin

Why were these the next metals? How come they were the first non-native metals to be discovered? Because you can make them in a normal fire pit!

Lead is very common in the Earth’s crust, but it’s not a very stable element. It frequently bonds with sulfur to form galena.

Lead melts at 327°C. A wood fire easily reaches 600–800°C. When galena found itself in a fire pit, it became lead!4

My guess is that humans discovered this thousands of times over their history, much before they discovered how to smelt copper. It might have kick-started the technology of smelting.

But lead is not very useful because it’s heavy and way too soft. It couldn’t work as a tool or as a hand-held weapon.

Instead, we used it to cast figurines and amulets, for cosmetics. Later, for early plumbing.

Lead is the heaviest stable element that exists, and this weight was handy for other uses. One was as a weight or a token, super useful for accounting and hence management. The other was as bullets for slings.

However, galena frequently has another metal in it: silver. As we learned to smelt lead, we learned to extract silver. Soon, the value of silver in galena passed the value of lead. This probably had a couple of consequences:

After we discovered the process of cupellation to separate lead from silver, the latter became more widespread. This allowed it to become a currency, and to facilitate international trade.

Because silver justified the smelting of galena, lead became a dirt cheap byproduct that could be used for anything worth using it for. In fact, more than a byproduct, it was a waste product. Because it was so cheap and malleable, it was used for plumbing and cooking vessels in Ancient Rome (and as an additive in wine!), and led to the theory that lead poisoning was one of the causes of the fall of Rome.5

One of the reasons that definitely contributed to the fall of Rome was the exhaustion of silver mines. Like for Chinese empires.

Back to lead. Given its early use, maybe it was the first metal humans worked with heat, and maybe that gave birth to metallurgy, which eventually led us to copper. We don’t know yet. What we do know is that another metal with some similarities to lead was the ticket to the Bronze Age.

Tin is a puny thing. Like lead, tin is malleable, reacts readily with other materials, and has an even lower melting point, at 232ºC. But tin is more brittle than lead, and much less common in the crust (generally in the form of cassiterite), so I assume random discoveries of the metal would have been uncommon, and when they happened, not found very useful. Tin did not lead to the emergence of metallurgy.

But in some copper mines, tin can be found in the same place as copper. Both metals would go into kilns at the same time, forming bronze by accident. And bronze is very useful.

Compared to copper:

Bronze is much stronger and harder. It doesn’t bend or deform as easily, enabling better weapons and armor. While copper axes dulled immediately and blades bent instead of cutting, bronze weapons endured in battle, providing an incontestable advantage to those who weaponized it. Tools lasted much longer, increasing food production.

Bronze melts at lower temperatures, 950-1000ºC instead of 1085ºC, and is very fluid, making it very easy to work. Mass standardization by pouring it into molds became possible.

Oxidized bronze is stable and protects the metal underneath. Copper oxide is flaky. That means bronze weapons and tools lasted longer.

Bronze springs back, while copper doesn’t and fatigues early. Bronze is useful for gears and springs, enabling mechanisms, while copper was worthless for that. Hinges, nails, clamps, joinery elements, valves, fittings for boats and wagons… all became possible with bronze.

In agriculture, bronze allowed us to cut trees for farmland, break heavy soils with stronger plows than wooden ones, use tools for much longer, and create irrigation systems.

Militarily, bronze enabled long, sharp swords, spears able to pierce shields, durable armor, standardized weaponry for entire armies, and so professional warrior classes, territorial expansion, centralization of force… The birth of empires.

In urbanism, it enabled large architecture, as bronze tools were able to cut stone and wood in a way that copper couldn’t. Palaces, temples, huge stone monuments, and even big buildings were impossible before the Bronze Age.

Transportation was also much easier, because without tools to work stone, you couldn’t have stone roads. Copper also doesn’t produce durable axles, properly drilled wheel hubs, rim bands for wooden wheels, pins, clamps, and rivets that hold under impact… All key technologies for wheeled carts. So no roads and no wheeled carts without bronze.

And we know how crucial transportation technologies were to the formation of empires.

This is an even better example: Without bronze, you don’t have seafaring ships. Stone and copper tools can’t cut cedar or oak into planks, so the size of ships was limited to the diameter of trees. But bronze tools could, so suddenly ships became much bigger. This is when civilization starts expanding in the Mediterranean. There are no Phoenician, Greek, or Roman civilizations without bronze.

These ships also allowed water transportation, which was the only way to transport heavy goods like wood, copper… or tin.

And tin had to be transported from afar, because it’s quite scarce.

Since bronze became vital for development and survival in war, tin became survival. So trade became survival. The scarcity of tin drove trade.

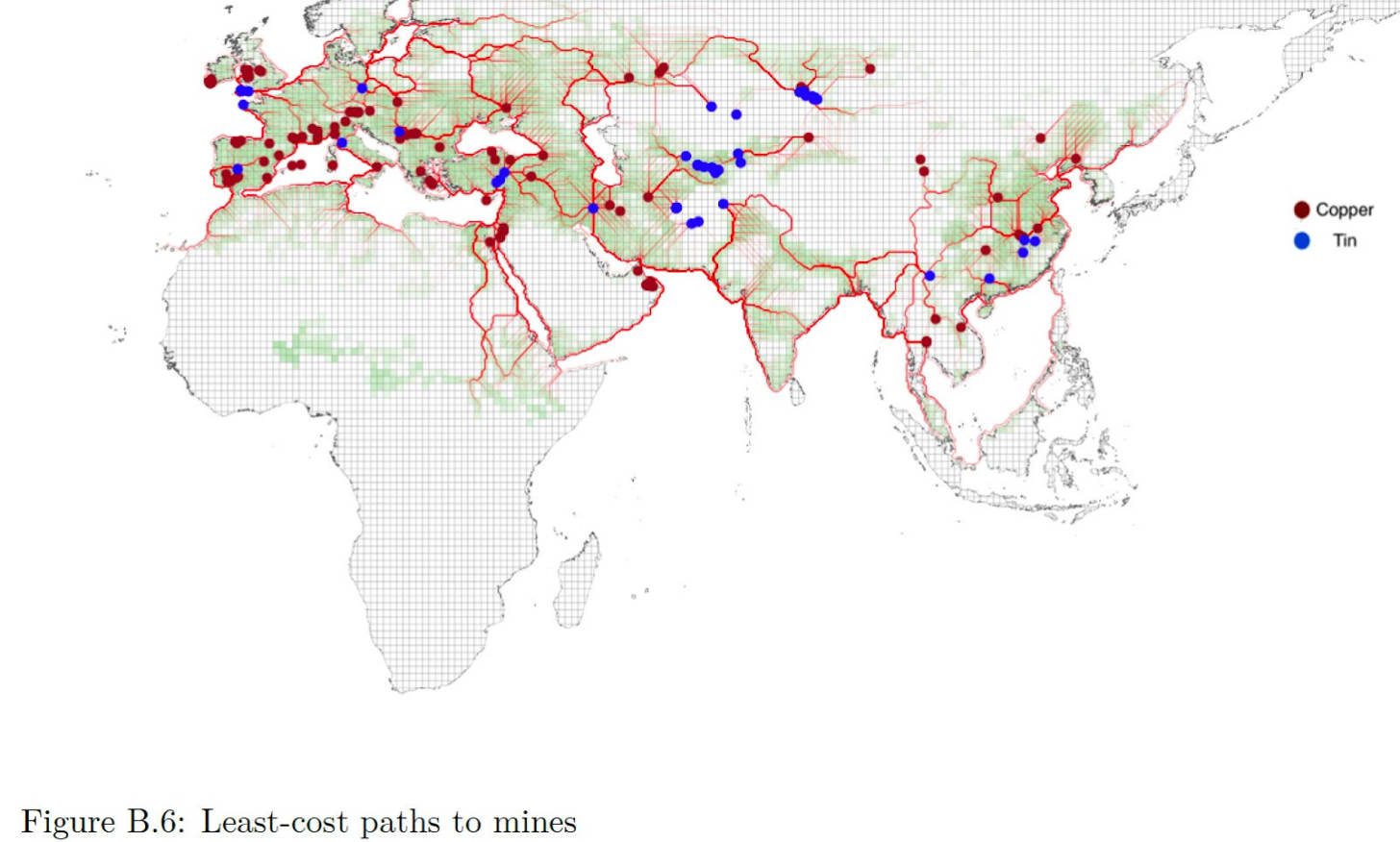

And with it… cities and kingdoms. OK hear me out, because this is nuts: This paper from 2024 argues that the first civilizations emerged not where farming was most productive, but… Where trade between farms and mines could be controlled!

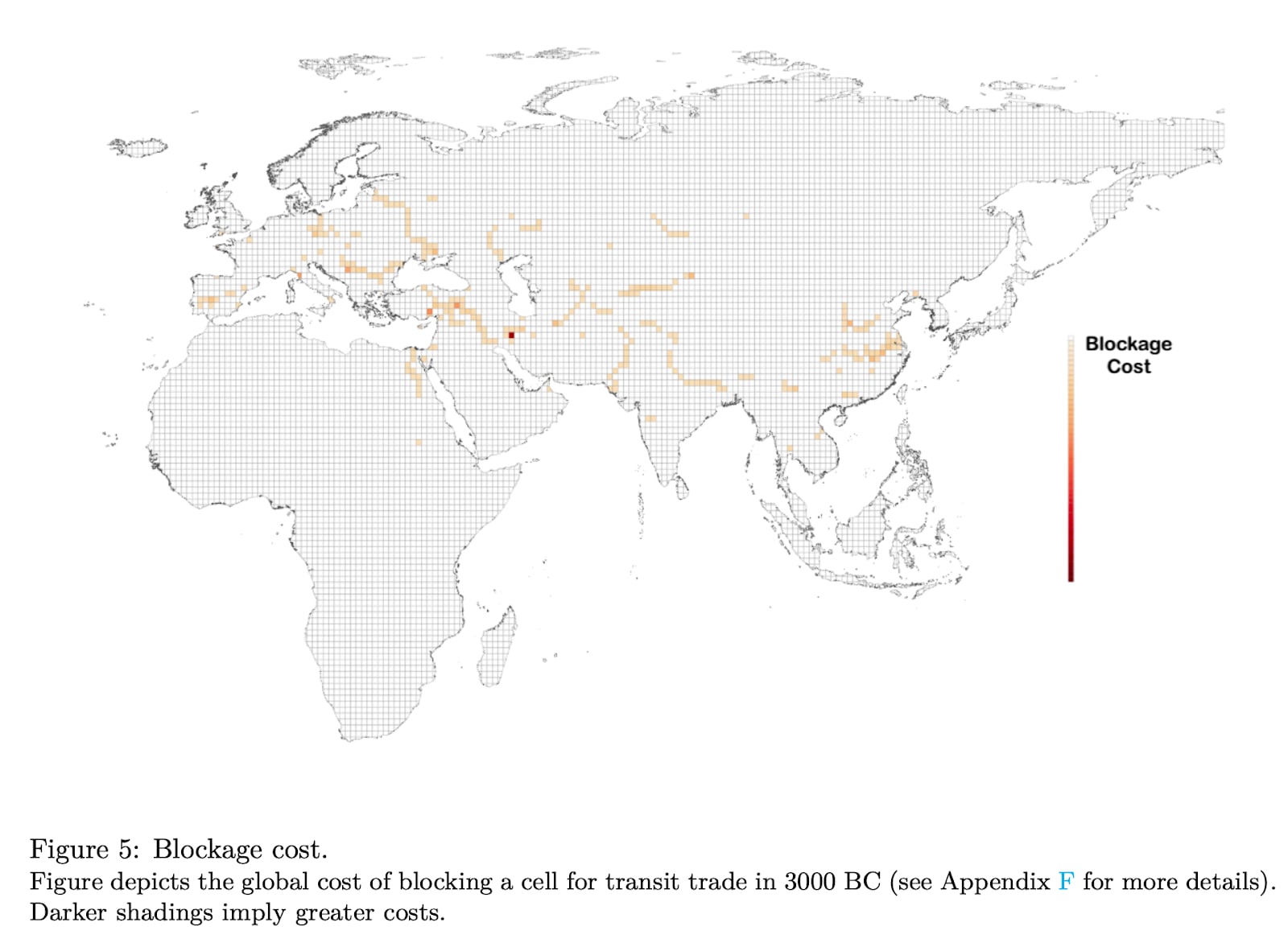

The scientists looked at where the most fertile land was, for agriculture. They looked at where the mines of copper and tin were. Then, the cheapest paths from one to the other. Finally, which of these paths had the fewest alternatives. The idea was: Farmers need tin and copper for bronze tools (and weapons). They will buy these minerals from the mines, so the paths between them become juicy places to make money. If people on those roads tried to abuse their power by robbing or taxing too much, trade would just move elsewhere… Unless it simply couldn’t. These spots were the most likely to have strong cities and states. And that’s indeed what they found!

So although lead and tin are not great metals per se, their early discovery thanks to their low melting point ushered us into a golden age of civilization, maybe by showing us how to smelt ore, by providing the silver we needed to power our economies, and by allowing bronze, which allowed us to get beautiful architecture, better agriculture, stronger armies, faster transportation, international trade, and the emergence of cities, kingdoms, and empires.

The next and final step in this evolution was propelled by iron.

During the Bronze Age, very little iron was used because we didn’t know how to make it. So the only iron we had came from meteorites, like in Tutankhamun’s dagger.

Why wasn’t iron used early? Mainly because its melting point is much higher than copper, at 1,538ºC vs 1,084ºC. Copper could be smelted with much earlier kilns.

But between 1,500 and 1,200 BC, the Hittites in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) started building bigger furnaces that reached higher temperatures. Metallurgists likely discovered it accidentally while smelting copper, using iron-rich rocks to help the copper melt. Eventually, they realized the “waste” material left behind could be forged into a new metal. Soon after, iron spread widely.

But why did it spread? Iron is harder to smelt, you also can’t work iron cold, and it’s actually softer than bronze! What’s the point, then?

A tip comes from when iron became widespread.

You see that transition from Bronze to Iron Age? You know what happened at that time, 1200 BC?

During the Bronze Age Collapse, around 1,200 BC (about when the Trojan War took place), dozens of cities were burnt, destroyed, or abandoned; sea invasions took place, maybe caused by droughts or volcanic winters.

The cause and effect are not clear, but the key to untangle this mystery is that iron is everywhere. Virtually all places on Earth have some iron ore nearby. This has radical consequences:

No need for long-distance tin trades. So if barbarians broke these trade lines, people could fall back on iron.

Conversely, anybody could now build iron weapons, so maybe it’s this wide availability that triggered the invasions of the Bronze Age Collapse.

This combines with another killer feature: With the right amount of carbon and metallurgic treatment, iron can become steel, which is stronger and lighter than iron and bronze and doesn’t oxidize as much!