2025-12-23 15:54:09

In an era where investigative journalism serves as a key instrument for societal change, editing watchdog reporting can be pivotal in making or breaking a story’s impact. From narrowing complex stories to ensuring accuracy, great editing turns strong reporting into powerful journalism.

At the 21st edition of the African Investigative Journalism Conference (AIJC) in November, in this session moderated by Eric Mugendi, managing editor at Africa Uncensored, three leading investigative editors shared how journalists and editors can work together to refine stories that not only expose wrongdoing but also drive change.

Editors can play a key role, even in the pitching stage — by challenging vague story angles, questioning unclear targets, and insisting on concrete source material. A dialogue in the early stages can help turn a general topic into a precise investigative plan that can withstand scrutiny.

Daneel Knoetze, an investigative editor, founder, and director of the accountability journalism project Viewfinder, noted that one of the most common problems at the pitching stage is that reporters offer expansive background and context but fail to identify the specific allegation they want to prove or the target they intend to investigate. Many pitches, he explained, are rich in description but lack the source material required to substantiate wrongdoing.

According to him, editors should encourage journalists to frame each pitch as a hypothesis similar to a criminal investigation: with a potential crime, a suspect, and evidence that already exists or can realistically be gathered. The clearer the hypothesis, the easier it becomes to test and refine.

“Do not bring speculative ideas like who might be benefiting from illegal mining,” he says. “Bring the closest nugget of evidence you have seen, the smallest but clearest piece that can be developed. Editors must help reporters take a broad idea and tighten it into a specific, recognisable hypothesis with sourcing already in hand.”

Knoetze noted that essential source material is often buried deep in the pitch or entirely absent. For editors, the task is to interrogate the evidence available and determine whether there is enough minimum substantiation to justify moving forward. Only when that baseline is met should a newsroom commit time and resources to a longer-term investigation.

Once a pitch is approved, the true investigative work begins, but according to Knoetze, this is also the point where many reporters lose focus. He says investigative journalists often drift into side research, academic-style reading, and other tangents that contribute nothing to the core allegation. He often urges reporters to step away from academic-style backgrounding and instead deepen their strongest real-world access.

“People think they’ve got all the time in the world,” he says. “They do a lot of sidetrack research and secondary reading. They don’t recognise the value of primary sources that get you closer to real insights and something genuinely expository.”

To prevent reporters from getting lost in the volume of information they collect, Knoetze said editors should frequently check in and guide them back to the essentials. What is the specific allegation? What finding is being pursued? What does the minimum story look like today, based on the evidence in hand?

He advises reporters to imagine the story going on the front page this weekend. How would it read with the material they currently have? And if the team had an additional few weeks of reporting time, what could the maximum version of the story become, and what source material could realistically be accessed within that timeframe?

An editor’s role can also be key in challenging blind spots and helping reporters see the bigger picture. This involves asking tough questions, verifying facts, and encouraging critical thinking about balance and fairness. The aim is to make the story more complete, accurate, and impactful.

Ida Jooste, a South Africa-based health and science journalist who has led newsrooms in Durban, Johannesburg, and Nairobi, says that she always advises journalists to approach their stories as though no one believes them. She tells them to imagine that only their mother, grandmother, and best friend believe what they have uncovered is true.

The editor’s role, she said, is to help journalists gather sufficient evidence, and the best way to do that is to work as if the story must convince even the most skeptical audience.

By the time journalists reach the writing stage, they are often so immersed in their material that they lose sight of what truly matters. Knoetze, director of Viewfinder, stated that this closeness frequently leads reporters to bury the lead simply because they have lived with the story for so long. “Journalists are very close to it, they’re in the bubble,” he says, noting that they can become so attached to the various pieces they’ve gathered that “they don’t really see the wood from the trees.”

Knoetze explained that one of the editor’s most important responsibilities at this stage is to identify and elevate the most consequential elements of the reporting. This includes foregrounding the strongest sourcing, the most original discoveries, and the most damning findings so they become impossible for the reader to miss.

Hamadou Tidiane Sy, founding editor-in-chief of Ouestaf News and a leading investigative journalist in Francophone Africa, recalled an investigation he co-produced over two-and-a-half years. His initial draft was 4,500 words. Editors recommended cutting it by more than half, a decision he initially resisted. In hindsight, he said, the shorter 2,000-word version was far more accessible and concentrated the investigative quality, making it stronger. “Every sentence and phrase has to pack a punch,” he noted. “If it doesn’t, you’re probably better off tightening and cutting for impact.”

Keeping the audience in mind is essential, Knoetze added. Readers arrive with no context, no prior knowledge, and no emotional investment in how the story was gathered. Editors must therefore ensure the narrative is structured with clarity and intention, guiding the audience from paragraph to paragraph in a way that is accessible and engaging.

He added that effective structure requires purposeful framing. Stories should make their objective clear from the outset and be shaped toward accountability, whether that means prompting regulators to act, enabling prosecutors to take up a case, or equipping civil society with evidence that strengthens advocacy efforts.

Now in the editing chair, Sy has spent years guiding reporters, shaping stories, and navigating the balance between accuracy and narrative. From his work at CENOZO, a network of investigative journalists across West Africa, to his own newsroom, Sy has seen the intricacies of editing up close and has judged numerous journalism awards.

“Most of the time, the first story a reporter writes is one they are very proud of,” explains Sy, who hails from Senegal. “Submitting it to an editor is a moment of accomplishment. The journalist believes they have done everything they could. Yet the story often returns, marked with questions, corrections, and requests for revisions.”

The process, he notes, can be relentless, but it’s a vital part of the editorial process.

“The minute you are told you are the editor of the story, there’s a responsibility,” Sy said. “If the story has flaws, if it is unclear, if it is misleading, I am responsible.”

He noted that award-winning stories are often the product of this invisible labor. Editors shape the narrative, refine the prose, and ensure the integrity of the reporting, even when recognition goes elsewhere. In this way, he explains, editing is both a craft and a commitment.

“The most difficult parts are the narration and the style,” he added. “If you are an editor, you look at all of those things. It’s not just reading and correcting a couple of typos.”

Daneel Knoetze, standing, an investigative editor, founder, and director of the accountability journalism project Viewfinder, in a session at the AIJC. Image: Leon Sadiki for AIJC

Knoetze stressed the importance of the final line-by-line edit and fact check. Investigative reporting carries consequences, and assumptions cannot be left unchallenged. Every sentence must be substantiated, especially when the story may trigger strong reactions or legal repercussions. This final stage ensures the story is strong enough to withstand skepticism, pushback, and public scrutiny.

By thinking as if no one believes the story, working as if external doubt must be overcome, and editing as if any assumption could be wrong, reporters and editors can strengthen the investigation, uphold fairness, and produce work that stands up to make an impact.

Since investigative journalism requires more time, attention, and closer editing than other kinds of reporting, resources can be a constant challenge. Small newsrooms often struggle to provide sufficient editing support for every story. This can delay publication because the editorial process itself needs to be as thorough as possible.

“Either you spend a lot of time and energy on each story, which means fewer stories overall, or you hire more people, but where do you get the money from?” said Sy.

One way around this resource squeeze in recent years has been collaborative investigative journalism, where different newsrooms work together, but this presents its own editing challenges. Different news organizations bring varying standards of rigor and style, which can complicate the publishing process. Sy recalled reviewing a story already approved by a partner editor and finding it unpublishable. Reconciling these differences, he explained, requires careful judgment, negotiation, and the courage to prioritize quality over convenience.

“Uneven standards, particularly in collaborative projects, are challenging. You have one team with their standards, another team with theirs,” he said. “How do you reconcile the two to produce a strong, publishable story?”

For Sy, a story’s true test of its quality is whether it keeps the reader engaged from beginning to end. When evaluating journalism for awards, he said he asks colleagues whether they would have read a story to the end if they were not judging it. Many stories, though factually correct and technically sound, fail because they do not engage the reader. Investigative journalism, he emphasized, must be both accurate and compelling. Data, facts, and evidence are essential, but storytelling gives the story life and reach.

Editing with this storytelling in mind, he acknowledged, is both an art and a science. It demands patience, insight, and constant attention to the audience. It is about shaping a narrative that is truthful and human, precise and readable, immediate and enduring.

“If I found a story in a newspaper, I would read the first two paragraphs, and then decide whether to continue,” he noted. “Investigative journalism is about facts, and at times those facts can be dry. But how can we make it compelling? How do we make it a story everyone wants to read? The numbers are there, the facts are there, the data is there; it is accurate, it is brilliant. But if it’s not a good read, nobody is going to finish it.”

Abdulrasheed Hammad is a Nigeria-based lawyer and award-winning freelance journalist who reports on science, climate change, accountability, health, education, and data-driven governance. His work has appeared in The Cable, HumAngle, Minority Africa, El País, The Continent, and Dataphyte. He is a recipient of the Africa Science Journalism Award, won best investigative journalist in the 2025 Diamond Awards for Media Excellence, and was a finalist for the 2025 Thomson Foundation Young Journalist Award.

Abdulrasheed Hammad is a Nigeria-based lawyer and award-winning freelance journalist who reports on science, climate change, accountability, health, education, and data-driven governance. His work has appeared in The Cable, HumAngle, Minority Africa, El País, The Continent, and Dataphyte. He is a recipient of the Africa Science Journalism Award, won best investigative journalist in the 2025 Diamond Awards for Media Excellence, and was a finalist for the 2025 Thomson Foundation Young Journalist Award.

2025-12-22 16:00:39

Many of GIJN’s most memorable original stories in 2025 reported on new thinking and innovative strategies to tackle emerging journalistic challenges in an era of dwindling resources and rising threats for independent media.

Numerous pieces dealt with sustainability strategies flowing from the dismantling of USAID and other funding headwinds, and GIJN’s pages featured many more stories on new opportunities and challenges facing Asian newsrooms, in the run-up to the first-ever Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25) held in Asia, which recently concluded in Malaysia. The need for solidarity, innovation, and radical collaboration among investigative teams was a frequent theme, and powerfully underlined by Nobel laureate Maria Ressa at the GIJC25 keynote session.

In the curated list below, we highlight a diverse set of eight stories from GIJN contributors in 2025: a mix of our most popular stories, inspiring reads, game-changing tipsheets, and features that reveal new tools triggered from smart thinking.

Image: Shutterstock

For potential whistleblowers, there is more to worry about than the legal and security risks of sharing privileged information. Experts and whistleblowers themselves say they also worry about the broader stakes of coming forward: the degree to which their lives might change.

One important GIJN story this year revealed a new effort among civil society organizations to broaden disclosure to journalists — and deepen whistleblower protection — by reducing those stakes with tools and help that address the many reasons leakers might hesitate. The piece included revelations by key sources, including former Uber whistleblower Mark MacGann, that systems are urgently required to offer true anonymity to public interest leakers and to address the “first mover” problem, in which people are generally fearful of becoming the only employee to share information.

The piece highlighted a highly innovative service from a nonprofit called Psst.org, which offers a secure digital safe for even small disclosures, flexible or immediate pro bono legal support, and — in an innovative twist — can match a potential whistleblower with others who have similar concerns.

Established in late 2024, the service is designed to address the various worries, threats, and security risks facing potential leakers in government departments and the tech industry. As the website states: “Psst lets you deposit the information and get help without having to go full ‘whistleblower.’” GIJN’s reporting reveals that Psst has already received roughly 100 whistleblower support requests in its first year, including submissions by 55 concerned employees to a beta version of its encrypted safe.

Image: Nyuk for GIJN

In a highlight of GIJN’s regular 10 Questions series that focuses on leading investigative reporters and editors, this piece by GIJN Chinese editor Joey Qi unearthed key sustainability insights from a pioneering Taiwanese journalist, Sherry Lee Hsueh-li.

Now the deputy CEO of The Reporter — Taiwan’s first nonprofit media outlet established by a public foundation — Lee offered practical and inspirational insights on both kinds of sustainability: a successful business model for public interest journalism, and ways for stressed investigative journalists to avoid burnout and keep digging. Remarkably, both involve reader input.

Concerned about dwindling resources for in-depth investigations — and inspired by nonprofit newsrooms such as ProPublica, Germany’s Correctiv, and South Korea’s Newstapa — she reveals how her team at The Reporter earned reader support through consistent story impact, transparency, and no paywalls.

Lee also revealed the value of a deep focus on a single topic, in describing The Reporter’s cross-border collaboration with Indonesia’s Tempo, Slaves of the Far-Sea Fishing, which exposed human trafficking and labor exploitation in the region, and triggered policy changes. In addition to warnings about the context limits of AI use, she shared helpful open source tools for resource-challenged newsrooms and a key warning that even the consent of an anonymous source to your protection plan is often not enough.

Of the future, Lee said: “I also hope for a deeper public understanding of the sheer difficulty and value of investigative journalism.”

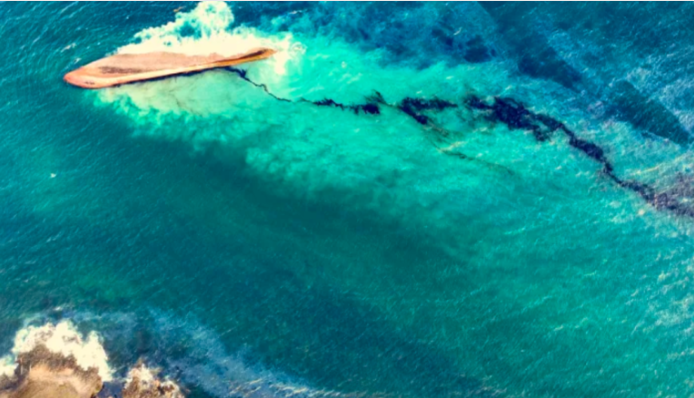

Bellingcat used the special knowledge of a marine hobbyist to unlock the identity of this capsized vessel — a towed barge — and hold its owners accountable for the vast oil spill it caused in the Caribbean. Image: Screenshot, Office of the Chief Secretary of Tobago

As investigative tipsheets go, this story was surely a first. That’s because amateur transportation hobbyists are rarely taken seriously by people outside of their areas of enthusiasm, and the data they curate is almost never grouped with traditional data sources. However, as this piece revealed, some expert investigators insist that “planespotters,” retired engineers passionate about their hardware, and other enthusiasts represent a largely untapped source of data and media-friendly leads and information.

In eye-opening insights shared at the NICAR25 data journalism summit, researchers from the investigative nonprofit group Bellingcat revealed how data from amateur enthusiast sites and chatrooms had unlocked several otherwise “stuck” investigations involving the ownership and movement of ships and aircraft. For instance, information from two sites — ShipSpotting.com and tugboatinformation.com — was key to identifying a capsized barge that created a vast oil spill in the Caribbean, as well as the tug that abandoned it.

The piece included practical tips for finding hobbyist sites, such as using search terms like “log a sighting,” and an example list of reliable sites.

Bellingcat researcher Logan Williams also revealed yet another little-known benefit of reading hobbyist forums: discovering the precise jargon to use in onward technical search. For instance, the story detailed how the team’s discovery of two terms — “WS3” for “weapons storage and security system,” and “PAS” for aircraft shelters — helped Bellingcat expose alarming nuclear weapons security breaches in Europe.

Image: Shutterstock

In one of the most popular GIJN tips stories of the year, Turkish editor Pinar Dag produced a strong introductory tipsheet on how reporters without coding skills can clean up the messy datasets that governments often share.

As the piece noted: “Today, around 80% of digital data is unstructured, posing a significant challenge for journalists: before conducting meaningful analyses or uncovering stories, the data must first be cleaned and organized.”

The story also featured clear steps for data cleaning; easy-to-use tools; ethical considerations; and simple formulas to organize unstructured information in spreadsheets. Audiences learned easy ways to delete duplicate spreadsheet rows; convert all dates to a standard format; merge duplicate records; and visually organize data.

Dag concluded: “Think of yourself as a storyteller, not an engineer — but remember: every strong story depends on solid data. With the right tools and methods, even non-coders can clean data and turn it into reliable news.”

Image: GIJN

Stories on the finalists chosen for the Global Shining Light Award (GSLA) tend to make annual GIJN’s Top Stories lists, simply because of the practical inspiration the highlighted investigations offer for the global community. And this year was a prime example.

Divided into categories for large and small/medium outlets, this prize honors watchdog journalism in developing or transitioning countries carried out under threat, or in perilous conditions, and the 2025 edition attracted 410 entries from 97 countries.

This round–up of the shortlist described seven powerful exposés in the large category, including stories on pressing topics such as immigration, organized crime, and human rights violations in war zones. It highlighted a blockbuster investigation by Mongabay, which uncovered links between a network of drug trafficking airstrips in the Peruvian Amazon to a campaign of violence and assassinations against Indigenous leaders and communities. Another summary focused on a collaborative project co-led by El CLIP, which revealed a hidden, lethal safety threat to migrants being trafficked within Mexico. It also described the courage and ingenuity of reporters working on hyper-difficult topics in Gaza, Ukraine, Nigeria, and Turkey.

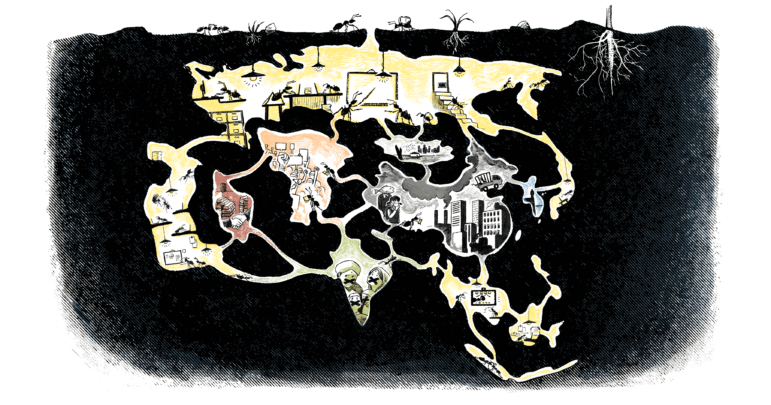

Illustration: Nyuk for GIJN

Serving as the anchor piece for a major, two-week “Asia Focus” story series, this story by Pınar Dağ and GIJN’s Asia editors set out both the growing challenges and collaborative opportunities facing that continent’s independent media community.

“While journalism in Asia is currently besieged by authoritarian state structures, censorship, and digital misinformation threats, it is also being redefined by younger generations armed with new media tools, and remains an invaluable method for holding power to account,” it pointed out.

The fundamental obstacle facing Asian journalists is chillingly displayed in one embedded graphic, showing a dramatic decline in press freedom in the past decade. But it also reveals growing public support for investigative journalism in places such as Indonesia, Thailand, and — especially — the Philippines, where independent newsrooms continue to inspire with innovative models for investigation and public engagement.

It also summarized the results of a survey of GIJN’s more than 30 Asian member organizations, and included regional deep dives on issues facing Central Asia; India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka; Southeast Asia; and China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Image: GIJN, Sigma Awards

Recognizing the Sigma Awards’ new home at the Global Investigative Journalism Network, this piece dug into the impact and future of the premier prize recognizing the best data journalism around the world.

The richly-sourced story explained how the 2,875 project entries from more than 100 countries in the competition’s first five years have served as a catalyst for more ambitious and innovative public interest projects for newsrooms of all sizes in every region, and also as a map for the evolution of data journalism itself.

As former Sigma executive director Marianne Bouchart explains: “The Sigmas aren’t just about who’s best — they’re about what’s possible.”

Topics tackled by shortlisted entrants over the five years represent a showcase of the world’s most pressing challenges, from COVID-19 response failures and hidden climate change impacts to rising authoritarianism and the growth of cross-border organized crime networks. Asked for favorite entries that blazed new trails on what is possible, jury members cited the Financial Times’ How China is Tearing Down Islam — which used free satellite imagery to show that three quarters of the 2,312 mosques analyzed in China had been physically modified to erase Islamic features — and Mapping Makoko, in which the group Code for Africa used drones, document analysis, and an active partnership with residents to literally put a neglected Nigerian informal settlement on the map.

Gina Chua, chair of the Sigma Prize Committee, also reveals two key innovations that led to a dramatic growth of entries from the Global South: the expansion of the application form to eight languages, and the elimination of all prize categories. This expansion is well illustrated via an interactive graphic within the story. (Applications for the 2026 awards are now open.)

In a map that reveals the global reach of free satellite data, the areas in green (above) are those imaged by the medium to high-resolution Sentinel 2 satellite constellation every five to six days. Image: European Space Agency

A richly useful and popular GIJN webinar on free satellite image access this year led to a blockbuster panel at the NICAR data journalism summit in the US, and also to this broader story on the game changing availability of this technology for investigative teams. The webinar itself was triggered by the popularity of an earlier GIJN feature sharing the insights of the ultimate sources on the access topic: journalists who were formerly engineers with private satellite companies. This series of GIJN training resources reflects both a vast appetite for free remote sensing evidence among journalists around the world, and the new availability of images from space at ever-higher resolution.

While a misperception persists among many newsrooms that satellite imagery either involves high cost or special media arrangements with private companies, Carl Churchill, graphics reporter at The Wall Street Journal, noted: “Most satellite data is free, open, and global.”

The 2025 story highlights the powerful, easy-to-use features of the open source Copernicus Browser, which allows single image downloads, a simple cloud cover filter, data overlays, and compelling timelapse displays. The story also revealed new use-cases for these images, such as scouting perilous field reporting trips prior to travel. And it quotes a former satellite company engineer — data journalism trainer Laura Kurtzberg — on numerous tips to pitch commercial providers for the use of ultra-high resolution imagery in investigations.

Image: Shutterstock

This emergency response story in February set out the sudden crisis for independent nonprofit media from the shock freeze on USAID foreign assistance funding, as well as mitigation strategies and inspirational solidarity from the investigative community.

In response to the sudden loss of US$268 million in agreed grants for independent media in more than 30 countries, key sources shared urgent tips on legal challenges, reader support models, and funding diversification strategies. But the story also showed the devastating harm to public interest journalism caused by the Trump administration’s decision, including grave threats for exiled outlets and independent media in places such as Ukraine, Cameroon, and throughout Central America. The piece shows how Ukraine’s Slidstvo.info, an award-winning independent investigative agency, lost 80% of its funding in a single day in January, and how the independent Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) was forced to lose the services of 43 valued reporters and staff, after losing 29% of its total funding.

Imagen: Shutterstock

In future-oriented reflection on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day, this piece unpacks the dual threats to independent journalism from rising authoritarianism and the rampant advance of AI.

It also illustrates the alarming landscape journalists already faced in 2025, including a Reporters Without Borders finding that the global state of press freedom had reached an unprecedented low point — with the worldwide press freedom situation ranked as “difficult” in the World Press Freedom Index, and “poor” for half of all countries.

While noting some important new opportunities and use-cases for investigative reporting presented by new tools — including some generative AI platforms — sources cited in the story explain how this technology can pose a threat to the sustainability of newsrooms, to accountability in the public interest, to minority rights, and to democracy itself. Indeed, it reveals that investigative journalism, in particular, serves as “as an antidote to the scourge of AI manipulation and misinformation” — and profiles a series of powerful investigative projects around the world that have already exposed both intentional and unintentional harms flowing from these algorithmic systems.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

2025-12-19 16:00:52

News coverage in 2025 was dominated by several seismic events, with data journalism outlets closely tracking a world shaped by US trade hegemony, the rising influence of AI, and the persistence of conflicts. US President Donald Trump’s second term ushered in sweeping global tariffs and deep spending cuts, and sowed uncertainty across the global economy.

Meanwhile, the rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence and data centers was a focal point worldwide, highlighting the growing impact of technology on economies and society. Conflict and war remained central to the year’s reporting, with many of the stories featured in our list this year focusing on the Russia-Ukraine war and the war in Gaza. Other key topics included the election of a new pope, the spread of wildfires, and issues surrounding social media usage and misinformation.

In 2025, we published 22 editions of GIJN’s Data Journalism Top 10 column, covering well over 200 stories. For this end-of-year round-up, we bring you a selection of global highlights following a criteria that has grouped stories by prominent news topics, and assessed stories for the rigor of their methodology and the quality of execution, while considering the depth and creativity of the reporting.

Conflict accounted for roughly 14% of the stories in our columns. Reports on the Russia-Ukraine war, Gaza, and Sudan produced some of the year’s most in-depth investigations, combining open source intelligence, mapping, social media analyses, and on-the-ground reporting to convey the human costs of war.

Image: Screenshot, Texty

The war in Ukraine was defined by incremental Russian advances, expanded drone and long-range attacks, and intense ceasefire efforts that ultimately failed. At least 19 articles we featured this year focused on some aspect of the war, but assessments of how the proliferation of AI is shaping the conflict online provided a particularly compelling angle. Ukrainian outlet Texty examined how large language models (LLMs) from the US, France, China, and Canada interpreted the war, asking thousands of English-language questions across thematic areas including geopolitics, history, and national identity. Responses ranged from pro-Ukrainian to pro-Russian, revealing significant biases in AI models: Canadian LLMs ranked most Ukraine-friendly, while Chinese models showed the strongest pro-Russian bias.

Despite a fragile ceasefire being brokered in October, the war in Gaza has claimed the lives of more than 70,000 people and left more than 170,000 injured. After a cessation of hostilities in spring, fighting in Gaza resumed with repeated Israeli offensives and the blockade of essential aid, which led to one of the most alarming aspects of the war — famine. Building on prior analyses of Israeli attacks on aid in Gaza, a detailed investigation by Forensic Architecture and the World Peace Foundation found that starvation had become a deliberate tactic employed by Israeli forces. Researchers documented attacks on civilians collecting aid and the destruction of critical food infrastructure, using open source data and spatial analysis. Each incident from March 18 to August 1, 2025, was geolocated, timed, and verified with video and satellite imagery, revealing a systematic pattern of intentional targeting of Israel-run aid sites.

El Mundo also released a special report which similarly highlighted the dire humanitarian crisis, following a father’s struggle to access food, with illustrations and maps revealing deadly delays at aid distribution centers.

Sudan’s civil war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) escalated into a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, with mass killings, the 18-month siege of El-Fasher, famine, ethnic violence, and reported “killing fields” that rights groups warn may amount to genocide and war crimes. A joint investigation by Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) and Al Mohajer revealed how smugglers and criminal gangs preyed on refugees fleeing the violence. Focusing their investigation on refugees crossing into neighboring Egypt, reporters interviewed a dozen survivors of smuggler-related violence and surveyed 324 refugees, and found that a number of men and women had been raped or sexually harassed. Through interviews, the journalists mapped four main smuggling routes in an interactive visualization showing border stops approaching a quarry region near Aswan, a city in southern Egypt. Similarly, a collaborative investigation by Sky News, Sudan War Monitor, and Lighthouse Reports used open source reporting to expose how paramilitaries hunted down civilians who fled El-Fasher and killed them in surrounding “killing fields.”

After Bashar al-Assad fled Syria in December 2024, many thousands of exiles — including journalists — were able to return to the country for the first time in decades. Over the following year, local and international journalists embarked on the challenging work of collecting evidence for potential war crimes, finding the disappeared — and investigating Syria’s notorious prisons, where the regime had held and tortured tens of thousands of dissidents. With detailed footage, images, and documents, The New York Times produced a 3D model of Sednaya prison on the outskirts of Damascus, providing an interactive look at the interior, a detailed guide to each part of the building and its purpose, and tracing the individual stories of several prisoners held there.

Extreme weather and natural disasters in 2025 marked another year of widespread climate change, from Hurricane Melissa making land as the biggest storm to hit Jamaica, to a typhoon in Hong Kong and flooding in Pakistan and India after record-high rains in late April.

Several outlets focused on the devastating impact of wildfires in Europe and the US. In particular, California wildfires featured in several investigations, looking into everything from the structures of homes that survived fires to the failed preventative measures aimed at stopping the spread. Reporters from High Country News and Type Investigations conducted a first-of-its-kind analysis after a catastrophic wildfire sparked by a damaged transmission tower, which led to state regulators in California introducing new wildfire prevention rules. One of the fixes deployed by PG&E, the state’s largest utility company, saw a change to the fast-trip settings that automatically cut electricity when equipment detects a potential physical hazard that might spark a fire. Using data from Cal Fire and PG&E to map service areas and circuit lines against wildfire locations while tracking cumulative power outages from 2022 to 2025, the findings show that rural communities, which often border forests and face higher fire risk, experienced 600% more fast-trip outages than urban areas.

Elsewhere on this topic, we also recommend the The Washington Post’s visual explainer of why some houses survived the Los Angeles wildfires, which mapped fire damaged properties by location, and explored the age of the properties that were destroyed while assessing photographic evidence of the damage.

In this piece published in early 2025, data outlet InfoAmazonia detailed how more than half of the municipalities in the Brazilian Amazon suffered from drought throughout the previous year. Starting with data analyzed by Brazil’s National Center for Monitoring and Alerting of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), the story found that 59.5% of the municipalities in the region experienced drought in 2024. The InfoAmazonia team also investigated this issue on-the-ground by sailing the Solimões River in the state of Amazonas and visiting riverside communities impacted by drought issues. The report included graphs showing the variation in each month of the year, the situation in the areas worst affected by drought, and data measuring the commitment of politicians to the environment.

AI dominated headlines in 2025, and data journalism teams tracked its impact on employment, the rapid proliferation of data centers, and the expansion of AI into industries from finance to creative sectors — all of which sparked debate on automation, regulation, and the consequences for society.

A number of news organizations looked into the growth of energy-thirsty AI data centers, but Bloomberg’s analysis of what it’s costing Americans conveyed the implications of AI use in a particularly effective way. It tracked wholesale electricity prices to understand the impact on the power grid of AI data center proliferation, comparing prices in 2020 with those in 2025. Bloomberg found that in areas near significant data center activity, wholesale electricity prices rose as much as 267% in a single month. After analyzing 25,000 “grid nodes” they found that more than 70% of those showing price increases were located within 50 miles of data center activity. With data centers forecast to account for 9% of all US power demand by 2035, the reporters said the “unprecedented granularity” of their data showed what is at stake for those living nearby this AI infrastructure. Also compelling was this FT story on data centers that included a visual, interactive look at the inside of a data center, including equipment, layout, processes and ultimately, the energy needed to fuel AI data centers compared to conventional ones.

Africa Uncensored, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network, investigated how companies recruit thousands of AI “tutors” tasked with training artificial intelligence systems by providing corrections to large language model (LLM) responses. At first glance, these mass hirings alluded to vast opportunities, but rather than providing steady work, they served a different purpose — what experts call “labor hedging,” a tactic to impress investors and Big Tech clients by projecting the readiness of a workforce and scalability to land contracts. To test this, journalists tracked jobs posted by micro-tasking platform Mindrift — a subsidiary of former-Russian-owned tech company, Toloka — from March to July, visualizing 5,770 postings across 62 countries and highlighting how the Artificial General Intelligence arms race exploits a largely Global South workforce.

In 2025, the social media landscape was marked by the rise of political extremism and widespread misinformation, with investigations revealing algorithmic biases, coordinated disinformation campaigns, and the manipulation of platforms to influence public opinion.

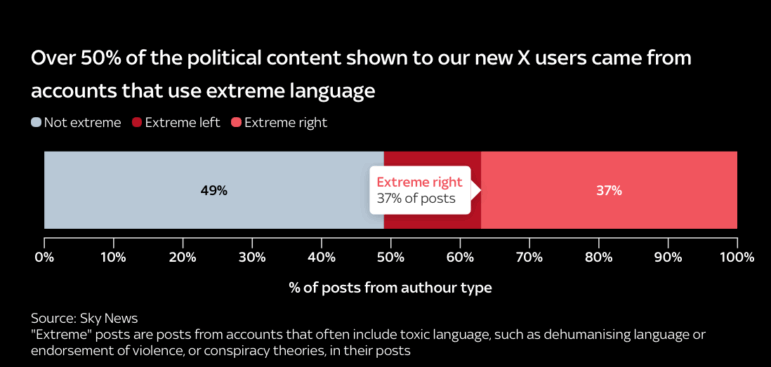

Image: Screenshot, Sky News

Sky News’s data and forensics team set out to test whether X’s algorithm favors right-wing political content by running a controlled experiment using newly created test accounts designed to mimic British users with left-leaning, right-leaning, or neutral interests. Over two weeks, the team collected posts from the “For You” feeds of these newly created accounts, building a dataset of 90,000 posts. Working with academics, they classified the accounts showing up most often in the dataset by political alignment using a custom-trained large language model. Using color-coded, circle-packing charts to illustrate their findings, they showed more than 60% of political content shown to these new users came from right-wing accounts, that neutral users saw twice as much right-wing content as left-wing, and over half of all political posts shown to new users originated from accounts classified as extreme, which they defined as using toxic or dehumanizing language, or which endorsed violence or conspiracy theories.

Another noteworthy investigation was an ARIJ collaboration with Code for Africa on social media posts focusing on a cluster of hashtags spreading disinformation and promoting climate change conspiracy theories. The investigation revealed that hashtags were predominantly pushed by accounts with ties to oil interests in Gulf states and uncovered a coordinated effort to amplify climate conspiracy narratives through networks of automated and semi-automated accounts.

Economic policies under US President Donald Trump, including high tariffs and steep spending cuts, had far-reaching national and global effects in 2025. Trump’s introduction of global tariffs marked the largest overhaul of US trade policy in decades. Several news organizations set up tariff trackers to catalog the flurry of levies placed on everything from film production to cars to steel — the size and frequency of which varied by the week and sometimes but the day. While it was hard to pick the best tracker, we found the Financial Times’ tackling of the topic particularly compelling. Examining the US’s biggest rival, China, whose trade surplus recently surpassed US$1 trillion, the FT highlighted why Trump may have aggressively pursued tariffs, continuing his long-standing strategy of using them to pressure China. Using Chinese customs data, FT reporters presented a series of charts on trade relations between Beijing and other countries, and the products traded that added up to the country’s 2024 trade surplus. The data showed how, for example, China produces almost one-third of all the world’s manufactured goods and how the country is increasing its surplus through strategic trading partners.

On May 8, Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost was elected pope — adopting the name Leo XIV — marking the first time a US-born citizen was chosen as pontiff. Atlo, the data team from Hungarian investigative outlet Átlátszó, produced a detailed illustrated piece, including a guide to the rites involved in the conclave, which had the largest number of voting cardinals in history. It included a series of maps showing the location of papal tombs in Rome and in Europe that still exist today, and a 3D model of some Vatican buildings and the Sistine Chapel, where the conclave has been held since 1878. It also presented graphs on the diverse origins of the electors, the balloting and voting process, and positions of the main papal candidates on key issues.

The Reuters data team produced a series of notable data investigations this year — with highlights including what it’s like to occupy a hot prison cell and a piece exploring migrant journeys in the Mediterranean. But taking the lead for us this year was a special report in which the team used mapping and satellite imagery, alongside scanned documents and email excerpts, to show how Iran has built a multibillion-dollar global oil trade despite a raft of sanctions by the West. The investigation stemmed from a series of leaked emails exposing granular details about the day-to-day workings of an Iranian company. According to the leak analysis, from March 2022 to February 2024, the company helped deliver 18 different sanctioned oil cargoes from Iran to Venezuela, northern Russia, and a series of ports in China via a ghost fleet of 34 vessels. According to the investigation, the total amounted to nearly 20 million barrels of oil, valued at about US$1.7 billion. To do this, the company and its partners allegedly transferred oil from ship to ship at sea, forged documents, painted ships with new identities, and falsified tracking signals — all to avoid any trace of their relations with Iran.

El Comercio explored social problems in the province of Condorcanqui, in the Peruvian Amazon, such as violence against women and teenage pregnancy, and showed how a group of women from the Awajún Indigenous people have been working to protect girls and educate communities with the support of members and leaders. According to the report, the number of pregnant girls and teenagers has soared in the past decade in the region. Through an interactive visualization, the team presented data on cases of sexual violence reported to the Women’s Assistance Centers (CEM), highlighting those committed against minors under 18 years of age, the number of complaints received by the Awajún Women’s Council, and the national figures for pregnant teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19.

This year, Nikkei’s data teams have dug into the last words of North Korean soldiers killed in Russia, terrorism on the Tokyo subway, Vietnam’s economic growth, and a possible heir apparent into Kim Jong Un in Pyongyang. This visual investigation into scam centers in Myanmar dug into the clandestine compounds where trafficked workers are forced into “pig butchering,” a type of online investment scam that entails building online relationships with victims and tricking them into fake investment schemes. Nikkei’s Vdata team combined satellite imagery, night-time light analysis, public records, expert interviews, and NGO reports to identify and verify suspected scam centers, which are often built along the borders with Thailand, where many workers are from. The team pinpointed the precise locations of these hubs on the borders of Myanmar, revealing how they’ve grown into “prisons” ensnaring those who think they’ve been offered a job but instead find themselves trapped in money-driven exploitation schemes.

Hanna Duggal is the writer of GIJN’s fortnightly Top Ten in Data Journalism column, and a data journalist at AJ Labs, the data, visual storytelling, and experiments team of Al Jazeera. She has reported on issues such as policing, surveillance, and protests using data, and reported for GIJN on data journalism in the Middle East, investigating algorithms onTikTok, and on using data to investigate tribal lands in the US.

2025-12-18 16:00:37

Investigative journalism in Turkey has shown remarkable resilience, depth, and impact this year, even though the operating conditions remain difficult and political pressures, limited access to information, and threats to press freedom all weigh heavily on the reporters working in this field.

The country is currently languishing in 158th position (out of 180) in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, with 90% of national media now under government control, “almost systematic online censorship, arbitrary lawsuits against critical media outlets, and the exploitation of the judicial system” all posing serious challenges for independent reporters, the RSF report noted.

But as the stories chosen for this list demonstrate, in everything from digging into environmental disasters to investigating human rights abuses, and from exposing financial corruption to uncovering digital surveillance, independent reporting still remains a vital presence in the country.

Standout environmental reporting this year includes a multi-part investigation into the lack of oversight and resulting disasters at a gold mine in eastern Turkey and a deep look at corporate lobbying to water down EU regulations on so-called forever chemicals.

Investigations into social and institutional crises in Turkey include one on a crisis of suicide among police officers, alleged sexual misconduct in the nonprofit sector, and an exposé into money laundering. An investigation into neglect and abuse suffered by Ukrainian orphans brought to Turkey revealed shortcomings in humanitarian aid projects. Finally, investigations into digital surveillance, such as AI-powered protest monitoring and on EU-funded surveillance technologies, underscore the tension between technological advancement and civil liberties.

Across these stories, a common thread emerges: investigative journalists play an essential role in exposing abuses, protecting democratic values, and ensuring that public accountability extends to the powerful and the vulnerable alike. These 2025 investigations are a testament to both the courage and the craft of the country’s investigative reporters.

This multi-part investigation by Ortak’s investigative journalism team and published by online newspaper T24 is the product of months of fieldwork. Its comprehensive reporting on the Erzincan-İliç Çöpler gold mine reveals a lack of effective government oversight, the social impact of the mine on nearby villages, and an investigation into the causes of a landslide in February 2024 that claimed the lives of nine workers.

Reporters use the intertwined story of two villages — Çöpler and Sabırlı — to delve into the impact of the mining operation. A turning point, they pointed out, came after a cyanide leak that polluted land near the Euphrates river. Although the mine was shut down for 88 days after the leak was detected, operations resumed in September 2022 — despite persistent objections from residents and experts.

The reporters conducted more than 100 interviews with residents, with workers and former employees of the gold company and its subcontractors; with ministry officials and local administrators responsible for oversight; and with experts tracking mining activities across Turkey. Location-based before-and-after maps allowed the team to document how the region’s landscape has been historically transformed. A network analysis map showed the relationships between all the actors involved — such as contractors, subcontractors, companies, and individuals.

As a result of the investigation, prosecutors have opened criminal investigations for negligent homicide and environmental crimes, and civil society organizations have filed complaints. The issue has been discussed in Parliament, and the mine is currently non-operational — the future of the project is uncertain.

This investigation by independent nonprofit outlet The Black Sea explored the Turkish entities involved in an extraordinary lobbying effort to influence European Union lawmakers as they mull over a ban on “forever chemicals.” Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals linked to health and environmental harms because they do not break down in nature. This report reveals a far-reaching and highly coordinated attempt by PFAS manufacturers and industrial users to influence EU regulators at a critical moment — as the bloc considers a historic ban on thousands of PFAS compounds.

The investigation suggests companies have misrepresented scientific data, deployed disinformation strategies, and engaged in extensive political lobbying to weaken or delay restrictions designed to curb exposure to PFAS. In Turkey, PFAS contamination is evident but poorly documented. The investigation found that the chemicals have been detected in rivers, lakes, fish, and even drinking water, while several regions show signs of potential long-term pollution.

Protests following the arrest of the Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu were met with sweeping detentions. Image: Shutterstock

This investigation in New Lines Magazine exposed how Turkish authorities are expanding AI-driven surveillance and facial recognition policing while circumventing legal safeguards designed to protect basic rights.

After the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu in March 2025, nationwide protests were met with sweeping detentions: roughly 2,000 people were taken into custody, and 239 were formally imprisoned. This story notes that protesters were frequently identified through police-operated facial recognition systems, street cameras, body-worn devices, and social media footage. In many cases, the mere act of being physically present at a demonstration — or even wearing a medical mask — was treated as incriminating evidence.

The investigation details how Turkey has rapidly expanded this surveillance architecture. The findings — obtained by combining witness testimony with documentary evidence and cross-referencing official procurement and police reports — reveal a pattern: hundreds of protesters detained in early-morning raids; dozens prosecuted and held in pretrial detention although authorities presented no credible evidence of weapons, violence, or criminal intent. What emerges, the investigation argues, is a systemic “surveillance-and-prosecution machine” that converts ordinary civic participation into criminal liability.

This BBC News Turkish investigation led to the arrest of the head of a refugee aid charity in Ankara, after multiple Syrian women accused him of sexually exploiting them in exchange for aid. The women — who approached his organization, Umut Yardımlaşma Derneği, in moments of extreme vulnerability — said that while the aid official initially presented himself as a benefactor, he later used their desperation to coerce, intimidate, and assault them.

In the report, three women shared detailed accounts of harassment and assault, alleging that he groped them, forced unwanted contact, tried to coerce sexual acts, and threatened to have them deported if they resisted. Their testimonies were echoed by seven additional individuals, including former employees, who said they witnessed or heard about similar abuse occurring between 2016 and 2024. Despite past allegations, earlier cases were dropped because the alleged victims were too afraid to file formal complaints.

Following the BBC’s investigation, more women came forward, providing testimonies that resulted in formal charges and the man was subsequently arrested and is now awaiting trial in jail. He denies the allegations, insisting that his charity has helped tens of thousands of refugees over the past decade and suggesting a medical condition he has made some of the allegations implausible.

In December 2023, four boats carrying Syrian migrants set off from the Lebanese port city of Tripoli. Three of them managed to reach Cyprus. The fourth — the Princess Lulu — carrying 85 people, including 35 children, vanished in the night. Despite desperate pleas from families, warnings from volunteer monitoring networks, and final messages sent by passengers, no search-and-rescue operation was launched, and no official investigation was opened. Weeks later, bodies started washing ashore. Around 20 corpses were found along the coasts of Turkey, northern Cyprus, and Syria.

During fieldwork in Turkey, Cyprus, and Lebanon, The Black Sea team reached the relatives of the missing as well as key figures within the smuggling networks. The investigation revealed a multi-layered trafficking chain in Tripoli, in which families paid thousands of dollars; a last-minute crew change; a poorly maintained and faulty vessel; and suspicions — raised by some witnesses — that the boat may have been carrying drugs. Smugglers tried to stall families in the early days by claiming “everyone made it to Cyprus,” while attempting to release the cash deposits they still held. The passengers’ final videos show people clinging to unsafe rubber rings. Dozens of families are still waiting for answers and accountability.

This Fayn Press investigation exposed the structures and processes of money laundering in Turkey and provides an in-depth look at how the state and private sectors intersect. A beauty salon owner and her husband, known for their flashy lifestyles on social media, are reported to be at the center of these operations and face several charges related to alleged money laundering, illegal gambling, and tax violations. They have both denied the accusations. Prominent companies in the fintech, luxury hotel, and media fields are also implicated.

The team started by looking at publicly available court records and procurement data and cross-referenced these documents with corporate registries, offshore databases, and leaked materials to uncover ownership structures, proxy companies, and political connections, using digital mapping tools to connect these complex relationships. The investigation highlighted the 2016 Asset Amnesty Law as a factor that has made Turkey an attractive hub for laundering, with billions of dollars from illegal activities such as drug and human trafficking, smuggling, gambling, prostitution, and organ trade reportedly being funneled into the economy.

This three-part investigation for the online news media site Kısa Dalga revealed that there has been a sharp rise in police suicides in Turkey in recent years, and delved into the shortcomings of official inquiries and the institutional dynamics that allow the crisis to persist. According to official figures, more than 450 police officers have taken their own lives in the past five years, and over 1,000 in the past two decades — yet most cases are swiftly closed without any meaningful investigation.

Part 1 of the report outlined the scale of the problem, the increase in the number of suicide cases, and the many unanswered questions raised by families. Part 2 examined how suicide cases are improperly handled, with phone records and witness statements not properly reviewed; and commanding officers rarely facing consequences for problems among their staff. Part 3 showed that police suicides do not stem from a single cause but from a “chain of exhaustion.” Low wages, soaring rents, grueling shift systems, command pressures, and unlawful orders, all contribute — with the investigation underscoring how police suicides are the result of structural problems, not individual ones.

This report by the Turkish fact-checking organization Teyit highlighted how bots, troll networks, and algorithm-driven content flows amplify climate denial, eroding public trust in science and directly weakening climate action. It focused particularly on the policies of platforms such as X, YouTube/Google, Meta, and TikTok, revealing a significant gap between the official rules these companies proclaim and how they are implemented in practice. The team found that while some platforms have developed policies to curb climate disinformation, their effectiveness remains limited. For example, mechanisms like X’s Community Notes often label a false statement as misinformation only after it has already spread, while Meta’s termination of independent fact-checking collaborations in the US in 2025 further weakened oversight.

The investigation drew together analyses of platform policies and enforcement, academic research, and monitoring of algorithmic behavior, and found that social media platforms have been inconsistent and largely ineffective in combating climate disinformation.

Chain of Neglect and Abuse Targeting Ukrainian Orphans Brought to Turkey

Under the Childhood Without War project run by a Ukrainian charitable foundation, 510 children were transferred from orphanages in eastern Ukraine to Turkey in 2022 and temporarily housed in a hotel in Antalya. After reporters from Ukrainian outlet Slidstvo, Investigate.cz, and OCCRP published an article based on a monitoring report from Ukraine’s Ombudsman Office that described conditions at the hotel, a team at Turkish weekly newspaper Agos conducted its own series of investigations into the issue. They found that the children’s basic needs, including shelter, nutrition, hygiene, medical care, and security, were not adequately met. Observations from oversight teams suggested systematic neglect, and more serious claims concerned sexual abuse and forced labor. The investigation reported that at least two hotel staff members were accused of engaging in sexual relations with underage girls, resulting in pregnancies, after which the children were sent back to Ukraine. Additionally, children were allegedly forced to perform tasks such as cleaning, caregiving, and assisting disabled peers — responsibilities far beyond their age. One child disappeared.

In an interview with Slidstvo, the Ukrainian businessman behind the organization stated that he and his team had “done the best possible job under difficult circumstances” and that the conclusions of the Ombudsman’s report were “faulty.”

The impact of this investigation was far-reaching. In Turkey, many outlets picked up Agos’ reporting; authorities announced that the hotel would face further scrutiny; and the Turkish ministry in charge of child welfare opened an investigation. But official inquiries in both Turkey and Ukraine have since closed, citing insufficient evidence.

This Follow the Money investigation examined how some firms supplying surveillance and facial recognition technology to the Turkish government are — or have been — recipients of European Union research funds, raising serious questions about whether EU money indirectly supports authoritarian surveillance. The investigation analyzed police reports, court documents, government tenders, company financial reports, and EU funding databases, and included interviews with protestors, lawyers, human‑rights experts, and a member of the European Parliament.

Reporters found evidence of several Turkish firms that had previously received EU research funds, providing technologies used to monitor and prosecute anti-government protesters. The report suggests that European taxpayers’ money may be contributing — even indirectly — to surveillance infrastructure that suppresses dissent and civil liberties in a non‑EU country.

Pınar Dağ is the editor of GIJN Turkish and a lecturer at Kadir Has University. She is the co-founder of the Data Literacy Association (DLA), Data Journalism Platform Turkey, and DağMedya. She works on data literacy, open data, data visualization, and data journalism and has been organizing workshops on these issues since 2012. She is also on the jury of the Sigma Data Journalism Awards.

Pınar Dağ is the editor of GIJN Turkish and a lecturer at Kadir Has University. She is the co-founder of the Data Literacy Association (DLA), Data Journalism Platform Turkey, and DağMedya. She works on data literacy, open data, data visualization, and data journalism and has been organizing workshops on these issues since 2012. She is also on the jury of the Sigma Data Journalism Awards.

2025-12-17 16:00:17

This year, GIJN’s Resource Center team produced a wide variety of guides on everything from investigating climate change to reporting on AI, from digging into Chinese companies to probing evidence of war crimes, and from covering food insecurity to looking at land conflict. The Resource Center is full of material relevant for investigative reporters. The archive now holds more than 2,000 items in 14 languages — from tipsheets and guides to instructional videos. Here are our top selections for this year.

With fossil fuels accounting for more than 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90% of all carbon dioxide emissions, GIJN recruited five top climate journalists to share their knowledge and expertise on how to enable better investigations of private and state-owned fossil fuel companies, how to uncover lobbying efforts that influence climate policies, and how to expose greenwashing and disinformation within the industry. The guide also touched on how to analyze government regulations and policies affecting the fossil fuel sector, and how to report on the climate solutions proposed by the fossil fuel industry.

Continuing a cutting-edge series of climate guides, GIJN advisor Toby McIntosh focused on the importance of investigating methane emissions from waste sites. This guide equips reporters who want to cover the climate and health impacts of methane from landfills, a major but overlooked source of greenhouse gas. It explains how to detect emissions using satellite data and on-the-ground reporting, offers key questions to evaluate mitigation measures, and highlights practical solutions — from biogas capture to composting — and real-world case studies. This resource helps journalists hold waste management systems accountable and elevate local reporting.

The number of people facing acute, life-threatening hunger nearly tripled in the last decade to 295 million across 53 countries, according to the 2025 Global Report on Food Crises. Conflict was the leading driver, followed by economic shocks and weather extremes. Yet food insecurity remains a challenging issue for journalists to investigate.

With their combined experience, award-winning journalists Thin Lei Win and Deborah Nelson put together a reporting guide to help journalists understand the causes of food inequity, famine, and starvation. They also break down technical terms and classification for journalists, pointing them to resources where they can find data and identifying areas that journalists can investigate further.

Scarcity of land in South Asian countries naturally leads to domestic conflicts between local communities, businesses, the political class, and the government when it comes to the use and ownership of land and its natural resources. These often escalate into conflicts that specifically affect marginalized communities, clog courts, and freeze big investments.

This guide helps journalists answer basic questions, such as: What is causing land resource conflicts? What is the scale of its impact? Who is impacted? Who are the actors involved and how do their motivations shape these conflicts? It also equips journalists with the tools and resources they need to report on land conflicts in a region that hosts nearly a quarter of the global population.

This GIJN guide empowers journalists globally to uncover and report on efforts by foreign entities to influence policy. It surveys international lobbying laws and databases — from the US to Latin America and beyond — and offers practical instructions on how to find disclosures, map actors, analyze influence strategies, and use public records. The guide features recent cases such as Azerbaijan’s “caviar diplomacy,” and secret lobbying on behalf of Qatar, and equips reporters with tools to expose hidden lobbying networks and hold power to account.

Caste can be a taboo issue in India and other South Asian countries — but this guide provides insight into the caste system’s complexities and offers practical advice on reporting caste-related stories effectively. It provides background information on how caste shapes social, political, andfifani economic inequalities, especially in India. In addition, it outlines methods for gathering documentation, conducting interviews, and identifying systemic bias. With practical advice on sourcing data and navigating ethical risks, this guide empowers journalists to produce informed, impactful coverage of caste dynamics and marginalized communities.

Covering social media algorithms can take many forms. Not only are algorithms on social media deeply complex, but the companies that produce them rarely disclose how they work. This guide helps journalists examine how opaque platform rules can shape misinformation, hate speech, and user experiences. It explains algorithm basics and media ecosystem dynamics, plus offers practical approaches — such as reverse engineering, content tracing, and experiments — to uncover harms. Featuring global case examples, the guide empowers reporters to hold social media companies accountable and reveal the impact of unseen algorithmic influence.

We’re approaching a point where the signal-to-noise ratio is getting close to one, meaning that as the pace of misinformation approaches that of factual information, it’s becoming nearly impossible to tell what’s real. In this guide, renowned trainer Henk Van Ess guides journalists through the process of identifying probable AI-generated content under deadline pressure, offering seven advanced detection categories that every online reporter needs to master. This was GIJN’s most popular guide for 2025.

As China emerges as a global superpower, with a population of 1.4 billion people and the world’s second-largest economy, Chinese corporate activities, government policies, and international investments directly impact stories across every beat. Despite a demand for reliable information, the landscape for international reporting from China has dramatically deteriorated in recent years.

This guide introduces journalists to open data needed for any China-related investigations, from public databases to government resources and corporate self-disclosures and legal and judicial documents. The guide provides insight into navigating the information ecosystem within China.

Palestinians facing famine gather to receive meals from the nonprofit organization Rafah Charitable Kitchen, in Khan Yunis, in the southern Gaza Strip, on January 2025. Image: Shutterstock

GIJN’s war crimes guide, originally published in 2023, now has three new chapters on prescient topics: the arms trade, forced displacement, and starvation. These chapters will assist journalists in investigating when an arms-exporting country is complicit in war crimes and crimes against humanity, when forced displacement can be prosecuted as an international crime, and when food is used as a weapon of war. The guide is also available as an e-book in multiple online bookstores.

With the help of GIJN’s network of 14 regional editors, resource center researcher Emily O’Sullivan put together a list of scholarships from universities and training organizations around the world. The list of funding opportunities applies to courses focused on investigative or data journalism, as well as journalism degrees with an investigative or data module.

Amel Ghani is a journalist based in Pakistan, and GIJN’s Resource Center researcher and Urdu editor. She has reported on various issues, from writing about the rise of religious political parties, the environment, labor rights, to covering tech and digital rights. She is a Fulbright Fellow and holds a Master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, where she specialized in investigative journalism.

Amel Ghani is a journalist based in Pakistan, and GIJN’s Resource Center researcher and Urdu editor. She has reported on various issues, from writing about the rise of religious political parties, the environment, labor rights, to covering tech and digital rights. She is a Fulbright Fellow and holds a Master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, where she specialized in investigative journalism.

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. She has been writing and producing documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for more than 18 years, working with outlets including the BBC, The Associated Press, AJ+, and The New York Times, among others. She covered Greece’s economic crisis, reported on the European migrant crisis, and her documentaries have been screened in festivals across the world. She is a graduate of Columbia University and Panteion University, in Athens, Greece.

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. She has been writing and producing documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for more than 18 years, working with outlets including the BBC, The Associated Press, AJ+, and The New York Times, among others. She covered Greece’s economic crisis, reported on the European migrant crisis, and her documentaries have been screened in festivals across the world. She is a graduate of Columbia University and Panteion University, in Athens, Greece.

2025-12-16 16:00:01

The investigative stories produced in the Spanish-speaking world this year show a vibrant journalistic landscape, despite the challenges reporters now face in many places — from rampant disinformation to job insecurity, and from threats against independent reporters to declining public trust in journalism and news outlets.

Our selection takes you from an investigation into missing children caught up in an internal conflict in Ecuador to Spain, where investigative reporters examined the role of algorithms in healthcare; and from a tool that allows readers to examine the intersection of wealth and power in Peru to Paraguay, where journalists uncovered clandestine airstrips. We also feature a collaboration that uncovered the influence of big tech in Latin America and how it is shaping people’s lives.

These stories highlight the strength of the investigative journalism community, yet the risks are growing. According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), journalism across the Americas is facing a crisis. This year’s World Press Freedom Index found that news outlets in the region are dealing with “persistent structural and economic challenges,” rising authoritarianism in many places, and press freedom challenges.

“As journalism’s public service role is degraded, propaganda and disinformation fill the void — threatening the region’s democracies,” the authors warned.

But investigative journalists in the region are rising to the challenge. And while it is almost impossibly hard to highlight just eight pieces for the last year that show the scale, breadth, and power of investigative reporting in the Spanish language, the stories selected here prioritized variety in content, location, and format.

This nine-month investigation, covering 13 countries, goes deep into how major technology companies have been working to create a “web of influence” to shape public policy and profit from weak regulations across Latin America. The stories and data reveal the scale of lobbying and litigation by big tech companies and their allies — and how it blocks policies that could curb online harms. Led by Agência Pública (Brazil) and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), the investigation involved an additional 15 media outlets in a collaborative transnational effort. Together, they mapped nearly 3,000 lobbying activities targeting governments and parliaments across the region, tracing lawsuits and legislative proposals alike. The project also delves into the environmental toll of the sprawling data centers being set up across the continent. Readers can access the findings in an interactive database that weaves rigorous data with compelling storytelling.

Renowned Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui and her team of investigative reporters received a huge trove of leaked data that led them to report on a covert operation at the Mexican broadcasting giant Televisa, where members of a secret division were allegedly tasked with fabricating news and destroying reputations. The leak consisted of more than five terabytes of internal communications, including videos, photos, WhatsApp messages, and scripts that reporters said showed evidence of smear campaigns orchestrated from the headquarters of the television company. The leaked information describes an internal team in Televisa’s headquarters known as “Palomar,” which was said to have the objective of manipulating public opinion with fake videos, bots, and fake social media profiles, and discrediting individuals or companies to advance Televisa’s interests. Aristegui was also one of the targets, with her name appearing nearly 300 times. The investigation earned second place in the Javier Valdez Award at COLPIN 2025, the Latin American Conference on Investigative Journalism. Televisa has not issued an official statement on the leaks or about the subsequent departure of one of its vice presidents.

This investigation reads like a journalistic chronicle, an account by the reporters of their journey to a desolate area in Paraguay where there is no phone service and there are no paved roads — but a thriving trade in narcotics.

In the past, owning a weapon in this area was necessary to defend livestock from wild animals, one local source told them. Now, they are more worried about the drug traffickers.

Reporters for El Surtidor and OCCRP describe how Paraguay’s Chaco region has become a major hub for international drug trafficking, with clandestine airstrips used to move cocaine from Bolivia to Brazil, Paraguay, and beyond. Despite government interventions, these tracks are rebuilt or replaced, showing failures in enforcement. The Chaco’s remoteness, harsh terrain, and lack of radar coverage make it ideal for criminal operations, while local communities, including Indigenous groups and Mennonites, are caught between illegal activity and violence.

The border region between Colombia and Venezuela has long been porous, complicated, and dangerous. But this investigation explores the dangers of the crossing, and the crisis of missing people who have disappeared in the segment of the border region extending from La Guajira to the Arauca River. Reporters from Armando.info and Vorágine visited several hotspots on both sides of the border, where they confirmed the crisis of the missing. They portray an expanding and largely unspoken situation in areas dominated by criminal networks from both nations and along uncontrolled smuggling corridors. The piece highlights that while Colombian authorities have attempted to document and search for some of the disappeared, Venezuela’s government has responded with indifference, leaving families without answers. See Cartography of Horror, an illustrated story from the investigation.

Peru: Street Wayki

In an effort to document the wealth of Peru’s leading politicians, investigative reporters from Ojo Público created Street Wayki — a game-like application that is also a valuable resource for journalists tracking money flows, conflicts of interest, and power networks across Peru’s political system. The platform allows users to compare the wealth of the president, members of Congress, and the country’s regional governors, revealing, for instance, how top authorities have significantly increased their assets while in office. It also highlights cases of lawmakers who reported no assets as candidates but now declare holdings worth hundreds of thousands of soles, detailed alongside any complaints, investigations, and judicial processes they currently face. The application was developed by a multidisciplinary team made up of journalists, developers and data analysts, who built the databases through requests for access to information, data extraction from public portals via scrapping, and access to tax and judicial files.

Soldiers accused of forcibly removing teenagers from their homes. Mothers looking for their lost children. Drug gangs forcibly recruiting. Investigations going nowhere.