2025-12-30 21:00:00

Nowadays, having a New Year’s resolution can seem almost quaint. Social-media influencers push self-improvement trends year-round: The spring has “glow up” challenges, as does the summer. Soon after, the high-discipline “Great Lock-In Challenge” and “Winter Arc” videos begin, many of them urging people to get ahead of the “new year, new me” crowd. Or you can attempt a slew of other self-betterment regimens, whenever the spirit calls. Many of these videos depict people minimizing distractions—such as, say, other people—to bicep-curl and matcha-drink their way to becoming “unrecognizable,” mentally and physically, as some YouTubers put it. At the same time, many Americans appear to be losing interest in New Year’s resolutions. One report from the social-media analytic company Brandwatch found that, in the days around January 1, mentions of resolutions fell 50 percent last holiday season when compared with the year prior. To put it plainly: Many people are now always trying to hustle their way to a better self, no matter the month or season.

In one sense, detaching goal setting from the start of the Gregorian calendar is reasonable—one can, of course, choose to begin afresh at any moment. But by letting New Year’s resolutions go, Americans may be losing something: a distinctly communal ritual that can remind people of how entangled their well-being is with that of others.

New Year’s hasn’t always been so associated with accomplishing personal goals. Humans have a long history of using the holiday to think about how to make life better for their community. Versions of resolutions have existed for about 4,000 years; in Babylonia and ancient Rome, people prayed together, paid off their debts, and made promises of good conduct to their gods. The rituals were usually framed as religious events supporting the broader group, and were tied to agricultural calendars. (“Permit my harvests, my grain, my vineyards, and my plantations to flourish,” some ancient Romans were counseled to ask of Janus, the god of transitions and beginnings, “and give good health and strength to me, my house, and my household.”) Even in the more recent past, in the United States, many people’s resolutions focused on learning how to live well with others. The most popular resolution in the U.S. in 1947 was, according to a Gallup poll, to “improve my disposition, be more understanding, control my temper.” Last year, by contrast, Americans’ resolutions were primarily related to exercise, health, or diet.

[Read: Americans need to party more]

Americans may no longer share a schedule dictated by the agricultural calendar, but a sense of community doesn’t need to disappear. New Year’s can be an opportunity to gather with loved ones and set resolutions together. Maybe everyone meets in person; maybe over Zoom. Maybe the group sets one big, collaborative goal—Let’s start a community garden, for instance, or Let’s take turns cooking meals for one another at home. Maybe everyone picks a different resolution, and the group brainstorms how to best help each person achieve it. And ideally, the goals aren’t self-serving—but considerate of the people around them.

Making a resolution with other people might actually be more effective than flying solo. Habits are unconscious patterns that can be hard to shake, and seeing someone in our environment engaging in a certain behavior can nudge us to do it too, Tim Kurz, a psychology professor at the University of Western Australia, told me. This permeability can have its downsides—your sister’s Is It Cake? binge-watching in the living room could cue you to watch even more Netflix. But it can also be a great boon: As work piles up, for example, you might forget about your resolution to check in on older family members. If you have set this intention as a household, though, you might see your partner buying groceries for their grandmother, which in turn might remind you to call grandma too.

Shared resolutions can support intention setting in another way: They may help people avoid what social psychologists call “do-gooder derogation”—a quirk of psychology in which humans tend to “find people who are more moralistic than us and are behaving more virtuously than us really annoying,” Kurz said. He gave me this example: Say you’ve recently resolved to ride your bike to work instead of driving, for environmental reasons. Your family, already buckled into the SUV, might feel their virtue threatened and decide to poke fun at you. Look at this guy! Have fun biking in the rain, Goody Two-shoes! If you set goals as a family, however, your relatives—who under other circumstances might be psychologically motivated to subvert your resolutions—may become more committed to helping you follow through.

[Read: Invisible habits are driving your life]

In the long run, resolutions that keep others in mind tend to have greater staying power. Studies have found that brute willpower alone lasts for only so long, and that people have a much harder time accessing willpower when stressed. This might help explain why a more individual New Year’s goal, such as losing 10 pounds by swearing off ice cream, may be more likely to fizzle. “If you fail in your quest, then the only person you have ‘let down’ is yourself,” Kurz said. Evolutionarily speaking, people might not even be built to set self-serving goals. What helped our human ancestors succeed were likely “strong social bonds,” the psychologist David Desteno wrote in a New York Times article about resolutions, “relationships that would encourage people to cooperate and lend support to one another.”

Of course, shared resolutions aren’t a magic pill for behavioral change. Humans can famously be both top-notch accountability partners and rampant enablers. When picking whom to make goals with, “be careful about who that person is,” Kurz told me. “You don’t want to strategically choose the person who you know is a total flake.” You might have resolved with your work bestie to quit overdoing the happy-hour piña coladas so that you can better participate in your team’s conversations; if your pal capsizes on your shared goal first, though, their decision could lead to a cycle of “collective rationalization,” in which you feel okay quitting too, Kurz told me. Hell, why not get another round?

Still, communal resolutions can serve as a good reminder of how profoundly interconnected humans are. And they can push people to widen their definition of self-improvement. In a recent interview, the Potawatomi botanist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer described the concept of “expanded self-interest”—the idea that the “self” can include all of life. “My well-being is the same as my family’s well-being,” she explained, and “my family’s well-being is the same as the well-being of the land that feeds us.” Bicep curls and matcha lattes, then, may get us only so far on the path to flourishing. The trick to helping ourselves might just be to focus on the communal first.

2025-12-30 21:00:00

For all of the political chaos that American science endured in 2025, aspects of this country’s research enterprise made it through somewhat … okay. The Trump administration terminated billions of dollars in research grants; judges intervened to help reinstate thousands of those contracts. The administration threatened to cut funding to a number of universities; several have struck deals that preserved that money. After the White House proposed slashing the National Institutes of Health’s $48 billion budget, Congress pledged to maintain it. And although some researchers have left the country, far more have remained. Despite these disruptions, many researchers will also remember 2025 as the year when personalized gene therapy helped treat a six-month-old baby, or when the Vera C. Rubin Observatory released its first glimpse of the star-studded night sky.

Science did lose out this year, though, in ways that researchers are still struggling to tabulate. Some of those losses are straightforward: Since the beginning of 2025, “all, or nearly all, federal agencies that supported research in some way have decreased the size of their research footprint,” Scott Delaney, an epidemiologist who has been tracking the federal funding cuts to science, told me. Less funding means less science can be done and fewer discoveries will be made. The deeper cut may be to the trust researchers had in the federal government as a stable partner in the pursuit of knowledge. This means the country’s appetite for bold exploration, which the compact between science and government supported for decades, may be gone, too—leaving in its place more timid, short-term thinking.

In an email, Andrew Nixon, the deputy assistant secretary for media relations at the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the NIH, disputed that assertion, writing, “The Biden administration politicized NIH funding through DEI-driven agendas; this administration is restoring rigor, merit, and public trust by prioritizing evidence-based research with real health impact while continuing to support early-career scientists.”

Science has always required creativity—people asking and pursuing questions in ways that have never been attempted before, in the hope that some of that work might produce something new. At its most dramatic, the results can be transformative: In the early 1900s, the Wright brothers drew inspiration from birds’ flight mechanics to launch their first airplanes; more recently, scientists have found ways to genetically engineer a person’s own immune cells to kill off cancer. Even in more routine discoveries, nothing quite matches the excitement of being the first to capture a piece of reality. I remember, as a graduate student, cloning my first bacterial mutant while trying to understand a gene important for growth. I knew that the microscopic creature I had built would never yield a drug or save a life. But in the brief moment in which I plucked a colony from an agar plate and swirled it into a warm, sugar-rich broth, I held a form of life that had never existed before—and that I had made in pursuit of a question that, as far as I knew, no one else had asked.

Pursuing scientific creativity can be resource intensive, requiring large teams of researchers to spend millions of dollars across decades to investigate complex questions. Up until very recently, the federal government was eager to underwrite that process. Since the end of the Second World War, it has poured money into basic research, establishing a kind of social contract with scientists, of funds in exchange for innovation. Support from the government “allowed the free play of scientific genius,” Nancy Tomes, a historian of medicine at Stony Brook University, told me.

The investment has paid dividends. One oft-cited statistic puts the success of scientific funding in economic terms: Every dollar invested in research and development in the United States is estimated to return at least $5. Another points to the fact that more than 99 percent of the drugs approved by the FDA from 2010 to 2019 were at least partly supported by NIH funds. These things are true—but they also obscure the years or even decades of meandering and experimentation that scientists must take to reach those results. CRISPR gene-editing technology began as basic research into the structure of bacterial genomes; the discovery of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs depended on scientists in the late ’70s and ’80s tinkering with fish cells. The Trump administration has defunded research with more obvious near-term goals—work on mRNA vaccines to combat the next flu pandemic, for instance—but also science that expands knowledge that we don’t yet have an application for (if one even exists). It has also proposed major cuts to NASA that could doom an already troubled mission to return brand-new mineral samples from the surface of Mars, which might have told us more about life in this universe, or nothing much at all.

Outside of the most obvious effects of grant terminations—salary cuts, forced layoffs, halted studies—the Trump administration’s attacks on science have limited the horizons that scientists in the U.S. are looking toward. The administration has made clear that it no longer intends to sponsor research into certain subjects, including transgender health and HIV. Even researchers who haven’t had grants terminated this year or who work on less politically volatile subjects are struggling to conceptualize their scientific futures, as canceled grant-review meetings and lists of banned words hamper the normal review process. The NIH is also switching up its funding model to one that will decrease the number of scientific projects and people it will bankroll. Many scientists are hesitant to hire more staff or start new projects that rely on expensive materials. Some have started to seek funds from pharmaceutical companies or foundations, which tend to offer smaller and shorter-term agreements, trained more closely on projects with potential profit.

All of this nudges scientists into a defensive posture. They’re compressing the size of their studies or dropping the most ambitious aspects of their projects. Collaborations between research groups have broken down too, as some scientists who have been relatively insulated from the administration’s cuts have terminated their partnerships with defunded scientists—including at Harvard, where Delaney worked as a research scientist until September—to protect their own interests. “The human thing to do is to look inward and to kind of take care of yourself first,” Delaney told me. Instability and fear have made the research system, already sometimes prone to siloing, even more fragmented. The administration “took two of the best assets that the U.S. scientific enterprise has—the capacity to think long, and the capacity to collaborate—and we screwed them up at the same time,” Delaney said. Several scientists told me that the current funding environment has prompted them to consider early retirement—in many cases, shutting down the labs they have run for decades.

Some of the experiments that scientists shelved this year could still be done at later dates. But the new instability of American science may also be driving away the people necessary to power that future work. Several universities have been forced to downsize Ph.D. programs; the Trump administration’s anti-immigration policies have made many international researchers fearful of their status at universities. And as the administration continues to dismiss the importance of DEI programs, many young scientists from diverse backgrounds have told me they’re questioning whether they will be welcomed into academia. Under the Trump administration, the scope of American science is simply smaller: “When you shrink funding, you’re going to increase conservatism,” C. Brandon Ogbunu, a computational biologist at Yale University, told me. Competition and scarcity can breed innovation in science. But often, Ogbunu said, people forget that “comfort and security are key parts of innovation, too.”

2025-12-30 20:30:00

Podcasts have devastated my relationship to music. Confirmation of that sad fact came earlier this month in the form of my Spotify “Wrapped,” the streaming service’s personalized report of what I listened to this year, including a playlist of my top songs. In the past, this annual playlist supplied a loop of sonic pleasure, propelling me through workouts, dinner preps, and hours-long commutes. This year, I haven’t even opened it.

That is not to say I’ve embraced silence: According to Spotify, I spent 71,661 minutes on the app over the past 12 months. That’s 49 days. But 55,088 of those minutes were spent streaming podcasts instead of songs. Whereas I used to listen to music all the time, now I fill every available moment with the sound of people talking.

I suspect I’m not the only one. My change in listening habits comes from a compulsion that many people in my life share: to make every minute of the day as “productive” as possible. By that blinkered calculus, an informative podcast will always trump music. But listening incessantly to podcasts has actually narrowed my interests and shown me just how limiting too much information can be.

[Read: Companies’ ‘wrapped’ features keep getting weirder]

Before I finish brewing my first cup of coffee, a BBC report is already streaming from my speaker. “Not another podcast, Papa,” my son complains, wiping his sleepy eyes as I butter his toast. “I need to know what’s going on in the world,” I tell him, even though I can see how much he and his sister would rather listen to something with a beat.

After dropping him off at school, I cycle through long-form podcasts on my walk home, during my own breakfast, and as I get ready for the day. Many of these are political, and they run the ideological spectrum. I reserve The New York Times’ podcast The Daily for a short lunchtime treat. Then at the gym in the late afternoon, I’m back to eavesdropping on other people’s verbal marathons, many of them about exercise and nutrition. I used to turn on house music or jazz automatically when I started cooking in the evenings. Now I have to force myself to play anything other than chatter.

The pandemic was the turning point for me. I scarcely listened to podcasts before those days of tedium and seclusion, when overhearing a conversation almost felt like having company. The number of podcasts has exploded since then, and algorithms have deftly toured me around the new offerings. I’ve found some excellent ones; their charming and informed hosts now serve as unlikely rivals of my favorite musical artists.

The podcast boom is not the only reason I’m listening to so few songs these days. Hip-hop, the genre I grew up on, has entered a period of sustained decline. Everyone thinks the songs of their youth represent a golden era. But the rappers I listened to when I was younger really were better than today’s artists, or at least more innovative—maybe because the genre was younger, too. Dr. Dre concocted a sound that changed how the West Coast made music. Nas and Jay-Z could not only rap circles around the best of their successors; they could also smuggle some serious ideas into their hits. Consider this Socratic inquiry from Jay-Z: “Is Pius pious ’cause God loves pious?” That type of lyric rarely comes around anymore.

In the late 2010s, so-called mumble rap took off. Critics lamented that the genre—and the styles it continues to spawn—ignores lyricism and craft, a complaint that gives short shrift to the infectious exuberance these modes can produce. Still, even some of the most prominent contemporary artists worry that something has gone awry.

This fall, Billboard reported that, for the first time since 1990, its Top 40 chart didn’t contain a single rap song. Observers have proposed plenty of explanations. I favor one offered (perhaps apocryphally) by the mumble-rap pioneer Young Thug: that the enervating, yearlong feud between Drake and Kendrick Lamar degraded the genre. “Since then,” a viral quote attributed to Young Thug contends, “everyone in the world is leveling up, except hip-hop.”

In this dispiriting context, podcasts have grown all the more appealing. (Some of the best rap artists from my youth now host their own.) When I do return to hip-hop, it’s mostly to indulge my nostalgia.

[Listen: How YouTube ate podcasts and TV]

Choosing between podcasts and music reminds me of something the critic Dwight Garner observed about the value of reading a book on olive oil. “Extra Virginity is another reminder of why subpar nonfiction is so much better than subpar fiction,” Garner wrote. “With nonfiction at least you can learn something.” That’s how I used to feel about podcasts. At least they help me improve my grasp of international affairs and prepare for the AI apocalypse. BigXthaPlug and NBA YoungBoy don’t teach me anything.

But more recently, I’ve found that trying to make every listening minute count inevitably becomes counterproductive. The internal pressure to optimize free time and always multitask is ultimately exhausting, not enlightening.

The world never ceases to produce grist for discussion. That doesn’t mean we need to fill our ears with all of it. In the new year, I think I’ll try a little more silence.

2025-12-30 19:00:00

One of the first sentences I was ever paid to write was “Try out lighter lip stick colors, like peach or coral.” Fresh out of college in the mid 2010s, I’d scored a copy job for a how-to website. An early task involved expanding upon an article titled “How to Get Rid of Dark Lips.” For the next two years, I worked on articles with headlines such as “How to Speak Like a Stereotypical New Yorker (With Examples),” “How to Eat an Insect or Arachnid,” and “How to Acquire a Gun License in New Jersey.” I didn’t get rich or win literary awards, but I did learn how to write a clean sentence, convey information in a logical sequence, and modulate my tone for the intended audience—skills that I use daily in my current work in screenwriting, film editing, and corporate communications. Just as important, the job paid my bills while I found my way in the entertainment industry.

Artificial intelligence has rendered my first job obsolete. Today, if you want to learn “How to Become a Hip Hop Music Producer,” you can just ask ChatGPT. AI is also displacing the humans doing many of my subsequent jobs: writing promotional copy for tourism boards, drafting questions for low-budget documentaries, offering script notes on student films. Today, a cursory search for writing jobs on LinkedIn pulls up a number of positions that involve not producing copy but training AI models to sound more human. When anyone can create a logo or marketing copy at the touch of a button, why hire a new graduate to do it?

[From the July/August 2023 issue: The coming humanist renaissance]

These shifts in the job market won’t deter everyone. Well-connected young people with rich families can always afford to network and take unpaid jobs. But by eliminating entry-level jobs, AI may destroy the ladder of apprenticeship necessary to develop artists, and it could leave behind a culture driven by nepo babies and chatbots.

The existential crisis is spreading across the creative landscape. Last year, the consulting firm CVL Economics estimated that artificial intelligence would disrupt more than 200,000 entertainment-industry jobs in the United States by 2026. The CEO of an AI music-generation company claimed in January that most musicians don’t actually enjoy making music, and that musicians themselves will soon be unnecessary.

In a much-touted South by Southwest talk earlier this year, Phil Wiser, the chief technology officer of Paramount, described how AI could streamline every step of filmmaking. Even the director James Cameron—whose classic work The Terminator warned of the dangers of intelligent machines, and whose forthcoming Avatar sequel will reportedly include a disclaimer that no AI was involved in making the film—has talked about using the technology to cut costs and speed up production schedules. Last year, the chief technology officer of OpenAI declared that “some creative jobs maybe will go away, but maybe they shouldn’t have been there in the first place.”

One great promise of generative AI is that it will free artists from drudgery, allowing them to focus on the sort of “real art” they all long to do. It may not cut together the next Magnolia, but it’ll do just fine with the 500th episode of Law & Order. What’s the harm, studio executives might wonder, if machines take over work that seems unchallenging and rote to knowledgeable professionals?

[Read: Your creativity won’t save your job from AI]

The problem is that entry-level creative jobs are much more than grunt work. Working within established formulas and routines is how young artists develop their skills. Hunter S. Thompson began his writing career as a copy boy for Time magazine; Joan Didion was a research assistant at Vogue; the director David Lean edited newsreels; the musician Lou Reed wrote knockoff pop tunes for department stores; the filmmakers Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, and Francis Ford Coppola shot cheap B movies for Roger Corman. Beyond the money, which is usually modest, low-level creative jobs offer practice time and pathways for mentorship that side gigs such as waiting tables and tending bar do not.

Having begun my own transition into filmmaking by making rough cuts of video footage for a YouTube channel, I couldn’t help but be alarmed when the makers of the AI software Eddie launched an update in September that can produce first edits of films. For that YouTube channel, I shot, edited, and published three videos a week, and I received rigorous producer notes and near-immediate audience feedback. You can’t help but get better at your craft that way. These jobs are also where you meet people: One of the producers at that channel later commissioned my first produced screenplay for Netflix.

There’s a reason the Writers Guild of America, of which I am a member, made on-set mentorship opportunities for lower-level writers a plank of its negotiations during the 2023 strike. The WGA won on that point, but it may have been too late.

The optimistic case for AI is that new artistic tools will yield new forms of art, much as the invention of the camera created the art of photography and pushed painters to explore less realistic forms. The proliferation of cheap digital video cameras helped usher in the indie-film explosion of the late 1990s. I’ve used several AI tools in ways that have widely expanded my capabilities as a film editor.

Working from their bedrooms, indie filmmakers can deploy what, until recently, were top-tier visual-effects capabilities. Musicians can add AI instruments to their compositions. Perhaps AI models will offer everyone unlimited artistic freedom without requiring extensive technical knowledge. Tech companies tend to rhapsodize about the democratizing potential of their products, and AI technology may indeed offer huge rewards to the savvy and lucky artists who take maximum advantage of it.

[Read: Here’s how AI will come for your job]

Yet past experience from social media and streaming music suggests a different progression: Like other technologies that promise digital democratization, generative AI may be better poised to enrich the companies that develop it than to help freelance creatives make a living.

In an ideal world, the elimination of entry-level work would free future writers from having to write “How to Be a Pornstar” in order to pay their rent, allowing true creativity to flourish in its place. At the moment, though, AI seems destined to squeeze the livelihoods of creative professionals who spend decades mastering a craft. Executives in Silicon Valley and Hollywood don’t seem to understand that the cultivation of art also requires the cultivation of artists.

2025-12-30 05:30:00

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

A year ago, no one knew for sure whether Project 2025 would prove to be influential or if it would fall by the wayside, like so many plans in President Donald Trump’s first term. Today, it stands as the single most successful policy initiative of the entire Trump era.

Project 2025, which was convened by the Heritage Foundation during the Trump interregnum, was not just one thing: It was a policy white paper, an implementation plan, a recruitment database, and a worldview, all rolled into one. As I wrote in my book this past spring, the authors sought to create an agenda for the next right-wing president that would allow him to empower the executive branch, sideline Congress, and attack the civil service. The resulting politicized, quasi-monarchical government would enact policies that would move the United States toward a traditionalist Christian society.

In the roughly 11 months since he took office, Trump has closely followed many parts of Project 2025, finally embracing it by name in October. Both Trump and the plan’s architects have benefited: His second administration has been far more effective at achieving its goals than his first, and the thinkers behind Project 2025 have achieved what Paul Dans, one of its leaders, described as “way beyond” his “wildest dreams.”

Project 2025’s biggest victory has been an extraordinary presidential power grab, which has allowed Trump to act in ways that previous presidents have only fantasized about, and to act with fewer restraints. He has laid off tens of thousands of federal employees, sometimes in defiance of laws. More than 315,000 federal employees had left the government by mid-November, according to the Office of Personnel Management. Entire agencies, such as USAID, have been effectively shut down, and the Education Department may be next.

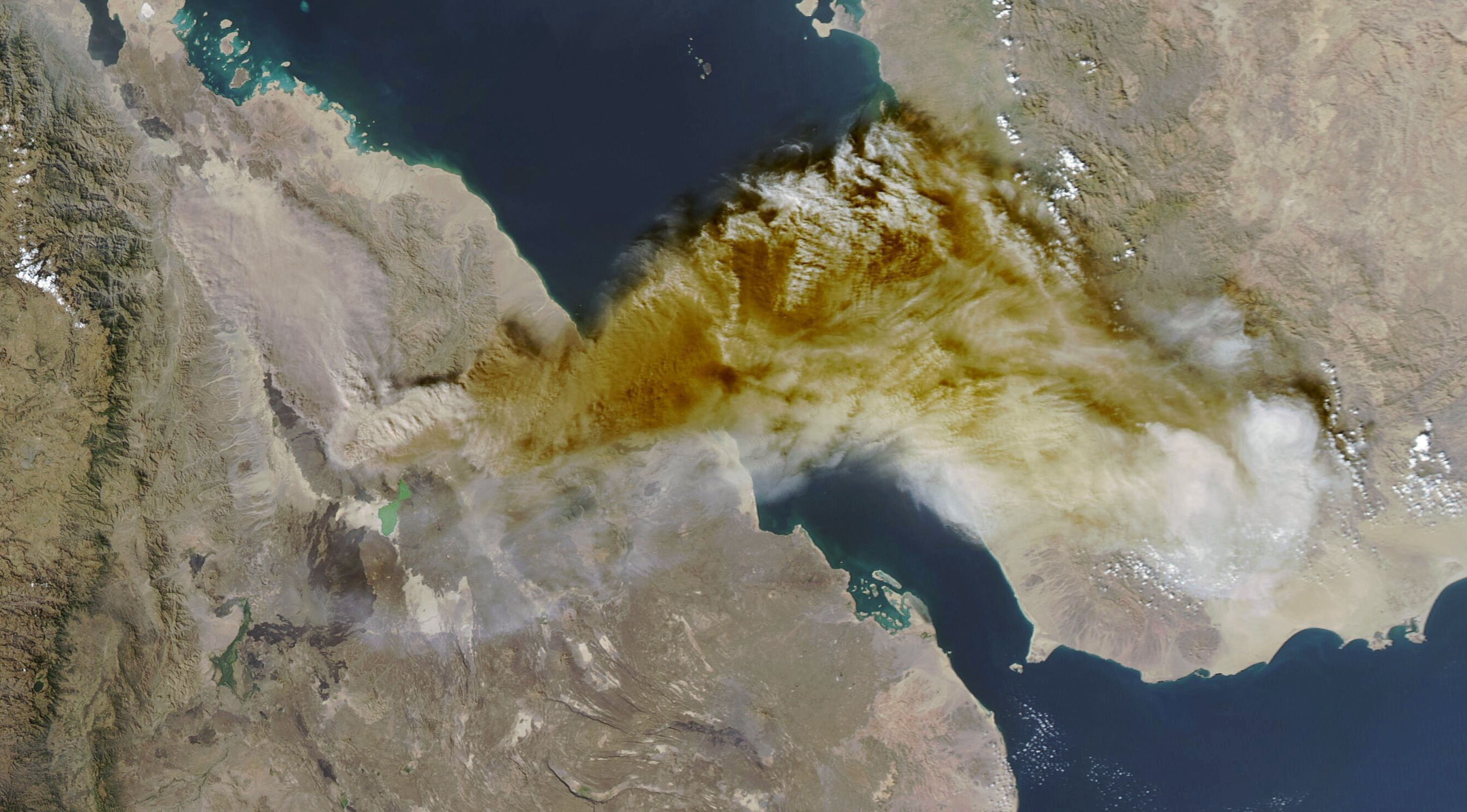

Elsewhere, the administration has slashed environmental regulations, withdrawn from a major international climate agreement, undermined renewable energy, and worked to encourage oil and gas drilling on public land. It has discarded key civil-rights-enforcement methods, dismantled anything that might be construed as DEI, and set the agenda for aggressive immigration policies, not just closing the border to many foreign nationals and deporting unauthorized immigrants but also cracking down on valid-visa holders and seeking to denaturalize citizens.

This is not small-government conservatism—it’s an effort to concentrate federal power and turn it into a political weapon. Long-standing guardrails against presidential interference in the Justice Department have been demolished. The White House has fired line prosecutors, and Trump has illegally appointed his own former personal attorneys to lead U.S. Attorney’s Offices. These prosecutors have brought charges against many of Trump’s political foes, including former FBI Director James Comey, New York Attorney General Letitia James, and Representative LaMonica McIver; others have been placed under investigation. (Judges have thrown out indictments against Comey and James, though the DOJ is appealing those dismissals. McIver, who was indicted in June for allegedly impeding federal agents and interfering with an arrest, denies wrongdoing and has pleaded not guilty.)

The administration has dabbled in impounding funds appropriated by Congress, despite a law barring this. It has also mounted a major assault on the independence of regulatory agencies, as established by Congress; Trump has fired multiple appointees, sometimes in apparent violation of law, but the Supreme Court has allowed him to proceed. Earlier this month, the justices heard arguments in a case that could overturn or severely narrow the 1935 precedent that safeguards agency independence. We already have a glimpse of what a fully politicized regulatory environment might look like: Chairman Brendan Carr, a Project 2025 author, has used his position at the Federal Communications Commission to pressure CBS News and ABC, even trying to get the late-night host Jimmy Kimmel fired earlier this year.

Trump’s presidential power grab will allow his administration to achieve more of Project 2025’s ambitions in the coming year and beyond. All of this has been enabled by a Republican-dominated Congress, which has with few exceptions allowed the president to seize legislative prerogatives, and by the Supreme Court, which has repeatedly allowed Trump to move forward on his expansion of power using the so-called shadow docket.

But Project 2025 has not been a complete success. One key belief of the authors was that Trump’s first administration was undercut by bad appointments and by failures to fill other roles. To that end, Project 2025 created a huge database of potential appointees and offered training courses. Although Trump has managed to find more aides loyal to him than in his first term, his pace of confirmation for top jobs trails the pace of most recent presidents. He has also seen a historic high in nominations withdrawn in the first year of a presidency.

More fundamentally, the Christian nationalism that courses through Project 2025 has been somewhat eclipsed by other priorities. The Trump administration has made few major moves to restrict access to abortion or to enact pronatalist policies, and the conservative Catholic writer Ross Douthat recently argued that Christianity seems to be window dressing in the administration’s policy rather than a real ideological driver of decision making. Big Tech was a notable boogeyman for the authors, who view smartphones and social media as a danger to traditional religious values, but major Silicon Valley figures have become hugely influential in the White House.

For the Heritage Foundation, Project 2025 has been a somewhat Pyrrhic victory. Although its policy ideas are steering the administration, the think tank finds itself on the outside—a product, it seems, of Trump’s displeasure that coverage of Project 2025 complicated his campaign last year. Heritage is also fighting an intramural battle over how to handle the racist and anti-Semitic strains of the right.

Another, larger question looms. For decades, American conservatives have argued for restraints on government, in part out of fear of how progressives have used power to enact their policies. Project 2025 threw that out, embracing right-wing big government. Its unpopular ideas are one reason that Republicans are facing a daunting election environment in 2026 and perhaps 2028. If Project 2025’s authors felt, as Russell Vought once said, that America was “in the late stages of a complete Marxist takeover” before Trump returned to office, they may find the situation even more apocalyptic if a Democrat wins the presidency in 2028—and inherits the sweeping powers they have handed to the White House.

Related:

Evening Read

All Hail Dead Week, the Best Week of the Year

By Helena Fitzgerald

Christmas is over and we have arrived at the most wonderful time of the year—nominally still the holidays, but also the opposite of a holiday, a blank space stretching between Christmas and New Year’s Eve when nothing makes sense and time loses its meaning …

In between the end of the old year and the beginning of the new one is this weird little stretch of unmarked time. For most people, this week isn’t even a week off from work, but at the same time it also isn’t a return to the normal rhythm of regular life. Nobody knows what to do with this leftover week, awkwardly stuck to the bottom of the year. I call it “Dead Week,” a time when nothing counts, and when nothing is quite real.

Culture Break

Listen. Here are the 10 best albums of 2025, according to our music critic Spencer Kornhaber.

Read. In 2024, Amanda Parrish Morgan recommended six books to read by the fire.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Rafaela Jinich contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

2025-12-29 21:00:00

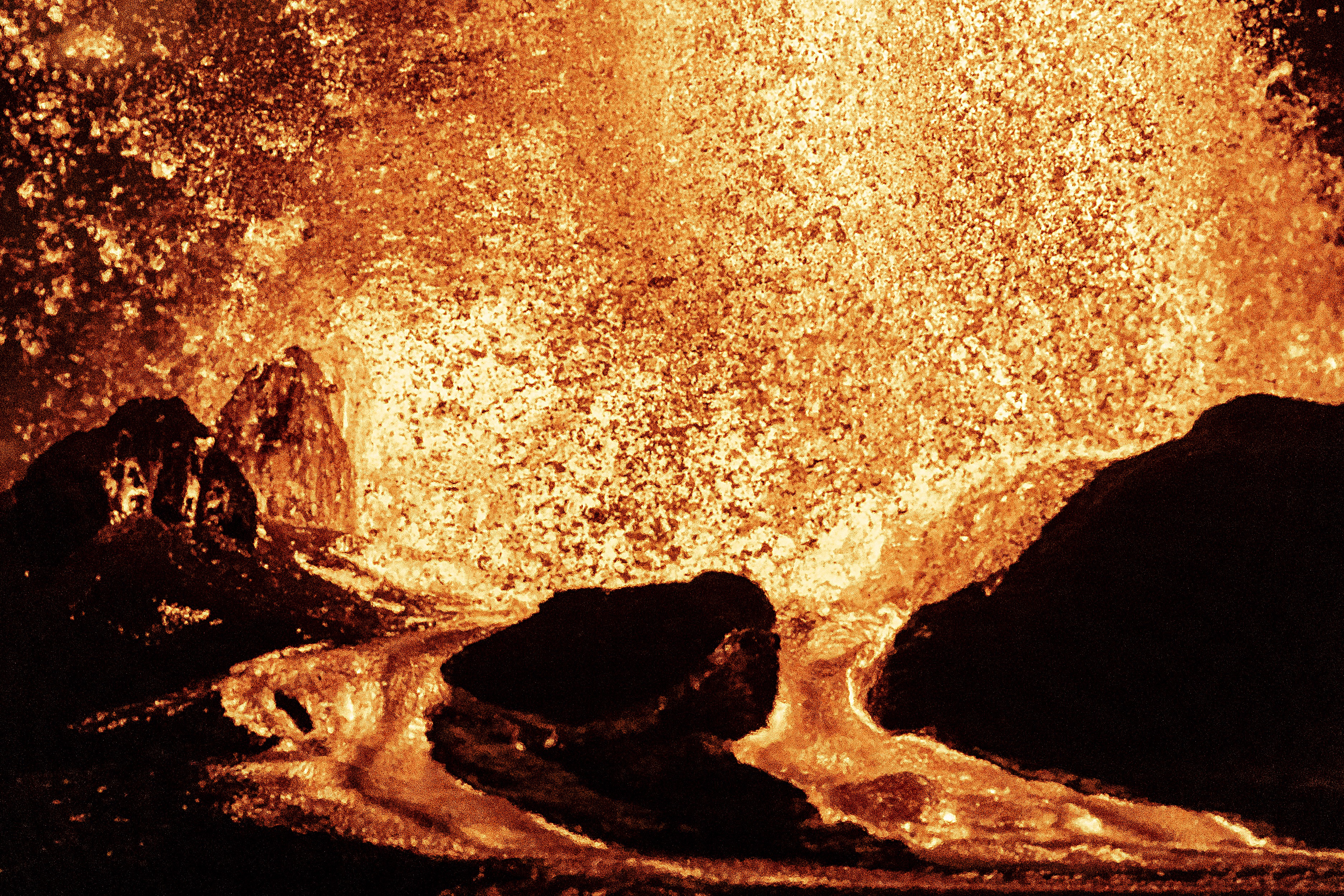

This photo essay originally misidentified the location of Kīlauea volcano.